Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) is wild, edible native plant that’s commonly used as a seasoning. Add a little wild flavor to your spice cabinet with this beautiful native plant.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) has always been a favorite of foragers looking for unique flavors right out in the woods. It has a warm, spicy flavor that’s reminiscent of allspice, and every part is edible.

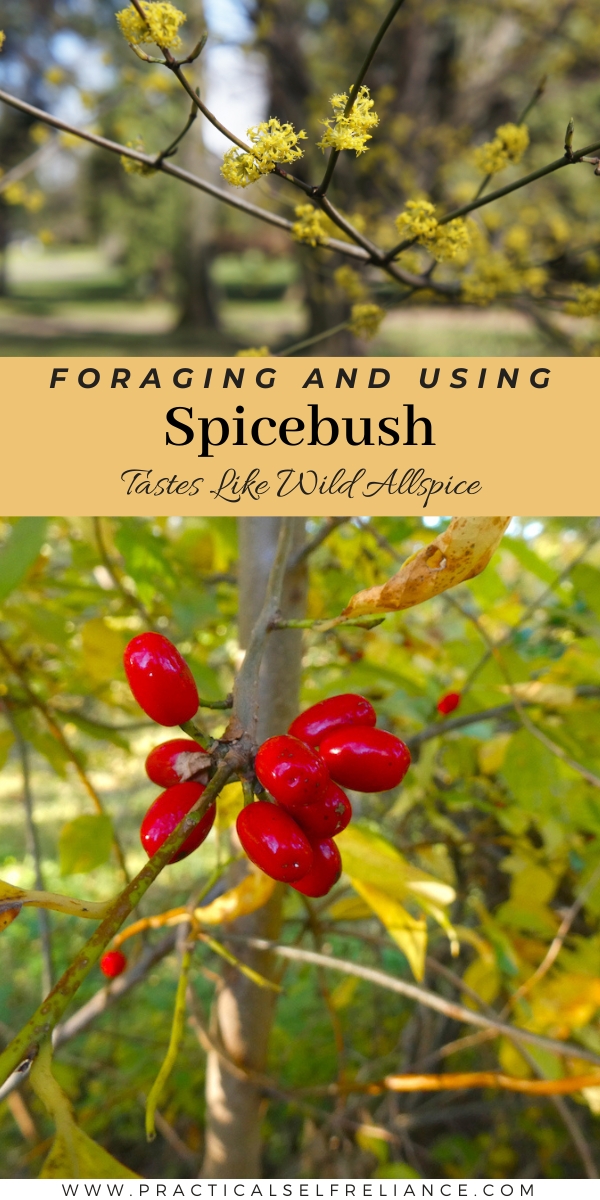

It’s gaining appreciation in gardening circles because of its beautiful spring flowers, which come very early and are as striking as forsythia as they come before the plant leaves in for the year. Forsythia is more common, but it’s not native, and there’s a push by native plant enthusiasts to get more nurseries to carry this easy-to-grow (and delicious) wild plant.

We grow spicebush here on our zone 4 homestead in Vermont. Along with a year-round supply of fruit, our goal is to supply more of our own seasonings right here from our own land. Growing saffron was one of our first steps, then homegrown ginger and even homegrown turmeric. A few years back, we added homegrown spicebush as well.

Even if you don’t have a garden, you can still appreciate spicebush, as it’s readily available in the wild.

While we harvest hundreds of wild edible plants each year, for some reason, I have yet to forage spicebush! Since I’m not an expert on the wild version, I’m happy to share this guide by Marie Viljoen, the author of the book Forage Harvest Feast. At the end, she shares some of her favorite recipes using spicebush as well.

The following excerpt is from Marie Viljoen’s book Forage Harvest Feast (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher. It has been edited slightly for format and length to fit the web.

Spicebush

Other common name: Appalachian allspice

Botanical name: Lindera benzoin

Status: Large shrub, indigenous to

North America

Where: Deciduous woodlands east of the Rockies

Season: All year, fruit in early fall

Use: Spice, aromatic

Parts used: Twigs, leaves, flowers, fruit

Cultivation? Yes, easy to grow

Tastes like: Orange zest and pine with some fresh pepper

Pretty Lindera benzoin bursts into bloom at the end of winter, when the woods are still resolutely brown and pale with dead leaves. Its preferred habitat is in the understory, growing below deciduous hardwoods whose branches remain bare early in the new season. Shimmering with yellow blossoms, spicebush is a harbinger of spring and holds the promise of a new season of flavor.

These North American shrubs or small trees produce an exciting aromatic that remains virtually unknown beyond foraging fringes. I use it more often in my kitchen than familiar cinnamon, or cloves, or allspice. Despite one of its common names (Appalachian allspice), spicebush does not taste like allspice, at least not to me. Instead, it suggests orange peel, with a little fresh black pepper and a backdrop of delicate resin. This throws open a lot of culinary doors. It is as useful in savory applications as it is in sweet baking, dessert making, or drinks.

The most readily used part of the plant is the fruit, appearing on female plants in summer, and ripening in late summer and early fall. It can be used fresh (green and unripe, or ripe and scarlet), or dried and ground. It is an indigenous spice that holds universal potential. It belongs in every working kitchen.

But other parts are edible, too: The marvelous thing about spicebush is that even its winter twigs are intensely aromatic, flavorful enough to use in cooking and infusions. Drop them into a simmering stew, or place them in a jar of sugar; they will imbue both with their citrusy aroma. A fermented cordial of late-winter spicebush twigs and apples is a treat.

Early spring’s little yellow flowers are a delightful raw ingredient, tasting mildly of the fruit to come. Where the shrubs are prolific, it is easy to gather a couple of handfuls by stripping the blossoms from a branch on different individuals. Never denude one shrub. It’s just rude. When the leaves appear, their flavor is slightly stronger. Add them to ephemeral spring salads while they are tender and chewable. By summer the spicebush shrub has retreated into green, inconspicuous anonymity. I identify it easily now, but I used to stop to scratch its summer twigs, to make sure I had the right plant. It is a refreshing scratch-and-sniff stop on the forage walks I lead. Later, small branches with mature leaves add flavor to grilled meats or infusions. And then the main event: the fruit. Midsummer’s green drupes on female plants are brightly flavored, and by late summer they have ripened to brilliant crimson. Both stages are useful, with distinctive aromas.

While delicious fresh, the fruit should be dried and then frozen to use throughout the year. It maintains its flavor exceptionally well. I grind mine as needed, using a spice grinder. For those who live beyond the range of spicebush, or whose local spicebush populations are meager, this unique American flavor is within reach via the Internet. Integration Acres, based in Ohio, sells packages of the dried fruit, and the quality is excellent.

Spicebush could be on everyone’s spice rack. It should be. Grow your own, if you have the space. The small trees are good additions to semi-shady gardens, and their presence will help boost local biodiversity.

How to Forage Spicebush

There are many different edible and useful parts of spicebush. Here’s how to prepare each one…

Spicebush Twigs

Use a sharp, clean knife or pruning shears and cut above a leaf node. Twigs flavor stews, infuse liquors, and also perfume sugar, like a vanilla bean.

Spicebush Flowers

Strip them from a branch and collect them in a small paper bag. At home keep them covered in the fridge. Limit your stripping to a couple of branches per shrub.

Spicebush Fruit

Once picked, the fruit—especially the unripe green drupes—darkens quickly, although the flavor remains intact.

Dry the fruit by spreading it out loosely on parchment paper and either air-drying over several days or dehydrating in a dehydrator or in the oven, using the lowest setting—200°F (93°C) or lower. If you use the oven method, turn the oven off after 30 minutes, leave off for 1 hour, then on again for 30, until the fruit is dry. You do not want to roast it.

Freeze the dried fruit in airtight bags or small jars. It keeps its flavor exceptionally well in the freezer. Grind it up as needed.

Growing Spicebush

USDA Hardiness Zones 4–9

If the goal is fruit, both male and female shrubs are needed. The flowers on males are showier, and only the females carry fruit. Spicebush prefers moist but well-drained soil and will grow in high shade, semi-shade, or full sun. It is tolerant of acidic and slightly alkaline soils. The fruit provides food for birds, and the shrub is the exclusive host for the larvae of the spicebush swallowtail butterfly.

Spicebush Recipes

Spicebush is incredibly versatile and can be used as a seasoning just about anywhere. Here are a few spicebush recipes to get you started!

Spicebush Cranberry Syrup

Makes 3 cups (750 ml)

When local cranberries flood the markets, I make this easy and festively crimson syrup for holiday cocktail shaking. (You can also make a cold-extraction cranberry syrup—with the bonus of the leftover, candied fruit—by following the recipe for Fermented Serviceberry Syrup—just add spicebush and make sure to crush the cranberries, which have thick skins.)

- 12 ounces (340 g) cranberries, crushed

- 6 ounces (170 g) sugar

- 1 tablespoon ground spicebush

- 3 cups (750 ml) water

Place the cranberries, sugar, spicebush, and water in a pot over medium- high heat. Bring the liquid to a boil, then reduce the heat to a simmer and cook for 10 minutes. Turn off the heat and let the mixture cool. Strain twice through cheesecloth, bottle, and keep in the fridge. It lasts well for 1 month. Use the fruit to garnish drinks like Wild Sweetfern and Citrus Toddy.

Spicebush Cranberry Fizz

Makes 5 cups (1¼ liters)

This ferment has a strong spicebush presence and blends beautifully with applejack, bourbon, whiskey, dark rum, and tequila. It also has a great affinity for apple cider, citrus, ginger, and tea. Think hot toddies (such as Thaw and Wild Sweetfern and Citrus Toddy). Use it to deglaze a roasted carrot pan, and add it to tropical fruit salads. Because cranberries ferment slowly I add apples to my mixture to help the yeasts along.

- 12 ounces (340 g) cranberries, lightly crushed

- 1/2 apple, cut up (not peeled or cored)

- 1 cup (200 g) sugar

- 1/4 cup (30 g) ground spicebush

- 5 cups (11/4 liters) water

Place the fruit in a clean jar. Add the sugar and spicebush, and top with the water. Stir well. Cover the jar’s mouth with cheesecloth and stir daily. Small bubbles rising after a day or two are a sign of fermentation. After the bubbles have been active for 5 days, strain the fruit from the liquid through a fine-mesh strainer and again through double cheesecloth. Bottle the strained liquid and keep it in the refrigerator until needed.

Long Nights

Makes 1 drink

Winter’s impenetrable nights inspire dark drinks.

- 2 1/2 fluid ounces (5 tablespoons) bourbon

- 1 fluid ounce (2 tablespoons) Spicebush Cranberry Fizz

- 1 fluid ounce (2 tablespoons) dry sherry

- 2 teaspoons pomegranate molasses

Combine all the ingredients with ice in a cocktail shaker. Shake, strain, and pour.