Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

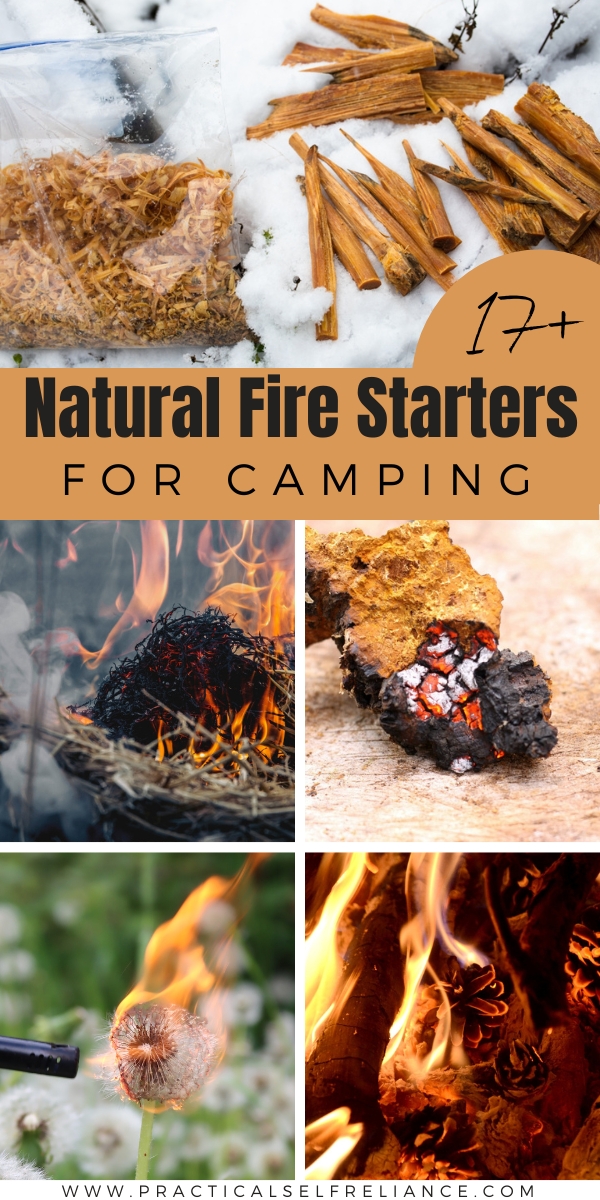

Firestarters are sold in just about every camping and outdoor store, but what did people use before these ready-made options? Natural tinder can be gathered easily enough, and there are plenty of natural firestarters that work just as well (or better) than the storebought versions.

Humans have been building fires with natural resources for thousands of years worldwide. No matter what season or where you live, there are a wide variety of natural resources that you can gather to start fires. Some of these options are great for survival situations, while others are perfect to gather and keep on hand for backyard campfires or starting your woodstove or fireplace.

Here are some of the options that may be available to you:

- Birch Bark

- Pine Fatwood

- Red Cedar Bark

- Pine Cones

- Dandelion Seedhead

- Tinder Fungus

- Birch Polypore

- Chaga

- Cattail Fuzz

- Milkweed Down

- Club Moss Spore

- Dried Grass

- Phragmites

- Bird Nests

- Rodent Nests

- Wood Shavings

- Pine Needles and Leaves

I’ll go over in detail how to find and use each of these below.

Best Natural Firestarters

The ability to easily kindle a fire from natural materials may be essential in a survival situation, but it can also make camping and daily life with a woodstove more enjoyable. Here are some natural fire starters you may find and how to use them.

Birch Bark

Birch bark is one of my favorite natural firestarters because it works even when it’s wet. That’s because it contains a highly flammable, water-resistant compound called betulin.

Paper birch (Betula papyrifera) is probably the most well-known birch for its fire-starting abilities, but other birches like yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), gray birch (Betula populifolia), and river or black birch (Betula nigra) all have flammable bark.

The exact characteristics and habitat of birch depend on your location and the exact species. Generally, birches tend to be small to medium-sized, pioneer species of trees in temperate and boreal forests of the northern hemisphere.

Some species, like the American dwarf birch (Betula glandulosa), rarely reach over ten feet tall, while others, like the paper birch, sometimes reach 130 feet tall. Their habitats can vary just as widely. As the name suggests, the mountain paper birch (Betula cordifolia) is usually found at high elevations, while the bog birch (Betula pumila) usually inhabits swamps and low-lying riparian areas.

It’s best to harvest birch bark only from dead trees. If your options are limited, you can harvest from living trees; just try to take some small strips that are already peeling. Avoid girdling the tree by taking large amounts from around its trunk.

Pine Fatwood

You may have walked right past an excellent firestarter without realizing it inside the stumps of dead pine trees. When a pine dies, whether it falls or is cut, the resin from the roots gets drawn into the stump, usually right near the base. As the roots and outer stump rot, the resin preserves, dries, and hardens this inner wood.

This resin contains an incredibly flammable compound called terpene, which is the main ingredient in turpentine. Due to this, fatwood catches quickly, is resistant to wind, and burns hot and long.

To find fatwood, look for a pine forest or an area where a pine forest has been logged. Look for old, gray, rotting pine stumps. Don’t try fresh stumps; the resin won’t have had enough time to collect.

Collecting the fatwood can be tricky as the best part is generally at in the middle of the base of the stump. If you get lucky, you may find a stump where the wood around the fatwood is nearly or completely rotted making the wood and roots easy to remove.

However, this isn’t always the case; you may need to cut or dig through the wood around the fat wood. Splitting off sections with an axe, hatched, large knife, machete, or froe may be your only option.

You’ll know when you have reached the good stuff because it will be extremely hard and smell strongly of pine resin. It’s usually very resinous and can gunk up your tools. Applying oil or WD40 ahead of time can make cleaning them later easier.

Once you’ve reached the fatwood, try to split it off in small planks about ½ inches wide. A single piece will make excellent kindling by itself. You can also use a knife to create fatwood shavings from one of your planks which will go further and help you catch a coal or spark from more traditional firestarting methods.

Eastern Red Cedar Bark

Though not as famous as birch bark, cedar bark also makes excellent natural tinder. Like many other conifers, cedars contain flammable compounds in their sap and resin. This, paired with their light, fibrous bark, makes for excellent tinder bundles.

However, using cedar bark takes a little more preparation and knowledge than using birch bark. Unlike a birch, where you simply peel the bark off, you want to create a fluffy tinder bundle from cedar bark. To do this, you’ll need a knife or similar tool. Hold the blade to the log at a 90° angle and scrape down the same section several times. You’ll see a fluffy bundle of cedar bark fibers forming at the bottom of the section.

The name cedar refers to several species across North America. Interestingly, the name “cedar” is a misnomer for all of these species and was based on their superficial likeness. None of them are “true cedars,” which belong to the Cedrus genus and are not native to North America.

The eastern red cedar is actually a juniper, Juniperus virginiana. This tree is often a pioneer species but is often spotted in established woodlands as it is long-lived, with the ability to reach 900 years old. Its fibrous root system makes it incredibly drought-tolerant. It will tolerate a wide range of conditions and has an extensive range throughout the eastern and central United States.

It’s best to harvest cedar bark from dead trees. However, you only want to harvest the outer bark, so taking a small section for tinder shouldn’t kill a mature tree. This practice should only be done on private property.

Pine Cones

Pine cones make decent fire starters, especially if they’re dry. If you’re gathering kindling for backyard campfires or your woodstove, you can collect any pine cone you find, stacking them in bins or baskets out of the weather to dry out for later use. If you’re backpacking or need to build a fire immediately, look for dry old pine cones still hanging from branches or those still attached to fallen limbs or trees that are held up off the ground. These will be drier than the ones on the forest floor.

Pine cones generally make the best fire starters for situations where a lighter or match is available. If you’re using a traditional method of firemaking, you’ll want to pair your pine cones with finer tinder, like cattail fluff or cedar bark, to catch your spark or coal. The pine cones will then help you catch larger kindling and wood.

Any species of pine will work. All pine cones contain some amount of terpene a flammable compound that’s the main ingredient in turpentine. This compound allows the cones to catch relatively quickly and to burn hot.

If you live in the northern hemisphere, a pine species probably grows near you. Pine family or Pinus genus members grow in some of the coldest and hottest environments on Earth. For example, scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) is among the hardiest trees, surviving well north of the Arctic Circle. In contrast, the wildfire-resistant longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) thrives in the warm, sandy soils of the southeastern United States.

Dandelion Seedheads

Dandelion seedheads are very flammable. You can easily set one ablaze with a lighter or spark. Unfortunately, they burn up quickly and are tough to get a fire going with alone. If you’re using dandelions to get a fire going, be sure to pair them with other longer-burning tinder like birch bark, small twigs, or fatwood.

Several dandelion species grow across North America, the most widespread being the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale). All species will work as firestarters, and most people know how to find and recognize them. They grow well in sunny, disturbed habitats, including lawns, gardens, pastures, and waste areas, and will tolerate a wide range of soil types.

Tinder Fungus

Long before the advent of modern firestarters, keeping a fire going was usually much easier than starting one, but fire isn’t something you can toss in a bag when you move. Historical humans needed a good way to bring a coal from one place to the next. Enter the tinder fungus or tinder polypore (Fomes fomentarius), an infinitely valuable mushroom with medicinal properties.

This shelf fungus smolders low and slow for several hours, letting you move a campfire from one place to the next. All you need to do is catch an edge on fire from your original campfire.

Tinder fungus is also great for starting fires whether you’re using a lighter, ferro rod, bow drill, or other traditional method. Typically, when we’re starting a fire, rather than safely carrying a coal, we use the fungus a bit differently.

Cut a small chunk off of your tinder fungus and grind it up into a powder using a rock or similar tool. This powder will light easily even from sparks. It burns up fairly quickly so it’s best to set your powder onto a dry leaf which you can then easily transfer to a pile of larger tinder and kindling once it has caught.

We have concrete evidence that humans have used tinder fungus for generations. One example is that the 5,000-year-old mummy in the Alps, dubbed Ötzi the Iceman, carried four pieces of tinder fungus. Researchers concluded that he was using them as tinder.

Usually, you’ll find tinder fungus growing on dead or dying hardwood trees. They cause a type of rot in the tree. They look almost like a horse’s hoof and are usually brown, gray, or almost black.

Birch Polypore

Birch polypore (Fomitopsis betulina) is another medicinal mushroom that functions similarly to the tinder fungus in fire-making. It can be used to carry coals or ground to create a fine, flammable powder. Ötzi the Iceman also carried one of these mushrooms, but researchers concluded that he was probably using it medicinally rather than as tinder.

As its name suggests, you’ll only find these mushrooms growing on birch trees. They’re a parasite on the tree, so you’ll usually find them on dying trees or those already dead. They may continue fruiting on birch logs until the log rots away.

Birch polypores are usually pale with a grayish-tan upper surface and creamy white underside. The young ones are rubbery, but they grow corky with age and become more suitable for starting fires.

Chaga

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus) is a renowned medicinal mushroom, but few people realize it can also be helpful when you need to get a fire going. Like the other fungi on our list, chaga can be used in two ways. A larger chunk of chaga will smolder for hours, allowing you to keep a fire going or move an ember to start a new fire. Dried, powdered chaga will easily catch a spark, acting as a wonderful tinder that allows you to catch larger tinder and kindling using any style of firemaking.

Chaga is a parasitic fungus that usually grows on birch trees but will occasionally infect other species. It looks a bit like a lump of burnt charcoal on the tree’s trunk.

There are some internet articles that claim chaga is rare. However, most reputable sources deny this claim. For example, the Finnish Forest Research Institute reports that 6-30% of birch forests in Sweden and Finland are infected with chaga. That said, it’s always best to harvest respectfully and be mindful of the abundance or lack thereof in your area.

Cattail Fuzz

Well-known by foragers and young children who appreciate the hotdog-shaped seedheads composed of fuzz, cattails (Typha spp.) are another common source of natural firestarter hiding in plain sight.

The fluff or fuzz from the brown cattail seedheads quickly ignites and is a welcome source of tinder in wet areas where they’re common. The fluff can be piled up and lit with a lighter or even just sparks from a Ferro rod and catches quickly. Unfortunately, it also burns up quickly.

If you’re using cattail fuzz as tinder, it’s important to have other, more slow-burning tinder and kindling at hand to catch with the fast-burning fuzz. Dried grass, bird nests, or shredded bark might be good options.

Cattails, also called bullrushes, are herbaceous perennial plants that grow in aquatic or semi-aquatic habitats. Look for them on the silty edges of slow-moving rivers, streams, swamps, ditches, lakes, and ponds.

Milkweed Seed Down

Like the downy seed material of dandelions and cattails, the white seed down or pappus attached to milkweed (Asclepias spp.) seed will go up in a flash with just a few sparks. While it catches easily, its quick burn time means pairing it with slower-burning materials is essential. While it can help you easily catch a spark, you’ll need to feed the flames quickly.

There are many species of milkweed that grow throughout North America. Certain species like desert milkweed (Asclepias subulata) are tolerant of dry climates while others like swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) require moist soil. In general, many of the milkweed species prefer open, sunny areas so you may find them in pastures, roadsides, fields, and prairies.

Generally, I recommend only using milkweed when you have to. Milkweed is a host species for many important insects including the endangered Monarch Butterfly. Leaving their seeds to produce more the next season is usually the best option.

Club Moss Spores

Club moss (Lycopodium spp.) is a lovely little green plant that resembles moss. While it looks unassuming, it has a surprising feature. Club moss spores are highly flammable. They produce such a bright, quick flash that photographers used them as flash powder before the advent of flash bulbs. Today, club moss spores are still sometimes featured in special effects, fireworks, and magic tricks!

Unfortunately, as club moss spores burn up so quickly they can be difficult to light a fire with. You’ll need to combine them with other highly flammable materials like some of the options mentioned on this list.

There are many species of club moss. Many species grow in moist, acidic, low woodlands, bogs, and wet prairies, but some species will tolerate drier woodlands, too. They’re fairly common, easy to find, and look like moss or miniature conifers growing on the forest floor.

You’ll need to find club moss at the right time to collect spores. Watch for spore-bearing heads called sori that form on the tops of the club moss. When these spore heads turn dark yellow or brown, they’re ripe. At this time, you can gently tap these heads over a leaf or piece of paper to collect the spores.

Dried Grass

Grass is available worldwide, and throughout much of the year, it’s fairly easy to find patches of tall, dry grass. Sometimes, it even sticks above the snow. One of the best features of dried grass for firemaking is its flexibility. It’s easy to twist and form into bird-nest-shaped cups to hold other flammable material like cattail fluff and catch sparks or coals. While it may not burst into flame quickly on its own, it can be indispensable when combined with other materials.

Don’t try to use grass that is lying on the ground or has been cut green, like grass clippings from a lawn mower. These will be too wet to light.

Phragmites

Phragmites are a genus of perennial reed grasses. These plants live in aquatic habitats similar to cattails and produce large, feathery, brown-plumed seed heads, usually in late summer or fall. Like cattail seed heads, these plumes are highly flammable, but they may be a bit more effective than cattails. Phragmites seed heads generally have longer burn times than cattail seed heads and other similar materials while still being easy to catch.

Watch for phragmites growing in slow-moving or still waters on the edges of lakes, ponds, rivers, streams, swamps, and wetlands. They often form large colonies, blocking out other plants and making it easy to collect enough material to build a fire.

Old Bird Nests

Depending on the type, old bird nests are ideal, ready-made tinder bundles, especially for those trying to catch a coal using traditional fire-making skills. In fact, you’ll sometimes hear folks practicing skills like bow drill fires refer to their tinder bundles as bird’s nests. They make a depression in the center of dried material to catch a coal.

Look for nests that are dry and constructed from fine materials. Those made with mud and heavier twigs will not work as well as those with dried grasses, plant fibers, and tiny twigs.

It goes without saying that you should only use bird nests that you’re certain are empty. Many birds abandon nests after a single season, so it’s not unusual to find uninhabited ones. Some birds even create several fake nests around their real one to throw off predators. If you’re uncertain, watch the nest for a few moments before approaching to observe any activity, like birds coming in with materials or feeding young.

Old Rodent Nests

Similarly to birds, rodents like mice and voles, as well as squirrles, make nests of soft, dry material. Like bird nests, these can be ready-made firestarters if you stumble across one. Generally, they’re hidden underground, in old logs, tree hollows or in other places that provide cover, like brush piles, old boards, logs, tangled plant growth, and discarded metal.

As with bird nests, you want to watch for any signs that animals are still actively using the nest before removing it.

Wood Shavings

Twigs can be tough to catch even with a lighter and near impossible with traditional firemaking methods. Thankfully, with a knife, you can create thin shavings that will catch from a single spark. Push your knife down a stick with the blade pointing away from you to create thin shavings. If it has been raining you can shave off and discard the damp outer layer before piling the inner dry shavings.

Shavings from resinous trees like pines, cedar, and spruces can be especially easy to light. Look for dead material that has remained off the ground.

Pine Needles and Leaves

Dry brown leaves and pine needles can both provide tinder to start a fire. Gently gather the top layer off the forest floor. The material beneath will likely be too damp to light. If you get lucky, you may also find material that has been held off the ground.

These materials are great if you have a lighter or work well in combination with dry wood shavings, cattail fluff, tinder fungus powder, or other quick-burning materials to help you catch a spark.

Camping & Outdoor Living

Looking for more camping and outdoor living ideas?