Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

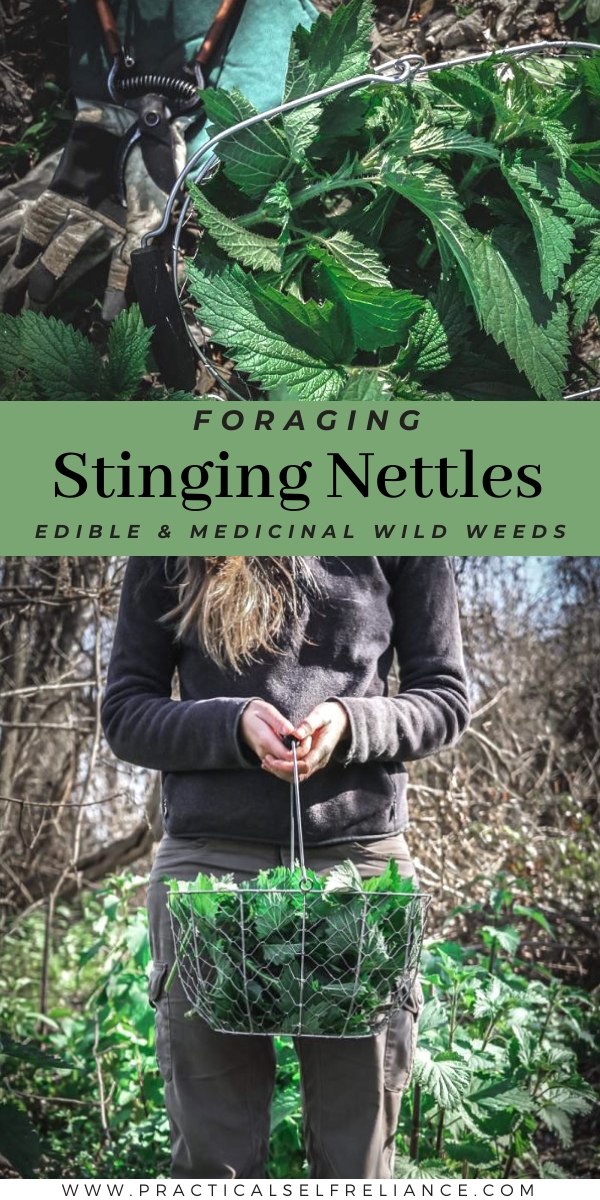

Foraging stinging nettles can be a bit intimidating, they sting after all! When harvested with care, stinging nettles are easy to forage and well worth the effort.

Learn when and where to find this wild food, how to identify, how to prepare, and how to avoid the sting!

Stinging nettles can be tricky to forage, but it can be done while avoiding the sting. Use gloves and harvest carefully, and you can go home with these delicious edible and medicinal wild weeds.

A quick cook in boiling water de-activates the sting, and you can use them however you please!

What is Sting Nettle?

Stinging Nettle (Urtica Diocia) is an herbaceous, perennial plant in the nettle or Urticaceae family.

Stinging Nettle has several common names, including Burning Nettle, Burn Nettle, Common Nettle, or just Nettle. It’s native to parts of Europe, Asia, and North Africa but has naturalized worldwide.

Is Stinging Nettle Edible?

Don’t let the name scare you off! Stinging Nettles are edible and highly nutritious plants. You can eat stems, leaves, and seeds.

As their name suggests, Stinging Nettles are covered in fine hairs that are irritating to human skin. However, it’s quite easy to harvest and process them without being stung to enjoy their flavor and benefits.

When gathering Stinging Nettles, you may want to wear gloves. This will make it simple to harvest them without contacting the hairs. However, many foragers choose to forgo gloves, especially if they find a good patch of nettles on an unrelated outing.

Folks with tough or calloused fingers and palms may discover they can touch the plants with these parts of their hand without getting stung. Just be careful to avoid brushing the sensitive skin on your wrists and arms against the nettles. The hairs on the stems generally lean upward, so if you pick the stem by moving your fingers with the grain of the hairs, you’re less likely to be stung.

If you do get stung, don’t worry. The irritation is relatively minor and doesn’t last long. Applying a poultice of Jewelweed can help soothe your skin.

You also need to process the leaves and stems by blanching them quickly in hot water or drying them to remove the histamines and other chemicals that would normally be irritating from their hairs. You can eat the seeds raw.

Stinging Nettles are generally the tastiest when they’re young and small. As the plant grows, the stems and leaves become tougher and more fibrous. However, you can still use older plants for tea.

That said, you should harvest nettle leaves and stems before the plant has flowered. After flowering and as the plant begins forming seeds, gritty particles called cystoliths begin to build up in the leaves and stems. Cystoliths can be irritating to the kidneys and urinary tract. However, cystoliths can be broken down by acid, so you can use more mature nettles if you ferment them.

As with other wild edibles, be sure to harvest your Stinging Nettle in areas that are free from pollution. Avoid sites that may be contaminated with toxins or pesticides from roadsides or runoff.

Stinging Nettle Medicinal Benefits

Among herbal enthusiasts, Stinging Nettle is known for being part of the Nigon Wyrta Galdor or Nine Herbs Charm. The charm was part of a manuscript written in the 9th or early 10th century called Lacnunga, which is Old English for ‘remedies.’ It’s a ‘healing spell’ or ‘galdor’ in Old English.

Stinging Nettle is still a widely used herb today. Herbalists employ Stinging Nettle to treat allergies, UTIs, kidney stones, anemia, prostate issues, gout, and more. Stinging Nettle is also believed to be a galactagogue or herb that promotes location. A clinical study completed in 2018 found that mothers who drank an herbal tea containing Stinging Nettle saw an increase in milk production after seven days.

Stinging Nettles are also high in vitamins and minerals and are often used as a spring tonic. They have high levels of vitamins C and A, calcium, potassium, magnesium, zinc, and iron. Some sources claim they have the highest protein levels of any green vegetable, and one study found that powdered Stinging Nettle leaves were 33.8% crude protein.

Though not widely used today, urtication or intentionally contacting the skin with nettles to cause inflammation was a common folk remedy. Urtication was believed to help with rheumatism, paralysis, gout, and other musculoskeletal pain. It was first recorded as a treatment for paralysis by a Roman naturalist, Pliny the Elder.

Where to Find Stinging Nettle

Stinging Nettles are native to parts of Europe, Asia, and North Africa but have naturized throughout much of North America. They’re fairly widespread and common except in dry regions, the far north, and high mountainous areas.

Stinging Nettles thrive in openings with full sun and moist, fertile soil. You can often find them growing in forest openings along the banks of streams, rivers, and lakes. You may also spot it in disturbed habitats like ditches, fencerows, woodland edges, low pastures, fields, and waste areas if the soil has enough nitrogen and moisture.

When to Find Sting Nettle

In most of the United States, Stinging Nettle can typically be found from early spring to late summer or fall. In milder climates, you may find Stinging Nettles as early as March and as late as September. The best time to harvest Stinging Nettles is in early spring when they’re small and tender.

The plants will die back in the fall, but they will return from their rhizomes in the spring. They will also spread by seed, and the seeds germinate in the cool weather of early spring.

Identifying Stinging Nettle

You’ll typically find Stinging Nettles growing in large, dense patches. They spread by seed and underground rhizomes and form colonies. They grow straight and tall and can be quickly recognized by their stinging hairs.

Stinging Nettle Leaves

Stinging Nettle leaves are ovate or lanceolate with pointed tips, coarsely toothed, and usually have a heart-shaped base. They are soft, hairy, and green with depressed veins that give them a rough or almost crinkled appearance.

The leaves grow to about 2.5 inches in length and are attached to the stem by petioles. The petioles may be up to 2.5 inches long and generally get shorter toward the top of the plant.

Stinging Nettle Stems

Stinging Nettle stems can reach 5 to 8 feet tall at maturity. They rarely exceed 0.4 inches in diameter and are typically green and hairy. The stems are squarish, hollow, and have four deep grooves running down them.

Stinging Nettle stems are surprisingly tough, especially when mature, because of their strong fibers, which become apparent if you try to tear one. The stems rarely branch.

Stinging Nettle Flowers

Stinging Nettle has numerous, tiny, inconspicuous flowers that are greenish or brownish in color. The flowers are borne on densely packed inflorescences up to 3 inches long. The inflorescences grow from the leaf axils or between the leaf and stem.

Stinging Nettle Fruit

The flowers give way to small, hairy green fruits that are densely packed along the inflorescence. The seeds aren’t readily visible unless you look closely; they’re hidden in the remains of the flowering parts.

Stinging Nettle Rhizomes

Stinging Nettles’ most reliable method of reproduction is through underground, creeping rhizomes. The rhizomes grow with the plant’s fibrous roots to about 6 inches deep and are yellow or whitish in color. They can spread 5 feet or more in a single season. Rhizome sections sometimes get caught in agricultural equipment and form new colonies where they are dropped.

Stinging Nettles Look-Alikes

Stinging Nettle is often mistaken for Wood Nettle (Laportea canadensis), another tasty wild edible with a similar sting. You can differentiate them in the following ways:

- Wood Nettle thrives in shade or partial shade rather than full sun.

- Wood Nettle typically has less than 12 leaves on a mature plant.

- Wood Nettle leaves are ovate and alternate.

- The young stems of Wood Nettle are round, solid, and tapered.

- Wood Nettle seeds are dark brown, flattened, and resemble small flax seeds.

- Wood Nettle grows to 3 to 5 feet tall.

- Wood Nettle has male and female flowers, and the female flowers form in large, flat clusters at the top of the plant.

Stinging Nettle may also be confused with White Dead Nettle (Lamium album). However, it can easily be differentiated in the following ways:

- White Dead Nettle leaves are covered in soft hairs.

- White Dead Nettle has individual white flowers which form in whorls on the upper part of the stem.

- White Dead Nettle rarely exceeds 39 inches in height.

- The plant lacks any stinging hairs.

Another Stinging Nettle lookalike is Clearweed (Pilea Pumila). It can be distinguished from Stinging Nettle in the following ways:

- Clearweed typically grows in the forest in wet areas with partial to full shade.

- Clearweed typically only grows to about 28 inches tall.

- Clearweed leaves are bright green and shiny.

- The plant lacks any stinging hairs.

Stinging Nettle is also mistaken for False Nettle (Boehmeria Cylindrica). Fortunately, it too differs in a few easy-to-spot ways:

- Also called “Bog Hemp,” False Nettle is typically found growing in wet areas like ditches, bogs, swamps, streambanks, and wet meadows.

- False Nettle has a smooth stem that may be branched.

- False Nettle leaves are broadly oval-shaped, smooth, and hairless.

- The plant lacks any stinging hairs.

Lastly, Stinging Nettle is often confused with a closely related and also edible nettle, Dwarf nettle (Urtica urens).

- As the name suggests, Dwarf Nettle is smaller and doesn’t typically surpass 30 inches in height.

- Dwarf Nettle leaves are more elliptical and deeply toothed, and the terminal tooth is the same size as the marginal teeth.

Ways to Use Stinging Nettle

Widespread and often readily available, Stinging Nettles are an excellent herb to know how to gather and use for both culinary and medicinal purposes.

Harvest Stinging Nettles and blanch them in boiling water for a quick, highly nutritious side to any meal. After blanching, you can also use them in place of other greens like spinach or chard in other dishes, including pasta, rice, and soups. The seeds are also edible and you can add them to granola, breads, and other baked goods.

Stinging Nettles also make a healthy, hearty tea that’s often best with a little honey or maple syrup. The tea is high in vitamins, including C and A, and is believed to help with various issues, including helping to increase milk supply in nursing women.

If you harvest more than you can use fresh, drying Stinging Nettles is a great way to preserve them. Dehydrating Stinging Nettles removes the “sting” and allows you to use them later in teas or cooked dishes. You can also powder the dried plants and use the powder to help thicken and add protein soups, stews, and other dishes.

The strong fibers of Stinging Nettles also lend the plants to the crafting of cordage and textiles. During World War I, Stinging Nettles became the base fiber of German and Austrian military uniforms due to wartime shortages of other textiles.

Stinging Nettles also create an excellent natural green dye. During World War II, England used about 90 tons of dried Stinging Nettles to create green dye for camouflage.

Stinging Nettle Recipes

- Bake something truly whimsical with this Nettle Cake from The Wondersmith.

- Create your own nettle beer with this surprisingly simple recipe from Homestead Honey.

- If you find Stinging Nettle that’s past it’s prime for fresh eating, revisit the patch when it goes to seed. Gather Victoria has an excellent recipe for Nettle Seed and Dandelion Blossom Energy Bars.

- Looking for something savory? Try this Stinging Nettle Spanakopita, a type of Greek pastry, from Learning and Yearning.

- Nettle Cordial is another fun option, and you can use the leftovers to create tasty nettle fruit leathers. Check out these recipes from Craft Invaders.

- For easy-to-take medicinal support, create your own Simple Nettle Tincture with this recipe from Documenting Simple Living.

- If you’re like handcrafts, try making your nettle yarn with this article from Mother Earth News.

Edible Wild Weeds

Looking for other edible wild weeds?

- Foraging Chickweed

- Foraging Yarrow

- Foraging Wild Violets

- Foraging Pineapple weed

- Foraging Fireweed (Rosebay Willowherb)

- Foraging Japanese Knotweed

- How to Make Wild Foraged Clover Flower

- Using Red Clover for Food and Medicine

- Foraging Thistle

- Foraging Burdock for Food and Medicine

Can you use dwarf nettle in the same way? I would like to make a tincture but have only been able to locate dwarf nettle where I live. Thank you!

I’m not familiar with the term “dwarf nettle”. Different areas often have different common names for plants. Do you happen to know the scientific name? There are actually several varieties of nettles and they don’t all necessarily have the same properties.

It’s listed in this article under look-alikes, the scientific name is urtica urens! From what I can find it seems to be very similar in it’s properties. Thanks again.

Yes. Ok, so from what I can see it looks like urtica urens is often used primarily for skin issues. Is there a specific benefit that you’re looking to get from the nettle? It may have some similar properties but probably won’t have all of the exact same properties.

do you think it’s worth making tea of leaves in late summer? or at that point, is most of the plant’s goodness headed to the roots in preparation for winter? i am growing a plot of nettle (i live in a city, little access to wild areas), and by late august the leaves look tired.

If the leaves look tired I wouldn’t harvest them. I would just wait for spring to come back around and then you can harvest and preserve them then.

Perfect! Thank you. We have an area here with acres upon acres of stinging nettle. I’m looking forward to trying everything I can with them.