Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

As the opioid epidemic worsens, people are desperate for natural pain relief options. Wild lettuce has been used for millennia as a natural herbal pain reliever, and now survivalists are touting it as a form of morphine that grows in your backyard.

I’ve seen that catchy, click-bait headline a dozen times at least. “Wild Lettuce Works Like Opium!” Come on, can that possibly be true?

Trust me, I’d be all for a natural herbal pain reliever without nasty side effects or addiction. Nonetheless, I’m skeptical.

How does wild lettuce stand up to modern scientific testing? Time for a little research, and then I’ll try it out myself…for science.

Medicinal Benefits of Wild Lettuce

Let’s start with the basics. What are the supposed medicinal benefits of wild lettuce?

Wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa) is used most commonly as a pain reliever, but it’s also purported to have impacts on specific conditions. It’s said to relax respiratory conditions such as whooping cough and asthma. Wild lettuce has sedative effects that have been used to treat all manner of issues ranging from generalized anxiety and hyperactivity to nymphomania.

It is also sometimes used topically to treat skin conditions and as a wound disinfectant.

Various sources say that it was used by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. Some say it boosted the sex drive, and others say it was used to slow the sex drive. Regardless of the effect on the libido, all three ancient peoples record using wild lettuce as a pain reliever.

A catalog of medicinal plants from 1917 listed wild lettuce as “highly esteemed to quiet coughing and allay nervous irritation, a good safe remedy to produce sleep, to be used when opium and other narcotics are objectionable.” This was at a time when opium and cocaine were widely available and legal, and still, wild lettuce was seen as an effective alternative with fewer side effects.

Is Wild Lettuce Effective?

While it has a long history of use for pain relief, is it actually effective? There are a few modern scientific studies that tried to answer that exact question.

Wild lettuce is native to Iran and used in traditional medicine there.

A study at an Iranian medical center cites that “Lactucarium [wild lettuce sap] is a diuretic, laxative and sedative agent which relieves dyspnoea, and decreases gastrointestinal inflammation and uterus contractions. It has anticonvulsant and hypnotic effects as well. In addition, the lettuce contains traces of hyoscyamine, which is probably responsible for its sedative effects.”

As to its pain-relieving properties, a study in the journal of phytotherapy research found that a compound in wild lettuce known as lactucin has sedative effects in mice at relatively low doses (2mg/kg). In larger doses (15mg/kg), lactucin begins to have significant pain-relieving effects.

Another study confirmed these findings, noting that some pain-relieving effects could be documented at doses of (15 mg/kg). While that dosage produced the first noticeable effects, the active compounds in wild lettuce only became as effective as a standard dose of Ibuprofen at 30 to 60 mg per kg of body weight.

So it appears that extracts from wild lettuce sap actually do have pain-relieving properties! That said, they appear to be relatively mild and not exactly opium strength. All of these studies were done on extracted herbal compounds, and it’s possible that the whole herb has a synergistic effect with multiple compounds, but that hasn’t been specifically studied.

Wild lettuce Dosage

All of the studies investigating wild lettuce for pain relief were conducted using pure isolated lactucin rather than wild lettuce sap itself. One source says that the sap contains 50-60% lactucin, so dosages of sap would be roughly double that of the dosages noted in the studies.

The average adult in the US weighs about 80kg (~180lbs). Theoretically, they’d have to consume at least 30 mg per kg of body weight, or 2400 mg (2.4 g) of wild lettuce sap to experience the effects of ibuprofen. The herbalist Michael Moore estimates that a single 4-foot tall plant should yield about 2-3 grams of dried sap, or about a single dose.

One source suggests a dosage of 1.5 grams of dried sap brewed in a tea, or 0.25 grams of wild lettuce sap smoked in a pipe. The effects are supposed to be much more dramatic when smoked, thus the lower dosage.

It’s possible that the sap itself is more effective than the isolated lactucin compound, but I would imagine you’d still need to consume a good bit to reach opiate-like effects. At that point, you’re obviously risking potential side effects…

Wild Lettuce Side Effects

Though wild lettuce is supposedly safer than opium, it isn’t without side effects. One source lists the side effects as “nausea, vomiting, anxiety and dizziness.”

A medical paper written in 2009 describes the symptoms of 8 patients who had consumed wild lettuce and experienced toxic effects. It was a group of men ages 18-38 who consumed it together, so I doubt their motivations were pain relief.

The study doesn’t have any documentation on how much plant material they consumed, but it does note that they ate it in the wrong season. It was harvested in May, instead of in July/August, which may have impacted its toxicity.

The eight men experienced varied symptoms, including agitation, severe anxiety, blurred vision, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, hyperactivity, euphoria and loss of consciousness. All of them recovered in 1 to 3 days.

Since wild lettuce is getting lots of press as a substitute for opium, it was only a matter of time until someone tried to inject it intravenously. That’s not a traditional preparation, but clearly, that wasn’t a consideration in this case.

The study documents side effects including “fevers, chills, abdominal pain, flank and back pain, neck stiffness, headache, leucocytosis and mild liver function abnormalities.” Nonetheless, the patient recovered fully within 3 days.

At least thus far scientific literature hasn’t had a case where wild lettuce users managed to overdose in a manner that impacted them permanently, but just because it hasn’t happened doesn’t mean it won’t.

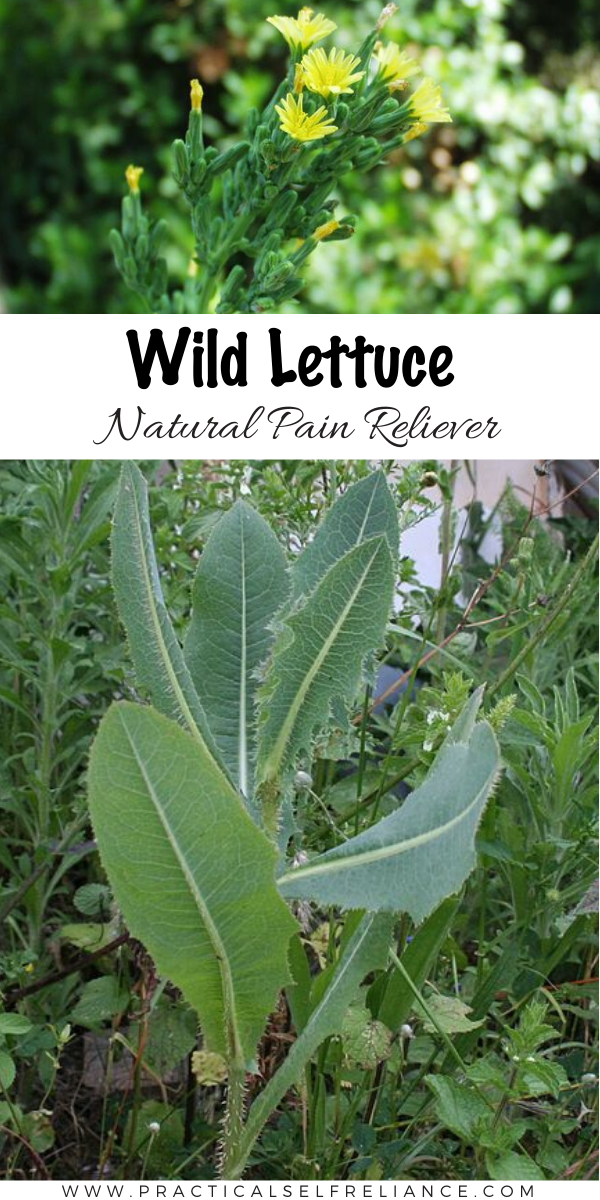

Identifying Wild Lettuce

Identifying wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa) can be a bit tricky, as there are other related species that look quite similar.

Some people think it looks like a dandelion, and while I’d agree that the flowers are yellow, that’s about where the similarity ends. Dandelions produce leaves at the ground level in a rosette and send up flower stalks without leaves. Wild lettuce produces leaves all the way up the stalk, and the flowers aren’t quite the same.

Prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola) on the other hand, is very similar to wild lettuce.

The main difference is in the leaves. Prickly lettuce has less rounded leaves with deep serrations at its edge. The stalk of prickly lettuce is stiffer and a bit woodier, but you’ll only really notice that if you have both plants side by side.

The stalk of real wild lettuce has a texture that’s a bit like the main rib on a romaine leaf. Use your thumbnail to try to puncture the stem and it should be soft and juicy like a romaine rib, though it doesn’t necessarily look anything like cultivated lettuce. The stalk can have a purple tint as well.

Once prickly lettuce and wild lettuce reach the flowering stage, the blossoms are pretty much identical. That leads to more confusion, so keep your eye on the leaves.

If you do accidentally harvest prickly lettuce by mistake it won’t hurt you. In fact, some herbalists say that prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola) and wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa) both have the same effects, but that prickly lettuce is milder.

Others site that prickly lettuce is especially good at relaxing your libido, which is anything but exciting. If you harvest prickly lettuce it may not relieve pain or provide an opiate high, but at least it won’t hurt anything more than your lover’s ego.

To the best of my knowledge, wild lettuce does not have any toxic look-alikes. That said, I’m always amazed at what people will manage to wishfully identify as the medicinal plant they’re hoping to find. Please be sure you’ve positively identified anything you’re wild harvesting, and use your best judgment.

I’ve made a short video comparing wild lettuce to prickly lettuce, and demonstrating the harvest method.

Wild Lettuce Look-Alikes

Besides prickly lettuce, which is also in the Lactuca genus and should also have mild pain-relieving properties, wild lettuce also has other look-alikes. It’s a bit trickier with common names used to describe plants rather than their Latin names.

I’ve heard a few sources that say Sow Thistle and Wild lettuce are look-alikes. There are many plants that go by the common name “sow thistle.” Some with yellow flowers, some with pink, but most look very little like wild lettuce beyond the small spines. We have a “sow thistle” here (more commonly called “Canada Thistle,” Cirsium arvense) that looks nothing like wild lettuce, other than the fact that it has prickles. The flowers are purple (not yellow) and the growth form is completely different.

There is another plant called sow thistle (sonchus sp.) that is also edible and looks almost identical to wild lettuce. There’s a very detailed discussion of this and how to tell them apart in Nature’s Garden by Samuel Thayer and this coming summer I’m going to attempt to take very detailed photos and discuss the differences.

Samuel Thayer notes that sow thistle (sonchus sp.) looks almost identical to wild lettuce except for the spines on the midrib. He then goes on to say that sometimes the spines are almost non-existent or very hard to see depending on whether the plant is growing in sun or shade… making things even more confusing.

Harvesting Wild Lettuce

Wild lettuce is harvested over an extended period of time, by systematically decapitating wild lettuce stalks and bleeding the milky sap.

One modern author describes the process in detail,

“Decapitate 20 three-to-four-foot-tall plants by cutting all the flowers from each. Throw those away. Allow the milky sap to ooze out and dry a bit, then scrape it off into a bowl.

Taking shears in hand, snip another half-inch off the same stalk, allow the sap to bubble out and dry a bit, and scrape it off into a bowl. Continue until the plants are about a foot tall or so.”

Perhaps it’s due to our short summers, but I’ve never seen a wild lettuce plant taller than 2-3 feet. Since they’re starting a good bit shorter, I harvest them all the way down to the ground and get about the same amount of usable material as if I were harvesting a 4-foot plant.

That same author also suggests that since harvesting wild lettuce is a tedious task, that it’s “best conducted in company, like corn shucking, or alone in a manic episode of herbal fanaticism.”

Another author from the ’80s is a bit more colorful in his descriptions, “Figure a yield of 2-3 grams from a four-foot plant after it has been systemically bled until reduced to a one-foot-tall, headless pygmy and the latex dried down in a shady but breezy place until it resembles a mixture of butterscotch pudding, dried library paste, and tubercular phlegm.”

The traditional method used to harvest wild lettuce is tedious and time-consuming, but for good reason. Many modern guides will tell you to skip the traditional harvest methods altogether, opting to quickly chop or pull up the whole plant and stuff it into a blender. If you do that, you’re likely just wasting your time.

There is absolutely no reason to spend an hour carefully and painstakingly extracting wild lettuce sap a drop at a time unless that’s the only way that works. Our ancestors weren’t idiots, and if they could just chop a plant down and have instant opium they would have done it. They may not have known the exact reason for the slow bleed extraction method, but modern science has them covered.

Many plant-based medicines are produced by plants as a response to stress or predation. The tobacco plant is a great example. In a plant physiology course in college, I was surprised to learn that tobacco plants produce dramatically more nicotine when the plants are beaten or cut.

Nicotine is produced within the tissues as a natural pesticide, but it’s costly to make. Tobacco plants wait for signs of predation before producing nicotine in large quantities.

Since tobacco is such a commodity crop, there are numerous studies detailing the exact mechanisms. One such study notes that “after wounding of tobacco plants, roots synthesize a large amount of nicotine to be transported to the shoot.”

Without the injury, followed when a tobacco leaf is injured, it sends a chemical signal to the roots. The roots synthesize the nicotine and send it up to the shoot as a defense. If you just harvest the whole plant in one swift cut, there’s no time for the chemical cascade to happen.

I suspect that there’s a similar mechanism at work in wild lettuce. To test my theory, I started by harvesting a wild lettuce plant using the traditional methodology. That is, I cut it and waited for it to bleed out a glob of sap.

Then I harvested that before cutting it again an inch lower. If you’re really patient and it’s a tall plant the process can take a half an hour or more.

I then harvested a second plant with one cut right at the base. After that harvest, I tried to extract the sap. The first cut, at the top of the plant bled a bit, but the second cut didn’t even yield a single drop.

While quickly cutting down the whole plant may still have some medicinal effect, it seems like a waste. The plant doesn’t have time to synthesize its defense chemicals, and those very chemicals are what you’re after when harvesting wild lettuce.

When to Harvest Wild Lettuce

Gardeners know that domestic lettuce produces a milky sap once it’s gone to seed (bolted). That’s the point it turns bitter and starts putting every last bit of its energy into defending itself from predators as it tries to produce the next generation.

Wild lettuce is no different, and the best time to harvest it is right around the time of flowering. In the northern hemisphere, that happens in July and August.

Up here in Vermont, I saw the first flowers open the last week of July, and the plants will continue to mature in different locations through August. I harvested one plant down to the base early in the season, and about a week later it already has side shoots that are 8 inches high. I expect I may be able to re-harvest from the same plant later this year, hopefully doubling the yield.

Wild lettuce is a biennial, meaning that it flowers at the end of its second year of life. In the first year, the plant focuses on establishing itself and only produces a low-growing rosette of leaves.

The full flower stalk isn’t produced until the second year. Keep that in mind if you identify young plants, or if you’re planning on growing wild lettuce from seed.

Preparing Wild Lettuce for Medicinal Use

So assuming you’ve gone through the painstaking and time-consuming traditional method of harvesting wild lettuce. Even if you’ve done as traditional sources suggest, and harvested from 20 or more plants, you’re still looking at a pitifully small amount of wild lettuce sap. Wild lettuce is thus far completely legal in the United States, to the best of my knowledge, so feel free to experiment responsibly with different preparations to see if they work for you.

How do you prepare wild lettuce sap for use as medicine?

Wild Lettuce Tea

While some blogs will tell you to simply make a tea from wild lettuce leaves, the pain-relieving compounds are not water-soluble (source). Apparently, wild lettuce tea is pleasant tasting, but I can’t imagine that’d be true.

The plant itself tastes horrible, and even the thought of extracting the bitter leaves in boiling water turns my stomach a bit. The fact that wild lettuce tea is unlikely to have pain-relieving compounds present means that I’m not even going to bother with this one.

If you’d like to try wild lettuce as a tea, the dried leaves can be purchased here. If you’d like to try making wild lettuce tea from backyard plants, harvest some of the leaves and then dry them to preserve them for tea.

Wild Lettuce Tincture

While Lactucarium isn’t water-soluble, it is alcohol-soluble. That makes a wild lettuce tincture a great way to use this herb. Assuming the maker of the tincture went through the painstaking harvest protocol and then dissolved the extracted wild lettuce sap in a high-proof alcohol for preservation.

There is one brand sold online that is extremely well-reviewed, and users say that a single dropper full is very effective and begins working after about an hour. The manufacturer recommends 3 doses of a dropper full a day, the final dose at bedtime. Several reviewers mention that they’re using it to successfully manage nerve pain from Lyme disease, which I hadn’t even considered.

While the sap is commonly collected onto a plate of some kind and then dried before being dissolved in alcohol before use, I attempted to harvest the sap directly into a cup of vodka. The sap seemed to readily dissolve right off the plant stem, and hopefully, this skips the tedious drying step. The only risk is that the drying step may volatilize off some part of the plant, or change the medicine in some way.

Wild Lettuce Beer

Since the herbal constituents are alcohol soluble, a medicinal ale is another homemade method to try. The book Sacred and Herbal Healing Beers includes descriptions and a recipe in its section on “psychotropic and highly inebriating beers.”

The recipe includes 1 gallon of water, 12 ounces molasses, 8 ounces brown sugar, 1 ounce prepared wild lettuce sap, and an ale yeast fermented until all activity stops (about 6-8 weeks). The brew is then bottled and bottle aged for 2 weeks before drinking.

The author notes that this beer seems to only affect some people, leading him to believe that the opiate-like effects of wild lettuce may not work for everyone. He also speculates that some of the effects are perhaps related to hopeful drinkers that want to hallucinate.

That said, he believes that given “its long use in indigenous cultures throughout the world for pain relief indicates that it can be reliably used as a feeble opiate for some people. There is some indication that, like many herbs fermented in ales and beers, this opiate-like activity is enhanced during brewing.”

Since this recipe requires prepared Lactucarium, it’s best made with wild lettuce sap that you harvest yourself. In a pinch, you can try making this by adding dried leaves directly to the fermentation vessel as you would dry hop a beer.

Wild lettuce is useful in brewing because it has the same bittering activity as hops, so even if it’s not an opiate it’s still a good wild foraged hops substitute for preserving homemade beer. Any extra pain-relieving properties would just be icing on the cake at that point.

Testing Wild Lettuce

It’s time to take wild lettuce for a test drive. I have no personal history with opioids or any pain reliever of any sort stronger than an over-the-counter ibuprofen. I harvested 2 plants using the traditional method and extracted their sap into 1 ounce of 80-proof vodka.

The taste was better than I expected. Not good, but not nearly as bad as I’d imagined. Quite bitter, and it actually tasted ever so slightly like lettuce.

After about 5 minutes, I was struck by some pretty intense nausea. It lasted roughly 10 minutes, but it was intense enough that it got me worried.

After a round of strong belching, which is not normal for me, the nausea subsided. I do get an upset stomach if I take an Ibuprofen on an empty stomach, and I did have an empty stomach.

Hopefully eating something before trying wild lettuce tincture would prevent nausea. That said, nausea is one of the listed side effects, and if that level of nausea happened every time I’d be pretty disappointed. That said, lacking an over-the-counter pain reliever, I’d probably brave nausea for the pain-relieving effects.

About a half-hour after taking the wild lettuce tincture, I began to feel pain-relieving effects. It also seemed to improve my mood, and I was suddenly both comfortable and laid back.

The effects lasted about 3-4 hours, and I’d estimate it was similar to an over-the-counter ibuprofen or two. The effects were considerably stronger than the willow bark I harvested to use as a herbal aspirin.

Was it opium? Nope. But it was calming and pain-relieving, and definitely worth the effort.

That’s my experience, and I am by no means a doctor or a medical professional. Obviously, use your own best judgment anytime you’re attempting to self-medicate.

There have not been any studies testing drug interactions, so be very careful if you’re on other medications. As with any plant, there’s always the risk of allergy or strange one-off reaction.

Do you have any experience with wild lettuce? I’d love to know about it in the comments below.

I have these plants growing all over my yard. I have used the dried leaves in my medicinal teas but now am going to cut up a large wild lettuce plant that has been drying in my kitchen for 48 hours to reduce the moisture content. Then I will blend the cut pieces in 50% alcohol and store in mason jars, shake every day, and possibly heat to about 140° a few times a week during a tincturing period of 2 to 4 months.

I am too lazy to do all the cooking down jazz, I’m just a chop it up and drown it in alcohol kind of guy. Have had very good luck with all of my other plant tinctures so far.

It would be nice to have a clear recipe with herb & alcohol amounts based on the size of a standard blender.

I always appreciate people who give of themselves helping others with their research etc. I have gleaned a lot of info here. But I have a question about long-term storage. I see you say it (?) can be stored in the fridge for a few days but can it be frozen for long term use or dried to be used later. I don’t have any pain as some of the above folks do but one never knows. Thanks and God Bless You.

You could try freezing it but I don’t know if that will affect how the sap comes out. If you are going to dry it, it’s best to extract the sap and dry just the sap.

A really remarkable blog post. We are really happy for your blog post.