Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

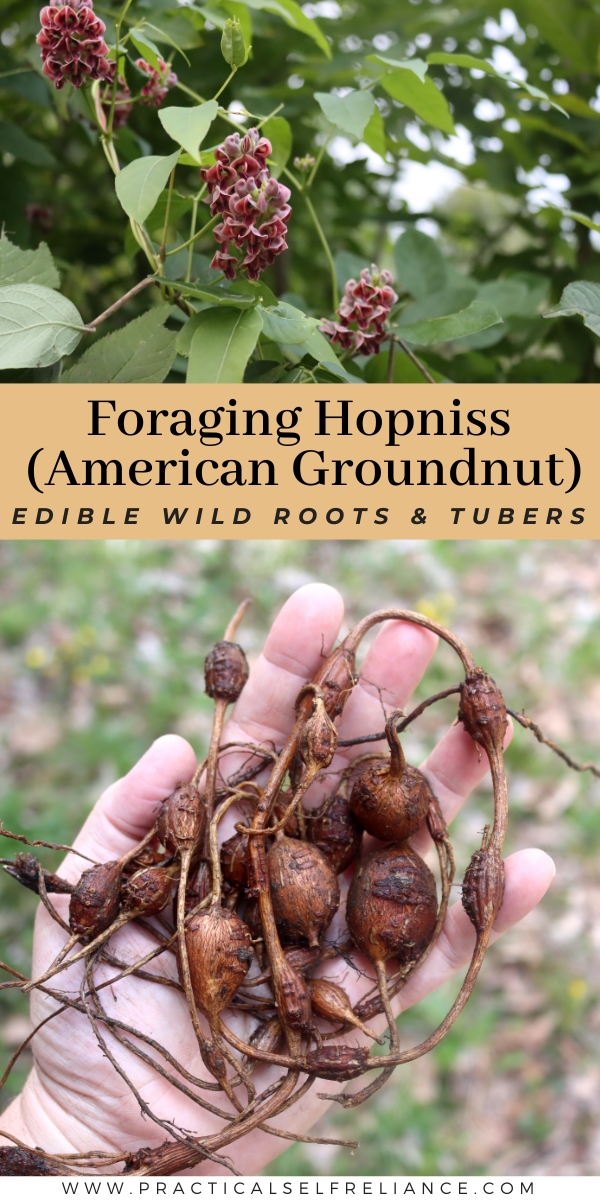

Hopniss (Apios americana) is a traditional wild food source, producing both edible tubers and seeds. Sometimes called “Indian Potato” or “American Groundnut,” the chains of starchy tubers can be peeled and boiled for a calorie-rich meal.

Hopniss is a wild edible tuber that’s a bit like a perennial vining potato. The plants thrive in wet locations near ponds or ditches, provided they have somewhere to climb. Underground, the tubers form chains of pearls that are easy to identify (even when the plant is dormant).

The tubers are peeled and cooked like potatoes, and to me, they taste an aweful lot like parsnips. Starchy, and a bit sweet with an earthy finish.

You can find them growing wild all over the US, and they’re even starting to be cultivated by adverturous permaculture gardeners.

Above ground, the easiest way to spot them is mid-summer, when they produce beautiful and distinctive flower clusters on their vines.

What is Hopniss?

Hopniss is sometimes called the American groundnut, American hopniss, potato bean, potato pea, ground potato, wild bean, wild sweet potato, bog potato, cinnamon vine, Indian potato, hodoimo, or America-hodoimo. It’s an herbaceous, perennial vine in the Fabaceae or Pea family.

Hopniss is native to North America. Its natural range extends from Canada south into Florida and west as far as Colorado.

Is Hopniss Edible?

Hopniss produces two edible products: underground tubers and bean-like pods. Historically, Native Americans also used the tubers medicinally for treating certain skin conditions.

Hopniss should not be eaten raw. They contain harmful compounds called protease inhibitors that interfere with protein metabolism. Thankfully, these compounds are destroyed when you cook hopniss, making it safe to eat.

Expert forager Sam Thayer also reports that about 5% of the people he has seen eat hopniss developed an allergy to it after eating it a few times. He notes that people would become ill with vomiting and diarrhea even though they previously did not react to the plant. Sam notes that it may be environmental conditions, the tubers’ age, or other causes. Use caution the first few times you try hopniss.

Some permaculturalists note that hopniss vines make excellent forage for livestock like goats. These plants are handy to have around because they’re high in protein and fix nitrogen.

Hopniss Medicinal Benefits

Unfortunately, we have little information about Hopniss’s historical medicinal usage. Colonists in what’s now New England reported that Native Americans boiled the hopniss tubers to make a plaster to treat skin conditions like proud flesh, a type of persistent granulation tissue that occurs on an improperly healed wound.

Thankfully, modern research has rediscovered many of the benefits of hopniss. Hopniss tubers have some remarkable characteristics. Studies have found that they have abundant bioactive chemicals that demonstrate “bioactivities in antioxidant, anti-inflammation, anti-diabetes, anti-atherosclerosis, anti-hypertension, immunoregulation, anti-tumor and improvement in post-partum uterine involution.”

The tubers are protein-rich and may also help with blood pressure and cholesterol levels. One study in hypertensive rats found that when 5% of their diet was the hopniss tubers, they had a 10% reduction in blood pressure and decreased cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

A study on mice found that the plant may have lung benefits, too. The study found that mice who were given hopniss extract eight weeks before an acute lung injury or an influenza A infection had lower levels of lung inflammation.

A look into their specific makeup has also found that they contain important compounds like the isoflavone genistein, which protect against several forms of cancer.

While hopniss is overlooked by many Americans, here in its native range, in Japan and South Korea, hopniss has become an important food. Japanese researchers and websites have emphasized the benefits of consuming hopniss, and modern research concludes that hopniss can be an incredibly healthy part of your diet.

Where to Find Hopniss

Hopniss predominantly grows in eastern North America, from Ontario south to Florida and in some places as far west as the edge of Colorado. You may also spot it growing in places like Japan, South Korea, or England, where it has been introduced as a food crop or flower.

Hopniss thrives in full to partial sun and can live in dry or waterlogged soils. It usually grows along the sandy edges of rivers, lakes, and streams and in brushy wet areas. While it may tolerate other soils, plants growing in areas with rich, loose soil usually produce the most tubers.

Occasionally, you may actually find hopniss tubers sticking out of streambanks after high spring waters or flooding events. Hopniss tubers also often grow under other shrubs and dead stumps and logs.

I’ve found it in unlikely places, like growing along fences near riverbanks in urban areas. It just needs consistently moist soil and a place to climb, and fences near rivers or streams, even in densely populated areas, make the perfect habitat.

When to Find Hopniss

Hopniss is a perennial, but the above-ground vine is frost-sensitive and dies back completely in winter after a frost. In northern areas, hopniss vines come up around June and flower at the end of summer, usually in August or September. In warmer southern climates, you may spot Hopniss vines much earlier, and the plant may bloom in July.

The hopniss flowers give way to its bean-like seed pods in late summer or autumn. However, in the northern part of its range, hopniss may not produce seed pods at all. Instead, it spreads underground.

One of the most extraordinary things about hopniss is that you can harvest the tubers year-round except when the ground is frozen in northern areas. Some foragers find that young tubers less than one year old have the best flavor. These will be the small to medium-sized, smooth, regularly shaped, thin-skinned, yellow or reddish-brown tubers you find.

Identifying Hopniss

Hopniss has the classic legume characteristics that make it look like a large pole bean vine. Hopniss will grow up other plants or over open ground, sometimes forming large areas of dense tangles of vines. The plants sprawl over their supports but lack tendrils to grip and climb supports.

Its somewhat showy, fragrant, dense clusters of purplish flowers and bean-like pods can help identify this plant when they’re present. Digging a few tubers is a sure way to identify hopniss, though, as its tubers are distinct from other vining look-alikes.

Hopniss Leaves

Hopniss has pinnately compound, green leaves that are often partly folded along the midrib. Each leaf comprises 5 to 9 toothless ovate to lanceolate leaflets. Each leaflet is usually about 1 to 2.5 inches long.

Hopniss Stems

Hopniss has 3 to 20-foot-long stems that drape over other plants or open ground. The stems are usually green and covered in tiny hairs. They die and turn brown after frost.

Hopniss Flowers

Hopniss usually flowers between July and September. The pink, purple, or reddish-brown, fragrant flowers form in dense racemes, usually 3 to 5 inches long.

Hopniss Seed Pods

After flowering, plants in southern areas regularly produce clusters of green bean-like pods that grow 2 to 5 inches long. Plants in northern regions may have pods or may never produce seed.

Hopniss Tubers

Hopniss forms chains of 2 to 20 underground tubers connected to a central, tough rhizome. Most hopniss tubers are about 1 inch wide, 1.5 inches long, and egg-shaped. However, their size and shape are highly variable. They may be even smaller or as large as a grapefruit.

Young hopniss tubers less than one-year-old are usually reddish-brown or yellow with thin, smooth skin. These typically have noticeable, whiteish lenticels or raised pores. Older, larger tubers may be irregularly shaped and knobbly.

Hopniss Look-Alikes

Hopniss vines may be confused with Wild Yam (Dioscorea villosa). However, Wild Yam differs in several noticeable ways:

- Wild yam has simple, heart-shaped leaves with highly prominent veins.

- Wild Yam leaves are primarily alternate, though they are occasionally whorled near the base.

- Wild yam has clusters of small, inconspicuous flowers, usually green to brown or white.

- Wild yam rhizomes are long, dry, cylindrical, and run horizontally, bearing branches of creeping runners.

Hopniss can also be confused with bindweed species (Convolvulus), though they, too, differ in some easy-to-spot ways.

- Bindweed has simple, alternate, triangular, arrow, or almost heart-shaped leaves.

- Bindweed flowers are trumpet-shaped and usually white to pink but are occasionally blue, purple, or yellow.

- Bindweed has extensive root systems but no tubers.

Lastly, hopniss can be confused with another North American legume, the hog peanut or ground bean (Amphicarpaea bracteata). However, you can differentiate it in the following ways:

- Ground bean’s compound leaves have three leaflets.

- Ground bean produces white to pinkish or purplish flowers in loose clusters.

- Ground bean produces flat, oblong pea-like pods.

- Ground bean stolons touching the ground produce underground fleshy pods with inner nuts, similar to peanuts.

Ways to Use Hopniss

Hopniss is one of the wild plants that make an excellent staple crop. The tubers are nutritious, filling, and high in protein, vitamins, and iron. To prepare your hopniss tubers, you should begin by washing them well. You may also want to peel older tubers as they tend to have thicker, tougher skin than young ones, though the peels are edible if you’d like to leave them on the tubers.

As many of their common names suggest, they have much of the potato’s versatility. Hopniss tubers are excellent fried, mashed, or baked. You can boil or bake the tubers whole or chopped and add them to casseroles, stews, soups, and stir-fries.

However, their flavor does differ a bit from potatoes. Some foragers find it’s more like other root vegetables like the turnip. Expert forager Sam Thayer has spent a lot of time with hopniss and says he thinks they taste a bit like a cross between peanuts and potatoes.

You can also use your hopniss tubers to make flour. Cut your hopniss tubers into small cubes and slowly roast them until completely dry or dehydrate mashed hopniss. Grind these up to create flour that’s excellent in all kinds of baked goods like muffins, pancakes, and breads. Sam Thayer also reports that this flour makes a delicious hot cereal with a bit of butter and brown sugar.

Thayer also recommends utilizing the protein-rich tubers like refried beans. He runs boiled, peeled hopniss tubers through a meat grinder and adds a taco seasoning mix to make a tasty filling for burritos and tacos. He notes that this bean replacement pairs exceptionally well with venison.

You can also store hopniss tubers for later use. They keep well in a root-cellar type setting similar to true potatoes and other root vegetables. You can also pressure can or dry the cooked tubers for long-term storage.

If you live in the southern part of the hopniss range, you can also harvest the seed pods. These green bean-like pods can be boiled, sauteed, or steamed.

While hopniss may have seen more specific medicinal use in times past, our current knowledge of hopniss suggests that one of the best ways to use hopniss is just to eat it! Hopniss contains many helpful compounds that can help reduce blood pressure and cholesterol, reduce inflammation, and protect against cancer.

Hopniss Recipes

- One of the simplest, tasty ways to enjoy hopniss tubers is fried. Check out The Forager Chef’s easy recipe for fried hopniss.

- If mashed is more your style, check out this Tyrant Farms recipe for Hopniss Mash with Rosemary Brown Butter.

- These versatile root vegetables are excellent roasted, too. Try Hunt Gather Cook’s recipe for Root Vegetable Ragu with Polenta.

- Make this American Groundnut and Maitake Mushroom Chowder from Tyrant Farms for a warm, comforting, filling option.

In Abenaki, this is called apen, pl. apenak, from “pen” = downward (Sokoki Sojourn). Not related to the word “Abenaki” despite the similarity. According to Ethno-Botany of the Abenaki and other Northeast Tribes, “The tuber can be eaten raw or cooked. The nuts are boiled and used as a plaster on the flesh around healing wounds.” Just as you said! I’d be interested to learn what other sources you used.

Also, a great source on building a trellis to grow groundnut: https://www.ourtinyhomestead.com/groundnuts.html

Great post!