Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

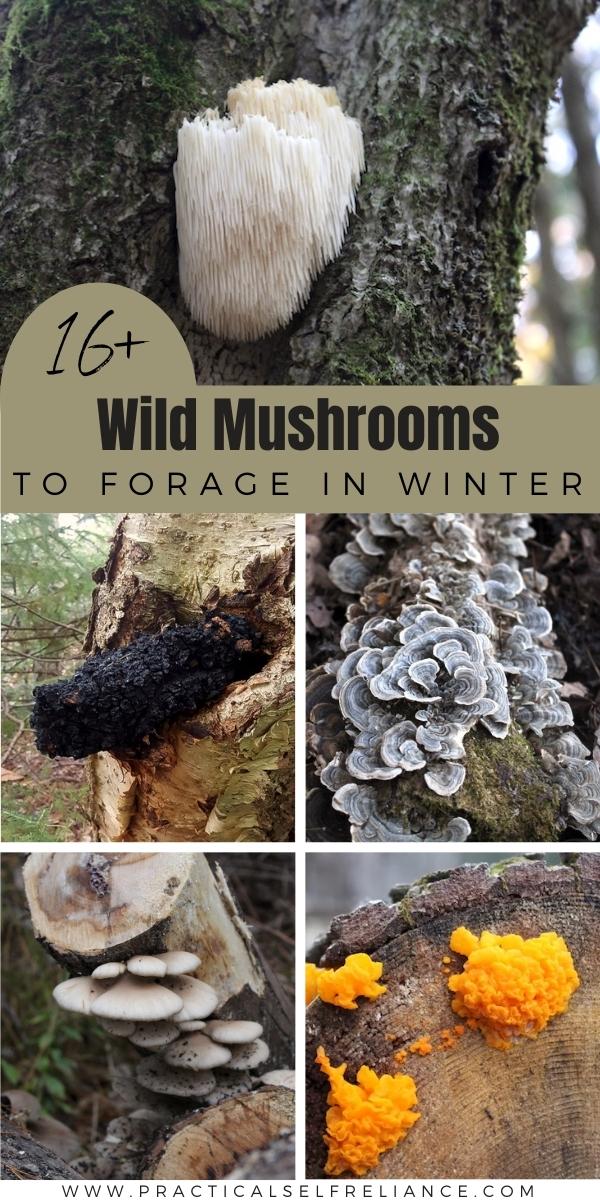

Winter mushroom foraging? Really? Yes! Some mushrooms grow year-round, and others just prefer the cold temperatures of winter and early spring. Learn which mushrooms thrive in the snow and you’ll be able to forage mushrooms year-round.

Mushroom foraging sounds like a warm-weather hobby, and for the most part, it is. Many of the prized edible mushrooms come out during the warmer months, and some, like morels, actually need specific soil temperatures to appear.

Some mushrooms, however, actually thrive in cold weather, and just won’t sprout until temperatures drop. Others, known as perennial mushrooms grow year-round, and it’s actually better to harvest them in the winter when the trees are dormant.

Either way, there are quite a few mushrooms to forage in winter, even in cold climates.

At this time of year, there’s not a lot going on, and it’ll be a while until maple syrup season, and many more months before we start our seedlings. Winter mushroom foraging is a great reason to get outdoors in the cooler seasons.

Here in Vermont, we put on snowshoes and trek through the snow for our finds, but in warmer latitudes or out west, you’ll be able to take a cool-season hike to enjoy what nature has to offer without heat, humidity, and summer insects.

While you’re out there, keep an eye out for all the other things you can forage in winter, from lichen to pine needles, bark, and even berries that hang on branches all winter. Nannyberries, highbush cranberry, barberry, rose hips and partridgeberry are just a few examples, but there are dozens that ripen after the birds have migrated for the season. They hang on branches all winter, sweetening all the while, waiting for the birds to arrive in spring (or adventurous foragers to find them in the cold months).

Winter greens, as well as edible roots and tubers also hide beneath the snow just waiting to be found. People lived this land year-round without grocery stores not all that long ago, and winter didn’t necessarily mean living on stored foods. There’s plenty to find in the winter landscape if you know where to look.

Winter Mushrooms

Each of these mushrooms is available during the winter months, though the exact season is going to vary based on your climate. Many are potent medicinals, but others are tasty edibles. Some are even both.

Just about all of them sell for high prices in stores and online, so you’ll save a pretty penny learning to identify them yourself.

Besides their edible and medicinal qualities, many of them were also used for other uses historically. Some are used for fire starting, and others can even be made into high-quality clothing. Mushroom leather is still a thing in many parts of the world, and processing it can be a fun way to spend the winter by the fire, and give you functional and beautiful to wear at the same time.

Winter Mushrooms in the Northeast

I’ll take you through each of these winter mushrooms one by one, but here’s my list of mushrooms that grow in winter, in the northeast and other cold climates:

- Chaga (Inonotus obliquus)

- Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor)

- Birch Polypore (Fomitopsis betulina)

- Tinder Polypore (Fomes fomentarius)

- Witches Butter (Dacrymyces palmatus)

- Enoki (Flammulina velutipes)

- Lion’s Mane (Hericium sp.)

- Winter Oysters (Pleurotus sp.)

- Artist’s conk (Ganoderma applanatum)

- Red-belted polypore (Fomitopsis pinicola)

- Amber jelly roll (Exidia recisa)

- Black Jelly Roll (Exidia glandulosa)

- Wood ear (Auricularia angiospermarum)

- Brick caps (Hypholoma sublateritium)

Though these are a particular novelty as winter mushrooms in the northeast, when other pickings are generally sparse, they also grow during the coldest part of the year in warmer climates. I’ve foraged most, but not all of these, and for the last few, I’ll refer you to resources from others who know them better.

Winter Mushrooms for Warmer Locations

Locations like the Pacific Northwest, South, and West have warmer winter temperatures and snow is rare, in those regions, there are even more mushrooms to forage in winter, including:

- Yellowfoot Chanterelle (Craterellus tubaeformis)

- Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus cornucopioides)

- Hedgehog Mushroom (Hydnum repandum)

- Candy Cap (Lactarius sp.)

In Vermont, most of these are either spring or late fall mushrooms, as our “shoulder seasons” are about equivalent to winter in the west and south. I realize that’s where most of the population of the US lives, so I mention them because not everyone lives in the frozen north!

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus)

Some of the best known medicinal mushrooms, chaga fungus grows specifically on birch trees. It’s parasitic, and will slowly kill the tree over the course of a few decades.

Birch trees are medicinal trees, and they have a number of compounds in their tissues to defend themselves from mushroom invaders. The mushrooms in turn make compounds to survive in the birch wood. As luck would have it for humans, the compounds both in beech wood and in chaga mushrooms that they produce for their survival happen to have a range of medicinal benefits for people.

Studies show that chaga mushrooms are anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory, and they’re used to:

- Reduce Cholesterol

- Lower Blood Pressure

- Ease Arthritis Pain

- Fight Cancer

- Slow the Aging Process

Chaga fungus is dense and woody, and it’s best harvested with an axe during the winter months when the tree is dormant. This helps prevent damage to the birch tree, though if it’s infected with chaga its days are numbered anyway.

Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor)

Another well-known medicinal mushroom, turkey tails can be found year-round and we’ll often harvest them well into winter.

They have a distinctive striped pattern that reminds some people of turkey’s tails, which gives them their name. Turkey Tail Mushrooms are difficult to identify, though none of their lookalikes are particularly dangerous. The main issue is that you might not get the benefits of true turkey tails, so be extra careful when identifying Turkey Tail Mushrooms if you want to enjoy their benefits.

As a tough woody mushrooms, they’re best made into tea for medicinal use. Studies show that Turkey Tail Mushrooms are antioxidant and immune-boosting, and they’re used to:

- Improve immune response to common illnesses (like the common cold) and infection

- Improve cancer survival rates when used alongside traditional treatments

- Combat viral infections like HPV

- Improve digestion and promote a healthy microbiome.

Birch Polypore (Fomitopsis betulina)

As the name suggests, Birch Polypore is another medicinal mushroom that grows on birch. It generally grows on dead and dying birch, when the tree is completely dead (or close to it).

According to one peer-reviewed study,

“Modern research confirms the health-promoting benefits of F. betulina. Pharmacological studies have provided evidence supporting the antibacterial, anti-parasitic, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, neuroprotective, and immunomodulating activities of F. betulina preparations. Biologically active compounds such as triterpenoids have been isolated. The mushroom is also a reservoir of valuable enzymes and other substances…. In conclusion, F. betulina can be considered as a promising source for the development of new products for healthcare and other biotechnological uses.”

They’re relatively common anywhere birch trees are abundant.

Tinder Polypore (Fomes fomentarius)

Like Chaga and Birch Polypore, tinder polypore is another medicinal mushroom that grows on birch. The name comes from the fact that it was used historically as a tinder source to carry fire, though both chaga and birch polypore were used as tinder as well.

Their use as a traditional tinder source by survivalists causes some to miss their medicinal benefits. Mushroom expert Tradd Cotter sums it up nicely,

“[Tinder polypore mushrooms] are wonderfully rich in compounds similar to those of turkey tail (Trametes versicolor), including polysaccharide-K, a protein-bound polysaccharide commonly used in Chinese medicine for treating cancer patients during chemotherapy. Studies have found that these mushrooms can help boost and modulate immune system function, regulate blood pressure and sugar levels, lower cholesterol, and provide cardiovascular and digestive support. They contain antiviral and antibacterial properties as well as anti-inflammatory compounds, and they also have been shown to suppress many cancer cell lines.”

Tinder polypore are available year-round as a perennial mushroom.

Witches Butter (Dacrymyces palmatus)

One of the easiest mushrooms to spot in the winter landscape, Witches Butter Mushrooms are a type of bright orange jelly fungus. They’re squishy and honestly, they’re like a strange wrinkled brain growing right out of wood. They’re hard to miss!

Once the wood is infected, witches’ butter mushrooms will continue to sprout year-round anytime conditions are right (regardless of the temperature).

Historically, they often infected timbers and door frames in houses and people took them as a sign of a witches’ curse. They’d stab and burn them to try to break the curse…but unfortunately, they’d just keep coming back anytime the weather was cool and humid (which was often due to poorly ventilated cooking setups).

They’re an edible mushroom, though not particularly tasty…they more or less taste like nothing.

Witches butter is usually eaten as a medicinal mushroom, and studies in Asia show that it’s helpful for certain respiratory conditions.

Enoki (Flammulina velutipes)

Wild Enoki Mushrooms look a lot different than cultivated specimens, which are grown in special conditions to get them to have pure white, elongated stems. In nature, enoki mushrooms have amber-brown caps that look wet and sticky, and they sprout during cold weather.

It’s not uncommon to see enoki mushrooms growing out of logs in the snow. I usually see them in November and December here in Vermont, when temperatures are consistently below freezing and veggie gardens are a distant memory.

Since they’re a “little brown mushroom” it can be tricky to properly identify enoki in the wild, and you need to watch out for deadly galerina (among other deadly small brown mushrooms). The only way to positively ID these mushrooms is with a spore print, so be careful when foraging.

They’re not a beginner mushroom, but they can be fun to “forage with your eyes” even if you never cook them up in the kitchen.

Lion’s Mane (Hericium sp.)

These are the tastiest edible winter mushrooms, at least in my opinion. Some would argue that enoki or oysters are better, but that’s a matter of personal taste.

Lion’s mane mushrooms are easy to identify since nothing else has that toothed “mane” like appearance and a stark white mushroom. They’re a lot easier to find before snowfall obviously, and we usually find them in the cold (but not deep cold) months. Around November here in Vermont, but they can be found throughout the winter slightly further south.

They taste a bit like crab or lobster and can be used as a substitute for seafood in all manner of recipes. They’re also medicinal, and it’s currently being studied as a treatment for Alzheimer’s, dementia, and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Winter Oysters (Pleurotus sp.)

Certain species of oyster mushrooms will appear all winter long, even in the far north. Personally, I don’t like oyster mushrooms (though everyone else seems to), so I know very little about these species.

Sarah from Roots School pointed out a cluster of them growing on some downed trees during a cold season foraging walk, and I snapped a picture.

Here’s where you can find information on Identifying Oyster Mushrooms.

Artist’s conk (Ganoderma applanatum)

A reishi mushroom look-alike, this perennial mushroom is available year-round. While reishi are softer, and quickly eaten by slugs and insects, artists’ conk is woody and will hang on through the winter months. I’ll occasionally see these in woods that are rich with reishi, and they look more or less like a geriatric reishi sticking out of logs.

They’re in the same genus, and have some of the same medicinal properties.

Named artist’s conk because the bottoms hold marks when touched, and you can carve beautiful pictures into their pore surface.

Red-belted polypore (Fomitopsis pinicola)

Another tough perennial mushroom, this one’s similar to tinder polypore in appearance but it has a red belt at the bottom. Like other Fomitopsis species, it’s medicinal and used for tinder.

Though I see tinder polypore just about everywhere in the woods, I’ve yet to come across this one.

Amber jelly roll (Exidia recisa)

Similar in texture to Witches Butter Mushrooms, this little jelly fungus doesn’t mind the cold one bit. I’ve yet to find these, though they’re supposedly incredibly common.

Here’s a video guide on foraging Amber Jelly Roll:

Black Jelly Roll (Exidia glandulosa)

There are a few winter species of Exida mushrooms that are available in the winter months, and Exidia glandulosa, or “Black Jelly Roll” is also around.

Some people call that one witches butter, or black witches butter which leads to a lot of confusion.

Wood ear (Auricularia angiospermarum)

Another squishy brown winter mushroom, woods ear mushrooms are common in Asian cooking.

This video shows you the differences between Amber Jelly Roll and Woods ear:

Brick caps (Hypholoma sublateritium)

I’ve never found these, at least not to my knowledge. Like enoki, they fall into the category of “little brown mushrooms” that look a lot like deadly galerina, so they’re not for beginners.

This video takes you through what you need to know to forage Brick Caps, but make sure you’re 100% certain on your identification as mistaking this one can be deadly.

Warm Climate Winter Mushrooms

Those of you in warmer climates can find even more, especially the Pacific Northwest where winter rains cause huge flushes of cool-season mushrooms.

As I mentioned, you won’t find these in winter in the Northeast, but you will find them in other places right alongside the hardier winter mushrooms listed above. There are lots of articles on each of these, so I won’t cover them in detail here, as many dedicated foragers already know these quite well.

- Yellowfoot Chanterelle (Craterellus tubaeformis)

- Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus cornucopioides)

- Hedgehog Mushroom (Hydnum repandum)

- Candy Cap (Lactarius sp.)

Morel mushrooms are also considered a “cool season mushroom” but they don’t come out until early April in Oregon, and we don’t see them until late May here in Vermont. That range is their season more or less where ever you are in the US, so once you’re done with winter mushrooms they’re not far behind.

Mushroom Foraging Guides

Looking for more mushroom foraging guides?

I found a small source of chaga. When harvesting do you gouge out the orange chaga that is visable after the outward growth has been harvested. I left it when I harvested it as well as about 1/2 of the protruding section hoping it will grow.

Thanks Brian

This post about foraging for chaga will give you all of the information that you need. https://practicalselfreliance.com/foraging-and-using-chaga-mushroom/

Do you have a post on how to use them?

Most of the mushrooms listed have a link to a post that tells you how to use them. Just follow the link for that specific mushroom and it should take you to that post.