Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

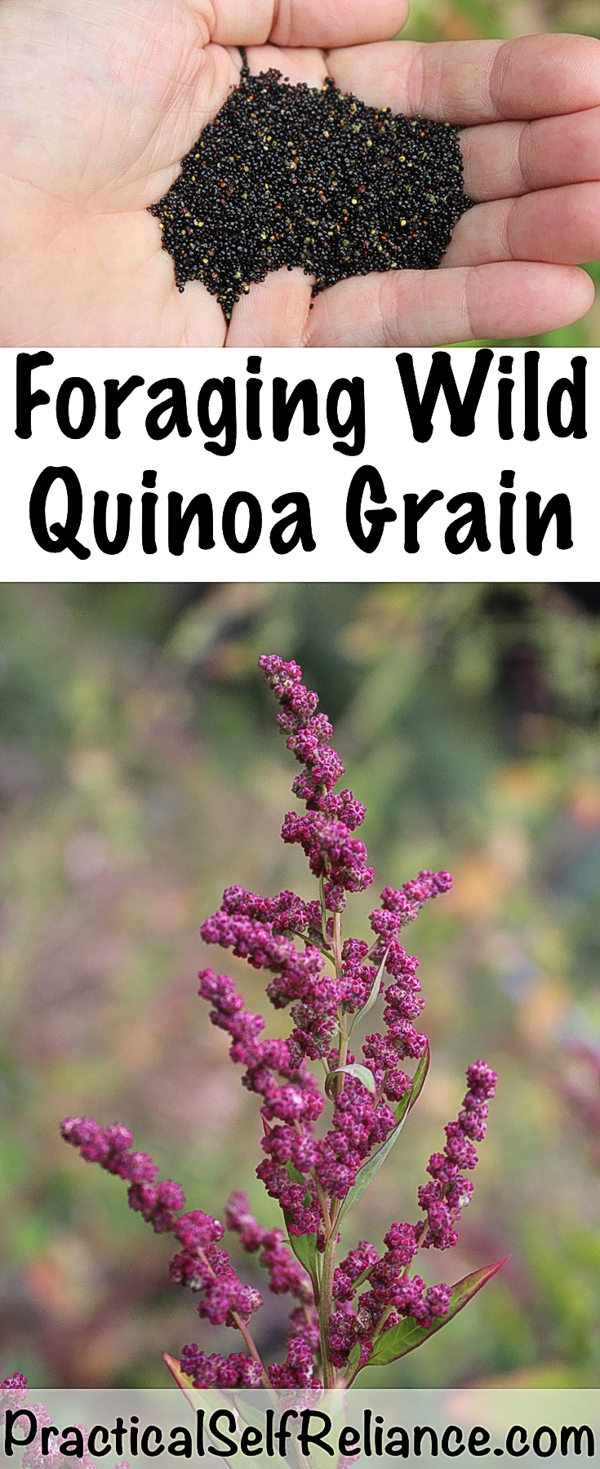

Every grain we have today has a wild ancestor, but some are more domesticated than others. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) is relatively new to domestication, and its wild cousin (Chenopodium album) is not that different than the modern cultivated grain. The seeds may be a bit smaller, but the plants look almost identical when they sprout in the spring.

What you may not know, however, is that wild quinoa likely grows in your backyard. Also known as goosefoot, it’s almost as common as dandelions, and it’s viewed as a weed by gardeners around the world. Most foragers harvest its leaves as a tasty salad green in the spring, but if you allow the plants to mature, they’ll produce a wild grain crop in the fall.

Most commonly called goosefoot because of its goose foot shaped leaves, Chenopodium album also goes by the name pigweed and fat hen because of its use as a nutritious animal feed.

The grain was eaten by peoples all over the world, even alongside more modern domestic grains. Remnants of goosefoot seeds have been found at Iron age, Viking age, Roman sites and more recent British archeological sites. Goosefoot seeds were mixed with other wild grains in the stomach of Dätgen Man, a body found preserved in a Danish bog from 300 BC, as well as several other preserved bog bodies throughout history.

In India, goosefoot (Chenopodium album) is still cultivated for its leaves and seeds. The leaves are used in curries like spinach, and they go by the name bathuwa. The seeds are eaten as a cooked grain.

“Just as Incan people in the Andes grew Chenopodium quinoa for its nutritious seeds, so Chenopodium album has long been cultivated in India. Napoleon Bonaparte, who always paid close attention to the diet of his troops, employed ground pigweed seeds as a flour supplement for his army’s endless bread. (Source)”

Goosefoot starts out pretty humble in the spring. The leaves taste a lot like spinach, but with a more deeply “green” flavor and far more minerals. The leaves are best on the smallest of plants, and once the heat of midsummer hits, they begin to bitter.

During summer’s heat, goosefoot plants “bolt” or go to seed just like any salad green. They’ll grow taller and produce tiny white seedheads at the top of leggy plants. By the fall, they’re nearly 5 feet tall bushy plants that barely resemble the small salad green of the spring.

As temperatures drop in the fall, the seedheads will mature. Once they take on a bright magenta hue, the goosefoot grain inside is ready for harvest.

The harvest itself is relatively simple. Just grab around each seed cluster in the palm of your hand, and gently strip the seed from the stalk.

Open your hand and you’ll find a crumbly mixture of goosefoot grain and chaff.

The tiny black dots are the goosefoot grain, and the green and red chaff need to be separated out of the finished grain.

The problem is, separating the grain from the chaff is surprisingly difficult. While with other wild grains like dock seed, the grain can be ground into a flour chaff and all, that’s not a great solution for goosefoot grain.

The seeds themselves are a very small proportion of the harvest, and it’s surprisingly bitter. My daughter is fond of eating the unripe goosefoot seed heads because while they’re green they taste like cauliflower, one of her favorite vegetables.

Once the seed heads change color in the fall, I find them unpalatably bitter. Beyond the rough taste, the chaff is the majority of the bulk.

My favorite foraging author, Samuel Thayer, sums it up nicely in his book A Foragers Harvest, “Some people that I have talked to do not separate the chaff from the seeds, but these are people who don’t eat much goosefoot grain, either. The chaff is mostly undigestible and it comprises most of the bulk of the seed material; I think you could eat all the unseparated goosefoot grain you want and still starve.”

He suggests separating the goosefoot grain by rubbing the grain between your hands and then winnowing away the chaff. It’s tricky because the chaff is only slightly lighter than the grain. I harvested the seedheads on a foggy autumn morning, and they were too damp for this to be practical.

As I rubbed though, I discovered something else interesting about goosefoot chaff…it contains a substantial concentration of saponins. The damp grains started to lather in my hands as I rubbed.

That’s also true of quinoa, and I have friends who cannot eat quinoa because it tastes like soap to them. Some people are more sensitive to it than others, and if you don’t taste it in domestic quinoa you likely won’t taste it in goosefoot grain either.

It was a fun find though, and my daughter commandeered all the extra goosefoot chaff at the end of this process and took it right to the bath. I have to say, watching a 3-year-old excitedly scrub herself with goosefoot chaff was one of the most entertaining parts of this whole harvest.

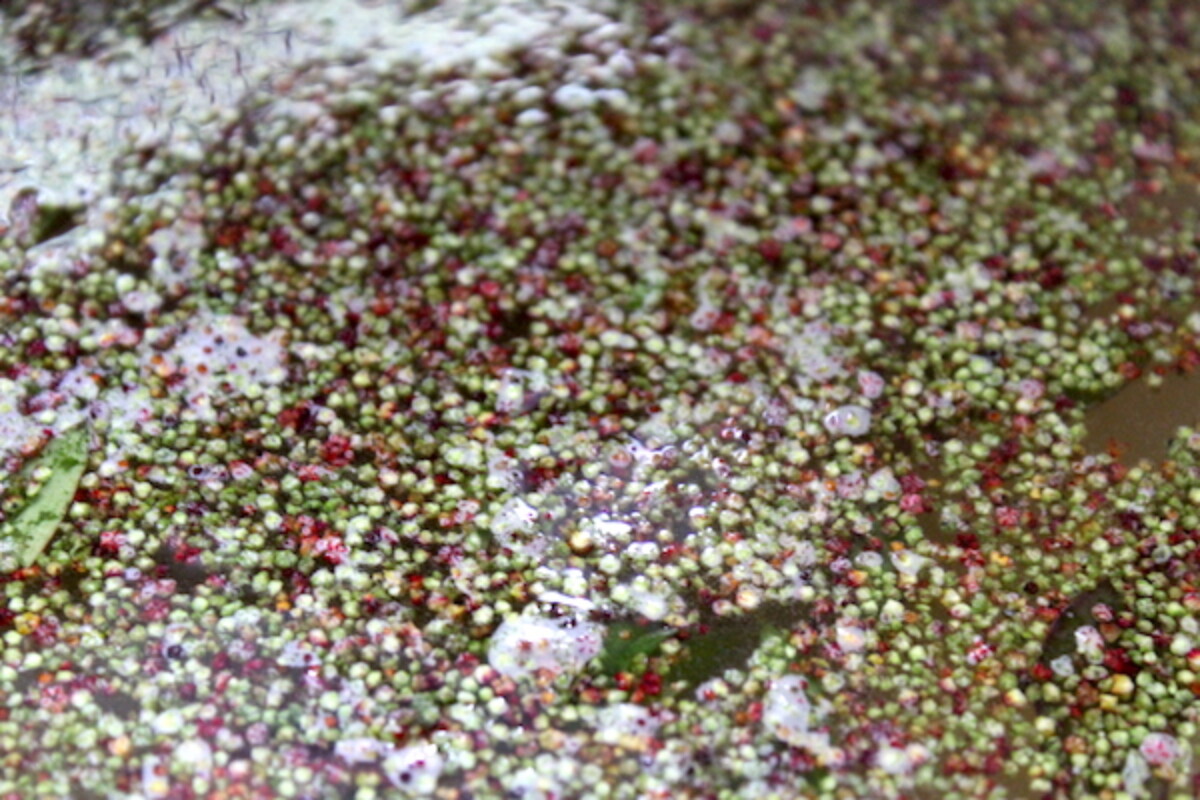

Since the grain was wet, I decided to try a wet extraction, in the hopes that the chaff would float and the grain would sink. I gave the grain a good rub between my hands and put it into the water. The vast majority of the chaff came right to the top.

I scooped the bulk of the chaff off the top of the water with my hand, and then carefully poured the water out of the bowl. The heavier chaff is still a bit lighter than the grain, and though it doesn’t float, it’ll pour out before the grain if you’re careful.

Slowly pour the water out of a bowl and then scoop the remaining chaff out, leaving behind just the small black seeds.

The yield was surprisingly small, and I harvested one tablespoon of wet goosefoot seeds from every 2 cups of harvested grain and chaff. Now it’s easy to see why you’d starve trying to eat it without winnowing it.

Even though the yield is small, I was able to harvest nearly 4 cups of chaff from one large goosefoot plant in about 2 minutes. Winnowing it took no more than 3 minutes start to finish using water. Assuming you have enough water on hand, and good containers for winnowing, that’s 1 1/2 cups of finished grain for every hour of labor.

It’s hard to say if it’s as nutrient-dense as quinoa. I simmered the seeds in water for about half an hour, and the seeds popped open in the same way as quinoa. Rather than being soft though, they much smaller and crunchier.

My husband said, “It’s like eating sand!” I wouldn’t go that far, but they were crispy. I think they have substantially more seed coat than domestic quinoa.

Given how abundant goosefoot plants are, it’s good to know about goosefoot grain for a survival situation.

Assuming you have enough water to process the grain from the chaff, with a little work you could sustain yourself until better harvests arrive.

You can easily remove the bitter soapy taste from quinoa by washing it until the water runs clear, then soaking it for 6-8 hours, discarding the water and wash it from the soaking water again. Maybe it can save you the trouble of the carful sorting.

It’s so good to see you teaching your young child to be self reliant. My step sons are sixteen and twenty, and they never leave their rooms on the weekends. Between Snapchat and video games, I can see their lives wasting away with little knowledge of anything nature-related. Even if everything works out optimally in the future, they will still be adults who face ever-soaring food costs and ever-dwindling natural resources. I’ve had talks with their parents, who see self-sufficiency more as a conspiracy theory for some future that will never exist. People are so comfortable nowadays that they can’t comprehend it ever being hard for them.

I’ve got to get them outside. I know that once they get out there they will be glad, but the current opposition is so strong. I have two 20×20 vegetable gardens, an herb garden and various others, and I have physical disabilities, so working the land alone is difficult. I think writing this all down has helped me see with better clarity that I am giving up too easily. It is up to me to give these boys a future and I need to fight for that. Thanks for being my sounding board. Your child is pretty lucky to have you.

Thank you so much for your kind words. I hope you are able to make a positive impact on their lives. Feel free to come back and give us an update.

I’ve been cooking my lambs-quarter, and wondering about the seeds. So you’ve answered that, and I’ll leave it out there for a while. My big question is about timing. I have a lot of timothy and miscellaneous grasses, that are very green. I want to mow, but I want to try harvesting them. I brought in a few bunches yesterday to see if they would dry out and I could eat them. Timothy and one mystery grass. And the dock is way done, brown and hard – can I gather and eat it now?

If the dock is done now then you can definitely harvest it and eat it.

Thanks. I have a bunch of doc seeds sitting in a jar waiting for me to figure them out. I also have a lot of timothy, still chaff mixed with grain, sitting in a bowl of water. I thought those round green things were seeds, but I see some tiny black seeds at the bottom of the bowl. This is discouraging. Maybe I should plant wheat.

I’m sorry that you’re discouraged. You will just have to decide what the best option is for you.

Thank you for the education on how to use the seeds from goosefoot, aka lambs quarters! I had no idea it was related to quinoa!

Pigweed is an entirely different plant, whose potential I’m also researching, because it is growing in my “garden” alongside copious quantities of goosefoot.

You’re very welcome. So glad you enjoyed the post.

Ashley, thank you again for sharing! I’ve been LOVING my lambs quarter since spring, and wonder whether THREE of my uses are safe:

1. Are there health-related down-sides to eating the leaves once they develop brown spots (whether rust or deterioration)?

2. Even before the chaff turned magenta, I’d been stripping it (with the seeds) and adding it to rice, eggs, soup, you name it. I LOVE the crunch of these teeny grains! I so far don’t mind (and even like) the chaff. Are there health-related down-sides to eating a lot of it?

3. Finally, when I learned that the leaves have a decent amount of kidney-stone building oxalates, I started boiling this and other leafy greens. I’ve never had a kidney stone. So is this necessary even for those like me who eat a ton of it? (This one’s on my list of questions for my naturopath, but I ask as I know you think about these things and might have insight.)

Thank you again!

Brendan

Good questions…and unfortunately I don’t have much in the way of good answers. As to eating brown spottly leaves, I imagine that’s no different than eating other produce with spots/discoloration and most people avoid it. Whether that’s good or bad is debatable, and I have no idea if there’s any issue with it.

Historically, I imagine the chaff was eaten a lot since it’s a heck of a lot simpler to just eat the whole seed head then to process it, but I have no idea if eating it in high quantities will cause issues. Just because people ate it in 10000BC doesn’t necessarily mean it’s fine. It’s totally possible that it has really high oxalic acid content, more than other parts…or it could be just any other plant tissue. There’s no testing of it that I know of.

As to the greens, it’s actually a really common green in other parts of the world, but it’s usually a cooking green. That said, in most of the world, spinach is a cooking green too, the US is more salad focused than many developing nations where cooked food is often more trusted. I was curious about the specific content, and I found this article which has a really helpful chart:

https://www.eatthatweed.com/oxalic-acid/

It shows that it’s about double the content of spinach, but lower than purslane and rhubarb. I eat A LOT of raw rhubarb, like probably an average of 3-4 stalks a day when it’s in season. It’d take a lot of work to eat that much lambs quarter, but everyone responds to things differently.

I’d guess you’re a lot healthier eating a boatload of lambs quarter than you are eating bagged supermarket salads that keep ending up contaminated with e.coli and such. Whether or not that’s a scientific fact, I have no idea, that’s really just my opinion.

Either way, I’m so happy you’re enjoying tasty wild greens, but so few people eat them now that there’s not much science on it and I can’t find much concrete info with which to answer your very good specific questions.

Thank you, Ashley: You might not have solid answers, but I very much appreciate your insight and reflections!

I’m trying to grow this in our backyard (helped a neighbour ‘weed it out’ of their lawn and transplanted it) but either the birds or squirrels or something else really likes it and has sliced the leaves up in straight lines… any idea which pest(s) are the likely culprit?

Will do my best to harvest lots of seeds this fall and just plant enough next year that the wildlife eats its fill with enough left over for us too…

Hmmmm, I really don’t know what could have caused that. Good luck!

Sounds like grasshoppers

I’m wondering if it could be used as dye? That’s a beautiful color.

Good question! I don’t have the answer to that, since I don’t know much about natural dye, but it didn’t stain anything we worked with.

Very useful information. I live in Bahrain and we have plenty of these plants.

Have you made flour from the seeds?

I haven’t made flour from the seeds yet, no, but if you try it, let me know how it goes!

I had no idea about this wild food. Now I want to find some and try extracting and cooking the seeds. To be honest, I LOVE my grains to be crunchy, which is one of the reasons i LOVE my quinoa a bit undercooked. Thank you for sharing this!