Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Indigo Milk Caps (Lactarius indigo) are a fun summer mushroom to identify in the woods, and they’re a choice edible species as well.

This article was written by Timo Mendez, a freelance writer and amateur mycologist who has foraged wild mushrooms all over the world.

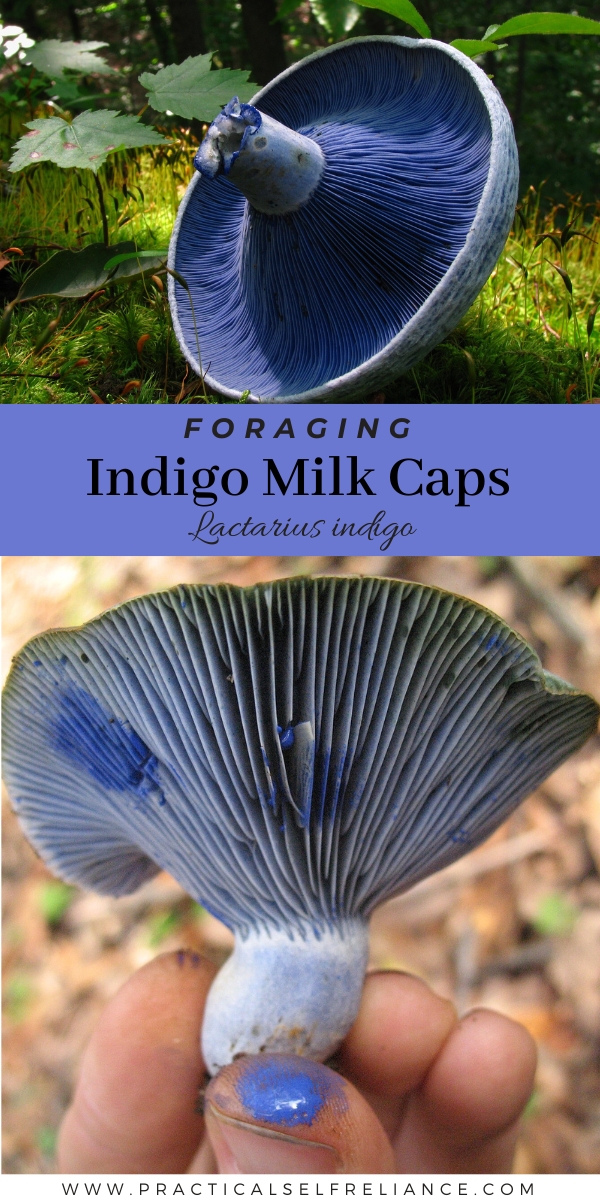

Indigo Milk Caps (Lactarius indigo) are some of the most iconic edible mushrooms in the entire fungal kingdom. Their blue color astounds those who have never seen them; with a vibrant indigo that seems more suitable for the delicate wings of butterflies or the plumage of a tropical bird.

The color is so blue and so unusual that some foragers refuse to eat it, despite it being a well-known and easy-to-identify culinary delicacy.

Not only this, they’re pretty darn easy to find. With their distinct blue tones, even a half-blind forager could spot them amongst the earthy tones of the forest.

Believe me, I’m not the best at spotting black trumpets or morels (I do know where the spots are though!) but Indigo Milk Caps can’t get away from me.

Plus, they’re about as close as you’ll get to seeing a Smurf in real life, so that’s pretty cool.

Natural History Of Indigo Milk Caps

Indigo Milk Caps are forest-dwelling mushrooms that live in a symbiotic association with pine and oak. They form what is known as “mycorrhizal relationships”, where the fungus exchanges nutrients obtained from the soil for carbon-rich sugars produced by the trees through photosynthesis. Because of this lifestyle, they cannot be tamed under conventional cultivation and only occur in the wild. While it has a pretty wide distribution in Mexico, Asia, and the eastern United States, it is completely absent from Europe, the western United States, and western Canada. One exception is that they can be found in the southwestern Sky Islands of the United States (New Mexico, Arizona, etc.).

The Indigo Milk Caps belong to the genus Lactarius, which is sometimes simply known as the Milk Caps. This genus includes the “Saffron Milk Caps” which are highly valued and sought after in several European countries. Despite having a completely different color, Indigo Milk Caps are closely related to Saffron Milk Caps, both of which belong to a classification known as Lactarius sect. Deliciosi. One feature present in all types of Milk Caps is that they exude a milky substance when the tissues are damaged. Just a note, not all Milk Caps are considered edible.

While I don’t want to spill the beans before the news gets out, my intel in academia tells me that in the next couple of years, Lactarius indigo will likely be split into several species. This will include very similar but distinct species from Mexico and Central America which currently go under the same name. This isn’t that important though, since they are all edible and practically identical from a culinary standpoint.

One of the biggest mysteries around this mushroom is why it evolved to be so dang blue. Perhaps simply to attract, deter, or effect predators in a certain way? Or maybe the actual pigment of the color is irrelevant, but the chemical properties of it have benefits to the organism. One relevant study did show that extracts of Lactarius indigo do exhibit antibacterial and cytotoxic effects on various strains of harmful bacteria (Ochoa-Zarzosa, 2011), although many more studies are needed to really know what’s up with it. The compound responsible for the blue color has been known to belong to a group of pigments known as Azulenes.

Identifying Lactarius Indigo

As I mentioned before, this mushroom is easy to identify. I mean like really, really, easy to identify. This being said, do your due diligence and double-check if you´re new to foraging mushrooms. There are some toxic purple mushrooms that some adventurous and overconfident beginners could potentially mistake them for. Considering that you´re reading this guide though, you´re probably going to be careful and not going to make that mistake (right?).

The first thing you’ll notice if you have true indigo milk caps is their color. They ́ are not purple or ¨blueish¨, but they are straight-up indigo blue like their name suggests. Sometimes the cap surface may be slightly pale, but once you flip the mushroom you´ll see undoubtedly blue gills.

If you have any doubts, just cut the mushroom. They ooze a milky blue liquid that looks like blue paint and even stains your fingers.

If the mushrooms are old or dried out, they may not have much of this liquid.

The mushrooms themselves are stout with caps that rarely get bigger than 6 inches (15 cm) across, although it’s not unheard of for them to be bigger. They are also seldom taller than they are wide, but stem size can vary. The stem may have small round circular splotches of darker blue, especially towards its base.

Other than just being blue, the cap surface has concentric zonations that spread from the center towards the margin. The shape of the cap is almost always funnel or cup-shaped, with a distinct depression in its center. The cap margin almost always curls down towards the gills, even when the mushroom is mature. The gills are very closely spaced together and relatively brittle if you run your finger across them.

When the mushroom becomes a bit battered you’ll notice a green oxidation which leaves stains on the mushroom. This is easily seen on older specimens that have been tormented by rain or those that have been tumbling around in a bag or basket all day. This is clearly visible in the picture below.

Lactarius indigo always grows directly from the soil, and never from woody debris. They often grow from small clusters of 2 or 3 mushrooms although patches can also be more spread apart. It is not uncommon for them to grow below a bit of dirt or leaf litter which they lift to form ¨shrumps¨.

The outside of the mushroom may be a bit pale, but if you cut through it you´ll see a juicy deep-blue.

Indigo Milk Cap Identification Features

- Cap about 5-15 cm in diameter, usually convex or funnel-shaped. The cap surface has concentric circular zonations and typically has an enrolled margin.

- Color is from dark indigo blue to silver pale-blue in some specimens.

- When cut, the mushroom has dark-blue flesh which exudes a blue milky latex.

- When damaged or old, the mushroom oxidizes green.

- Gills are closely spaced together and relatively brittle.

- The stem is about 2-8 cm in length and 1-2.5 cm in thickness. It is often smaller than the cap diameter, although not always. It may be hollow and have small circular splotches near its base.

- No distinct odor or taste when raw.

- Often grows in clustered patches and always from the soil.

Lactarius Indigo Lookalikes

Anise Seed Funnel (Clitocybe odora)

This is a small blue mushroom that at first sight may look like an Indigo Milk Cap. The main differences are that this mushroom tends to be smaller and it does not have any form of blue-latex. Clitocybe odora also tends to have a lighter-colored and thinner stem which is equal in length to its cap. Lastly, Clitocybe odora also has a sweet anise fragrance.

Blue Woodwax (Hygrophorus caeruleus)

This is a pretty rare mushroom that is only known from mountainous parts of the Pacific Northwest and California fruiting in the spring. It is pretty blue, although it does not have any of the milky-blue latex. The stem is also thicker, denser, and with a stringy almost cotton-like texture. The color of the stem also tends to fade to brown.

Regardless, the range of the Blue Woodwax and Blue Milkcap do not overlap.

Blewit (Lepista nuda)

Blewits are pretty common in forests and woodlands late in the season. They are purple in color and not a true blue. They have no latex and have a fruity fragrant aroma.

They are also edible but should be eaten with the certainty of their lookalikes.

Purple Cortinarius (Cortinarius sp.)

There is a handful of Cortinarius out there which are purple. While some species of these species may be edible, this is a tough group that even experienced mycologists do not consume much of. For all practical purposes, it is recommended to avoid all purple Cortinarius.

These can be recognized by their dark-rusty spores and web-like veil which covers the gills when young. A reminiscence of the web and rusty spores are often visible on the upper part of the stem.

Paradox Milkcap (Lactarius paradoxus)

This is a cool one that I have not seen, but it looks very similar to the Indigo Milkcap and is in fact, closely related. When young this mushroom tends to have a blue color from above, but from below the gills are purple/rose. The color turns a dirty orange/purple as it matures. Unlike the Indigo Milk Cap, this mushroom has a reddish/purple latex and color scheme.

False Indigo Milkcap (Lactarius chelidonium)

Like the Paradox Milkcap, this mushroom looks a lot like the indigo milkcap from above, especially when young. The main difference is that the gills are tan to orange in color, and the mushroom itself can also have a tan-orange coloration as it matures.

Where To Find Lactarius Indigo

Eastern United States: You can find Lactarius indigo in pretty much any Oak or Pine forest in the eastern United States. They occur along the Gulf, throughout Florida, up into the Appalachians, and even along the eastern coastline. They’re also common in the Midwest and along the Great Lakes region.

Canada: In Canada, they are pretty common in the Ottawa and Montreal regions. They have also been reported from remote regions of Saskatchewan although they are not likely common.

Southwestern Sky Islands: Lactarius indigo has been found in montane parts of Arizona in what is known as the ¨Sky Islands¨. This is about as far west as they’ll grow.

Other parts of the world: They are pretty common in montane parts of Mexico, and Central America, and have even been found in northern Columbia. They are also known from Japan, China, and the Himalayan region.

When Is Indigo Milk Cap Season

Northeastern United States and Canada (July to October): Peak season is typically mid-summer to early fall. They can be found as early as June and as late as October-November if conditions are right.

Midwestern United States (July to October): The season here is pretty much the same as in the Northeast.

Southeastern United States (June to October): In the south, the season typically starts a bit sooner than in the north, and can even be spotted as early as May. Likewise, if the conditions allow the season can be prolonged into November although specimens will likely be in bad condition.

Florida (May to December): If you´re lucky, you can find an Indigo Milk Cap any time of the year in Florida. This being said, their peak season tends to be from October to December.

Gulf States (March to December): The Gulf states have a pretty long season ranging from March to December. This being said, their numbers decline greatly during August when there tends to be intense heat and a decline in rainfall.

Arizona Sky Islands (July to September): The season in the Sky Islands is short and sweet, pretty much always peaking in August.

How To Pick Indigo Milk Caps

As I always mention, any foraging should always be done with respect. For the organism which you are harvesting from, but also all the other species in the ecosystem and the local human community as well. Don’t litter, cause erosion, play loud music, or cause any unnecessary havoc. Also, harvest with permission (if necessary) and always leave some behind for other foragers.

Before you even go out, make sure you are properly prepared. I always recommend wearing long sleeves and pants to protect you from spikey brambles, mosquitoes, ticks, and other potentially harmful things you find in the woods. It’s nice to have a pocket knife and something to carry your mushrooms in like a basket. Baskets not only prevent your mushrooms from being damaged during transport, but they are also more effective at allowing the spores to be dispersed as you travel. If you don’t have a basket, a mesh bag also works. Avoid using plastic bags. Finally, if you think you may be out past dark, consider bringing a headlamp with you.

Once you find a patch of Indigo Milk Caps, the first thing I suggest you do is take a look around. Scope the patch and see if there are other clusters of mushrooms hidden below the foliage or somewhere else in the vicinity. If you´re not sure about its identity, harvest a single mushroom to carefully observe its features.

I always recommend folks pick medium-sized mushrooms that are still in good condition. Specimens that are too old just won’t be as tasty, so might as well leave them to complete their natural cycle. Young mushrooms have not released spores nor have they reached their ultimate potential, so it’s best to just leave them behind. If you´re not certain about its identity, just take one with you and confirm it with more resources once you get home.

When it comes to actually harvesting the mushroom, there are two schools of thought. People who cut the mushrooms and those who pluck them with stem-butt and everything. While it´s commonly believed it is best to cut the mushroom for the health of the fungi, the few scientific studies done on this matter suggest there is no difference (Egli, 2006; Norvell, 2016). Some mycologists suggest cutting could negatively affect the health of the mycelium, thus they encourage picking. So, just do you, or do whatever practice is recommended by the local foraging community (to avoid any trouble!).

Even if you pick the mushroom, it’s recommended to cut the dirty end of the stem afterward. You won’t be eating it anyway, and it will just bring dirt into your basket. Remove any excess leaf litter or dirt from the mushroom before putting it in your basket as well. This will go a long way to keeping your harvest clean.

Once you get home, it is ideal to cook your mushrooms that same day or the following one. Unless you have something special planned, there is usually no point in holding onto the mushrooms as they only decline in quality with time. For storage keep them in a well-ventilated place, ideally within a large bowl or paper bag. Never store them in an air-tight container and do not freeze them.

Cooking Indigo Milk Caps

Indigo Milk Caps have an extremely earthy flavor which is loved by some and detested by others. I personally really enjoy the mushroom, but it does have to be cooked right. It’s not like Chanterelles or Hedgehogs which taste good no matter how they’re cooked. From my experience, they´re not their best when simply sauteed in butter with garlic and onions like most mushrooms are.

I enjoy these mushrooms cooked in sauces and broths. I find that when cooked simply with oil or even the famous “dry saute” their brittly texture is not improved by any means. Plus, if they are cooked in a pan with a lot of moisture they tend to retain their impressive blue color. If your mushrooms are a bit dry, it doesn´t hurt to rehydrate them with a bit of water.

My favorite recipe is pretty much ¨a las mexicana¨, which means cooked with onions, tomatoes, serrano pepper, and aromatic herbs. I know a lot of mushroom chefs nay-say cooking mushrooms with tomatoes, but I find that the earthy flavor of Indigo Milk Caps blends well with the umami of a tomato. They can also be cooked in cream sauces or simply added chopped up to a soup. One of my friends enjoys simply boiling the mushroom in salt water, and then dressing it with olive oil, parsley, lemon juice, and more salt. It’s pretty delicious like that too.

I´d say this is a mushroom that is worth experimenting with if you have the chance. If you don’t like it the first time, don´t completely disregard it, but instead try cooking it differently next time.

Preserving Indigo Milk Caps

There are a number of good ways to preserve Indigo Milk caps:

Freezing

Always freeze your mushrooms cooked, as they will not retain their texture if frozen raw. I recommend slicing or cubing the mushroom and then simply cooking it in a pan with 1 to 2 cm of salty water. You can add other seasonings to it as well. Once the mushrooms are cooked, simply let them cool and freeze them with the little bit of broth that is left over. Once frozen, just mix them into any recipe you want.

Pickles

Indigo Milk Caps are pretty good in pickles. Their spongy texture does well in them and does not result in a goey pickle like other species often do. You can make them in either quick-pickles or lacto-fermented, but just make sure to cook the mushroom thoroughly before pickling.

Drying

You can dry the mushrooms, although they won´t rehydrate to their original texture. Dried indigo milk caps are great for broths, or they can be powdered into a mushroom seasoning.

Mushroom Foraging Guides

Looking for more mushroom identification guides?

- Morel Mushrooms

- Chaga Mushrooms

- Birch Polypore

- Tinder Polypore

- Witches Butter Mushrooms

- Puffball Mushrooms

- Shaggy Mane Mushrooms

- Reishi Mushrooms

- Turkey Tail Mushrooms

- Dryad’s Saddle

- Cauliflower Mushrooms

- Yellowfoot Chanterelles

- Saffron Milk Caps