Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

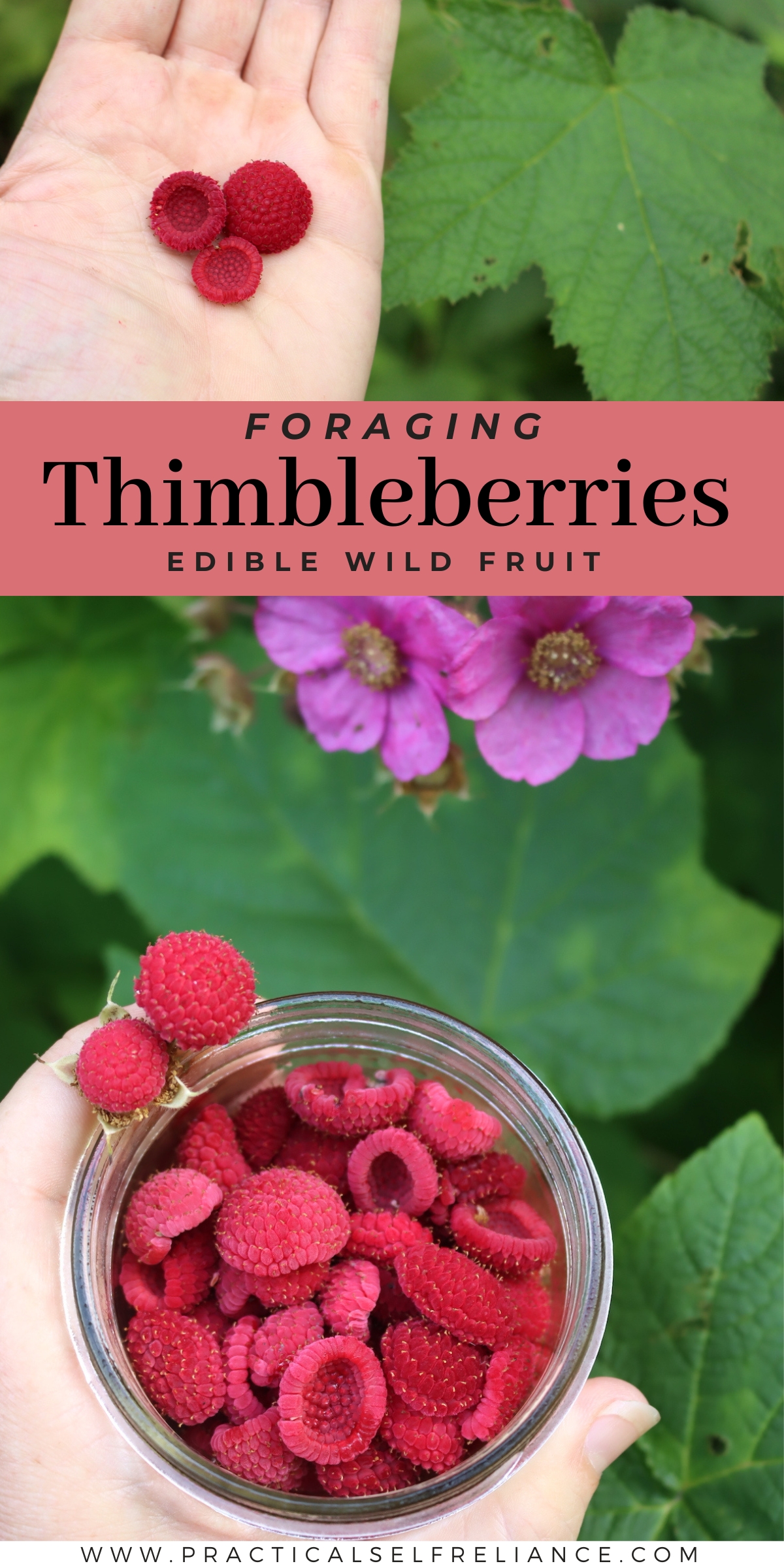

Thimbleberries are a delicious species of wild flowering raspberry, and there are varieties that grow wild in both the Pacific Northwest and the Northeast.

If you’ve ever wandered through the woods in late summer, you might have caught a glimpse of a sweet, berry-like fruit hanging from arching, thornless brambles. You may have even tasted one and instantly fallen in love with its unique, sweet-tart flavor that tastes more like a raspberry than a raspberry.

It’s like a raspberry-flavored candy, and the flavor is so lush that it almost tastes artificial.

That fruit is the thimbleberry—an often-overlooked wild delicacy that’s as rewarding to forage as it is delicious.

Western Thimbleberries (Rubus parviflorus) grow across North America, from the Pacific Northwest to the eastern woods of the United States. There’s another similar berry in the northeast, which the locals also call Thimbleberry (Rubus odoratus), and that one is almost identical but has pink flowers instead of white.

Both species are known for their delicate, bright red color and soft, almost velvety texture, they’re easily mistaken for raspberries, but they have their own distinct almost more raspberry than raspberry flavor. And, they’re thimble shaped too!

What are Thimbleberries?

Thimbleberries are perennial, fruiting shrubs in the Rubus or Raspberry genus. Thimbleberries are native to North America, and there is a western type, Rubus parviflorus, and an eastern type, Rubus odoratus.

You may also hear folks refer to the western Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) as Redcap or Salmonberry though they are not the true Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis). The eastern Thimbleberry (Rubus odoratus) is also called Purple-flowering Raspberry, Flowering Raspberry, or Virginia Raspberry.

Various cultivated varieties of each species are available, and gardeners often use them in ornamental shade gardens. Rubus odoratus has also naturalized in parts of Europe, especially East England.

Are Thimbleberries Edible?

Yes, Thimbleberries are edible and a safe plant to collect and enjoy. The berries are highly prized wild edibles, making an excellent snack while hiking or cooked like the closely related raspberries.

The young shoots are also edible and safe, cooked or raw. Most frequently, foragers cook them like asparagus.

Like other members of the Rubus genus, the leaves though not a choice edible, are often gathered by herbalists for use in internal and external remedies. The roots and young shoots are also sometimes employed in traditional medicine.

Avoid harvesting Thimbleberries along roadsides where they could be contaminated with car exhaust and other chemicals.

The use of Thimbleberry leaf tea and other preparations hasn’t been widely studied in people who are pregnant or nursing. Some herbalists recommend leaf tea of members of the Rubus genus, like Red Raspberry, to aid in labor. However, some studies have shown that they may help by softening the cervix and inducing labor and, therefore, should be avoided during early pregnancy. While we don’t know if this is true for Thimbleberry, you should still avoid Thimbleberry preparations while pregnant or breastfeeding until you consult your physician.

Thimbleberry Medicinal Benefits

While many foragers pick Thimbleberries for the flavor, they also pack a nutritional punch. Thimbleberries are high in Vitamins A and C, and historically, both Native Americans and settlers ate them to treat scurvy.

Native Americans employed Thimbleberries in their traditional medicine. Some groups used the fresh leaves to create poultices or decoctions for treating acne. They would also make a powder from the dried leaves to treat wounds and burns. The Quileutes also chewed the bark and spit it into wounds especially burns to clean them. The Makah pounded the bark and used it to treat toothaches or festering wounds.

Native Americans also used the leaves, roots, and shoots to make teas for treating various ailments, including nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and dysentery. The Quileutes also boiled the bark in seawater and used this drink to lessen labor pains.

Today, herbalists often employ Thimbleberry leaves to boost the appetite and treat various stomach ailments. The leaves are believed to have astringent, antiemetic, stomachic, and blood-cleansing properties. Occasionally, people will incorporate the roots and leaves into cosmetics and other external preparations to treat acne, heal irritated skin, and prevent scarring.

Modern medical research hasn’t spent much time focusing on Thimbleberry remedies. However, one study found that the tannins in the western Thimbleberry (Rubus odoratus) have anti-tumor properties.

Generally, herbalists also use Thimbleberries in many of the same remedies as they would other members of the Rubus genus, such as Red Raspberries, Blackberries, and Black Raspberries. People worldwide began using different species of Rubus for food and medicine shortly after the Ice Age.

Where to Find Thimbleberries

Thimbleberries are native to North America but have naturalized in parts of Europe, especially East England. You can find Rubus parviflorus in the western region of the United States, east to the Rockies, and in patches as far east as the Great Lakes. Rubus odoratus is found in the eastern United States, particularly along the Appalachian Mountains.

Thimbleberries of both species thrive in areas with cool, moist summers. They often grow along forest edges, open woodlands, or newly cleared land after logging or forest fires. Frequently, Thimbleberries pop up on sloped edges like road banks, trail edges, and the sides of railroad tracks.

Thimbleberries can grow in shade to full sun but prefer acidic, moist soils. They grow best in sandy, gravelly, or loamy soils.

When to Find Thimbleberries

Thimbleberries are perennial and present year-round but deciduous, meaning they drop their leaves in the fall. The brownish canes that remain over winter can be tough to spot and identify.

They begin to leaf out in early spring, around the same time as many other deciduous trees, and then flower soon after. They will flower and fruit over a long period, and depending on your location, you may spot Thimbleberries blooming from May to August.

Identifying Thimbleberries

Thimbleberries are one of those plants that’s easy to overlook along the sides of roads and trails you regularly use until they have fruit. Then, you may spot its red berries that look very similar to raspberries.

These shrubs also have a similar form as many other Rubus or raspberry species with long arching canes. However, their leaves are a bit different. While most Rubus species have compound leaves, Thimbleberry’s are simple and palmate, looking more like maple leaves.

Both species of Thimbleberry taste and look similar. The major difference is their flowers. Rubus odoratus has very fragrant, pinkish-purple blooms rather than white like many Rubus species, including Rubus parviflorus, making it especially easy to pick out. Compared to other Rubus species, both Thimbleberries have relatively large blooms.

You’ll often spot Thimbleberries growing in large patches as they can spread through underground rhizomes allowing them to cover an area and outcompete other plants quickly.

Thimbleberry Leaves

Thimbleberries have soft, green, palmate, aromatic leaves. The leaves resemble the leaves of maples in shape and typically have between three and seven lobes.

The leaves are much larger than most other Rubus species and can be up to 10 inches long and across.

Thimbleberry Stems

Thimbleberries grow large arching canes about ½ inch in diameter and up to 10 feet tall. The canes are thornless, covered in brown, reddish-brown, yellowish, or grayish bark.

Some of the bark may begin to crack and peel on older canes, revealing whitish underneath. New shoots and stems may be green. Young canes have short, reddish, bristly hair.

Thimbleberry Flowers

Thimbleberry’s flowers help set them apart from other Rubus species. They’re comparatively large and may be ¾ to 2 ¼ inches in diameter. Each flower has five petals and a yellow center.

In Rubus parviflorus, these petals are white, while in Rubus odoratus, the petals are pink, pinkish-purple, or magenta. Rubus ordoratus flowers are also very fragrant.

Thimbleberry Fruit

Thimbleberries get their name from their hollow-centered fruits, which are fun to stick over the tips of fingers for kids and adults alike. They look a bit like raspberries but are more broad and shallow.

The berries are soft, almost velvety, usually about ½ inch in diameter, and ripen to bright red or purplish.

Thimbleberry Look-Alikes

The western Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) is sometimes mistaken for another western Rubus species, Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis). However, Salmonberry differs in several noticeable ways:

- Salmonberry canes, particularly the young ones, are prickly.

- Salmonberry has compound, trifoliate leaves that are made up of three separate leaflets.

- The leaves are smooth to slightly hairy on the top surface.

- Salmonberry flowers have pinkish-purple petals (remember that Rubus parviflorus flowers are white) surrounding a cluster of stamens.

- Salmonberries are long and shiny and ripen to red or yellow-orange.

Another lookalike is the American Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeusvar. strigosus). Fortunately, it too differs in a few easy-to-spot ways:

- American Red Raspberry has large, compound leaves that typically have three to five leaflets. Occasionally they have seven leaflets.

- American Red Raspberry canes are purplish-red and have sharp prickles.

- American Red Raspberry flowers are white and form in loose clusters.

- American Red Raspberries are shiny, red, and rounded.

Thimbleberry can also be confused with the Stink Currant (Ribes bracteosum) with its similar-looking leaves. Thankfully, it too can be easily distinguished with the following traits:

- The entire Stink Current plant, including the leaves, is sprinkled with yellowish glands that emit a sweet-skunky odor that gives the plant its name.

- The leaves are stinky when crushed.

- Stink Currants produce 6 to 12-inch long racemes or inflorescences of 20 to 40 white to greenish flowers.

- Stink Currant berries form in long clusters and are round and blue with a whitish bloom.

Lastly, Thimbleberry can be mistaken for Devil’s Club (Oplopanax horridus). Devil’s Club is distinguished from Thimbleberry in the following ways:

- Devil’s Club can reach a height of 10 to 16 ½, though it may stay much smaller.

- Devil’s Club flowers are small, greenish-white, and form in dense umbels up to 8 inches in diameter.

- Devil’s Club stems, and leaf veins on the upper and lower leaf surface are covered in irritating brittle yellow spines.

- Devil’s Club berries are roundish and form in large cone-shaped clusters at the tops of the stems.

Ways to Use Thimbleberries

The easiest way to use Thimbleberries is to enjoy fresh berries straight from the bush. They make excellent trailside snacks or toppings for granola, yogurt, or salads. Thimbleberries are also excellent cooked. You can use them to make delicious jams, cobblers, muffins, and other baked goods.

Unfortunately, Thimbleberries produce berries slowly throughout the summer, rather than all at once. While this is excellent for fresh eating, it makes it tough to gather enough for many recipes. However, they’re excellent blended with other wild berries and homegrown fruits in applesauce, preserves, pie fillings, fruit leather, or pemmican.

On the off chance that you have more than you can use fresh, you can preserve Thimbleberries. You can freeze them, dehydrate them, or can them.

Young Thimbleberry shoots also make for a tasty snack. Like the berries, you can eat the shoots fresh or raw. They’re a bit asparagus-like and are an excellent steamed or sauteed vegetable. Throw them into stir-fries, omelets, or quiches.

Thimbleberry can also be a helpful plant to add to your herbal medicine practice. The large soft leaves are wonderful for stomach ailments and digestive issues. Harvest the leaves to make decoctions, teas, and tinctures. You can use the roots and shoots similarly. Preserve some of the roots, shoots, and leaves for later use in tea or other herbal preparations by dehydrating them.

You can also try using Thimbleberry leaves, roots, and shoots in external preparations. Herbalists believe Thimbleberry may have soothing and healing effects on minor wounds, burns, acne, and other skin issues. Try incorporating Thimbleberry leaves into poultices, salves, or herbal soaks.

Thimbleberry has a few non-culinary and medicinal applications too. Hikers and woodland wanderers sometimes find that the soft leaves make excellent emergency toilet paper. Fiber artists have also employed Thimbleberries to create a natural, dull blue dye.

Thimbleberry Recipes

- Make a special treat with this Thimbleberry White Chocolate Chip Cookies recipe from Hilda’s Kitchen Blog.

- If you’re more of a cake person, try this Sugar-Kissed Vanilla Berry Cake from the Art of Natural Living with Thimbleberries or a combination of foraged berries.

- Have extra Thimbleberries? Preserve them with this simple 3-Ingredient Thimbleberry Jam from Creative Canning. You can water bath can it, freeze it, or keep it as a refrigerator jam.

- Once you’ve got some jam, you can make a quick snack for on-the-go with this Thimbleberry Bar recipe from Girl Gone Grits.

- If you’d like to use Thimbleberry medicinally, try getting started with this video for making Thimbleberry leaf tea from GabNaturalist.

Edible Brambles

Looking for more delicious bramble fruit out there in the wild?

I live in the Pacific NW. I know you mentioned it but they make excellent wild TP. My kids call it the TP plant. Aside from that, a ripe thimbleberry warmed by the sun is one of the best treats ever!