Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

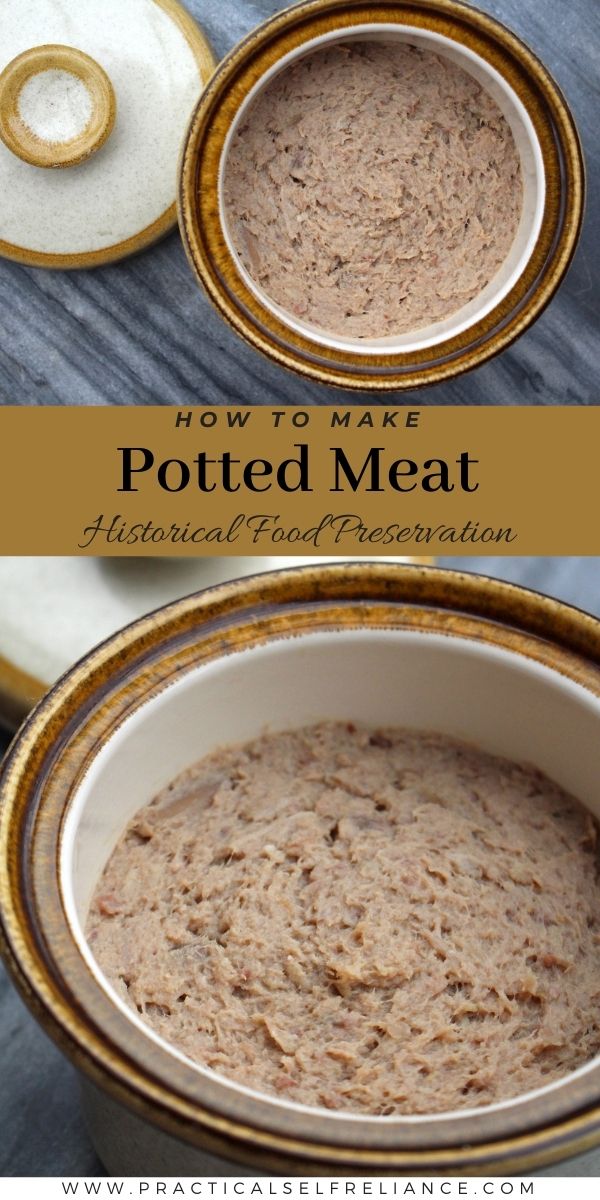

Potted meat is a historical form of food preservation that’s still used in many parts of the world today. Meat is carefully cooked and then sealed with fat or butter, and then stored for many months at a time without spoilage.

If you’ve read my writing for any length of time, you know that I’m a huge nerd for historical food preservation methods. I’m especially attracted to those that are not only effective but delicious, and potted meat fits that bill wonderfully.

Like traditional charcuterie, potting is no longer necessary from a strict food preservation standpoint. However, it’s still practiced because the results are incredibly delicious, even if you don’t use it as a food preservation method.

The French duck confit and rillettes are both examples of potted meats that would have been prepared by peasants and then stored for months at a time. These days, they’re just made at fancy restaurants and served to that night’s high-paying customers.

It’s not just high-end restaurants that keep the practice alive. My dad told me stories about my great-grandmother keeping potted sausages in the cellar all winter during his childhood in the 1960s, and that tradition came was passed down for generations.

The practice of potting meat goes back millennia, and just about every culture that has a climate suitable for root cellaring has some form of traditional potted meat.

(Historical potted meat is different from the modern canned “potted meat” that is basically a horrible tasting slimy meat puree packed into tin and canned using an industrial process. It has the same name and, in theory, has a similar culinary origin, but that’s like saying spam and prosciutto are the same things. Both meat, but very different, obviously.)

What is Potted Meat?

Potted meat is both a cooking method and a traditional method of meat preservation before refrigeration. Recipes vary, but generally, meat is slow-cooked for many hours, in either it’s own fat (as with fatty animals like duck or goose) or a rich stock (beef, lamb, etc).

It’s in a tightly sealed container, and it’s basically slow cooking to tender perfection while sterilizing the contents of the pot at the same time. The cooking method either results in a layer of fat on top that seals the container, or a layer of melted butter or fat is added at the end.

The fat serves to block out air and contaminants, extending the shelf life of potted meat.

Besides the name “potted meat,” recipes sometimes call it “jugged meat” or “jugging.” When the meat is cooked in fat instead of stock, it’s called confit.

How Does Potting Preserve Meat?

While it’s commonly believed that potting meat is a way to preserve meat without refrigeration, that’s not strictly true. It’s a way to preserve meat BEFORE electric refrigeration, but it doesn’t preserve meat at room temperature. (Or, at least not for long.)

Elizabeth Luard writes about this in her book The Barricaded Larder,

“Potted meat and fish preparations…are common to the northern countries whose climate, until the advent of centrally heated kitchens, allowed lengthy storage in reasonably cold temperatures. The refrigerator and freezer offer the modern alternatives to our grandmother’s larder, which had only a wire mesh between it and the outside elements. We owe, in some measure, our highly developed chemical preservatives to the industry of central heating.”

This is true of many traditional food preservation techniques, including jams and jellies, before the advent of canning. Realize that when you try to recreate your grandmother’s (or great-grandmother’s) preserves, it’s likely they won’t keep in your well-heated modern home.

While these preserves don’t technically require a refrigerator, they do still require refrigeration, and that was accomplished historically with a root cellar or spring house, or something similar.

That’s not to say these are not preserved. If kept cold, potted meats will keep for many months. Both raw and regularly cooked meats will spoil much faster in similar conditions.

Botulism and Potted Meat

One thing that’s incredibly important to note is the risk of botulism if potted meat is not prepared and stored correctly. Botulism is deadly serious and incredibly nasty, so nothing to toy with.

Botulism is a toxin that is produced when something contaminated with its spores is put into the right conditions. Botulism spores are everywhere, especially in soil, so they’re hard to avoid.

The thing is, botulism spores are harmless as is. They only thrive in the right conditions, producing what’s known as botulism toxin.

You’re at risk anytime you have low-acid food (meat, vegetables, etc.) kept in anaerobic conditions (without oxygen) without refrigeration. Specifically:

- warm (above 40 degrees F, or about 4 C)

- low acid (pH above 4.6)

- anaerobic environment (without oxygen)

Botulism spores can live through boiling temperatures, and they’re not destroyed until temps reach 240 degrees F (115 C).

That’s one reason pressure canning is the main method used today to make meats and vegetables shelf stable. Inside a pressure canner, temperatures exceed 240 F, which means that you can store home-canned meat right on the pantry shelf (instead of the cold cellar).

These days, botulism poisoning is usually the result of improperly canned food, both commercially made and home canned. Canning meat and canning vegetables, for example, both require a pressure canner to eliminate the risk of botulism.

Historically, people limited the risk of botulism by keeping the food cold (under 40 degrees) in storage. That’s obviously harder to maintain consistency without modern refrigeration.

Beyond that, they avoided including ingredients that had soil contact, like root vegetables, onions, and garlic. Those are much more likely to harbor botulism spores. The meat itself, if kept impeccably clean, is relatively unlikely to have botulism spores present.

Sometimes recipes for potted meats include curing salts or nitrites, which is what keeps salami and dry-cured meats from harboring botulism. In the right proportions, curing salts are an effective way to prevent botulism and will allow potted meats to be stored more safely.

Lastly, potted meats were often (but not always) cooked before they were served. While botulism spores can survive high temperatures, the actual botulism toxin they produce cannot.

Botulism toxin is destroyed by boiling temperatures, and foods were simmered for at least 10 minutes to both reheat them thoroughly and destroy any botulism toxin that may have been present.

When not cooked, potted meats were only stored for short periods of time (1-2 weeks), and usually prepared in the coldest part of the year. It was a lot easier to make sure that the cold room was cold over the short time they were in there.

Do not attempt to make these recipes and then casually store them at room temperature for months at a time. That’s not their intended use, and it’s a recipe for disaster.

These are food preservation techniques from before dependable electric refrigeration…but that doesn’t mean room temperature, it just means using ingenuity to keep things cool.

How to Make Potted Meat

The basic process for making potted meat starts with first salting, then slow-cooking meat in fat for several hours, or over the course of a whole day.

That alone renders the meat tender, rich and succulent, and it’s a truly delicious way to prepare meat in any case (regardless of whether or not you need to preserve it).

Generally, all blood vessels and gristle were removed, but the bones were often left intact in the crock. (Especially when working with poultry.)

The meat is then removed from the cooking fat. With duck confit, it’s carefully packed into a crock whole, but other potted meats often remove the bones and then pound the meat (as with rillettes).

The drippings are either drained and completely removed from the crock, or less commonly, they’re drained and then rapidly boiled to concentrate them into a hearty bone broth that will gel and solidify in the crock.

Clarified fat, either carefully rendered lard or clarified butter, is then added to seal the crock. If the meat was pounded, then it’s pounded with the fat so that each piece is thoroughly emulsified into the fat.

Either way, the crock is filled until there’s at least a 1/4 inch of fat covering the meat at the top of the crock (some sources say at least a full inch). It’s then chilled so that the fat solidifies and seals the meat for preservation.

That’s the basic process, but each culture has its own specific traditions. As I mentioned, sometimes curing salts are used, which is a more effective botulism preventative than a cold cellar alone.

Sometimes specific packing instructions are part of the process, and other times everything is placed in the crock ad hock. It really depends on the type of meat being preserved and the cultural expectations around how it will be served (cold vs. warmed, etc.).

Potted Meat Recipes

Many different types of meat were potted historically, and many of these practices are still in use today.

Lamb and fish are popular in the Nordics, while duck, goose, and pork are most common in France and Western Europe. The British Isles are known for potted beef, and there are even cultures with potted shellfish and organ meats.

Cheese is also traditionally potted using similar methods.

Potted Beef

The video below comes from Townsend’s, which makes historical videos about the early colonial era in the US. They cover everything from clothing to historical food preservation.

In this video, they’re taking you through a recipe for potted beef from Charlotte Mason’s A Lady’s Assistant from 1777. It’s a very simple recipe for potted beef, perfect for beginners.

Potted Mutton and Lamb

While beef is popular in Britain and the colonies, mutton and lamb are popular potted meats in the Nordics. The Nordic Cookbook has a recipe for a potted mutton neck that slow cooks the bone in meat all day, with just a few spices.

White pepper, whole mustard, allspice, and bay leaves give the meat a really wonderful flavor. The bone-in cooking method ensures a nice rich stock that gels easily, and slow cooking means the meat is melt-in-your-mouth tender.

Just slow-cook the meat in a bit of broth for 12 to 15 hours. It’ll encase itself in a rich gelatinous broth that will solidify when cooled, and the natural fats will float to the top to seal the container. (Or, you can top with clarified butter or lard to make sure you get a good seal before storing.)

We actually made this recipe, and it was unbelievable.

Potted Chicken, Duck, and Goose

Poultry is generally potted in fat rather than stock, and a slow cook in fat yields incredibly tender, succulent meat.

Historically, goose and duck were popular choices because they naturally contain enough fat to preserve themselves. Chicken is a leaner meat, and you’ll need to render fat from several birds if you’re potting a single chicken.

Regardless of the bird, the recipe is the same, and here’s where I walk you through the process for traditional potted poultry.

Potted Pork and Sausage

Since pork is a fatty meat, it’s often made confit style and preserved in fat. Adding lard to the pot and then slow cooking will yield tender meat, and the crock will seal with fat when it cools.

I made a confit of pig feet using a traditional recipe, which is unbelievably tender.

Potted Fish, Shellfish, and Roe

The Townsends also put together another video covering potted salmon, but this method could be used with any type of fish. They mention that a type of freshwater fish called Char was especially popular in the era.

The recipe comes from Mrs. Frasier’s The Practice of Cookery from 1791.

One last reminder…all of these are historical food preservation methods that do require cold storage, even if they’re methods from “before electrical refrigeration.”

If you attempt these, they will need to be kept in your refrigerator…but they should keep much longer than just plain leftovers would. Weeks, or potentially months, if prepared properly.

Further Reading on Potting Meat

I’ll admit that resources that thoroughly describe historical food preservation techniques are hard to come by these days, and it took me quite a while to research this topic.

There are a few truly excellent books that cover potting meat and other food preservation methods, and these are all excellent sources:

- The Barricaded Larder by Elizabeth Luard

- European Peasant Cookery by Elizabeth Luard

- The Nordic Cookbook by Marcus Nilsson

- Stocking Up by Carol Hupping

- Preserving Food without Freezing or Canning

Food Preservation Tutorials

Looking for more food preservation tutorials?

- How to Make Apple Cider Vinegar

- Beginner’s Guide to Cheesemaking

- Beginner’s Guide to Water Bath Canning

- Beginner’s Guide to Lacto-fermentation

- How to Make Beer at Home

- How to Make Mead (Honey Wine)

Thank you for this article; some of the info you provided re things like boiling after potting to kill botulinum toxin, I have not found anywhere else, so it was extremely useful; in fact your entire botulism section was great; thank you!

You’re very welcome. We’re so glad it was helpful.

I’d like to add to your list of British potted meats the following which are the most famous here: potted shrimps and jugged hare. Whilst hare is no longer a common dish, I can attest to the deliciousness of East Anglian potted shrimps!!

Thank you so much for sharing that. It sounds like something to try.

Fascinating stuff. Great research. Very much appreciate what you do.

Pam from Vermont

Thanks Pam!

Thank you so much for such an excellent article! I was trying to research this topic myself last year and was not able to find much at all – now I feel much more prepared to do potted meat safely. I really appreciate your work and depth of research

You’re quite welcome!

These recipes sound pretty tasty!

Hi, Ashley! What an awesome resource you are, and what an amazing list of additional ones! Thank you! I am curious about ways to use the potted meats, particularly the pulverized ones. Hubby is a retired personal chef, and occasionally makes a double batch of confit, we eat what we want, divide the rest, stashing some in the back of the fridge, for several weeks or even longer, while keeping the rest closer to the front, to finish off in the next few days.

When we do ham, I’ll often grind the leftovers(or at least some) to make a lovely deviled ham salad that we eat on sandwiches, as part of a leafy green salad, or even as a dip, with crudites & or crackers. It’s a very nice change of pace, from hunks of meat, but I’m not sure how well it would translate to the rest of our meats, and I’m pretty sure it would get tiresome, after a while, with only those serving methods. How do you use your own potted meats? Do you know of other ways to eat them?

I think we’re just gluttons…and I’ve only once or twice had leftover duck confit to make rillettes. We tend to just go crazy with it when it’s just cooked, and both my kids love it too. I actually usually do two ducks at a time just so there’s enough to go around, and then we serve it with something light like a salad.

Since most of these preservation methods are for preserving leftover cooked meat, ideally in small pots, you should have more like single serving amounts which we just eat on fresh baked bread, and sometimes we pull out some pickles or prepared horseradish to go with it. Not all that creative, but it’s a great lunch.

The salmon makes great sandwiches, especially with lettuce and a bit of dill if it’s in season in the summer months. Add an avocado and it’s perfect. Kinda like a tuna sandwich, but much better.

The beef we’ve used to make homemade taquitos, which are actually pretty easy, and all you need is corn tortillas, seasonings and the potted beef. You can use the fat on top for frying them.

On, YUM!! Thank you! (And thank you for such a quick response!) Our stove died right before the holidays (while I was canning), at about the same time that we had to do a small fortune on a new woodstove & installation. We’re still recovering and researching new stoves, so we’re cooking on the woodstove & a camp stove, and canning anything is pretty problematic, right now – and we just bought a whole hog from our neighbor. So, this post is VERY timely, for us. Thank you so MUCH!!

Great article. I’m also a fan of Townsend’s, and love the videos. I clicked your link for Elizabeth’s books, and I noticed her last name is spelled Luard. Perhaps your spell checker corrected the spelling when you weren’t looking, they’re whimsical that way.

Another book that you may wish to consider making room on your bookshelf for is “Home Production of Quality Meats and Sausages”, by Stanley Marianski and Adam Marianski. It’s 707 pages. Looks like I’ll be planning another project this year by constructing the necessary work areas for some tasty meats. Search for Stanley Marianski’s name on Amazon and you’ll find many books on making good eats.

Thank you for catching that, I’ve just gone in and corrected it.

I absolutely love everything by Stanley Marianski, and I think at this point I have all of his books…including the one you mention. He really knows his stuff!