Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Chestnuts (Castanea spp.) are an edible wild nut that’s a real treat to find in the woods. They used to make up a substantial portion of the Eastern Woodland, and now they’re quite rare. The sweet nut meats are calorie rich and well worth the effort when you do find a productive wild chestnut tree.

What are Chestnuts?

Chestnuts (Castanea spp.) are large, perennial, deciduous trees in the Beech or Fagaceae family. Chestnuts are native to the world’s temperate regions. They’re sometimes nicknamed “bread trees.”

There are four main species of Chesnut: the American (Castanea dentata), Japanese (Castanea crenata), Chinese (Castanea mollissima), and European (Castanea sativa). However, there are also a few other species, most of which are referred to as Chinkapins. These trees share many of the Chestnut traits but usually only have one nut inside a bur rather than multiple.

In the United States, the American Chestnut, Allegheny Chinkapin (Castanea pumila), Ozark Chinkapin (Castanea ozarkensis), and Golden Chinkapin (Castanea Chrysophylla) are native. However, people often plant Japanese, Chinese, and European Chestnut cultivars in the U.S..

You may see some American-Chinese hybrids. The American Chestnut Foundation has been working to breed hybrids with the Chinese Chestnut’s resistance to Chestnut Blight, a disease that wiped out most American Chestnut populations. The Foundation has begun distributing blight-resistant hybrids that are 90% American chestnut and 10% Chinese chestnut.

Are Chestnuts Edible?

Chestnuts are edible, and some argue that they are one of the most important trees in human history. They have been a valuable food source for thousands of years, and humans have spread them wherever they grow.

You can eat the nuts raw, but people generally roast them to improve their flavor and remove some of their tannins. As they contain tannins, large quantities of raw chestnuts may cause nausea or indigestion. Raw chestnuts may also be troublesome for people with liver or kidney problems. Baking or boiling the chestnuts fixes this issue.

Herbalists have also used the nuts, nut shells, leaves, flowers, buds, twigs, and bark of Chestnut trees medicinally for internal and external applications.

It is possible to have a Chestnut allergy, so you may want to eat a small amount if you have never tried them before or have other allergies. Interestingly, Chestnuts don’t contain the same proteins that people with peanut or tree nut allergies react to. It’s possible to be allergic to peanuts and other tree nuts and not allergic to chestnuts and vice versa.

In Italy, they have been ground into chestnut flour and used as a wheat flour substitute since the time of the Romans.

Chestnut Medicinal Benefits

One of the easiest ways to reap the health benefits of chestnuts is to eat them. Chestnuts are a good source of fiber and essential vitamins and minerals like copper, manganese, vitamin B6, vitamin C, thiamine, folate, riboflavin, and potassium. They’re also lower in fat than other nuts. The leaves are also high in vitamin K and tannis.

The Chestnut’s use in medicine dates back thousands of years, and herbalists use the leaves, nuts, bark, and flowers. Greek father of pharmacology Dioscourides and Roman physician and medical researcher Galen included Chestnut in their writings.

Historically, herbalists often used the leaves as a tea to treat sore throats, colds, and respiratory ailments like whooping cough. They also used infusions of the leaves and bark to treat arthritis and swelling and to kill bacteria. Herbalists also used Chestnut flower teas to treat sinusitis.

Much of the tree is astringent, and herbalists have used this property to treat diarrhea, bleeding, and wounds. Folk traditions worldwide have also reported using the nuts to treat various ailments, including sores, infections, kidney problems, nausea, bloody stools, and muscle pain.

Native Americans also used the tree medicinally. John Smith of the Jamestown colony reported that local Native Americans made tea from the leaves of the Allegheny Chinkapin to relieve headaches and fever.

In traditional Korean medicine, chestnut inner shell extract is often used to treat lung issues such as asthma, COPD, and pulmonary fibrosis. In 2023, researchers tested this extract against a type of emphysema caused by cigarette smoke. They found that the extract helped to fight the infection and decreased the size of lung lesions. Researchers concluded that his extract has the potential to help alleviate COPD.

Chesnut products may also be effective against swelling and some infections. A 2014 study found that Chestnut buds are a rich source of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds, making them a good choice for natural health products.

One specific infection researchers are using Chestnut on is a gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus. This bacteria causes Staph infections on the skin and respiratory tract. In 2021, a team of researchers looked at treating these skin infections with Chestnut leaf extract based on a traditional herbal practice in the Mediterranean. They found that the extract was effective at inhibiting the Staphylococcus aureus. They also noted that, unlike some other modern treatments, the extract didn’t damage the skin, even in elderly patients.

Chestnut’s antioxidant properties may also protect heart health. A 2012 study found that Chestnut bark extract helped reduce damage from oxidative stress in heart cells. Researchers concluded that the Chestnut extract may be a helpful heart health supplement.

Where to Find Chestnuts

Chestnuts are native to the world’s temperate regions, including parts of North America, Asia, and Europe. For several species, their original native range is difficult to determine, partially because they have spread naturally for millennia and partially because humans have spread them wherever they could. The Chestnuts the Romans planted along Hadrian’s Wall is an excellent example of this!

Originally, the American Chestnut was one of the dominant trees in the eastern forests, found on the mountains, slopes, and rocky, well-draining soils of the Appalachian mountains. Today, it has been almost eliminated by the Chestnut Blight.

The Chinkapins native to the United States include the Allegheny Chinkapin of the Southeast, the Ozark Chinkapin of the southeastern and midwestern United States, and the Golden Chinkapin of the Pacific Northwest.

You may also find the Chinese, Japanese, and European Chestnuts growing in the United States today. These two species are common choices for Chestnut orchards and ornamental plantings.

Usually, you’ll find Chestnuts growing in well-drained, fertile, acidic soil. They’re generally quite drought-tolerant once established. Chestnuts need full sun for good nut production, though you can find them growing in partial shade.

When to Find Chestnuts

Chestnuts are more challenging to identify in the winter, but the advantageous herbalist may identify and harvest Chestnut bark and twigs year-round. The leaves begin to appear in spring. Chestnuts often flower between June and July, with trees growing in northern regions or at high elevations flowering later than those in warmer climates.

Most Chestnut nuts ripen in the fall between September and October. Thankfully, you don’t have to climb these towering tries to reap your harvest; when Chestnuts mature, they naturally fall from the tree. At this time of year, spotting the spiky casings lying beneath productive trees is often easy.

Identifying Chestnuts

Chestnuts vary significantly with species. The four main types of Chestnut trees are all large, stately trees. The species referred to as Chinkapins and a few other Chestnuts, like Seguin’s Chestnut (Castanea seguinii), tend to be smaller trees or large shrubs.

Some species, like the Chinese and Japanese Chestnuts, tend to have multiple leading stems and a spreading nature. Other species, like the American and European Chestnuts, tend to have one massive trunk with a broad, dense crown.

Despite their differences, all of the species share their beautiful, toothed-edged leaves and inconspicuous, wind-pollinated flowers that form in catkins. The Chestnut’s distinctive, spiny fruit is also hard to miss, especially when it falls to the ground in the autumn.

Chestnut Leaves

All of the Chestnut species have simple, alternate, ovate, or lanceolate leaves. The leaves are usually 3.5 to 12 inches long and 1.5 to 4 inches wide, depending on the species and tree.

The leaves are green with widely spaced, sharply pointed teeth along the margins. Between the teeth are rounded sinuates or divisions. This patterning gives the leaf margins a wave-like pattern.

In many species, the leaves turn a golden yellow in the fall.

Chestnut Tree Trunks

As mentioned above, Chestnut species can vary significantly in height, with some being enormous trees while others are more like large shrubs. The Allegheny Chinkapin may only grow 6 to 30 feet tall, while prior to the devastation of the Chestnut Blight, American Chestnuts were known to reach 200 feet tall or greater. The other three main Chestnut species usually range from 30 to 115 feet tall.

Young Chestnuts usually have smooth gray or brown bark, sometimes with noticeable lenticels or pores.

As the trees grow, the bark develops deep fissures and ridges that run up and down the bark.

Sometimes, these form a diamond-like pattern, and sometimes, they twist around the tree as it grows, making the tree appear almost like a large twisted piece of cable or cordage.

Chestnut Flowers

Chestnuts flower in June or July after they have fully leafed out. The flowers form in wind-pollinated catkins, and each tree carries two types: male and female catkins.

The male catkins mature first. They are usually white, pale buff, or yellowish and produce a sweet odor, which some people find unpleasant. They may be up to 8 inches long.

The female catkins are green burs that form on the same twigs. These female catkins develop into fruit if pollinated.

Chestnut Fruit

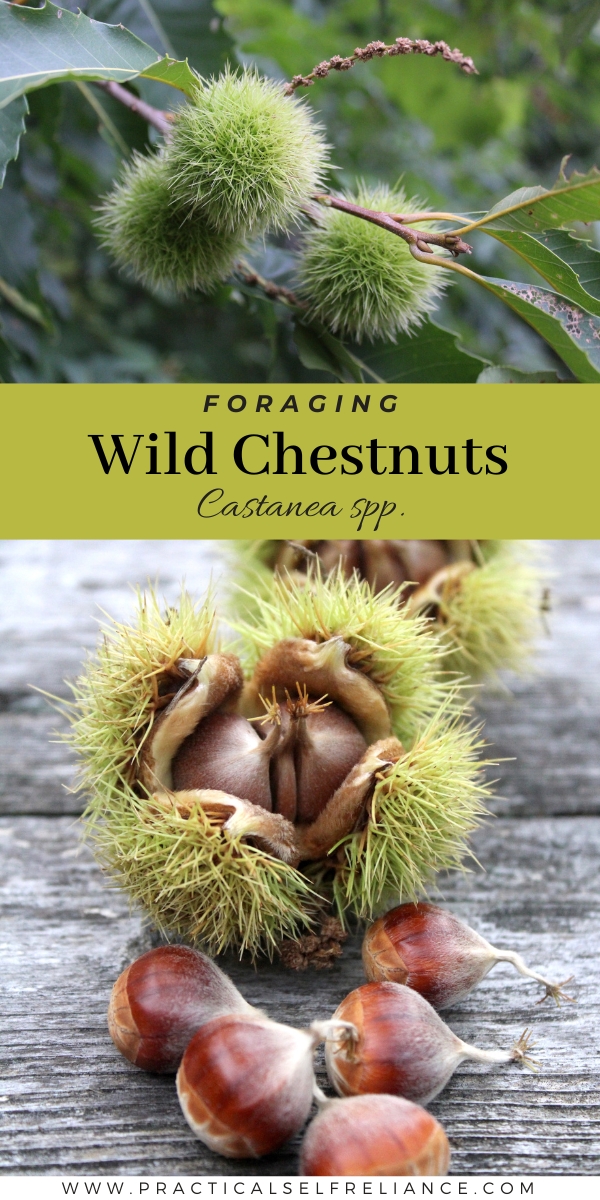

Female Chestnut Catkins form a spine-covered fruit usually called a bur or burr. These burrs look a bit like oversized versions of the burdock burs that you may have gotten stuck to your clothing. Chesnut burrs are very sharp to the touch and are usually about 1 to 4 inches in diameter, depending on the species.

Thankfully for foragers, when the burrs mature, they turn from green to a golden brown, and they usually fall from the tree and then split open in two or three sections. Inside these burrs are one to seven tasty brown nuts depending on the species. The chestnuts may be golden brown, brown, dark brown, or almost black, depending on the species. Usually, the species with multiple nuts are flattened on one side.

All of the Chestnut nuts have a small tassel tip and a hilum or pale brown attachment scar on the other end. Each nut has two layers of skin or peel and then an inside of creamy white flesh.

Chestnut Look-Alikes

Chestnuts are often confused with an unrelated species, sometimes called Horse Chestnuts or Buckeyes (Aesculus spp.). These are toxic unless specially processed. Thankfully, they differ in several ways:

- Buckeyes have opposite, palmately compound leaves.

- Buckeye flowers form in panicles and are showy and bird or insect-pollinated.

- Buckeye fruits are fleshy and may be smooth or have some bumps and spines, but they lack the hedgehog or porcupine-like appearance of true Chestnut fruit.

- Buckeye’s brown nuts look similar to true chestnuts but lack the pointed tassel on the tip.

Chestnuts are also easy to mistake for Chestnut Oaks (Quercus montana). However, there are a few ways to tell them apart:

- Chestnut Oak leaves appear similar at first glance, but the teeth on the leaf margins are rounded rather than pointy.

- Chestnut Oak bark is gray and forms broad, scaly ridges as it matures.

- Chestnut Oaks produce flowers in hairy catkins in the spring, typically in May, before the leaves are fully developed.

- Chestnut Oaks produce acorns similar to other oak species.

Lastly, Chestnuts may be confused with American Beech (Fagus grandifolia). There are a few simple ways to tell them apart:

- American Beech has distinctive, long, thin, cigar-like buds.

- American Beech has elliptical leaves with small, widely spaced teeth along the margins, with each leaf vein terminating in a tooth.

- American Beech leaves are typically broader and shorter than Chestnut leaves and usually only reach 4 ¾ inches long.

- American Beech has smooth silver-gray bark.

- American Beech fruits are much smaller than Chestnuts and are generally less than 1 inch in diameter.

- American Beech nuts are tiny and lack the pale hilum and pointed tassel found on Chestnuts.

Ways to Use Chestnuts

While you can eat them raw, cooking your chestnuts before using them is best. To cook them, first, make a slice in the skin. This slice lets out steam and prevents them from exploding! Traditionally, when cooking over an open fire, some folks liked to keep one chestnut intact. When the unsliced chestnut exploded, they would know the others were ready.

After you slice your chestnuts, you can boil or roast them in the oven, usually between 375 and 425°F degrees. You’ll know they’re ready when the slices you made in them split open. Then, you can peal your chestnuts as soon as they’re cool enough to handle. The hotter they are, the easier it will be to remove the bitter, papery inner skin.

They also roast well outdoors on a grill.

Chestnuts are much more starchy than other nuts but still provide a delightful, earthy, nutty flavor. They’re well suited to starchy savory dishes like stuffing, rice and pasta dishes, stews, or a side dish on their own. They also work well in sweet dishes, especially when paired with other flavorful ingredients like dark chocolate, coffee, and orange.

Medicinally, most of the tree can be helpful. Herbalists have used the bark, leaves, flowers, twigs, and buds in internal and external preparations. Their tannins may help reduce inflammation, fight infections, and kill bacteria. You can experiment using different parts of the tree in teas and tinctures. Including more chestnuts in your diet can also help with digestive issues and they are a valuable source of vitamins and minerals.

Chestnuts Recipes

- Learn the basics of roasting chestnuts with this simple guide from BBC Good Food.

- Create homemade chestnut flour for baked goods, as these were commonly used historically. Chestnut flour is still popular in Italian kitchens today!

- Try a fun, foraged take on the classic shepherd’s pie with this recipe for Wild Mushroom Shepherd’s Pie with Potato-Chestnut Topping from Star chef Grant Achatz at Food & Wine.

- Take your pasta night up a level with this Chestnut Ravioli with Brown Butter Sage Sauce from Italian Food Forever.

- Make a hearty winter side or vegetarian main with this recipe from Olive Magazine for Gem Squash with Cranberry and Chestnut Stuffing.

- Try this recipe for 3-Ingredient Chestnut Puree with Whipped Coconut Cream from Heartful Table for a simple dessert that lets the chestnut’s flavor shine.

- Be sure to save some of your chestnuts for celebrating the winter solstice! In some German and Baltic folklore, a witch named Lutzelfrau hands out sweets, fruits, and nuts, especially chestnuts, on St. Lucia’s Day. Have fun with this old chestnut lore with these luscious Lutzelfrau Dark Chocolate Tarts from Gather Victoria.

Wild Nut Foraging Guides

Looking for more edible wild nuts to forage this Autumn?

- Foraging Black Walnuts

- Foraging Butternuts (White Walnuts)

- Foraging Beechnuts

- Foraging Shagbark Hickory