Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

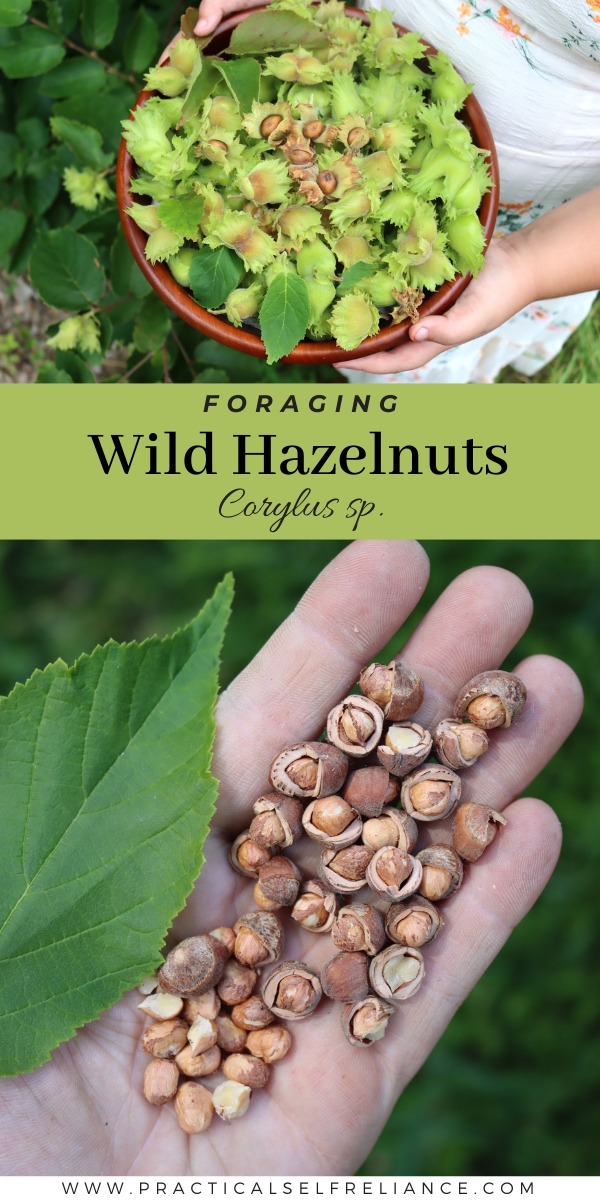

Wild Hazelnuts (Corylus sp.) can be incredibly prolific, providing a nutritious food source to humans and wildlife alike. The nuts are tasty, and store well in the shell, and believe it or not, the leaves and catkins are edible too!

Wild hazelnuts are one of the best wild sources of calories in late summer. They’re absolutely delicious, and while they’re a bit smaller than cultivated hazelnuts, they taste pretty much the same.

The main benefit, of course, is that they’re free, and they come with the satisfaction of having harvested your own meal from the wild. Few things get the little ones excited about the great outdoors more than the promise of harvesting the ingredients for homemade Nutella from the woods!

What are Hazel Trees?

Hazel are a species of small deciduous trees and large shrubs in the Corylus genus that produce Hazelnuts. Depending on where you live, you may also hear them called filberts or cobnuts.

They’re part of the Birch of Betulacaea family, though some authors separate them into their own family Corylacaea. Hazels are relatively long-lived, and it’s not uncommon for some species to reach 40 years or older.

Hazels are native to the temperate northern hemisphere. There are species of Hazel native to North America, Europe, Caucasus, and Asia, including China, Tibet, and Japan. You’ll most likely find the American Hazel (Corylus americana) and the Beaked Hazel (Corylus cornuta) growing wild in the United States.

You may also find Common Hazel (Cirylus avellana), which people commonly grow for hazelnuts or as hedges. There are many commercial cultivars of the Common Hazel available today.

Are Hazel Trees Edible?

All hazelnuts are edible, safe, and healthy, raw or cooked. Many foragers find their flavor to be milder and sweeter once roasted.

While not common today, you can also eat Hazel leaves. Folks of the past used them as sustenance, but many people collecting them today are herbalists who use them for medicinal purposes rather than nutrition and flavor. Herbalists may also use the catkins or the bark, which was once a common ingredient in external preparations.

If you have a nut allergy, avoid eating hazelnuts until you consult your physician.

Humans aren’t the only ones who can enjoy Hazels; they’re great for livestock, too. The foliage is an excellent forage for livestock, and hazelnuts are great for pigs and wildlife.

Hazel Medicinal Benefits

Hazelnuts are incredibly nutritious. They are high in antioxidants, fiber, and healthy fats like omega-6 and omega-9. They also have good folate, vitamin B6, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc levels.

Incorporating them into your diet may have heart health benefits. In 2012, researchers had participants consume a diet where 18 to 20% of their daily calorie intake came from hazelnuts. The participants saw reduced cholesterol, triglycerides, and bad LDL cholesterol levels.

Researchers also found that hazelnuts have particularly high levels of antioxidants called proanthocyanidins compared to other nuts like pecans and pistachios. These antioxidants are believed to protect against oxidative stress and may help prevent or treat cancer.

Today, we focus on the nuts, but through the ages, the leaves, bark, flowers, and catkins were all part of medicinal remedies. Herbalists have used the catkins, bark, and leaves to make teas, the catkin tea for colds and flu, the bark tea for fever, and the leaf tea for diarrhea. They also used the bark externally to treat cuts and boils.

In traditional Iranian medicine, hazel leaves have a long history of use. In the past, they commonly used an infusion of hazel leaves to treat liver issues, but it’s still in use today for treating edema, hemorrhoids, phlebitis, and varicose veins.

Modern research supports the use of hazel leaves in traditional medicine. Studies have found that hazel leaves contain high levels of phytochemicals, mainly phenolic compounds, and may have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities. Researchers in a 2023 study on the potential health benefits of hazel leaves predict that the leaves may have therapeutic effects for cancer, lipids, atherosclerosis, and diabetic complications.

Where to Find Hazel

Hazels have an extensive range and can be found throughout the northern hemisphere anywhere there is an appropriate temperate climate. Hazel species grow wild in North America, Europe, the Caucasus, and parts of Asia, including China, Tibet, and Japan.

Hazels will grow in woodlands, meadows, abandoned fields, forest edges, railways, stream valleys, fencerows, pine barrens, and gardens. Hazels will grow in full sun or partial shade. They’re often an understory species but are more common in open woodlands than those with dense canopies.

They’re hardy shrubs and will tolerate nearly any soil type, including acidic, neutral, and alkaline soil and sand, clay, loam, and silt. However, Hazels need areas that are adequately moist but well-draining. You won’t find Hazels growing in boggy or swampy areas.

It may seem counter-intuitive, but if you want to grow Hazel, it’s best not to go overboard enriching the soil. Hazel trees in very rich, productive soil tend to produce more foliage and fewer hazelnuts.

When to Find Hazel

Hazels are perennial deciduous trees and shrubs. You may see them year-round, but they’re much easier to identify in the summer when they have foliage.

Early on in the season, you can spot the developing nuts, and we see them in late May or early June here in Vermont.

Depending on where you live and what species grows in your area, you may be able to harvest hazelnuts from July through October. In southern areas like Georgia, they ripen as early as July. In northern areas, like Maine, they may ripen as late as October.

While many people wait until the husk turns brown to harvest, hazelnuts are ripe weeks before this. To beat the squirrels to the hazelnuts, gather them as soon as they’re ripe. Pry a few husks open in late summer, and if the top half of the shell is brown, they’re ready to harvest. When they’re underripe, the shell will be cream-colored rather than brown.

I’ve found that here in Vermont, the best time to harvest is late August, but you’ll have to adjust that based on your local conditions.

Identifying Hazel

Hazels are deciduous trees or shrubs that lose their leaves in the fall. The species you’ll find in North America typically reach heights of 8 to 26 feet tall. However, some species, like the Turkish Hazel (Corylus colurna) of southeastern Europe and southwest Asia, are larger, occasionally reaching 82 feet tall.

Hazels are often multi-stemmed and have wide-spreading or spherical shapes. You’ll often find them growing dense patches because they can spread by sending up suckers from underground rhizomes.

Hazel Leaves

Hazel leaves are rounded, simple, and alternate with pointed tips. Depending on the species, they may be 2 to 6 inches long. They may be elliptic, egg-shaped, oval, or obovate. They’re dark green above, paler below, and coarsely double-toothed on the margins.

Hazel leaves may also have a crinkled appearance and be soft to the touch. Most species have hairy or downy leaf undersides, but the extent varies with species. The upper sides of the leaves may also be sparsely hairy. Hazel leaves usually turn yellowish in autumn before dropping.

Hazel Stems

Hazels are usually multi-stemmed trees or shrubs. The stems tend to form clumped at the base and may appear crooked or leaning, often with zigzagging twigs. It’s common to find them with 6 to 40 stems per clump. They reproduce through suckers which grow from underground rhizomes.

Most species you’ll see in the United States and Canada, including the American Hazel, Beaked Hazel, and cultivated Common Hazel, will range in height from 8 to 26 feet. Some other species may get taller. Each stem is usually 0.75 to 2 inches in diameter.

Young Hazels typically have smooth gray or gray-brown bark. As it ages, it develops white lenticels (corky pores) that eventually develop into a netted or crisscross pattern. In some species, like the Common Hazel, the bark on older hazels may also start to peel.

New twigs of the American Hazel are typically reddish, brown, or grayish and densely covered with sticky, glandular hairs. Beaked Hazels’ new twigs are typically greenish, yellowish-tan, or light brown and maybe hairless or covered in minute hairs. Common Hazel’s young stems are generally brownish and hairy. Typically, the stems of all three species become smoother in the second year.

Hazel Flowers

Each Hazel tree has both male and female flowers, which are wind-pollinated. The male flowers form in catkins in summer or fall. They remain on the tree and open and release pollen in the winter or early spring when the female flowers open. American Hazel catkins typically hang, drooping from small stems. In contrast, the catkins of the Beaked Hazel are usually directly or almost directly attached to the twig and sometimes held horizontally or upright.

The catkins are usually greenish or yellowish-brown and 1.5 to 3 inches long. They form on 1-yeard old branches. The female flowers are tough to spot. They form during the winter or early spring on the same branches as the catkins. They are bud-like, and when they open, they spray red styles at the tip.

Hazel Fruit

After the wind pollinates them, the female flowers develop into oval fruits.

Beaked Hazelnuts typically form in groups of six, American Hazelnuts form in groups of five, and Common Hazelnuts form in groups of one to four.

With the husk intact, they’re usually ½ to 1 inch long, depending on the species.

Beaked Hazelnuts get their name from their stiff green husks, which have a distinctive long tubular beak at least twice as long as the nut, ruffled at the tip and covered in tiny spines.

Other Hazel species have a similar stiff green husk but lack a distinctive beak. The American Hazels’ husks also have ruffled tips and are usually covered in glandular white or red hairs.

These husks are up to twice as long as the fruit. However, as they dry to an orangy-brown, they split open to reveal the nut.

The Common Hazels’ husks are much shorter and only enclose about three-quarters of the nut. These also turn brown as they ripen and peel back to release the nut.

The nuts ripen to a smooth, light brown. The shell is hard. Beaked hazelnuts have rounded tops, while American hazelnuts tend to be flatter on top.

Hazel Look-Alikes

Hazels are sometimes mistaken for the similarly named Hazel Alder (Alnus serrulate). However, Hazel Alder differs in several noticeable ways:

- Hazel Alder usually grows in wet areas like streambanks and bogs.

- Hazel Alder produces cone-like fruit with winged nutlets (seed).

- The female flowers of Hazel Alder are bright red, upright cylinders about ¼ inch long clustered in groups of 2 to 5 at the twig tips.

Another look-alike with a similar name is Witch Hazel (Hamamelis spp.). However, it too differs in a few easy-to-spot ways:

- Witch Hazel has light brown bark, which may be smooth or scaly with reddish-purple inner bark.

- Witch Hazel leaves have large, wavy teeth along the margins.

- Witch Hazel flowers have distinctive yellow (occasionally orange or reddish) flowers with four ribbon-shaped petals and four stamens that grow in clusters.

- Witch Hazel fruits are hard woody capsules, each containing two black seeds and split explosively at maturity.

Lastly, Hazel can be confused with Winter Hazel (Corylopsis spp.). Winter Hazel can be distinguished in the following ways:

- Winter Hazel is small and usually only reaches 4 to 6 feet tall.

- Winter Hazel branches have a zigzag form and light brown bark.

- Winter Hazel has yellow funnel or bell-shaped, fragrant flowers that form in long arching, pendulous racemes.

- Winter Hazel fruits are dry brown capsules that each contain two black seeds.

Ways to Use Hazel

Hazelnuts are healthy, delicious, and easy to use. You want to begin checking the bushes for hazelnuts in late summer and early fall. You can harvest the nuts when the husks are still green or starting to get reddish or brown patches. Usually, if you wait until the husk is entirely brown and dry, the squirrels will have eaten them all!

You don’t need to peel hazelnut husks off in the field. Grab entire clusters of nuts and twist them as you pull them off the bush. The hairy husks of Beaked Hazel can be irritating, so you may want to wear gloves to harvest.

You can use a float test on fresh hazelnuts, which expert forager Sam Thayer recommends. Place fresh hazelnuts in a bucket of water and give them a stir. Any hazelnuts that float are usually bad or infested with worms. This test won’t work with dry hazelnuts.

If you want, you can husk and use your hazelnuts right away. Both can be peeled by hand, shelled, and eaten right on the spot. However, Sam has also devised clever ways of processing larger amounts of hazelnuts rather than hand-peeling them.

American hazelnut husks are much easier to remove when they’re dry. Find a spot you can lay them out where the squirrels won’t get to them for a couple of weeks until the husks turn brown. At this point, they are much easier to hand process, or you can use Sam’s bulk technique, dumping a few gallons into a wooden barrel and stepping on them until the husks are separated from the shells. Then, pick out the nuts.

The tricky husks of baked hazelnuts can be harder to process. Sam recommends burying them in wet sand or mud for about one month rather than drying them. After this point, he places them in a sack and steps on them to loosen the now rotting hulls. Then, you can pick out the separated nuts.

After you remove the husks, you can store your hazelnuts. They keep well in the shell. When you’re ready to use your hazelnuts, you’ll need to shell them. You don’t need fancy tools; you can crack the shells with a hammer or large, sturdy mortar and pestle. However, there are some nutcrackers available that are designed for hazelnuts, which may make the process easier.

Once they’re out of the shell, hazelnuts are easy to use. Historically, they have been an important food source for humans and animals wherever they grow. Native Americans used them as an essential source of winter calories, mashing them into cakes and boiling them into soup. In northern Europe, archeologists have found evidence that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers used hazelnuts, too!

Hazelnuts are a great snack that’s high in protein and healthy fats. They are also excellent additions to baked goods, granola, and trail mix. You can also use them to make hazelnut milk or use them in savory recipes like soups, pesto, or crusty toppings for meat and fish.

Don’t forget that you can eat the hazel leaves too! Hazel leaves are best harvested in the spring or summer before they dry out and change color in the fall. The hairs on the leaves aren’t a problem after cooking, and they have a mild flavor. Use them as you would other greens, in soups, stir-fries, or sautéed by themselves.

You can also use Hazel medicinally. Historically, herbalists used the catkins, leaves, and bark in teas and other remedies for treating various conditions. Though further research is still needed, modern science has found that hazel leaves have many health benefits. Use your best judgment and experiment with hazel-leaf tea or tincture.

Hazel Recipes

- If you enjoy cocktails, check out this delicious Hazelnut Liqueur recipe from The Forage Field.

- Satisfy your sweet tooth with this Wild-Bleuberry Hazelnut Cake with Meadowsweet Cream recipe from the Forager Chef.

- Use your hazelnut harvest immediately with this Green Hazelnut Chocolate Brownie recipe from The Hedgecombers.

- Whip up something a bit more savory with this Hazelnut and Oregano Pasta Recipe from BBC Good Food.

- Check out this delicious, foraged Wild Ramps and Hazelnut Pesto from Beyond Sweet and Savory.

- Make good use of the leaves with this fun recipe for Hazel Leaf Crumble Parcels from Nature Nuture Sussex.

Wild Nut Foraging Guides

Looking for more edible wild nuts to forage this year?

- Foraging Black Walnuts

- Foraging Butternuts (White Walnuts)

- Foraging Beechnuts

- Foraging Shagbark Hickory