Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

There’s a theory that the tastiest things need the best defenses. If you’ve ever stepped on or brushed by a bull thistle, you’ve experienced their robust defense system. What on earth are they hiding behind all of those thorns?

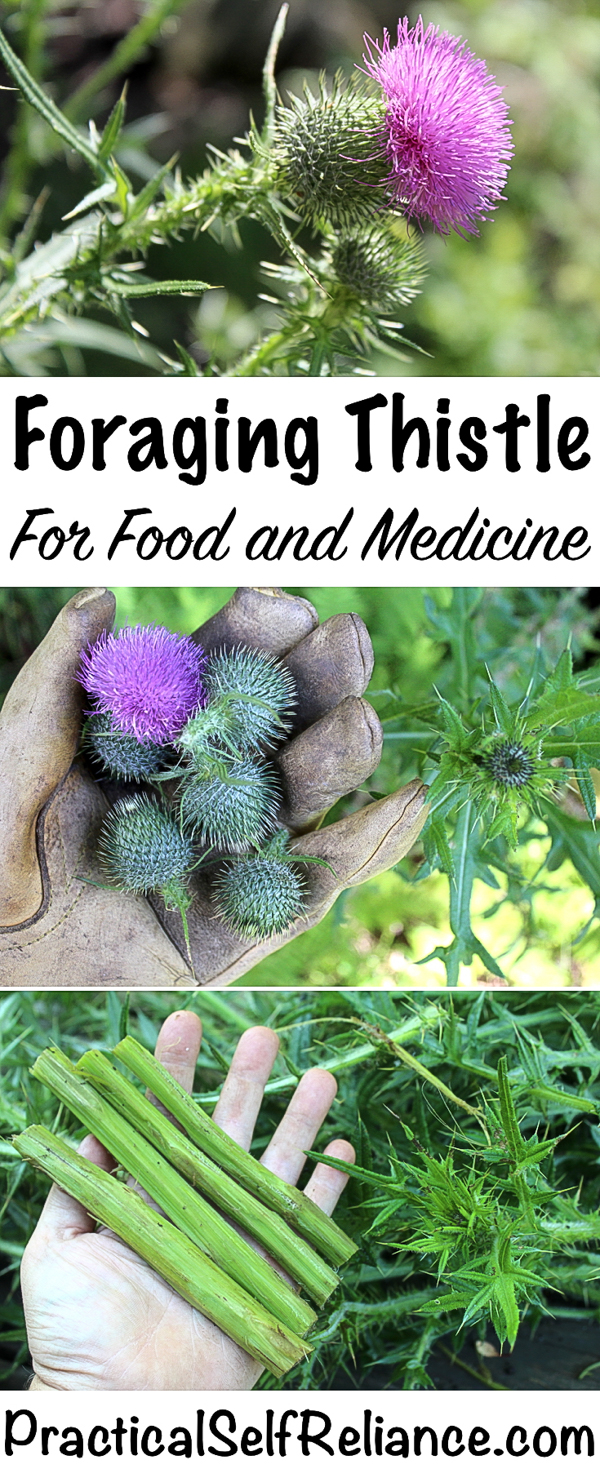

A bit of research reveals that every part of thistle is edible so long as you can get past the thorns. It’s time to put that theory to the test and see how thistle tastes.

Around here it’s not too hard to find a thistle plant, and our main variety is common Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare). The seeds are wind-dispersed, and they’re liable to pop up in any corner of our land that gets decent sun. This thistle plant I’m testing is a bull thistle, and the spines are huge and rigid.

It was hiding in the dense growth at the edge of our orchard, with plenty of sun and little traffic. Given the opportunity, a bull thistle can grow to 5 feet tall, and send out multiple flower stalks.

I didn’t notice it getting quite so large until I walked by in shorts…

Thistle Root

Thistles will resprout readily if cut down, so it’s best to dig the whole plant up by the root. The root is edible, and according to one source, it tastes “like burdock root only better.”

While burdock stalks are delicious, I really can’t stand burdock root, and I think it tastes like bitter dirt. Thus, I’m not excited about cooking up a thistle root. But still, I have to know.

I chopped off the root, cleaned it up and found out that it does indeed taste just like burdock root. Not quite as much like dirt, and not quite as bitter, so I guess the description like burdock only better fits.

There’s a reason all the burdock root I harvest ends up in burdock tincture, rather than my stew pot. My verdict…technically edible, and good to know about, but nothing I’m planning on eating short of the apocalypse.

Thistle Leaves

Next up is the thistle leaves. To eat thistle leaves, all the spines need to be removed. Take a look at those spikes, most of them are about 1 cm long and surprisingly rigid. They’re quite thin, so you’d think they’d be weak and flexible, but not exactly.

Foraging books warn that you should use extreme caution when harvesting bull thistle because it can cause permanent damage to the cornea if it comes in contact with your eye. The only other plant I’ve seen such a stringent warning on regarding eye protection is hawthorn, and the thistle spines are almost as nasty. Watch out for that one, and seriously consider eye protection.

Even wearing leather gloves I managed to puncture my thumb five separate times, through the glove. It was always the same thumb, so clearly I was repeatedly grabbing it the wrong way?

The spine stuck in my thumb and stayed there so it could only be removed by removing my glove. No fun, I promise.

I tried cutting off just the individual spines to leave more of the green leafy material, but there are so many small spines along the leaf that I just kept cutting and cutting, leaving very little leaf material in the end. Practically speaking, that means the only thing left is the mid-rib in the center of the leaf.

The mid-rib is quite long on most leaves, and thick towards the base. It tasted like a mildly sweet and reasonably pleasant celery. Still, that was a lot of work for celery. After all those spines I would have hoped for something at least as nice as a sugar pea, but no luck.

Thistle Stalk

Now onto the central stalk. To get to the stalk, you have to remove all the thistle leaves. Since many of the leaves are over a foot long, I was wishing for longer gloves as I reached in to cut the leaves off with my knife.

I tried grabbing the leaves and pulling them off with gloved hands, but the spines went through my gloves a couple of times and I went back to my knife. In the end, I had a long stalk, still with a lot of spines, and a huge pile of thistle leaves.

The next step, and definitely the easiest part of this whole spiky adventure was skinning the thistle stalk.

That’s not the say it’s not spikey, look at those monsters…

Still, by pinning the stalk down at one end and then running a pocket knife along its length, the whole thing was skinned in seconds. I chopped the stalk into several shorter pieces to make it a bit more manageable, and so that it’d fit into a pot.

The stalks are quite tough, and they remained tough even after simmering in boiling water. The taste was again, a bit like celery. This time, they weren’t quite as pleasant as the leaf midribs, and there was a good bit of bitterness. I can imagine they’d add flavor and crunch to a soup if simmered long enough.

As I chopped the stalk into pieces, it bled a milky sap and it took quite a bit of pressure to get my knife through the tough stem.

I started to wonder if maybe I’d harvested it a bit too late. Perhaps it would be less bitter harvested earlier, but the yield would also be much lower.

Thistle Blossom

The last part of the thistle remaining is the flower. The thistle I originally harvested hadn’t bloomed yet, so I waited a few more weeks and found another thistle in full bloom.

It took a bit of patience because the blossoms were almost continuously covered in bees. Clearly, they’re enjoying them.

With patience, I was able to harvest a handful, and they’re actually much less spiky than the rest of the plant. I brought gloves and used the gloves to pull them off, but cutting them with gloved hands was tricky. I quickly found that the spines on the thistle blossoms aren’t nearly as sharp as those on the leaves and stalk.

I, of course, misremembered what I’d read about eating thistle flowers. I thought I had to wait until they bloomed, but once I got inside I checked again. In A Forager’s Harvest, one of my favorite foraging books, Samuel Thayer says that,

“The globe artichoke is the giant flower bud of a plant very closely related to wild thistles. It is possible (although not necessarily pleasant) to peel the bristly bracts from the outside of the thistle flower bud (well before flowering time) and expose a tiny, tender, delicious artichoke-like heart. Unfortunately, this vegetable is less than half an inch in diameter – so small that it is hardly worth mentioning except as a curiosity.”

Peeling the thistle flowers proved difficult, but I cut the smallest one I had in half and exposed something that vaguely resembled an artichoke. Still, it is about an inch in diameter, and much larger and more developed than what Samuel Thayer described. Given how much trouble I had peeling the larger version, I’d agree that it may be interesting as a curiosity, but not practical.

I’m pretty open-minded when it comes to foraging, but all in all, I’d say thistle really isn’t worth the effort except in an extreme survival situation. Even still, I’d need to have gloves on hand, and I’d guess I used up way more calories processing thistle into food than it contained.

Medicinal Uses of Bull Thistle

Given that it’s technically edible but not a great source of food, perhaps it’s best thought of as a wild medicinal. It’s been used for generations by Native American peoples, and while researching the medicinal uses I found a bit more insight into why someone might go through the effort of skinning out a leaf mid-rib.

The juicy leaf mid-ribs were used as a clean water source! They are wet, and though not spectacularly tasty, they are wet. Since water’s not exactly limited here in Vermont it hadn’t occurred to me.

Beyond its use as a water source, thistle is well known for its ability to treat swelling of joints and tendons. I was pretty impressed by reading a paper by the American Herbalists Guild that describes its use for joint issues, such as rheumatoid arthritis, especially in children. It’s also been used to treat other inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel syndrome.

The case study describes multiple cases where patients were not able to stand due to joint pain but were able to regain function after drinking a tea made from the leafy parts of bull thistle several times per day. That’s exciting and worth knowing as a potent anti-inflammatory. Still, my go-to wild foraged anti-inflammatory is wild lettuce, and though it’s also spikey, it’s much easier to handle and just as common.

I really enjoyed reading everything that you wrote about the thistle including all of the details and photos.

Everything you’ve heard was filled with interest and good knowledge.

Thank you for taking your time to share this great story and experience along with the pros and cons.

You’re quite welcome. I’m glad it was helpful to you!

Interesting post. As you said, good to know in post-apocalyptic times! Prior to that, it would seem there are better alternatives for most of the uses listed, especially considering the difficulties with foraging and preparation. Still, I have, (while not of Scottish descent), an affinity for all things Scottish and am only too happy to enjoy the sight of thistles in bloom without partaking in their culinary and medicinal joys! Thanks for the info though.

I have since heard that many people really enjoy the cooked roots, and say they’re the best part, peeled and cooked like parsnips. Beyond that, this year we made a flower jelly out of the blossoms and it was mild and tasty, surprisingly similar to apple blossom jelly or clover jelly.

Just sharing the new valid link for the article, so you can update!

https://americanherbalistsguild.com/herbal-breakthrough-rheumatology-bull-thistle-cirsium-vulgare-spondyloarthropathy/

Thanks so much! I’ve updated the article.

Great article! I found that welding gauntlets are effectively protective when dealing with thistles!

That’s great! Thanks for sharing.

How do you process them to keep? I just dug up over a dozen thistles and I don’t want them to go to waste!

What did you end up doing with your thistle?

The stalk is much more tender (can be eaten raw) and has a better flavor if it’s harvested well before the flowers appear. Excellent added to tuna or egg or potato salad. Nice to see someone else in VT is enjoying the wild edibles!

In Iran, Spear thistle is eaten with yogurt or used in stews (usually with beef chunks) served with rice.