Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

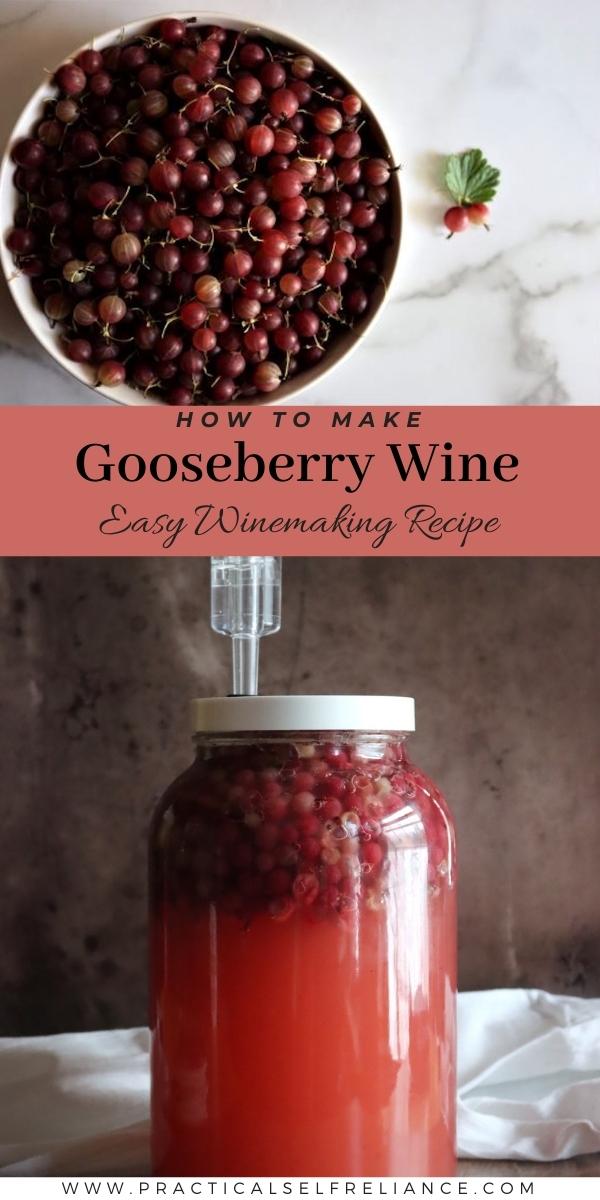

Gooseberry wine is the perfect way to enjoy these tart, short-season summer fruits. Add honey to turn this recipe into a rich gooseberry mead (or gooseberry melomel).

Gooseberries are one of those short-seasoned fruits, only found for a few brief weeks in late spring or early summer. They’re lovely in homemade gooseberry jam or gooseberry pie, but if you can gather enough during this time, a sensational wine awaits you.

Gooseberries come in many shades, but the ones most commonly used for winemaking are green. Green gooseberries will produce a white wine, while pink and red varieties will produce a blush wine.

Both are pleasant and well worth drinking.

These tart summer fruits have been made into wine as long as they’ve been grown, and there are plenty of historical recipes for gooseberry wine.

A recipe from an 1805 book called “The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy:”

“Gather your gooseberries in dry weather, when they are half ripe, pick them, and bruise a peck in a tub, with a mallet; then take a horse hair-cloth, and press them as much as possible, without breaking the seeds. When you have pressed out all the juice, to every gallon of gooseberries put three pounds of fine dry powder sugar, stir it all together till the sugar is dissolved, then put it in a vessel or cask which must be quite full. If ten or twelve gallons, let stand a fortnight; if a twenty-gallon cask, five weeks. Set it in a cool place, then draw it off the lees, clear the vessel of the lees, and pour in the clear liquor again. If it be a ten-gallon cask, let it stand three months; if a twenty-gallon four months, then bottle it off.”

Modern recipes are a bit different, and tend to use fully ripe fruit. Most of them also freeze the gooseberries before making wine to help break down their pectins, which results more clarity in the finished wine (and also helps extract their flavor once thawed).

In general, though, making gooseberry wine is straightforward and simple, following the same basic steps as any small-batch country wine.

You’ll use the fruit in the primary ferment, along with some sugar to balance out the tartness, a few additional winemaking additives, and a winemaking yeast.

This little mixture will ferment for a week or so, until the active fermentation begins to taper off. Then it is racked into a clean fermentation vessel with the help of a siphon, leaving the sediment and fruit behind. Here, it will ferment a bit more slowly until the wine has clarified.

Finally, the wine should mature by bottle-aging to ensure a well-rounded, balanced flavor.

These instructions have been written assuming you are already acquainted with familiar winemaking procedures and terminology. If new to winemaking, I highly suggest you read these guides to fill you in:

- Beginners Guide to Making Fruit Wines will take you through every step and stage of the winemaking process.

- How to Make Mead (Honey Wine) is nearly the same, but it provides an overview of the differences when working with honey instead of sugar.

- Equipment for Winemaking will tell you all about the equipment you’ll need to make your first batch of wine (besides your ingredients).

- Ingredients for Winemaking explains everything else you’ll need (besides yeast).

- Yeast for Winemaking is a world all of its own. There are dozens of common strains and hundreds of lesser-known ones. This will help educate you to pick the right one.

Ingredients for Gooseberry Wine

Only a few simple ingredients are necessary to make gooseberry wine.

For those who are fresh to small batch winemaking, you can read this quick guide on winemaking ingredients to help you understand why each of these ingredients is important.

To make a one-gallon batch (about 4 bottles) of gooseberry wine, you will need:

- 2-¼ lbs gooseberries (1 kg or 7-½ cups)

- 5-½ cups of sugar (or 3 lbs honey for mead)

- Water to fill

- 1 tsp Yeast Nutrient

- ¼ tsp Wine Tannin

- 1 tsp Pectic Enzyme

- White wine yeast

Gooseberries are a high-pectin fruit, so you will definitely need a pectic enzyme to help break their pectin content down. Gooseberries also contain a decent amount of tannins, so just a tiny bit of additional wine tannin will be needed.

Gooseberries are also quite acidic on their own, so you won’t need to add an acid blend or lemon juice.

You can purchase many of these common winemaking ingredients together in a kit for just a few dollars. All you’ll need in addition is a wine yeast and a packet of yeast nutrient.

For yeast, both white wine yeast and champagne yeast work well, but they’re generic and are used for just about any type of wine and don’t add much character. Some specific yeasts that work well with goosberries include CY17, Lalvin EC-1118, and Lalvin 71B-1122.

Lalvin 71B-1122 will metabolize the acid content of gooseberries well, and balance out their flavors. Champagne yeasts, like Lalvin EC-1118, will yield a dryer wine with a higher alcohol content.

Gervin GV9 is also a good yeast as well for gooseberry wine, although harder to find. This German-style wine yeast is great for fruits with higher malic acid levels like gooseberries and rhubarb, yielding nice white wines with a fruity fragrance.

Winemaking Equipment

Alongside these winemaking ingredients, some equipment will also be needed. This includes:

- One Gallon Glass Carboy (generally sold as a kit with a rubber stopper and water lock)

- Rubber Stopper and Water Lock (if not included above)

- Brewing Siphon

- Wine bottles or Flip-top Grolsch bottles

- Bottle Corker and some clean, new corks for bottling

- Brewing Sanitizer

When making fruit wines with the fruit included during primary fermentation, I prefer to use a wide-mouth one-gallon carboy. This is a better choice than the traditional narrow-neck vessel, which can easily get clogged with fruit pulp. The wide mouth also allows me to seal the wine with a water lock right from the start, which is particularly helpful in a home with curious kids or cats who love to explore open containers.

While you can begin fermentation in a large bowl or brewing bucket, since a water lock isn’t strictly necessary until secondary fermentation, I find the wide-mouth carboy method works best for me. It keeps everything clean and simplifies the process.

Making Gooseberry Wine

As previously mentioned, gooseberries are a high-pectin fruit. This is great for jam and jelly-making, but not so helpful for winemaking. To help break down the pectin content of your fruit, freeze gooseberries for one week before you plan to make your wine.

When ready, remove and thaw gooseberries. If desired, gooseberries can also be placed in a brewing bag for ease of removal later. Gently mash the berries with a potato masher and move to a wide-mouth carboy. Do note, be careful not to over-mash and crush the pips as this will release more pectin into your wine.

Cover with boiling water, and add the sugar, pectic enzyme, wine tannin and yeast nutrient. Stir until well dissolved. Once cool, add the yeast. Follow the instructions given on your particular yeast before adding.

Many yeasts need to be rehydrated first by being placed in a small amount of room temperature water before being added. Once your yeast is added, top with enough water to fill the container, leaving 2 inches of headspace.

Seal with a water lock. Soon you should see bubbling as the wine enters an active fermentation. Let the wine ferment in primary for 7 to 10 days, or until you see fermentation begin to slow.

Next, move the wine to a clean fermentation vessel for secondary ferment, leaving the fruit and sediment behind. Once you’ve siphoned your wine to a clean carboy, top it again with enough water to bring the liquid level up to the neck of the carboy (you want to expose as little of the wine to air as possible, while still leaving some headspace).

Seal with a water lock and let ferment until the wine clears (This can range from 6 weeks to 6 months). Many recipes recommend a minimum of 4 months in secondary for gooseberry wine and others up to 6 months.

Additional rackings may be needed to help clarify the wine.

Gooseberry Mead

If making mead, you should allow your wine an even longer secondary ferment, as honey is less digestible than sugar for your yeast. Gooseberry mead (or, technically, gooseberry melomel) should stay in secondary for at least 2 to 6 months.

Toward the finish of secondary, sample your wine to test the flavor. The taste should be balanced at this point, although the wine is not quite aged. If needed, adjust to your tastes.

If you decide to backsweeten, be sure to ferment for another week before bottling. Wine should also be stabilized before sweetening to halt further fermentation. Add 1 Campen tablet and ½ teaspoon potassium sorbate before sweetening to stabilize your wine.

Once bottled, let the wine bottle age for a year before drinking. Gooseberry wine really benefits when allowed to mature.

Ways to Preserve Gooseberries

Have more gooseberries than you know what to do with? There are many ways to preserve gooseberries!

Gooseberry Wine

Ingredients

- 2 1/4 lbs gooseberries, 7-½ cups

- 5-½ cups sugar

- Water

- 1 tsp yeast nutrient

- 1 tsp Pectic Enzyme

- ¼ tsp tannin powder

- wine yeast, see note

- Optional ~ Campden Tablet and Potassium Sorbate for Stabilizing, I do not use these

Instructions

- Freeze gooseberries for one week beforehand to help break down their pectin.

- When ready, thaw gooseberries and place in a wide-mouth carboy (a brewing bag can be used as well).

- Gently mash the berries. Cover with water and add the sugar, pectic enzyme, tannin, and yeast nutrient. Stir until dissolved.

- Add the wine yeast last. If needed, pitch the yeast by rehydrating it in a small amount of room-temperature water for 10 minutes before adding it to the wine.

- Top with more water so that 2 inches of headspace is left and seal the carboy with a waterlock.

- Allow to ferment for 7 to 10 days, until fermentation slows.

- Siphon to a clean carboy for secondary, leaving the fruit and sediment behind. Top with water to bring the level up to the neck of the carboy and seal with a waterlock.

- Ferment in secondary until clear. A secondary ferment of at least 4 months is recommended. (You may wish to ferment in secondary for 4 to 6 weeks and then rack to a clean container to ferment for another 2 months to clear sediment.)

- If needed, rack the wine again to help clear the sediment and ferment until clear.

- Once clear, sample your wine. For backsweetening, see notes below.

- When ready for bottling, siphon to clean bottles, and bottle with wine corks.

- Bottle age for a year for the best quality wine.

Notes

Yeast

For gooseberry wine your best yeast choices are champagne and white wine yeast. Some particularly good strains for gooseberry wine include CY17, Lalvin EC-1118, and Lalvin 71B-1122. See notes within the article for the particular qualities of each yeast.Stabilizing and Back Sweetening

If the wine is too dry for your tastes once secondary is complete, backsweetening can be done. First, rack to a clean container to avoid stirring up sediment and stabilize the wine by adding 1 Campden tablet and ½ teaspoon of potassium sorbate. This will help kill the yeast so that fermentation does not start back up again. (Skipping this step can cause bottled wine to burst under pressure.) Once stabilized, you can add sugar and adjust the wine to your taste. This is most easily done by making a simple syrup from equal parts water and sugar in a heated saucepan. Start with ½ cup water and ½ cup sugar for a one-gallon batch of gooseberry wine. Once sweetened, place back into ferment for at least a week.Winemaking Recipes

Why stop with gooseberries? There are so many delicious country wines to fill your cellar…

I was so happy with this recipe! The gooseberries gave the wine an amazing color and flavor, and it was just sweet enough to be balanced.

I was hoping that’s what you’d say! Thanks; gooseberry wine it’ll be!

You’re very welcome.

I have about 15 gooseberry plants here and know that I will be inundated with them in a year or two. Some wine sounds like a really good solution! I couldn’t tell from the picture, but do you bother to “tip and tail” them or do you just freeze them with the stem and end spiky thing? It would be a real time-saver if I didn’t have to do that! Thanks, Barb

So this recipe, and my recipe for gooseberry jelly (https://creativecanning.com/gooseberry-jelly/) does not require removing the tips and tails. Yes, it’s a huge time saver. I’ll do a batch or two of jam, maybe a pie or two, but then I’m tired of spending all that time trimming and the rest go into jelly and wine. Enjoy!