Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Saffron milk caps are a mushroom species complex, made up of many different edible mushrooms found around the world. They all have similar identification characteristics, and they’re quite delicious. Many are used in traditional cuisines throughout Europe, especially in Spain, but they’re also popular in other parts of the world.

This article was written by Timo Mendez, a freelance writer and amateur mycologist who has foraged wild mushrooms all over the world.

The Saffron Milk Cap, known scientifically as Lactarius deliciosus, was originally described in 1753 by the father of taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus. While he had the honor of naming a plethora of mushrooms, including Chanterelles, King Boletes, and Hedgehogs, only the Saffron Milk Cap was privileged with a name meaning delicious. While we don’t know too much about his gastronomic interests, it wouldn’t be far-fetched to think these were likely some of his favorite mushrooms.

While they aren’t exactly revered in the United States, in many different parts of the world people absolutely adore them. During mushroom season in Barcelona for example, every produce store you walk into proudly displays their box of fresh milk caps. Sometimes they place them at the entrance of the store to tempt customers in; other times they place them next to the cash register to entice a last-minute craving during your purchase. Known as Robellon (in Catalonia) or Niscalo (in the rest of the country), they are by far the most popular mushroom in all of Spain.

Various forms of Saffron Milk Caps are also readily enjoyed in Poland, France, the Czech Republic, Italy, Mexico, and almost any mushroom-loving culture on the planet. And, while they readily occur in almost every mushroom-producing region of the United States, many seasoned foragers show no interest in them. You never see them in markets or specialty produce stores that carry other wild mushrooms.

While I don’t think anyone has done a proper analysis of why this is, there are probably at least two reasons why I think this is the case.

The first is purely a cultural thing. Milk Caps are often considered to have a granular texture; some even consider them mealy. And it’s kind of true. They have a brittle, spongy texture that is not familiar to the American palette. In the United States, the most appreciated mushrooms are those with a meat-like texture, not the squishy, spongy, or slimy.

The second is more related to the nature of the mushroom itself. The truth is, you don’t get the same species in North America as you do in Europe. Even if the field guides on both sides of the “pond” say Lactarius deliciosus, it’s well known that this name encompasses a group of yet-to-be-described species. That’s why they’re sometimes referred to as the Lactarius deliciosus complex.

In fact, even within Europe, there are different species of “Saffron Milk Caps” which are close to indistinguishable. Some of them are delicious, while others have subpar to mediocre culinary capabilities. Not surprisingly, I was told by a mushroom enthusiast in France about how dodgy salesmen knowingly mix up their batches with different varieties.

This all being said, the last thing I want to do is discourage you from harvesting this species. It’s well worth the effort to at least try your local varieties; they could be delicious. Even the ones that don’t live up to the prestigious Spanish “Niscalo”, can be cooked up in many splendid ways if you know what you’re doing in the kitchen.

Natural History Of The Saffron Milk Caps

Like many other highly regarded mushrooms, Saffron Milk Caps are impossible to cultivate artificially. They only grow in the wild, forming “mycorrhizal relationships” with the roots of specific trees with whom they form symbiosis. Basically, the mushrooms acquire nutrients and minerals from the soil and exchange them with the tree for energy-rich sugars. It is from their plant hosts that Milkcaps obtain all of their biological carbon.

This relationship makes Saffron Milk Caps an essential part of forest ecosystems across the world. While they are best known for occurring with various pine species, they can occur with other conifers and even hardwoods.

Diversity and Taxonomy of Saffron Milk Caps

Saffron Milkcaps are in the genus Lactarius, along with hundreds of other species. These are all pretty easy to recognize because when their tissues are damaged, they exude latex. This latex is often milky-white, hence the name milkcaps. The name Lactarius refers to Latin words for milk, like lactose and lactation.

So, to determine if a mushroom happens to be a type of Lactarius, you can simply cut the mushroom or break some of the gills. If the mushroom is relatively fresh, it’ll ooze out a liquid that is either white, clear, yellow, orange, or red. Certain species now also belong to the closely related genus Lactifluus.

As I mentioned in the introduction, there are a wide variety of Saffron Milk Caps. While these are often all referred to as Lactarius deliciosus, the truth is that this exact species doesn’t occur in North America. This name has been misapplied to North American species, but emerging research suggests that this species only really occurs in Europe (Nuytinck, 2020).

So, when I (and most non-European foragers) talk about Saffron Milk Caps, we are using a loose term that includes many different species and varieties. These all belong to a larger group, which is simply referred to as Lactarius in the section Deliciosi. Some of these are great edibles, others are mediocre, and some are not even named by science!

Identification Of Saffron Milk Caps

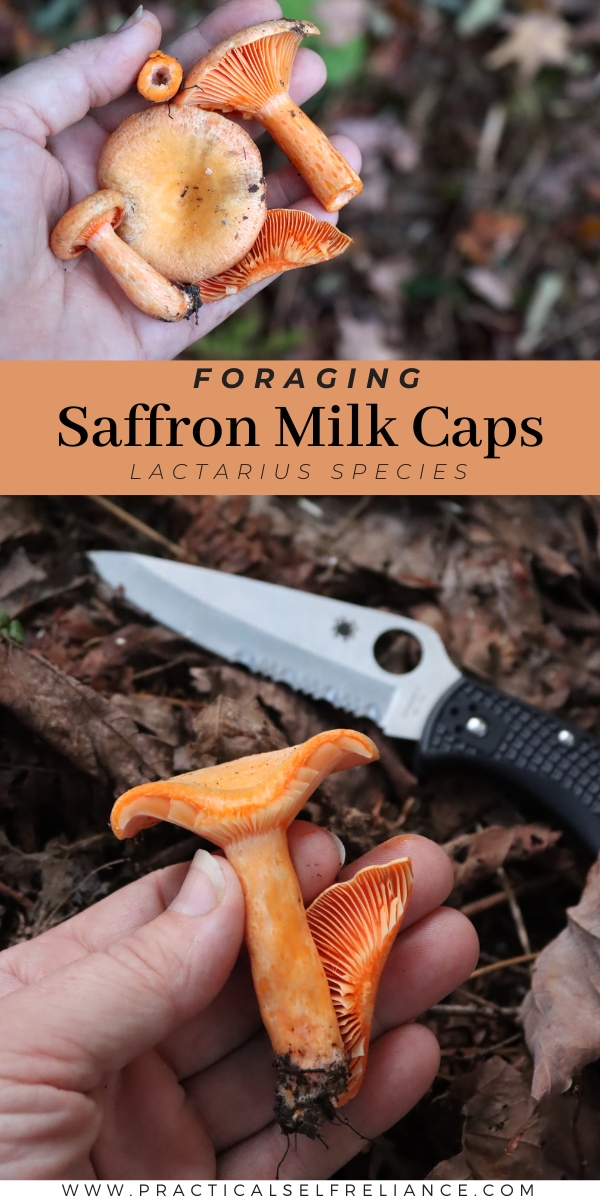

Saffron Milk Caps are medium-sized mushrooms with caps about 5–10 cm in size, although there are outliers. They are cream-orange to carrot-orange in color but often have stains or tinges of green coloration. These stains happen when the mushroom is old or damaged and their flesh begins to oxidize, so you won’t see it on pristine specimens. If you see this green color, that’s a great sign that you’ve probably got an edible Milk Cap!

The cap tends to have a central depression and an enrolled margin, particularly when young. As the mushroom ages, the cap becomes more funnel-shaped. That cap also bears concentric rings of darker coloration on its top surface, particularly towards the margin. The gills are closely spaced together, light in color, and relatively brittle. In the classic European species, you find darker-colored circular “dimples” on the stem, which have a bubble-like appearance.

The latex exuded by Milk Caps is orange to red and slowly oxidizes to green. When cut down the center, the flesh is white. The taste of the raw mushroom is pleasant but slightly bitter, while the smell is sweet and agreeable.

Generally speaking, if you follow the features listed below, you’ll be sure to have one of the edible milk caps. I’ve put some of the most important things to look out for in bold.

Summary of Identification Features

- Cream-orange to carrot-orange color, with a tendency to stain green.

- Cap has a central depression and enrolled margin when young, becoming more funnel-shaped as it ages.

- The cap has concentric rings of darker color, especially near the margin.

- Gills are closely spaced, light in color, and relatively brittle.

- The latex exuded is orange to red and oxidizes to green.

- Raw mushrooms taste generally pleasant (not spicy or extremely bitter)

- The smell is sweet and agreeable.

While this should be pretty obvious, NEVER eat a mushroom unless you are 100% sure of its identity! If you have any doubts, confirm them with an expert. If doubts remain, throw it out!

Varieties of Saffron Milk Cap

I’ll be honest and tell you that learning all the different types of Saffron Milk Caps can be difficult. This is a pretty long list below, and it’s not even complete. You don’t need to know the exact species just to know that it’s an edible variety, although it’s still valuable to try to ID it.

Europe

Consider that these are the originally described species, known only to be native to Europe. There are “twins” of these species in other parts of the world, and in some regions, they may be introduced.

The “True” Saffron Milk Cap (Lactarius delicious)

This species only occurs in Europe and follows all of the characteristic features described above. There are closely related species in North America that still use this name. Known to almost only occur with Pine.

False Saffron Milk Cap (Lactarius deterrimus)

Edible, but not as highly regarded. A European species that can be distinguished by a latex that turns dark-red to maroon after 5-15 minutes.

Cap is often darker in color as well, and the gills are partially interconnected.

Salmon Milk Cap (Lactarius salmonicolor)

Very similar to Lactarius deliciosus but with a pale salmon color. The most distinguishing feature is that it doesn’t, or only very lightly, stains green.

It is technically a European species, but it also has some North American twins. In Europe, it also occurs with Fir and Spruce but not with Pine.

Bloody Milkcap (Lactarius sanguifluus)

This species is distinguished by its pale color and dark red staining before turning green.

North America

These are the varieties of saffron milk cap that occur in North America:

Western Montane Saffron Milk Cap (Lactarius deliciosus var. areolatus)

This is a unique species without a formal scientific description or species name. Even still, this is the common version of the Saffron Milk Cap in the mountains of the western United States.

Known from Engelmann Spruce, Lodgepole Pine, and likely other conifers from mountainous regions.

Red-Bleeding Milk Cap (Lactarius rubrilacteus)

This species has a dark-red latex and mainly occurs with Douglas Fir.

It can be found throughout the West, including Colorado and the Sky Islands. Considered a good edible.

Northeastern Saffron Milk Cap (Lactarius deliciosus var. deterrimus)

Like others, this is a distinct species but is currently listed as a variety. It is known from the northeastern United States and surrounding regions.

It grows with northern white cedar, eastern white pine, and other conifers, and is known to grow in very wet and boggy forests.

Non-Staining Saffron Milk Cap (Lactarius thyinos)

Also called orange milkcap because it tends to exude a bright orange latex, this species is also found in boggy areas in the Northeastern United States.

The biggest difference with this species is that it does not stain green AT ALL!

It grows side by side with the northeastern Milk Cap (mentioned above) but is differentiated by the lack of staining, among other subtle features.

Spruce Milk Cap (Lactarius deliciosus var. olivaceosordidus)

This species is known from Sitka Spruce forests in the coastal regions of the western United States and Canada. You can also find a similar species known as Lactarius aurantiosordidus in the same region.

The Blue Milk Cap (Lactarius indigo)

This species is quite different because of its brilliant blue color! Even the latex is blue. It’s a beautiful species and closely related to the Saffron Milkcaps.

Despite its shocking color, it is also considered an edible choice. Typically grows with Oaks.

Saffron Milk Cap Lookalikes

When we talk about lookalikes, the species you’re going to want to watch out for are different species in the Lactarius genus. There are a lot of these, so I’m not going to bother naming them all. None are considered severely toxic, and they are pretty distinct from the Saffron Milk Caps.

Saffron Milk Cap Lookalikes will have some of these characteristics:

- They have white, clear, or bright yellow latex. These may change color as they oxidize, which can be important to determine specific species.

- They do not exude latex.

- They have a rough or pubescent cap surface.

- They have an unpleasant smell or a spicy flavor.

- They have no evidence of concentric rings on the cap surface.

- They do not stain green, even faintly.

The saffron milk cap look a-like shown above does not have concentric rings on the surface and does not stain green (or stain at all).

Though the mushroom above does have concentric rings, it also has a bristly fuzzy cap.

Where to Forage Saffron Milk Caps

You can find different types of Saffron Milk Caps in almost any coniferous forest. Pines, Spruce, Fir, Douglas Fir, Hemlock, and even Cedars are all known hosts. Milk Caps also readily occur in pine plantations and areas where pines have been introduced; this includes Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand.

Western North America

The coniferous forests of the United States are excellent hunting grounds for Saffron Milk Caps. Most of the species here are considered average edibles, although some enthusiasts do enjoy eating them. When it comes to hunting grounds, there are two distinct zones we can talk about.

The first are the coastal zones with Sitka Spruce that occur from northern California up into Alaska. Here you can probably find at least three different species, two of which are associated with Sitka Spruce and another with Douglas Fir. You can also find them along with Monterey Pine. There are likely at least 4–5 varieties or species.

The second zone is the mountainous regions like the Sierra Nevadas, the Cascades, the Sky Islands, and the Rocky Mountains. Here you can find them with lodgepole pine, true fir, Douglas fir, and Engelmann spruce.

Eastern United States

The eastern United States has several “myco-regions” that produce Milk Caps. These are the coniferous forests found in the Gulf States, the Appalachian Mountains, the Northeast, and the Great Lakes. You can also find the Blue Milk Cap with Oaks in many different parts of the country.

Around the Gulf and in Appalachia, you mostly find Saffron Milk Caps with different types of Pine. You can also find them with other conifers in extremely wet and boggy forests. This is the case in the Northeastern United States, where they can be abundantly harvested in conifer bogs, particularly with cedar. Some species have been claimed to also occur in hardwoods.

Europe

In Europe, most Saffron Milk Caps are associated with different types of Pine. The most prized are the ones that occur in the Mediterranean regions. They also occur with Spruce and other conifers in more continental and boreal Europe.

Southern Hemisphere

In the Southern Hemisphere, Saffron Milk Caps are very common in introduced pine plantations. They seem to be one of the most voracious mushrooms in these conditions, and some trees are even sold pre-inoculated with them!

When To Forage Saffron Milk Caps

The season for Saffron milk caps usually corresponds to cool or cooling weather. In hot arid climates like California, they’re a winter mushroom, but in cool climates like the Northeast they can be found as early as July. In the southern hemisphere, the timing is just the opposite, and corresponds with their winter months.

- California (Oct – Feb) – The California season starts in the fall and continues into the winter. The mountain season is mainly in the fall, while on the coast, you can find specimens of Sitka spruce in the spring!

- Pacific Northwest (Sep – Dec) – In Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska, you find a pretty classic fall season. This season can be extended into the winter within mild coastal zones.

- Southeastern United States and Appalachia (June – Dec) – All along the Gulf States to Georgia and Florida, you get a summer and fall season. The Appalachian Mountains have a similar season, although it tapers off earlier with cooling temperatures.

- Northeastern United States and Canada (July – November) – Here, the season starts with the summer rains and ends with cooling temperatures in the fall. This is pretty much the same season seen in the midwestern states.

- Southern Hemisphere (March – July) – In Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and other parts of the southern hemisphere, the season occurs from March to July.

- Europe (July to Dec) – Europe is a whole continent, and the exact season can vary depending on your location. Generally speaking, it gets triggered by heavy rain events during mid to late mushroom season. The season ends earlier (about November) in northern countries and can last until late winter in the southern parts of Europe.

How To Forage Saffron Milk Caps

Most of you probably know this already, but always forage with the utmost respect and consideration. Leave no trace and respect the local communities that utilize these forests. If necessary, ask permission before foraging on said land. Be careful where you’re walking and try not to cause too much erosion, especially if you’re in a large group.

I always tell people that mushroom hunting isn’t exactly a sport. Take your time, go slow, keep your eyes peeled, and don’t be afraid to get sidetracked by all the beautiful biodiversity that exists in these forests.

If you’re in the right habitat at the right time of year, you should have pretty good chances to run into some Saffron Milk Caps. They’re not exactly rare mushrooms and are rather easy to see thanks to their color and size. If you don’t find any Milk Caps, there are other edible mushrooms such as Chanterelles, Black Trumpets, Yellow Feet, and maybe even Boletes that you can find at the same time of year.

Once you do finally find a patch of what you believe to be Milk Caps, you should take a closer look to confirm their identity. Is it orange with concentric lines on the cap? If I cut the gills does a bright-orange latex exude? Does it smell sweet and meet the other characteristics mentioned?

If you do indeed have Milk Caps, it doesn’t hurt to take a minute and scope out the patch from where you’re standing. If you’re lucky, there will be plenty to harvest, and you can pick the best-quality ones from the bunch. If you’ve never eaten this variety, I recommend only taking a single meals worth your first time. There’s no point in harvesting a lot if you don’t end up enjoying it. Always try to leave about half of the patch, even if it’s just older and younger specimens.

When it comes to the actual act of harvesting, you can either pluck and then cut, it or just cut it to begin with. As I’ve discussed in past articles, there are two opposing opinions of what is best, and they both have valid points. Scientifically, neither is the most “sustainable” way to harvest them. I typically recommend what’s most approved of by your local community.

This being said, cut off the dirty part of the stem before putting it in your bag or basket. This will help keep all your other mushrooms clean. Remember that these mushrooms are somewhat fragile, so take great care not to damage them during transport.

Once you get home from the mushroom hunt, it’s typically best to take care of your mushrooms immediately. I know, sometimes you just want to relax and drink some tea after a long walk in the woods, but this will ensure your mushrooms stay in good shape.

- If they are really dirty, I’ll just hose them down (or you can do it in a sink) to remove every bit of dirt. Afterward, lay them all out on flat pieces of cardboard in a warm place with good ventilation and let them dry for 12–24 hours. Just enough so they’re not saturated.

- If they’re not super dirty, you can just brush off any dirt or leaves and then keep them in a decently well-ventilated area. You can throw them in the fridge too; just try not to stack them on top of each other too much.

Cooking and Using Saffron Milk Caps

There are countless ways to prepare Saffron Milk Caps. They can be sauteed with garlic and veggies, added to stir-fries, or made into a tasty omelet. They also make an excellent addition sliced, fried, and added to soups! Like most mushrooms, make sure to cook these well and do not eat them raw. If it’s your first time eating them, don’t consume them in large portions.

Personally, my favorite way to cook these is to keep them whole, not chopped up. Honestly, I do this with a lot of mushrooms nowadays, but these are particularly good for this strategy.

- Remove the stems and cut the extra-large specimens in half.

- Throw both the caps and stems into a hot pan with oil. Throw in garlic, salt, pepper, chili flakes, and more garlic. You can also add finely chopped onion or cherry tomatoes.

- Put a lid on top of the pan and let the juices come out of the mushrooms. Let it cook in its own juice with the lid on for a good 5-10 minutes; afterward, take the lid off and let it evaporate.

- Once the water is evaporated, add a bit of butter and let it fry! Cook it until golden on both sides. If you want, you can add some shredded cheese or mozzarella on top and let it melt. Add some parsley, basil, or other aromatic herbs once the temperature has dropped.

- You can serve it Mediterranean style with some nice tomatoes, olive oil, bread, pasta, olives, or whatever else calls you!

Preserving Saffron Milk Caps

Dehydrated: This is not recommended for Saffron Milk Caps. I’ve never tried it, but the fact that nobody does suggests something. Perhaps dried and powdered, it could make a decent condiment.

Frozen: You can cook your mushrooms and then freeze them. This will preserve the flavor and texture, compared to freezing them uncooked.

Pickled: This mushroom is commonly pickled in many parts of Europe, both as a “quick pickle” with vinegar and also lacto-fermented. You can find recipes for how to do this online. My favorite pickle recipes often have mustard seeds, pepper, chili, garlic, and other spicy or aromatic ingredients. You can also add some onion and carrot, which can add a sweet element.

Jerky: I’ve never had it in jerky, but I could imagine it being suitable for this. You can find recipes online, but they generally entail cooking the mushrooms in a marinade and then dehydrating them.

Great article! I’m trying to identify a mushroom that I believe is of the Lactarius genus. It has orange gills. The center is somewhat hollow. It Stains green. The latex however turns maroon and the cap is a tannish color with older ones being inverted, with no concentric rings that I can see. It was found in a ring of mushrooms next to a spruce tree in our yard. I have a picture but not sure how to post it! LOL

Unfortunately there isn’t a way for you to post a picture here. If you’re on Facebook, I believe there’s a good mushroom identification group there that can probably help.