Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

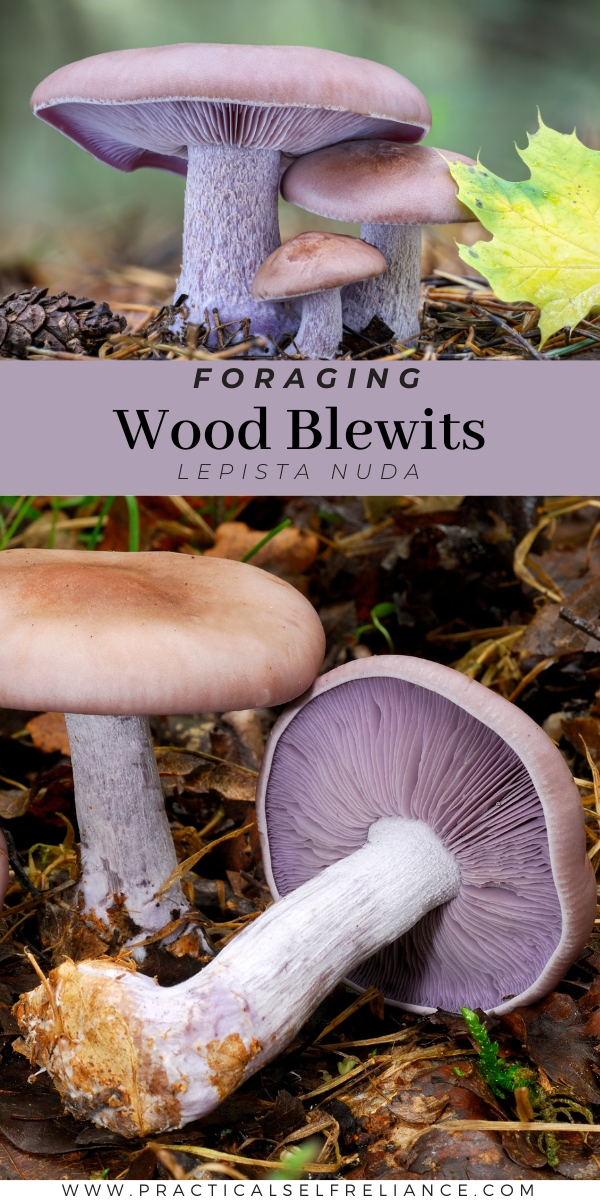

Wood blewits (Lepista nuda, or sometimes called Clitocybe nuda) are a species of edible wild mushroom with a fruity aroma and vibrant purple color. They’re fun to find in the woods, and delicious to eat, provided you can identify them correctly.

This article was written by Timo Mendez, a freelance writer and amateur mycologist who has foraged wild mushrooms all over the world.

With its fragrant fruity aroma, vibrant purple tone, and wide-spread presence, The Blewit is an edible mushroom that should not be overlooked. While it’s often underappreciated compared to other esteemed species, like Chanterelles and Boletes, who receive “the royal treatment” in the world of foraging, I’m here to tell you it’s worth making room in your basket for Blewits.

Indeed, the vibrant amethyst color scares away novice foragers, but those who know harvest it by the basket load for its pungent and delicious flavor. Despite its unconventional appearance, there is no need to fear properly identifying it. With a bit of precaution and care, it is rather straightforward to distinguish it from any toxic lookalikes.

Ecologically, Blewits are opportunistic and exceptionally adaptable decomposers. They feed on a wide variety of organic substrates, including leaf litter from hardwoods and conifers. They are also commonly found in gardens, landscaping, and parks growing on decomposing wood mulch.

While it’s not an exact science, some folks even successfully cultivate them at home in their gardens. Blewits are typically found late in the season and are triggered to fruit by cooling temperatures in the fall.

The scientific name of the Wood Blewit is a bit controversial, and the taxonomy isn’t quite settled. While the name Lepista nuda is regarded as the contemporary name, many well-respected mycologists stick to the name Clitocybe nuda (1, 2). While this isn’t that important, it is something to keep in mind when using field guides or doing online research on this mushroom. The origins of the name “Blewit” are not entirely clear, although it likely evolved from the name “Blue Cap” or “Blue Foot”.

It should also be noted that there is a closely related “Field Blewit” which is very similar in culinary value and appearance. The main difference is the habitat in which you find it (fields instead of woods) and that the cap has a rather dull color, and the only bright violet part is the stem.

How to Identify the Wood Blewit

Proper identification is rather easy, although there are a handful of toxic mushrooms with superficial resemblance.

The main point is to not utilize purple coloring as the sole identification feature, as this will lead you down the wrong path. It should also be noted that there is a large number of regional variations found across the world, and it is a “species complex.”

To begin with, the Blewit is a typical stem and cap mushroom. You find them in the woods growing directly from leaf litter, oftentimes on the sides of trails. It is often wider than it is tall, with a cap usually ranging from 2 to 5 inches in width and a total height of just 2 to 3 inches. This can vary depending on the specimens.

The cap is slightly concave when young, then flattens out, and eventually becomes convex and funnel-shaped. The cap margin is heavily enrolled until it is completely mature, and then it may have an uplifted and even wavy margin.

While the name suggests a “blue” color, it is more of a violet or amethyst color that fades to a dull-brown color as it matures. Don’t be surprised if you find them and they’re not even slightly purple, as the color changing is an important feature. Heavy rains and excessive saturation will also result in a dull color.

The gills are attached to the stem and are very close together. The entire mushroom is rather firm and not brittle to the touch, including the gills. The stem is often stout, sometimes with a a pattern featuring light-colored stripes. The base of the stem is sometimes bulbous, and more often than not attached to the duff with thick, fluffy mycelium that protrudes from the base.

The mushroom has an attractive fruity aroma, which mycologist David Arora described as “frozen orange juice”. While that’s not a descriptive scent you would expect from a mushroom or anything at all, it does fit the aroma.

I’ll be honest, I’ve never smelled frozen orange juice, but it feels right. Like the flat aroma of store-bought pasteurized orange juice. Others describe it as floral, fruity, or perfumed.

The spores of the Blewit are pinkish and light in color. This is important for easily distinguishing it from some of the purple Cortinarius, which have a rather present and rusty-brown spore print that is often deposited below the mushroom and its stem.

Blewits have no tissues that cover the gills when young.

Blewit Lookalikes

Keep an eye out for these blewit look alikes:

Cortinarius

There are many different purple mushrooms in the genus Cortinarius that could be mistaken for a blewit. Cortinarius has rust-brown spore prints that are either deposited below the mushroom or on the stem. In contrast, Blewits have a light pinkish spore print.

Cortinarius also has a fluffy cotton-web tissue that covers the gills in the young mushrooms. Reminence of this cottony web is usually present on the stem.

Certain cortinarius may also have textured caps, and they usually don’t become a dull brown with age.

Amethyst Deceiver (Laccaria amethystina)

These are generally much smaller than blewits, and almost always taller than they are wide. Their stems are thin and lanky and their caps are rather small.

They’re usually attached to dirt as opposed to leaf litter, and the gills are much further split apart.

The gills of Laccaria species are generally rather thick and fleshy.

Other Lepista species

Lepista sordida is very similar to the Wood Blewit but generally much duller in color and slightly white.

Lepista personata is the field Blewit and generally has a dull white cap and violet stem. These grow in fields as opposed to forests.

Where to Find Blewits

Blewits are rather ubiquitous mushrooms, occurring in temperate forests across the world. They are common in deciduous forests but also coniferous forests and alongside certain hardwoods as well. While not technically their native habitat, they have also adapted to gardens, parks, and landscaping, with a particularly strong affinity for wood mulch.

They often occur in areas that accumulate large quantities of leaf litter, such as the sides of trails or at the bottom of forested slopes. They thrive in humus-rich soils and extend their mycelium directly onto the fresh, decomposing litter.

Since this mushroom is so ubiquitous, I don’t find it entirely necessary to discuss in detail all the places you can find it. They can be found in coastal, inland, and mountainous forests, and their range extends into subtropical and montane-tropical regions as well.

When to Find Blewits

Blewits typically begin fruiting as temperatures decline and thus continue as long as there is adequate moisture and no frosts. Freezing temperatures usually mark an end to the proper season for Blewits.

California (October to February)

The mild temperatures in California allow you to find Blewits starting in late fall and throughout the winter. The season tends to be longer in coastal regions and much shorter in inland and mountainous regions.

Pacific Northwest (September to January)

Here, the season usually starts around September with cooling temperatures. It typically starts earlier in the north and makes its way south. They can be found until midwinter, or even later, in coastal areas.

Midwestern United States (August to November)

Here, the Blewit season starts at the end of summer and continues until the first frosts at the end of fall. It typically peaks in October.

Eastern United States (September to December)

The Blewit season here can start as early as the end of summer but more often starts in the fall. It begins in the north and steadily makes its way south as temperatures cool. The season peaks around October and usually ends by the beginning of December. Occasionally, you find specimens in December.

Florida (October to February)

Blewit season starts a bit later in the subtropical climate of Florida. It usually begins around October and can continue all winter long into February, typically peaking around December.

Colorado and Southwestern Sky Islands (July to September)

In these mountainous regions, the Blewit has a short summer season triggered by monsoons. It doesn’t appear to be very common in Colorado, and there are numerous reports in the Sky Islands of Arizona. In the southwest, it seems as though there could also be a short spring season in March.

How to Harvest Blewits

When harvesting anything from the wild, always do so with the utmost care and respect. Don’t litter, cause erosion, or harvest without permission if you’re on private property. Respect the mushrooms and the fungal mycelium they grow from, as well as all the other organisms and people that form part of the ecosystem.

While many people prefer to cut mushrooms with a knife, there is no conclusive evidence that this is beneficial for the fungus. In France and other parts of the world, picking is said to help prevent infections that can occur when a part of the stem is left attached to the mycelium. The little research conducted on the subject showed that picking does not impair the future production of the mushrooms, although more studies are necessary.

I find that cutting is generally beneficial just because it’s a lot cleaner than picking. This is especially true for blewits, who often pull up a bunch of leaf litter along with their stem. It’s important to always pick clean, as this will significantly reduce the quantity of cleaning you’ll have to do back at home.

Generally speaking, you should only harvest mushrooms that are fully developed but not too old. Leave those that are too small and those that have a fully convex cap and have turned a dull brown. Fully mature mushrooms are nowhere near as delicious as the prime ones. Out of respect, it is only best to leave some behind for the animals, and maybe even future pickers.

Regarding transportation, it’s best to do so in a wide basket to avoid piling them up on top of each other, as can happen in a bag. Baskets or mesh bags also help disperse spores as you move through the forest.

Once you get home, place them in a cool and dry place immediately. Don’t let them sit around in a bag as they’ll go off quickly like this. Instead, lay them out on a counter or table so they are not all on top of each other. You should not wait longer than 2-3 days before cooking, as blewits do not have the best shelf life. If they’re already on their way out, you should cook them immediately for your next meal!

Cooking Blewits

Blewits have a rich flavor that entices chefs from around the world. It’s fruity, aromatic, earthy, and really a unique sensory experience. It must be said, the flavor of this mushroom can greatly vary depending on where it is harvested. Different varieties in different locales may have distinct flavors and the type of substrate they are growing on is also said to affect the flavor. Some say those under Eucalyptus and Cyprus are not equally delicious.

Always make sure to thoroughly cook Blewits! If consumed raw, they may cause unpleasant difficulties in digestion!

There are many different ways to prepare them, but generally speaking, I like to fry them with the classic old butter, garlic, and onion technique. Simply add them to a pan with these ingredients and fry them until golden. Then use this as a topping for pasta, soups, salads, or anything else you can imagine. If they are extremely wet, you may choose to add them to the hot pan by themselves first and only add the butter once all the moisture has evaporated. In some European recipes, the mushrooms are briefly boiled for 4-5 minutes before frying.

Blewits go great in many different dishes. I prefer to keep them whole or in rather large pieces to conserve their texture and flavor. If you mince them into small pieces, they easily get lost alongside other ingredients in the dish. Consider using Blewits in omelets, pizza, soups, and salads, or to make a rich, creamy sauce. Add a little bit of white wine to the sauce to make it stand out! You can almost always garnish blewits and any dish that contains them with a bit of chopped parsley.

Preserving Blewits

When you find a big patch of blewits, sometimes you need a few good ways to preserve them.

Drying

Blewits dry well and can be saved for years under proper storage conditions. Just make sure they are nice and crispy before placing them in a tightly closed jar or vacuuming them.

Pickling

You can also briefly boil the mushrooms for 5-10 minutes in a bit of water. Let it cool down, and then use the mushrooms and remaining liquid as part of your favorite pickle recipe!

Freezing

Alternatively, you can also cook the mushrooms, either plain or seasoned, and then freeze them. This way, you can easily incorporate them whenever you need them. Don’t freeze them fresh, as this will ruin the texture!

Mushroom Foraging Guides

Blewits aren’t the only mushroom in the woods!

- Morel Mushrooms

- Chaga Mushrooms

- Birch Polypore

- Tinder Polypore

- Witches Butter Mushrooms

- Puffball Mushrooms

- Shaggy Mane Mushrooms

- Reishi Mushrooms

- Turkey Tail Mushrooms

- Dryad’s Saddle