Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Honey mushrooms are not for beginning foragers, but learning to identify honey mushrooms is well worth the effort!

This article was written by Timo Mendez, a freelance writer and amateur mycologist who has foraged wild mushrooms all over the world.

Honey Mushrooms are a cult classic amongst veteran mushroom hunters. They’re not as popular as other edible mushrooms, but amongst their fans, they’re adored and every bit worthy of pursuit. Not to mention, they have a fascinating parasitic ecology worthy of a David Attenborough documentary.

Honey Mushrooms are not often sought out by those just starting to navigate the wild world of mushrooms. They are less known and a bit trickier to identify, requiring proper cooking techniques to ensure a delightful experience. I generally consider this mushroom for more seasoned foragers looking to amplify their existing culinary repertoire, but newcomers don’t be dissuaded! With proper care, knowledge, and the help of this guide, they can be easily identified and cooked up into delicious meals.

That’s not all though!

Honey Mushrooms have a unique relationship with an even more cherished and strange mushroom known as “Shrimp Of The Woods.” This rare delicacy is prized for its shrimp-like texture and delicate but delicious flavor. Interestingly, Shrimp Of The Woods is a remarkable phenomenon that occurs when another mushroom parasitizes the honey mushroom! This results in a one-of-a-kind delicacy highly coveted by mushroom enthusiasts.

Ecology Of Honey Mushrooms

Ecologically speaking, Honey Mushrooms are a unique marvel unlike anything else known in nature. This is easily portrayed by the fact that one population of Honey Mushrooms actually forms part of the largest organism on the planet!

We’re not talking about the caps or stems, but rather the massive network of fungal mycelium they grow from. The largest known network is made up of a single genetic individual found in Oregon, stretching over thousands of acres and several kilometers across (Ferguson, 2003).

Estimates suggest this fungus could be around 2,500 years old! Impressive right?

Honey Mushrooms are exceptional not only for the massive size of their networks but also for the unique ecology that enables this growth. They are, in fact, brutal pathogens that display seemingly aggressive behaviors.

Honey Mushrooms not only consume dead plant materials (as a saprophyte) like many other fungi, but they have parasitic behaviors that delve them into the realm of predators. They infect trees, kill them, and then consume their remains long after their demise. Sounds a bit scary, huh? This is quite the opposite of the mycorrhizal fungi we mushroom hunters often go after, these form important beneficial relationships with these very same trees!

Honey Mushrooms employ a unique fungal structure called a “rhizomorph” to aid in their hunt for prey. These are root-like growths of mycelium that are thick, dense, black, and about the width of a shoestring. It is why Honey Mushrooms have another common name, “The Shoe String Fungus.” Honey Mushroom rhizomorphs are readily visible to the naked eye and can often be found on the forest floor or the woody material of their targets. These structures grow rapidly, enabling the fungus to locate new hosts and better connect with their vast network, much like the “Fiber Optic” of the mushroom kingdom.

While Honey Mushrooms are often considered a pest species, it is important to note that their role as a pathogen also plays an important part in ecosystems. They attack unhealthy trees and make openings in the forest which can promote biodiversity. They are often called “Meadow Makers” because of their ability to make vast clearings. This being said, their prominence has also been exacerbated by land use practices, human-aided dispersal, and climate change. In this sense, their pathogenic characteristics are cause for concern in many forest ecosystems.

Taxonomy and Identification Features Of Honey Mushrooms

There are many different species of Honey Mushrooms, all of which belong to the genus Armillaria. The most well-known is Armillaria mellea and it is what you often find described in old guidebooks. This being said, what was historically classified as Armillaria mellea has now been broken up into various species.

Most of these have unique features or geographic distributions that make their identification simple, but others are more cryptic and require DNA analysis for proper identification. There are about 10-12 species recognized in North America and over 25 across the world.

While all Armillaria species are generally considered edible, I will mention that a small percentage of individuals have allergic reactions to these mushrooms. While this is usually caused by improper cooking (I’ll talk about that later), it is common enough that some mycological associations don’t serve these mushrooms for large banquets or events.

Some individuals believe certain species may pose higher risks to allergic reactions than others, while others say those found on softwoods are riskier. Neither of these has been confirmed, but it is something to consider. I’ll talk more about the toxicity and how to safely consume it later in the cooking section.

Common North American Honey Mushrooms

These are some of the most common species of honey mushrooms in the United States:

Honey Mushroom (Armillaria mellea)

This is the classic Honey Mushroom, most easily distinguished from the others by its yellow-golden cap. It occurs in Eastern North America, Europe, and Asia.

Bulbous Honey Mushroom (Armillaria gallica)

This Honey Mushroom has a darker cap color and a bulbous stem when young. They often grow less clustered than the classic honey mushroom.

It occurs in eastern North America and is identical to Armillaria calvescens in morphology.

Western Honey Mushroom (Armillaria ostoyae)

This is the Western version of the classic Honey Mushroom. It can be differentiated by its darker cap color, dark scales, and dark annulus.

Ringless Honey Mushroom (Desarmillaria tabescens)

This is the ringless Honey Mushroom which is identified by its lack of annulus. It occurs in Eastern North America, Europe, and likely Asia.

The species Desarmillaria ceaspitosa is the variant found in Western North America.

Armillaria sinapina

This species is found across North America and is identified by its brown color, red tinges, and golden-yellow universal veil that covers the young mushrooms.

Where to Find Honey Mushrooms

Honey Mushrooms are incredibly opportunistic and will grow in a diverse range of different habitats. They predominantly occur in temperate forests dominated by Oak or Beech. Their preferences include hardwood tree species such as Oak, Beech, Chestnut, Maple, Sycamore, Cottonwoods, Birch, and many different types of fruit trees. It is not uncommon to also see them planted with ornamental tree species in urban environments.

This being said, they can commonly occur in association with different conifers, such as Douglas Fir and Ponderosa Pine. The latter is particularly true in the Pacific Northwest and other parts of Western North America. There is no need to go into great detail about the specific habitats for Honey Mushrooms since they are so widespread. Simply check your local woods at the right time and keep your eyes peeled!

Identifying Honey Mushrooms

Once you familiarize yourself with Honey Mushrooms there is little likelihood of mistaking them for other mushrooms. This being said, for amateur mushroom hunters identification can be tricky and should always be done with caution. When picking a mushroom for the first time, I always recommend to have them properly identified by a professional.

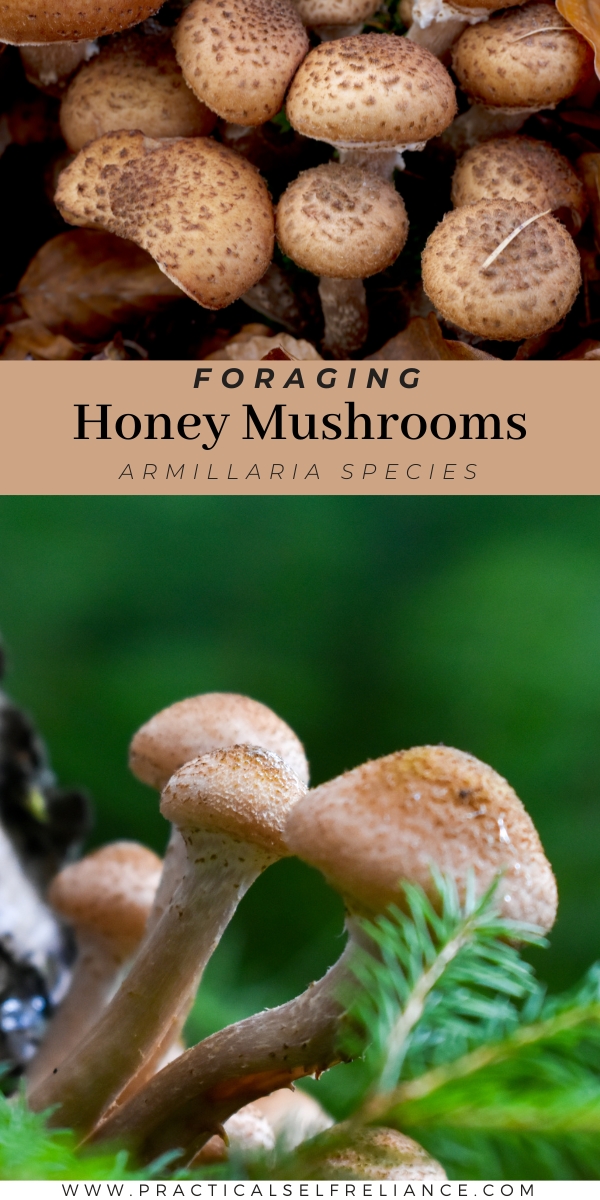

Honey Mushrooms often grow in dense clusters, sometimes with over a dozen mushrooms emerging from a single bouquet. The mushrooms range from just a couple inches in size when young and easily grow up to 10 inches once mature. Mushrooms often occur on the trunks, bases, and fallen limbs of trees. Certain species have less clustered habits and often emerge directly from the ground.

Honey Mushrooms have golden-yellow caps that are covered with fine fibrous scales. Caps are just about an inch wide when young and expand to over 5 inches once mature. Young specimens have closed caps and are covered by a cotton-like tissue known as the universal veil. Some species have darker-colored caps as discussed in the above section.

Most Honey Mushrooms also have a cottony ring that occurs on the stem below the cap. The margin of this ring often has a yellowish color. On young mushrooms, the ring attaches to the cap, completely covering the gills of the mushroom. As the name suggests, Ringless Honey Mushrooms do not have this distinctive ring. The stem of Honey Mushrooms is tough, fibrous, white in color, and usually tapers towards the base.

One of the other distinctive features of Honey Mushrooms is their white spore print. Making a spore print at home is usually not necessary as mature mushrooms generously deposit spores directly onto neighboring mushrooms and vegetation, coating them with a white powdery print.

Identification Features Of Honey Mushrooms

- Growing in dense clusters, sometimes with over a dozen mushrooms.

- Golden-yellow caps covered with fine fibrous radially arranged scales.

- Cottony ring on the stem below the cap, which often has a yellowish color.

- Stem is tough, fibrous, white in color, and usually tapers towards the base.

- White spore print which is generously deposited in the surroundings.

- White to slightly pinkish flesh.

As always, proceed with great caution if you are unfamiliar with Honey Mushrooms. If you have any doubts, throw them out! Even better, don’t pick them to begin with if you are not 100% sure!

Honey Mushroom Lookalikes

There are a few Honey Mushroom lookalikes, and one of them can be deadly! Make sure to familiarize yourself with these species before picking honeys.

Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata)

This species contains the same deadly toxins found in the deadly Amanitas. Take great care not to mistake Honey Mushrooms for this species. They both grow on decaying wood, have rings, and can grow in clusters.

- Galerina marginata has a smaller stature, usually 5-10 cm in size, with a thin dark stem, while Honey Mushrooms can grow up to 20 cm in size and have a tough, fibrous, white stem.

- Galerina marginata has a rusty-brown cap, while Honey Mushrooms have a golden-yellow cap (can be darker in some species) covered with fine fibrous radially arranged scales.

- Galerina marginata has brown gills and spores, while Honey Mushrooms have white gills and spores.

- Galerinas are also much more fragile and easily break, as opposed to the more sturdy Honey Mushrooms.

Shaggy Scaley Cap (Pholiota squarrosa)

- These mushrooms have much larger and more developed scales on their caps.

- They have a brown spore print, as opposed to the white one seen in Honey Mushrooms.

- The stems have well-developed scales and brown color.

- Shaggy Scaley Caps mushrooms are not considered deadly, but they are toxic.

Velvet Shank (Flammulina velutipes)

- Velvet Shanks (also known as Wild Enoki) have brown velvety stems and smooth often viscous brown caps

- They have no ring and are generally much smaller than Honey Mushrooms

- These are also edible and occur during colder times of the year

Jack O’ Lantern (Omphalotus olearius)

- Mistaking these for Honey Mushrooms would be difficult, but their clustered growth habit on dead wood could confuse novice foragers.

- They are generally orange in color and have smooth caps and stems.

- The gills are decurrent, meaning they run down the stem of the mushroom.

- Orange-colored flesh and white-yellow spore print

When To Forage Honey Mushrooms

Generally speaking, Honey Mushrooms are most plentiful during the peak of mushroom season. You can find Chanterelles, Black Trumpets, Boletes, and many other species during this time of the year depending on where you are located. Most mushroom hunters I know, myself included, rarely go out searching specifically for Honey Mushrooms. Instead, we harvest them as a bonus, especially if we got skunked (mushroom hunting term used for not finding mushrooms) with the other species.

Eastern North America

In the Northeast, Honey Mushrooms typically occur from August to November. They will usually start with the end of the summer rains and fruit until temperatures get too cold.

Pacific Northwest

In the Pacific Northwest, Honey Mushrooms are fall mushrooms occurring from September to November. Along the coast where the climate is milder, they can occur much earlier or later in the season.

California

In California, you can find Honey Mushrooms from September to February, although peak season is usually around October. In the mountainous regions and areas with colder climates, they are limited to the fall, but near the coast, you can find them into February!

Colorado and Southwestern Sky Islands

Here you find Honey Mushrooms during the summer monsoons. This usually occurs during July and August, but they could appear whenever the temperatures are favorable and the rain is present!

Harvesting Honey Mushrooms

When harvesting any wild food, make sure to take great care and respect for the forest you are in. Do not leave trash, cause erosion, or damage the environment in any way.

Like most wild mushrooms, but especially in this case, Honey Mushrooms are best picked when they are young. The best specimens are those that have their caps completely closed and still have the veil covering their gills. Many foragers only pick them when they are in this stage because they are truly not as tasty once they are more mature, and there is a higher risk of intoxication.

While I usually suggest leaving small mushrooms behind to promote the reproduction of the mushroom, you can make an exception for Honey Mushrooms. Their pathogenic nature and the fact their presence has been exacerbated by human activity makes it a-okay to pick all the young specimens you want.

For harvesting, I usually recommend going from below and harvesting entire clusters together. Remove any excess dirt and debris before putting them in your bag/basket. Alternatively, you could cut each mushroom with your knife, if that’s what you prefer.

Again, I generally advise people to transport mushrooms in baskets to promote spore dispersal, but we can make another exception in this case. It is best if you take great caution to avoid dispersing the spores to not introduce them into new habitats where they could cause negative impacts. The best way to do this is by simply putting them in a bag and leaving them there until you arrive home.

A Parasites Parasite: Shrimp Of The Woods

As mentioned in the intro, Honey Mushrooms can become parasitized by another mushroom known as Shrimp Of The Woods. These are also called “Aborted Entolomas” which also happens to be the meaning of their scientific name, Entoloma abortivum. The exact science of this is complex and you can read more about it here on the page of the late mycologist Tom Volk. If you’re really geeky, you can read one of the latest studies on the subject here.

Anyhow, Shrimp Of The Woods has an unusual growth form. They are small, white, wrinkly, and clustered blobs with a rubbery texture and are almost always found growing near Honey Mushrooms which they parasitize. They are often also described as “brain-like” and can display a slight pinkish hue. Their distinct form makes them easy to identify, even for amateurs. There is also an unaborted form that looks like a regular step-cap mushroom but these are more difficult to identify and have some toxic lookalikes.

The Shrimp reference is not so much because of its taste, but more because of its bouncy and shrimp-like texture. The taste is pretty neutral but has a pleasant mushroom flavor. To cook these it is recommended to sear them well with butter or oil and get them a bit brown. Add onion, garlic, lemon, or whatever you’d like to go along with them!

Cooking Honey Mushrooms (Safely!)

Honey Mushrooms can be delicious additions to many meals. That’s why we harvest them right? Yet, Honey Mushrooms are pretty particular and require proper preparation to be good for the table.

Note On The Safety Of Honey Mushrooms

It is important to mention Honey Mushrooms are TOXIC when raw or improperly cooked! They’re not deadly, but they could cause some severe sickness and be potentially hazardous to individuals with sensitivities or other illnesses. Also, while it only affects a small percentage of people, some folks do have adverse reactions to eating this mushroom in general. These can range from gastrointestinal discomfort to flu-like symptoms

This may also be linked to improper cooking, overconsumption, or consumption of mature specimens, but there hasn’t been much research conducted on this subject. Some sources suggest toxicity may also go up if harvested after a frost.

Note that Honey Mushrooms are consumed traditionally in many different cuisines without issue. In Europe, I’ve seen them sold jarred countless times at large chain grocery stores. In Poland, I met numerous people who preserved them at home like this as well. I personally haven’t ever had issues consuming them. Not to mention, digestive problems like this aren’t something unique to Honey Mushrooms.

For example, the highly cherished Morel Mushrooms are also toxic when consumed raw or undercooked and a handful of people also experience negative side effects when consuming perfectly cooked Morels. Personally, I can attest that Chicken of The Woods is a mushroom I can’t digest. Even parboiled and perfectly cooked, I still suffer mild digestive issues after consuming them.

Even still, it is best to take precautions when trying this mushroom. My recommendation is that if this is your first time consuming Honey Mushrooms do so in moderation. If you are cooking for a fair number of people, it is wise to cook them separately to not taint a whole dish. This way, people can try them out in moderation if they’ve never consumed them before.

Lastly, it is best to undergo the following practices to reduce the risk of digestive issues:

- Consume only the caps of young healthy mushrooms, ideally before they have opened up. The stems are pretty tough and fibrous, so I could understand how some folks don’t digest them well.

- Parboil the mushrooms in water for 15 minutes and discard the water. This not only ensures they are properly cooked, but it also reduces some of the slimy texture that many folks don’t enjoy about mushrooms.

- After parboiling them, add them to your dish and continue cooking them along with the other ingredients to ensure they are well-cooked.

Honey Mushroom Recipes

Now, when it comes to actually incorporating Honey Mushrooms into recipes there are endless possibilities. The flavor is pretty mild and a bit nutty, but the texture is nice and bouncy. They are naturally a bit slimy, but this can make a great thickener for soups or sauces. Imagine the same texture you get from okra or prickly pear leaves. They also go great with scrambled eggs or mixed into saucy stir-fries.

Preserving Honey Mushrooms

For preserving Honey Mushrooms, I recommend either freezing them after cooking or pickling them. Personally, I’m not a huge fan of the pickles, but they are common in Eastern Europe so I figured I’d mention it here.

For freezing, simply par-boil them for 10-15 minutes in water and then discard the water. Throw them into a hot pan with some oil and then fry them for another 5-10 minutes. Feel free to add garlic, onion, and other seasonings. I like to add a bit of parsley at the end of cooking. Once done, let them cool down and freeze them. Like this, you can heat them for eating or easily incorporate them into other meals.

I personally have never made the pickles, but like I said they are very common in Eastern Europe. To make the pickles, simply boil them for about 20 minutes and discard the water. Then add them to your favorite pickling vinegar brine. Pressure can them if you want to store them for longer than 2-4 weeks. People commonly add garlic, onion, black pepper, mustard seed, allspice, bay leaf, and other aromatics. The brine and the mushrooms come out a little bit slimy which is not something many people like, but hey if you are adventurous, give it a try!

Mushroom Foraging Guides

Fill your basket with these mushroom foraging guides!

- Morel Mushrooms

- Chaga Mushrooms

- Birch Polypore

- Tinder Polypore

- Witches Butter Mushrooms

- Puffball Mushrooms

- Shaggy Mane Mushrooms

- Reishi Mushrooms

- Turkey Tail Mushrooms

- Dryad’s Saddle