Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

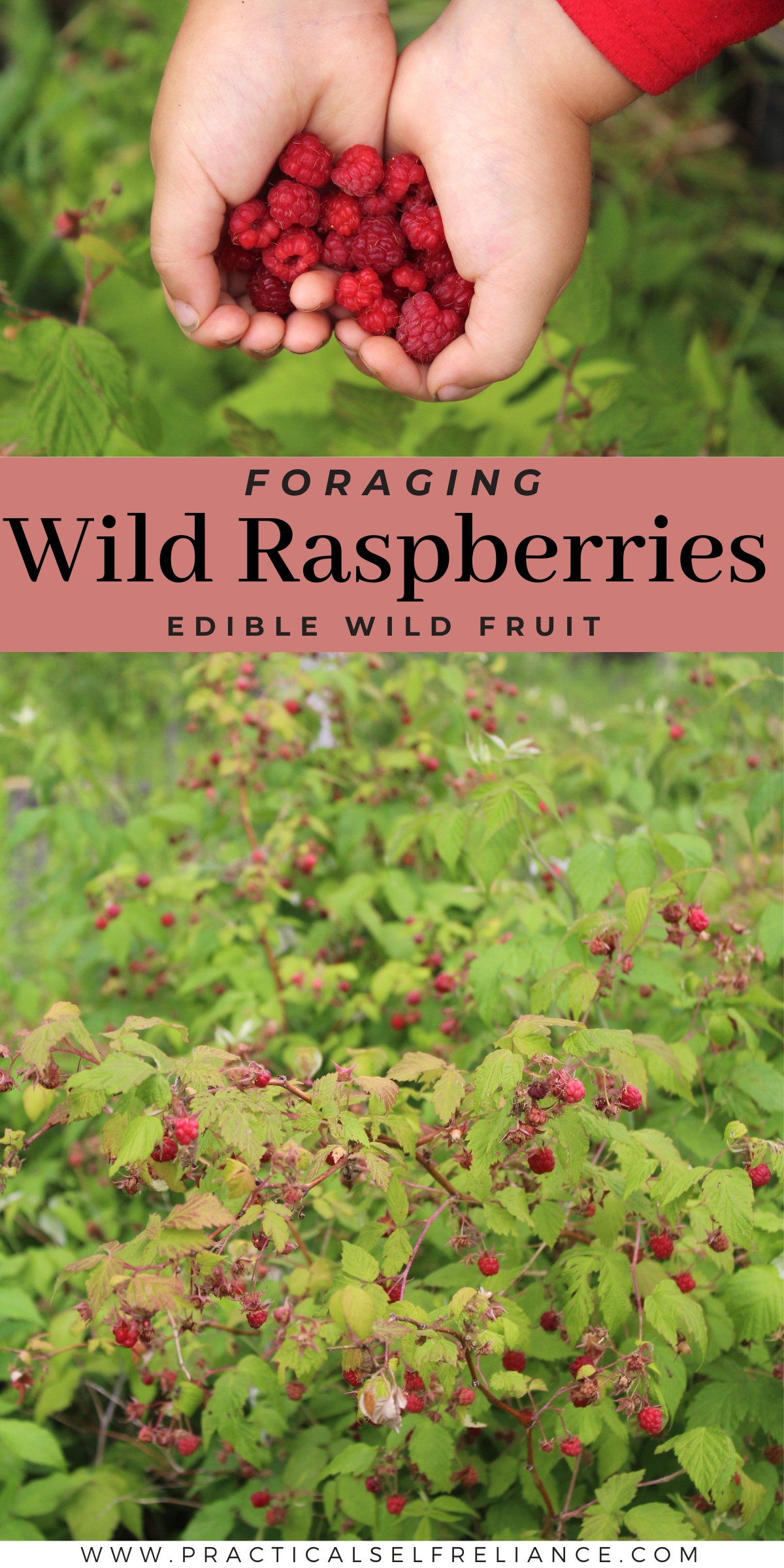

Wild Raspberries (Rubus sp.) are the same grocery store fruits you find for a hefty price tag, but they’re free! These easy-to-identify edible wild berries are everywhere; you just need the confidence to identify and harvest them yourself.

Wild raspberries are one of the easiest wild edible fruits to forage. They’re delicious, and they don’t have any toxic look alikes.

Pretty much everything that looks like a raspberry is either a raspberry or another closely related edible rubus species. Listing them all off makes me feel a little bit like Willy Wonka, and while there aren’t scnhozberries, there are thimbleberries, salmonberries, black raspberries, and red blackberries. All of them look vaguely like raspberries, but they’re all also delicious and edible (and there are many more, dozens of species in the US alone).

While raspberries are easy to ID, you do still need to identify them to harvest them safely. I’ll walk you through everything you need to know to forage wild raspberries successfully.

What are Raspberries?

Raspberries are perennial, fruiting shrubs in the Rubus genus of the Rose or Rosaceae family. There are many raspberry species, and they are native to parts of Asia, North America, Australia, and Europe. Many of these species have naturalized well outside of their native range.

Raspberry species native to North America include Whitebark Raspberry (Rubus leucodermis), Rocky Mountain Raspberry (Rubus deliciosus), Black Raspberry (Rubus occidentalis), Thimbleberry or Purple-flowering Raspberry (Rubus odoratus), Snow Raspberry (Rubus nivalis), Arctic Raspberry (Rubus arcticus) and American Red Raspberry (Rubus strigosus).

The European Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) is also commonly cultivated in North America and has naturalized in some areas.

Are Raspberries Edible?

You’re probably already familiar with raspberries for their tasty, edible fruit. They’re easy to use raw or cooked, even for the beginner forager.

While all of the raspberries are edible, some species aren’t quite as tasty as others. The berries of Rocky Mountain Raspberry (Rubus deliciosus) tend to be dry with lots of seeds.

The leaves are also edible and make a tasty tea. The leaves also have medicinal benefits, and herbalists frequently use them in internal preparations. Herbalists also use the roots of some raspberry species to make teas, tinctures, and poultices.

It’s not just humans that benefit from raspberry leaves. They’re a helpful herb for the natural care of animals like dogs, horses, goats, and rabbits.

Raspberry leaves are often employed to aid in labor and help with menstrual issues. As they may affect the reproductive system, you may want to consult your midwife or physician before using raspberry leaves if you’re pregnant.

Raspberry Medicinal Benefits

Raspberries have been part of human life for thousands of years. Archeological evidence suggests that humans were eating raspberries as early as the Paleolithic era, and our first evidence of domestication comes from Roman agricultural writer Palladius in the 5th century. People may have first used raspberries for their tasty fruit, but they also quickly incorporated the plant into herbal medicine.

The ancient Indians, Greeks, Chinese, and Romans all used raspberry leaves in their traditional medicinal practices. They used the leaves to treat wounds and diarrhea and as a childbirth aid for both humans and livestock.

Culpeper’s Complete Herbal, published in 1653, displays the continued use of raspberry leaf through the ages. Culpeper writes about raspberry leaf as “very binding and good for fevers, ulcers, putrid sores of the mouth and secret parts, for stones of the kidneys and too much flowing of the women’s courses.”

People in the Americas were also using raspberry medicinally. The Cherokee, Iroquois, and Mohawk people all used raspberry leaves to help with labor by easing labor pains and contractions and soothing nausea. Undoubtedly, other Native American groups used the plant as well.

In modern times, herbalists recognize that consuming both the berries and leaves may help to support general wellness and the immune system. The berries are full of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and fiber. The leaves also contain significant amounts of vitamins B, C, and E and essential minerals like calcium, magnesium, and zinc. In addition, the leaves are high in antioxidants that may help protect the body from cancer and disease.

Modern medicine has also recognized raspberry leaf extract as a treatment for some mouth sores. An Australian study found that the extract was a safe and effective treatment for Oral lichen planus (OLP), a chronic mucocutaneous inflammatory disease. The study found that using raspberry leaf extract significantly reduced OLP symptoms, including “burning sensation, reticulation, erosion, and ulceration.”

Increased antibiotic-resistant bacteria has led some modern scientists to experiment with raspberry leaves for infections, too. A 2023 study found that a combination of tormentil, raspberry leaves, and loosestrife extracts made a suitable antibiotic replacement for treating campylobacteriosis, a common food-borne illness from undercooked poultry.

Today, many herbalists and midwives continue to use raspberry leaf products to help with labor and menstrual issues. One study from The Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health found that raspberry leaf tablets reduced the second stage of labor by almost 10 minutes and resulted in a lower rate of forceps deliveries.

However, on the whole, raspberry leaf products have been largely understudied for women’s issues. Disappointingly, some studies still regularly cited for raspberry leaf’s use in women date back to as early as 1941.

Where to Find Raspberries

Raspberries grow throughout most of North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Some species, like the American Red Raspberry (Rubus strigosus) and the naturalized European Raspberry (Rubus idaeus), are widespread in the United States. Meanwhile, other species, like the Rocky Mountain Raspberry (Rubus deliciosus), have a more limited range.

Raspberries are early succession species that quickly colonize open or disturbed habitats like abandoned fields, clear-cuts, roadsides, and the edges of railroads, lakes, streams, and meadows. They thrive in the full sun to partial shade that these habitats offer.

Raspberries are pretty tolerant of different soil types, but you’re most likely to find them thriving in places with well-drained, acidic soil.

When to Find Raspberries

Raspberries are deciduous perennials. Like deciduous trees, they lose their leaves in the fall, but you may still find their arching canes year-round.

Most herbalists recommend harvesting the leaves in spring or early summer before the plants flower and begin to produce fruit. Some foraging experts and herbalists believe the leaves are higher in sugars and healthy compounds at this stage before they have put energy into flowering.

Raspberries flower in late spring or summer and fruit in summer or early fall, depending on the region. Plants in southern regions usually fruit first, sometimes in June, while plants in northern areas often don’t fruit until late July, August, or September.

Identifying Raspberries

Raspberries form drooping or arching canes that sometimes root where they touch the ground to form new plants. While they do spread to create patches, they generally aren’t as aggressive as most blackberry species.

They have pinnately compound leaves, which can be challenging to differentiate from other species like blackberries. However, their hollow-centered berries that pull easily off the bush when ripe are a dead giveaway.

Raspberry Leaves

Raspberries have compound, alternately arranged leaves with three to five or rarely seven leaflets. The leaves are each held on small petioles or stems.

The leaflets are usually ovate with pointed tips and serrated margins and are 1 to 4 inches long. They are green above and hairy and pale below.

The Purple-flowering Raspberry (Rubus odoratus), sometimes called thimbleberry, stands out among the raspberries for its large palmate leaves up to 10 inches wide and long.

Raspberry Stems

Raspberry stems may be greenish, purplish, brownish, or reddish. Typically, they’re covered in stiff bristles and hairs, though some species have more pronounced thorns. Usually, raspberry canes grow from 2 to 10 feet tall but tend to arch or droop over rather than stand erect.

Some species have more noticeable variation. Black Raspberry (Rubus occidentalis) canes display a noticeable whitish bloom. Purple-flowering Raspberry (Rubus odoratus) has thornless canes with red, bristly hair when young and peeling and cracking bark in their second year. The Rocky Mountain Raspberry (Rubus deliciosus) is also thornless, and the Arctic Raspberry (Rubus arcticus) only grows about 12 inches tall.

While raspberries are perennial, their canes are mostly biennial. The root system lives for many years, but each cane only lives for two years. The first-year canes are called primocanes and tend to be prickly and covered with bristly hair and glands. The second-year canes are called floricanes and are similar to primocanes but may also have spines. These two-year-old canes produce flowers and fruit.

The canes may root where they touch the ground and grow new plants.

Raspberry Flowers

Raspberry flowers usually grow in small groups of three to five. Each flower is usually about 1 cm wide and has five reflexed sepals and five white, rounded petals.

A few raspberries have different features, though their flowers still share basic characteristics. For example, the Purple-flowering Raspberry (Rubus odoratus) has larger, purplish, or magenta flowers that are 1.2 to 2 inches wide, and the Rocky Mountain Raspberry (Rubus deliciosus) has fragrant white flowers about 2 ½ inches wide.

Raspberry Fruit

After flowering, raspberries form hollow-centered, rounded clusters of fleshy drupes typically about ½ inch wide. The fruit of the Purple-flowering Raspberry (Rubus odoratus) tends to be more flattened than the other raspberries.

Depending on the species, these fruits usually ripen from green to red or dark purple. Some species, like the American Red Raspberry (Rubus strigosus), have tiny hairs on the fruit, while others, like the Black Raspberry (Rubus occidentalis), have a whitish bloom on the fruit.

Raspberry Look-Alikes

Raspberries are easy to confuse with other members of the Rubus genus, like The Pennsylvania Blackberry (Rubus pensilvanicus). However, they have a few key features that set them apart:

- Pennsylvania Blackberry canes mature from green to dark red.

- Pennsylvania Blackberry canes are usually ridged and covered with copious amounts of straight prickles.

- Blackberries have a soft green or white center rather than being hollow.

If you live in an area with alpine areas, boreal forests, or arctic tundra, you may also spot Cloudberries (Rubus chamaemorus), sometimes confused with raspberries. However, they are easy to tell apart in the following ways:

- Cloudberries only grow 4 to 10 inches tall.

- Cloudberries have soft, palmate leaves with 5 to 7 lobes.

- Cloudberries start as pale red and then ripen to amber.

Occasionally, raspberries may also be confused with Mulberries (Morus spp.). However, there are several easily observed ways to differentiate them:

- Mulberries are fast-growing trees that may reach 80 feet tall.

- Mulberry leaves are simple and alternately arranged.

- Mulberries have a green or white center rather than being hollow.

All of these are edible wild fruits as well.

Ways to Use Raspberry

Raspberries are easy to enjoy right off the bush. They make an excellent trailside snack for hikers! If you’re fortunate enough to find a large patch, there are plenty of great ways to use them at home. To preserve berries for use over the winter, you can dry, freeze, or can them as jam. Mashed raspberries and other fruits make tasty fruit leathers for kids and adults.

Their sweet, slightly tart flavor makes them great toppings for salads, cereal, and cakes. Surprisingly, they’re also a tasty addition to more savory creations like rib glaze, meatballs, or pork chops.

You can also use them in baked goods. Make raspberry muffins, cobbler, granola, pie, crisp, cake, cheesecake, or quick bread. They’re also easy to add to other dessert recipes like chocolate bark, ice cream, smoothies, and popsicles.

Additionally, raspberries are great drink ingredients. Try making raspberry lemonade, simple syrup, or your own signature raspberry cocktail or mocktail recipe.

If you want to add raspberry to your herbal practice, you’ll want to harvest the leaves in spring or early summer. Then, you can use the leaves fresh or dry them for later use. Raspberry leaves are wonderful medicinal herbs that are great for making teas, tinctures, or mouthwash to help treat infections, mouth sores, menstrual issues, diarrhea, and digestive problems.

Thankfully, leaves make one of the best-tasting herbal teas. Not surprisingly, they were one of the herbs that saw heightened use just before the American Revolution as Americans gave up true tea leaves to protest the Tea Tax.

You can also powder the dried leaves and put the powder in capsules or add it to smoothies and other dishes.

Lastly, you can experiment with raspberry roots. You can make root teas and tinctures for digestive issues, mouth sores, and diarrhea. Or you can pound the roots and use them externally as a poultice for soothing minor wounds, burns, and skin irritations.

Raspberry Recipes

- Wild raspberries work wonderfully in a homemade raspberry wine.

- Raspberry jelly is a simple recipe that comes together without added pectin. Just sugar and fruit!

- Check out this Chipotle Raspberry Chicken Thigh recipe from Handle the Heat for a savory take on raspberries.

- These Sheet Pan Pork Chops with Raspberry Ketchup from Healthy Seasonal Recipes are easy to make and easy to eat.

- Encourage your kids or friends to fall in love with foraging with these Raspberry Popsicles with Dark Chocolate Drizzle from Foraged Dish.

- Simple, raspberry leaf tea is nourishing and easy to make. Miracle Cord has six great raspberry leaf tea recipes depending on your tastes and needs.

- Create a raspberry leaf tincture with this recipe from Susan of The Sparrow’s Home. She highly recommends this recipe for folks who struggle with painful periods and other menstrual issues.