Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

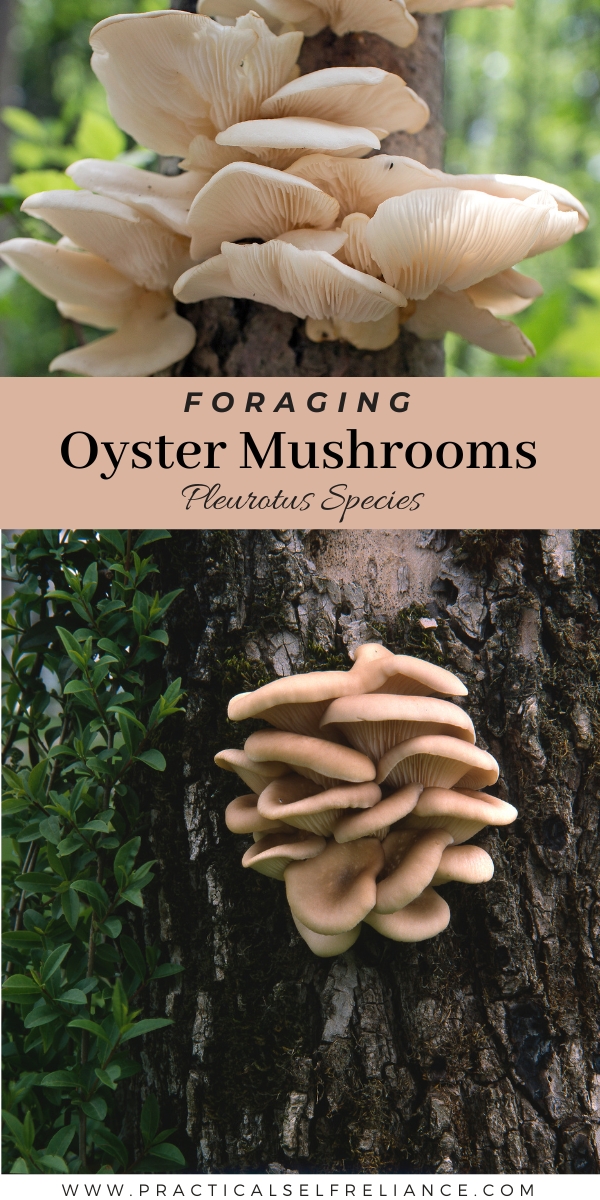

Oyster Mushrooms are some of the most well-known gourmet edible mushrooms out there. You can often find cultivated varieties in grocery stores, and almost always at your local farmers market. This being said, with a keen eye and a bit of enthusiasm can also easily find them in the wild. They are some of the most widely spread and adaptable mushrooms, so no matter where you live, there is likely a local variety that appears when conditions are ripe.

This article was written by Timo Mendez, a freelance writer and amateur mycologist who has foraged wild mushrooms all over the world.

Oyster Mushrooms are also a great choice for beginner foragers because they’re widespread and have few toxic look-alikes. With just a bit of due diligence, anyone can recognize them safely and collect them. In this article we will be discussing everything you need to know to find, identify, forage, and cook wild oyster mushrooms.

Natural History Of Oyster Mushrooms

Oyster Mushrooms are wood decomposers that are often found growing from large-woody debris. This can be branches, stumps, stems, logs, and even milled wood. While most of us only ever see the mushroom fruiting bodies, the fungus itself lives within this woody debris as mycellium. The mycellium exudes enzymes, breaks down the wood, and consumes it as a food source.

More often than not, Oysters grow from hardwoods like Oak, Beech, Chestnut, Walnut, and alder. While they do have preferences for these sorts of tree species, they can be found growing with almost anything. They are even occasionally found on coniferous woods, but this is pretty rare.

If you’ve ever seen Oyster Mushrooms at a farmer’s market, then you probably know there are many different varieties of them out there. In the wild, there are more than 25 species, some of which have been cultivated and even domesticated into unique cultivars. While Oyster Mushrooms across the board tend to have many of the same diagnostic features, certain species are pretty distinct, so learning your local varieties can be pretty helpful. I´ll talk about some of the most common varieties in the identification section of this text.

Where To Find Oyster Mushrooms

Oyster Mushrooms can be found almost anywhere there is large woody debris present. This can be a temperate forest, tropical jungle, and even a desert-like ecosystem. Almost every region has its unique variety with distinct host preferences. This being said they tend to almost always prefer hardwood trees and avoid conifers. In temperate climates, some of the most common hosts include Oaks, Chestnuts, Walnut, Alder, Laurels, and many other tree species. This being said, Oak tends to be one of the favorites.

To find Oysters, it’s important to keep your eyes open for large woody debris that could host the fungus. Large fallen trunks and branches tend to be great habitats, as well as stumps. In some cases, a large flush of Oyster Mushrooms can be easily visible from a distance, but in others, you may need to approach any suspected habitat and take a closer look. Once you recognize the most important host trees in your region, you should try to focus your search on areas with higher densities of these trees.

Realistically, few people go to the woods solely looking for Oysters. Their season can coincide with that of many other different mushroom species including Chanterelles, Black Trumpets, Lobsters, Chicken Of The Woods, and many more. For many foragers, Oysters are simply considered an additional bonus to the more sought-after gourmet species. Some foragers might only harvest Oysters when there isn’t much else to harvest.

When To Forage Oyster Mushrooms

Oyster Mushrooms are extremely opportunistic fruiterers and will pretty much appear whenever the conditions are right. These conditions tend to occur during the rainy season when there is plenty of moisture. Certain varieties might appear during summer when temperatures are high, while others prefer the cool temperatures of fall and winter. If you get a good off-season rain, this can also be enough to trigger the fruiting of Oyster Mushrooms.

Peak Season For Oyster Mushrooms

- California: October to February

- Pacific Northwest: April to June and September to November

- Southwestern Sky Islands: July to September

- Gulf States: September To February

- Southeastern United States: July to February

- Midwestern United States: May to October

- Northwestern United States: June To October

Identifying Oyster Mushrooms

Oyster Mushrooms are pretty straightforward to identify and just require a bit of due diligence to ensure the validity of your harvest.

The first thing you´ll notice about Oyster Mushrooms is that they grow directly from some sort of woody debris. They´re not growing from dirt, manure, or any other type of substrate. Occasionally, Oyster Mushrooms will even grow from rotting wood within homes and other forms of human infrastructure. They can also appear to grow from the soil if there are large pieces of woody debris buried.

The second thing you’ll want to pay attention to is the color. While the most common species are completely white or with a gray cap, others can be yellow, brown, or even pink.

Other than the pink oyster, all other species have white gills and stems. The cap surface is always smooth.

After this, it is important to take note of the general form of the mushroom. Oyster Mushrooms tend almost always to grow in clusters that have at least 3-4 mushrooms in a clump. They can grow individually, but this tend to be only a few mushrooms in a patch.

Oyster Mushrooms also have an angled stem that is typically off-center from the mushroom cap.

One of the most important identification features is the tightly packed “decurrent” gills. Deccurent refers to the fact that the gills run seamlessly down the bottom of the cap and onto the stem. They do not have a distinct cap or stem, but they kind of fuse together. This being said, they should always have a stem, even if it’s just a couple of millimeters in length. The cap shape is often semi-circular, kidney, or shell-shaped. The cap margin is enrolled when young and often unfolds as it matures.

Oysters have a distinct smell that is often compared to seafood. While I don’t necessarily agree with this description, it’s hard to compare it to anything else. Store-bought Oyster Mushrooms have the same smell.

When the mushrooms get old they often become fragile, dainty, and even partially translucent. In some cases, Oyster Mushrooms will completely dry up on the log. When they dry like this, they turn into a pale yellow coloring. Naturally dried oysters like this can often still be good to eat.

Oyster Mushroom Identification Checklist

- Always growing directly from woody debris.

- Color is typically white to pale gray, but it can vary.

- They typically occur in clusters of at least 3-4 mushrooms.

- The stem is angled and usually off-center from the cap. Stem should be at least a couple of millimeters in size.

- The gills are tightly packed and decurrent, meaning they seamlessly run down the cap and stem.

- The margin is enrolled when young and unfolds as it matures.

- They have a distinct “Oyster Mushroom” smell.

Common Varieties Of Oyster Mushrooms

There are lots of different oyster mushrooms, but these are some of the most common to find in the wild:

Common Oysters (Pleurotus ostreatus)

The most common oyster is either completely white or a bit tan to gray on its cap surface. Like many Latin names, Pleurotus ostreatus is widely used for a handful of distinct species.

Pale Oyster (Pleurotus pulmonarius)

This is very similar to the common oyster, but much lighter in color. These often have nice large stems and tend to prefer warmer temperatures.

Golden Oyster (Pleurotus citrinopileatus)

This is a beautiful oyster mushroom with a brilliant yellow-colored cap. It is invasive to the eastern United States and is believed to be harmful to fungal biodiversity.

Aspen Oyster (Pleurotus populinus)

Very similar to other Oysters with a pale to brown cap, but distinguished by its growth on Aspen, Cottonwood, and other Populus species. Usually fruits in late spring and summer.

Lynx Paw Oyster (Pleurotus levis)

These oysters are pale in color and distinguished by the large chunky stems. It also has a partial veil.

Veiled Oyster (Pleurotus dryinus)

This species looks pretty similar to the common Oyster Mushroom but it has a partial veil that covers the gills when young. This eventually breaks and leaves a bit of remanence on the stem which can be used for proper identification.

King Trumpet (Pleurotus eryngii)

This species can be a bit more difficult to identify since it has a large stem and a more typical stem-cap shape compared to other Oyster species.

Other Notable Oyster Mushroom Species

- Pink Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus djamor)

- Brown Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus australis)

- Branching Oyster (Pleurotus cornucopiae)

- Pleurotus calyptratus

- Pleurotus albidus

- Pleurotus tuber-regium

- Pleurotus parsonsiae

- Pleurotus opuntiae

- Pleurotus giganteus

- Abalone Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus cystidiosus)

- Pleurotus smithii

- Blue Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus columbinus)

- Pleurotus abieticola

- Pleurotus floridanus

- Pleurotus eugrammus

- Pleurotus agaves

- Pleurotus magnificus

- White Ferula Mushroom (Pleurotus nebrodensis)

- Pleurotus ostreatoroseus

- Pleurotus fuscosquamulosus

Oyster Mushroom Lookalikes

There are a few different species that look like Oyster Mushrooms, but they’re all pretty easy to distinguish. Thankfully, none of them are known to be very toxic.

Oysterlings (Crepidotus sp.)

These are small oyster-like mushrooms that are typically white. They can be distinguished by their small size (just a couple of cm in width) and the lack of a distinct stem. Sometimes the stem is just a miniature little nub, if present at all. Certain Oysterlings also have a fuzzy cap texture.

Bitter Oyster (Panellus sp.)

These mushrooms look similar to Oysters but they tend to be a dingy brown color. They also do not have decurrent gills, meaning that the gills do not run down the stem but have distinct zonation. Bitter Oysters are also thin and much tougher than regular Oysters. As the name implies, these mushrooms also have a bitter flavor. Some Panellus species glow in the dark!

Angel Wings (Pleurocybella porrigens)

Angel Wings look a lot like Oyster Mushrooms and differentiating them can be difficult for beginners. To begin with, they are always completely white. They never have a distinct cap color but their coloration is uniform. This can make them difficult to differentiate from white oyster varieties, although they tend to be even lighter in color.

The second distinct feature is that Angel Wings have a significant concave structure when they mature. They look a bit folded, similar to a taco shell. Oysters tend to be flatter in shape, although they can be mildly concave.

There is some fear around consuming this mushroom due to some fatal intoxications that happened in Japan associated with this mushroom. The exact reason for this is not exactly well known, considering that it is traditionally valued as an edible mushroom in parts of Asia. While I think it’s important to exert caution, consider that poisonings related to this mushroom are unheard of outside of the few cases in Japan.

How To Harvest Oyster Mushrooms

Always harvest mushrooms with respect for the organism and the ecosystem in which they live. Avoid causing erosion or any unnecessary disturbance, and always leave the woods cleaner than when you entered them. Also, be respectful towards locals who utilize the forests for exercise, recreation, and other resources.

Once you find a patch of Oyster Mushrooms take time to observe it. Check the entirety of the log/stump/trunk to get a better idea of how big the patch is and how much you should harvest. I always recommend folks should only harvest the best specimens of the patch. These will handle transportation, storage, and generally be a more enjoyable culinary experience. Perfect specimens will be firm, and dense, and won’t have an upturned cap margin.

Old specimens can be buggy and they might not even last too long in your basket before shattering into pieces. It’s also recommended to leave any small mushrooms less than 3-4 cm in size. Since most patches have mushrooms at various life stages, you will always leave plenty behind if you only take prime ones.

When it comes to harvesting there are generally two schools of thought. Some folks like to pick them, stem and all, while others prefer cutting them. While there’s only been limited research on this subject, the consensus of the studies suggests there is no major difference. Many well-versed mycologists suggest that picking is better for the organism, as you do not leave any rotting mushroom tissues behind which could propagate pests or disease. This is the practice also typically done by mushroom growers.

Regardless of your preferred method, I always urge foragers to clean their mushrooms before placing them in your bag or basket. This will keep your mushrooms much cleaner in the long run, as the dirt/duff won’t be rubbing off one mushroom and into another one. For Oysters, this typically just means removing the stem-butt.

Once you harvest your mushrooms it’s important to carefully transport them through the woods and to your home. Certain Oyster Mushroom varieties can be a bit fragile and if you’re not careful, they’ll be a mush before you get a chance to cook them. Baskets and boxes are recommended for this reason.

Cooking With Oyster Mushrooms

There are countless different ways to cook Oyster Mushrooms. They’re very meaty and can be easily incorporated into so many different recipes. Honestly, they’ll pretty much taste delicious with anything you add them to.

My favorite way to incorporate them into a dish is to simply saute them with a bit of oil and garlic until they’re golden brown. Salt and pepper to taste. If they’re very wet, you may want to start with a dry sautee before adding oil. Once you have these delicious morsels cooked up, simply use them to garnish any dish you’re making. Pasta, pizza, stir-fries, salads, curry, and almost any savory meal will be improved with a bit of Oyster Mushrooms on top. I really enjoy sauteed oysters in salads.

Another one of my favorites is breaded oysters. Simply put your cleaned oysters in an egg wash and then tap them down with flour or bread crumbs. You can either cook these in a pan with a bit of oil or simply drizzle them with oil and throw them in the oven. These are not only delicious but kids love them too. They’re the so-called “Chicken Nuggets Of The Woods”. You can also use these breaded Oyster Mushrooms to make a delicious sandwich.

If I have a large cluster of Oyster Mushrooms, I also like to make meaty Oyster Mushroom steaks. To do this, I simply take the entire cluster and saute it whole in a pan with a bit of oil. Add salt, pepper, red chili flakes, and whatever other seasoning you’re craving. Keep a lid on the pan while you’re cooking to make sure it gets well steamed. Cook on both sides until golden brown. Serve this with sauces of your choice and enjoy.

Occasionally, I also like to prepare Oyster Mushrooms for vegetarian sushi. To do this I cook them in a sweet marinade with soy sauce, sugar, sesame seeds, sesame seed oil, rice wine vinegar, ginger, and garlic. Once cooked, I let them cool down and add them to a sushi roll with other ingredients of choice.

Medicinal Properties Of Oyster Mushrooms

While Oyster Mushrooms aren’t typically considered medicinal mushrooms, they have been well-studied for their medicinal properties. Like many other species, they are believed to help improve immune health and may potentially help regulate cholesterol and blood sugar levels.

Preserving Oyster Mushrooms

There are many ways to preserve Oyster Mushrooms, each with distinct benefits.

Dehydrated: Dehydrated oysters don’t necessarily retain their texture, but they have awesome flavor. I love adding them to soups and sauces.

Cooked and Frozen: Cooking and freezing is one of the best ways to store mushrooms if you have a bit of freezer space. Just saute or steam them, add seasoning if you wish, then plop them in the freezer. Once thawed, they’ll practically be as though they were just freshly cooked! Don’t freeze fresh mushrooms as they’ll turn into a gooey mush that won’t be so appetizing.

Jerky: Oyster Mushroom Jerky can be made by marinating and cooking your Oyster Mushrooms before dehydrating. I like to make a marinade with soy sauce, BBQ sauce, chili flakes, and a bit of salt, but feel free to be creative. Once cooked in its marinade, put them in a dehydrator for 6-12 hours. Like this, they’ll turn into delicious chewy jerky snacks!

Mushroom Foraging Ideas

Looking for more mushrooms to forage this season?