Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

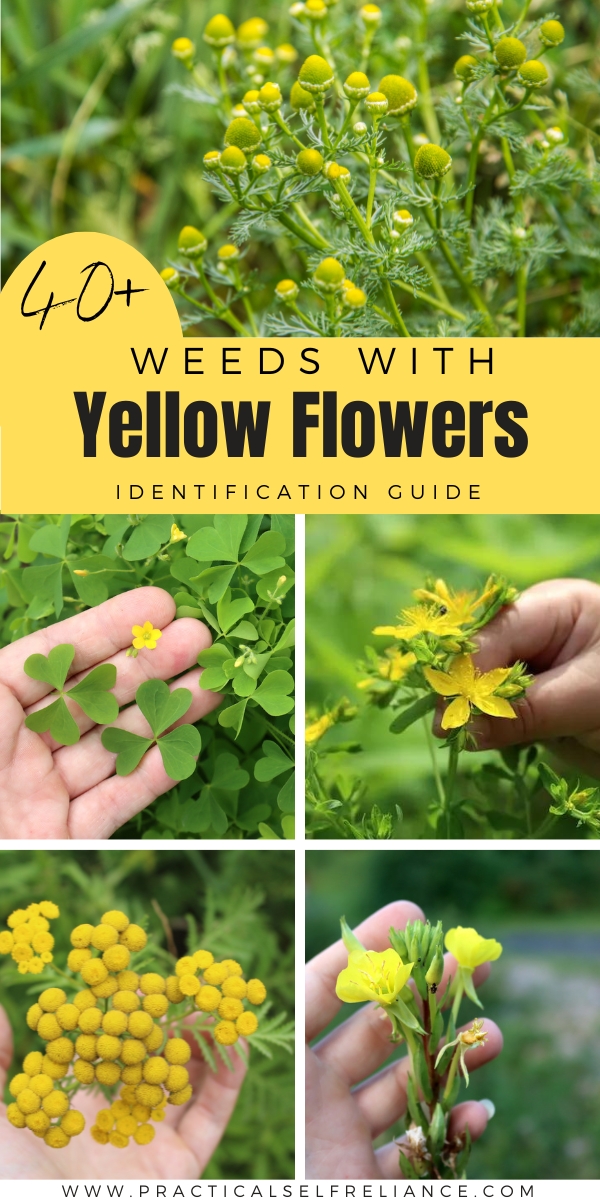

Weeds with yellow flowers are some of the most common in nature, and the list goes well beyond simple dandelions. Bees love yellow flowers, and these vigorous weeds know how to please. Maybe they’re not the most popular with people, but yellow flowered weeds don’t mind…and they’ll grow up through sidewalk cracks and highway medians without a care in the world.

Not sure which one you have? This identification guide will help you figure it out!

Table of Contents

- WEEDS WITH YELLOW FLOWERS

- Birds Foot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus)

- Key identification features

- Black Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta)

- Key identification features

- Black Medic (Medicago lupulina)

- Key identification features

- Butterweed (Packera glabella)

- Key identification features

- Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara)

- Key identification features

- Comfrey (Symphytum grandiflorum)

- Key identification features

- Common Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

- Key identification features

- Common Lantana (Lantana camara)

- Key identification features

- Creeping Buttercup (Ranunculus repens)

- Key identification features

- Cypress Spurge (Euphorbia cyparissias)

- Key identification features

- Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

- Key identification features

- Dyer’s Woad (Isatis tinctoria)

- Key identification features

- Elecampane (Inula helenium)

- Key identification features

- Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis)

- Key identification features

- Golden Clover (Trifolium aureum)

- Key identification features

- Grass-leaved Goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- Key identification features

- Great Mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

- Key identification features

- Groundsel (Senecio vulgaris)

- Key identification features

- Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

- Key identification features

- Loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris)

- Key identification features

- Meadow Hawkweed (Hieracium caespitosum or Pilosella caespitosa)

- Key identification features

- Mock Strawberries (Potentilla indica)

- Key identification features

- Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

- Key identification features

- Puncturevine (Tribulus terrestris)

- Key identification features

- Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

- Key identification features

- Ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris or Senecio jacobaea)

- Key identification features

- Rush Skeletonweed (Chondrilla juncea)

- Key identification features

- Sow Thistle (Sonchus sp.)

- Key identification features

- St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

- Key identification features

- Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

- Key identification features

- Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

- Key identification features

- Wild Radish (Raphanus raphanistrum)

- Key identification features

- Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

- Key identification features

- Wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris)

- Key identification features

- Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.)

- Key identification features

- Yellowcress (Rorippa spp.)

- Key identification features

- Yellow Bedstraw (Galium verum)

- Key identification features

- Yellow Goatsbeard (Tragopogon spp.)

- Key identification features

- Yellow Nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus)

- Key identification features

- Yellow Toadflax (Linaria vulgaris)

- Key identification features

- Wild Weed Identification Guides

This article is written by Morgan Hyde, a former reference librarian from Arizona. Working for the library refined her passion for learning and deep research—a passion that began in her rural AZ upbringing and continues in her work as a writer and editor. If it’s something she can do on her own, it’s something wants know about.

Yellow flowers are incredibly common with wild weeds, and there’s a good chance you have half a dozen of these growing in your lawn, garden beds or along your sidewalk. Most of them clump together and spread en masse. You’ll find them growing in groups, clumps, stands, and mats! Possessing the most popular color with bees and other pollinators, yellow-flowered plants generally grow taller with tall, erect stems. After all, if there are others using their trump card, they need a way to be spotted amongst the crowd.

Many plants here will provide you with a tasty snack or a pretty dye, and several of them you might want to keep on hand for their medicinal qualities.

A few plants on this list are considered mildly to severely toxic but not considered outright poisonous. It can be confusing with some plants here. Tansy, for example, has a long history of being used medicinally– and likely can still be used for this purpose– but there is an oil in it that can become deadly in too high quantities. With any herbal medicines, take the time to research the plant based on your personal needs and consult a doctor if you’re not sure.

WEEDS WITH YELLOW FLOWERS

Below, you’ll find a list of the most common weeds that produce yellow flowers. Most aren’t native to North America, and almost every single one is considered invasive. However, some are just considered annoying because they appear on lawns and gardens unexpectedly. Regardless of whether it’s invasive or not, each plant here has something to offer.

Yellow flowers are tall! Many of the plants on this list can reach 6 feet or more in height, and you’ll have to look up to find them. But just because some of them are showy doesn’t mean you shouldn’t keep an eye out around your toes whenever you walk through sunny areas.

Here’s the list of weeds with yellow flowers that I’ll cover:

- Birds Foot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus)

- Black Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta)

- Black Medic (Medicago lupulina)

- Butterweed (Packera glabella)

- Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara)

- Comfrey (Symphytum grandiflorum)

- Common Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

- Common Lantana (Lantana camara)

- Creeping Buttercup (Ranunculus repens)

- Cypress Spurge (Euphorbia cyparissias)

- Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

- Dyer’s Woad (Isatis tinctoria)

- Elecampane (Inula helenium)

- Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis)

- Golden Clover (Trifolium aureum)

- Grass-leaved Goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- Great Mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

- Groundsel (Senecio vulgaris)

- Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

- Loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris)

- Meadow Hawkweed (Hieracium caespitosum or Pilosella caespitosa)

- Mock Strawberries (Potentilla indica)

- Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

- Puncturevine (Tribulus terrestris)

- Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

- Ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris or Senecio jacobaea)

- Rush Skeletonweed (Chondrilla juncea)

- Sow Thistle (Sonchus sp.)

- St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

- Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

- Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

- Wild Radish (Raphanus raphanistrum)

- Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

- Wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris)

- Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.)

- Yellowcress (Rorippa spp.)

- Yellow Bedstraw (Galium verum)

- Yellow Goatsbeard (Tragopogon spp.)

- Yellow Nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus)

- Yellow Toadflax (Linaria vulgaris)

Now I’ll take you through how to identify each one.

Birds Foot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus)

You won’t see Birds Foot Trefoil waving in the wind—it prefers to grow lower to the ground, no higher than any of its grassy neighbors. Blooming from June to September, you’ll spot its little yellow flowers anywhere with plenty of rain and sandy soil. Highly invasive, Birds Foot Trefoil can’t be controlled by fire and must be pulled out by the roots. Fortunately, though, it can be a useful plant to have around.

Birds Foot Trefoil is best known for preventing soil erosion and was originally planted in North America for this purpose. Pressing the fresh plant against your skin is a great way to treat a wide range of skin irritations, from bug bites to scratches. Dried Birds Foot Trefoil has a variety of medicinal properties, but in excess can cause respiratory failure and generally shouldn’t be consumed.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Pea-like

- 1.5in long

- Clusters of 2-12

- Occasionally tinged with red

Seeds:

- 1in long pods

- Brown-black

- Pods grow in clusters similar to a bird’s foot

Leaves:

- Clover-like

- 1.5in long

- 5 leaflets arranged on a stem

- Groups of 3 leaflets on a short stalk

- 2 stalkless leaflets at the base of the stem

Here’s how to identify Birds Foot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus)

Black Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta)

One of the most recognizable plants on North American wildflower lists, Black Eyed Susans are a beloved staple in many gardens. Featuring an “eye” made up of hundreds of tiny flowers and a wide, inviting landing pad, Black Eyed Susans are a treat for any pollinator. An aggressive grower, Susans aren’t technically considered invasive, but they’re annoying enough to be considered a weed.

But you might want to let Black Eyed Susans grow as fast as they want—they have an array of medicinal uses. The roots of Black Eyed Susans can be used for similar purposes as Echinacea in treating colds by stimulating immune systems and fighting respiratory irritations.

Key identification features

Black Eyed Susans and Brown Eyed Susans look very similar, which isn’t surprising considering they come from the same genus. However, Brown Eyed Susans aren’t as aggressive, bloom much later in the year, and have smaller flowers.

Flowers:

- Radial

- 7-20 petals

- Dark brown/purplish center dome

Leaves:

- Ovate to lanceolate

- Lower leave taper into a stalk

- Serrated

- Rough to the touch

General:

- Grooved, hairy stems

Here’s how to identify Black Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta)

Black Medic (Medicago lupulina)

Generally considered a nuisance in lawns and gardens, Black Medic is a non-native plant that easily makes itself at home. While the seeds are edible, most people prefer to pull up this plant before it matures—seeds from the Black Medic can persist in soil for years on end. Fortunately, the leaves are edible as a potherb, so your efforts to control this plant won’t go to waste!

In recent years, Black Medic has been shown to have powerful antibacterial properties when in the form of aqueous extracts (a laboratory extraction involving drying, blending, and submitting the leaves to centrifuge).

Key identification features

Black Medic looks similar to many plants in the Trifolium genus, including Golden Clover (Trifolium aureum) which is listed below. The main difference is that Black Medic grows its stems along the ground while the Clovers have erect stems.

Flowers:

- Tiny, rounded clusters

- 10-50 flowers per cluster

Seeds:

- Kidney-shaped fruits

- Grown in clusters

- Turn black when ripe

- Leaves:

- Trifoliate

- Clover-like

- Groups of 3 oval leaflets

- The center leaflets protrude slightly out

General:

- Trailing, hairy stems

Here’s how to identify Black Medic (Medicago lupulina)

Butterweed (Packera glabella)

You won’t have any problem spotting Butterweed—you’ll have problems spotting anything else mixed in with it! Growing in colonies that can span whole acres of prairie land, Butterweed produces unbroken fields of bright yellow flowers from April to June. While it’s an excellent plant for pollinators, you may want to be careful about adding it to your garden (unless you want it taken over).

Butterweed is one of seven Missouri ragworts and every one of them is toxic. Despite this, it has a long history of medicinal uses: Native Americans used it to treat irregular menstruation and to reduce complications from childbirth, and some sources claim it has been used to treat rheumatism.

Key identification features

From a distance, it can be hard to tell the difference between Butterweed and Wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris). Both create dense carpets of yellow flowers in the spring. But up close you’ll see that Wintercress has dozens of branching stems coming up from its base. See below for a deeper description of Wintercress.

Flowers:

- Clusters of disc flowers

- Up to 15 ray florets

- Several flowers grow in clumps at the tops of stems

Seeds:

- Looks like a small dandelion head

Leaves:

- No basal leaves during flowering

- Toothed margins

- Rounded, almost fan-shaped

General:

- Single, unbranched stalk

- Grows in colonies

- Heavily ridged stems

- Hollow stems

Here’s how to identify Butterweed (Packera glabella)

Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara)

Also called “The Son Before the Father,” coltsfoot blossoms very early in the spring, before the plant has even developed leaves. You’ll see the spindly yellow flowers sticking right out of the soil alongside the road (and other waste places).

Historically, coltsfoot was used as a cough remedy, and it still is by some herbalists, but with caution. There is some evidence that coltsfoot may be linked to liver damage, especially with extended use.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Yellow, almost dandelion-like flowers

- Scaly, bract like leaves on the flower stem

Leaves:

- Large flat leaves in the rough shape of a hoof

Comfrey (Symphytum grandiflorum)

While comfrey often has pink to purple flowers, it also is a yellow-flowered weed on occasion.

Comfrey has long been grown as an ornamental plant in Europe and the US—it makes an excellent groundcover and provides lovely flowers in the spring. However, as a non-native plant and an aggressive grower from its deep roots, Comfrey has come to be seen as invasive in recent years.

One of the best uses for Comfrey in your garden is actually as a fertilizer! Comfrey draws up and stores nutrients from the soil that can be easily released into your compost. If you’re running out of space in your compost bin, consider brewing it as a tea and drizzling it over what’s already present.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Yellowish-white

- Bell to tubular shaped

- 1-3in long

- Red flushed buds

- Blooms in drooping clusters

Leaves:

- Fragrant

- Hairy and rough

- Elliptical to ovate

- 2-6in long

Here’s how to identify Comfrey (Symphytum grandiflorum)

Common Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

Growing Common Goldenrod in your garden is a labor of love; the rhizomatous roots cause it to spread where it will and removing it isn’t easy. However, out on the prairies it never grows aggressively enough to drive out other plants. As such, it might be a “weed” but it isn’t a native invasive. Why might you want it in the garden if it can be a problem, you ask? Common Goldenrod has a wealth of medicinal uses.

The young leaves and flowering stems are edible when cooked and are commonly used to make tea, tea that has historically been used to treat diarrhea, fevers, and even snakebites! When the flowers are chewed, the juice can be used to treat sore throats. Poultices from the roots are good for burns—and those are just a few uses!

Key identification features

Does it look similar to another plant? Common Goldenrod may be confused for either Ragwort (Packera obovate or Senecio obovatus), or Ragweed (Ambrosia spp.). While Ragwort doesn’t look similar on close inspection, it is highly toxic, so be extra careful: look for larger, daisy-like flowers, and if it’s blooming in the Spring. If the answer is yes to these, you’re looking at Ragwort. Ragweed, on the other hand, has the same overall shape as Common Goldenrod, but has small, inconspicuous flowers. Also take a look at the leaves: if the leaves look at all complicated, then it’s Ragweed.

Flowers:

- Cup-shaped flowers

- 7-20 petals

- Conical-shaped clusters

- 100 to 1300 flowers per cluster (or more)

- Fall flowers (August to October)

Leaves:

- Simple and lanceolate

- Serrated edges

- Hairy underneath but smooth to the touch

General:

- Erect to arching stems

Here’s how to identify Common Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

Common Lantana (Lantana camara)

Many of us know Common Lantanas to be a nice ornamental plant to have around our homes. But for those living in the tropical portions of the nation, it’s an invasive pest! Even the more arid regions should be cautious of letting this plant grow wild—the Common Lantana has been shown to increase the risk of wildfires spreading up to the canopy of nearby trees.

Studies are mixed on the medicinal uses of Common Lantana: many tout it as having beneficial properties while also stating its leaves and berries are toxic. At least one study looked at poison control cases and found children who consumed the berries showed minimal to no symptoms. If you choose to try eating them, exercise caution and make sure everything you try is fully ripe.

Outside of consuming them, Common Lantanas are a beautiful plant with wonderfully aromatic leaves. If you’re particularly crafty, you can look into using the stalks from Lantanas to make furniture like chairs or tables!

Key identification features

Common Lantana and Verbena (Verbena spp.) have similar, multi-colored flower clusters and are used as ornamental groundcovers. To tell the difference, look for any hint of yellow (Verbena tends to be white/pink/purple/blue) and consider the time of year—Lantanas can bloom year-round while Verbena only blooms in the summer and fall.

Flowers:

- Star-shaped

- Tubular

- Multi-colored clusters with yellow at the center

Seeds:

- Berries form in drupes (clusters)

- Green when unripe

- Blue/black when ripe

Leaves:

- Simple

- Ovate

- Serrated edges

Here’s how to identify Common Lantana (Lantana camara)

Creeping Buttercup (Ranunculus repens)

If you have grazing animals in your yard, chances are you’ll start to see Creeping Buttercup popping up in their favorite areas. Containing a bitter oil, most grazing animals avoid Creeping Buttercup, allowing it to pop up in place of the plants they chew down. While you may have heard it’s toxic to cattle (which it is), it’s the oil that contains the toxin—dried Buttercups mixed in with hay won’t cause harm.

A native to Europe and Asia, Creeping Buttercup has become a bit of a nuisance in the US. Originally prized for its ornamental value, it has since broken out in the wilderness as an invasive plant. If you’re looking for something to help stabilize a pond border, this plant can help, provided you’re willing to keep it in check.

The leaves and roots of Common Buttercups are edible if the oil is first cooked out of them. However, they’re generally seen as too bitter to be palatable even then. Consider instead using it in poultices to treat sores or muscle aches and avoid the taste entirely!

Key identification features

Flowers:

- 5-7 petals

- Glossy, wedge-shaped petals

- 5 green floral leave right below the petals

- Loose cup shape

Leaves:

- 3-parted segments, deeply lobed and toothed

- Dark green

- Occasional pale spots

- Heart-shaped

General:

- Horizontal non-flowering stems

- Upright flowering stems

Here’s how to identify Creeping Buttercup (Ranunculus repens)

Cypress Spurge (Euphorbia cyparissias)

A compact plant with unusual flowers, Cypress Spurge is a treat to look at. If you’re planting it (or removing it in areas it’s become invasive) be sure to wear gloves. The stems and leaves extrude a white sap when broken that can cause irritation, swelling, or even blisters!

While some people use Cypress Spurge to treat toothaches, warts, or even constipation, there aren’t any studies showing if the treatments are effective, and it’s generally advised to avoid eating or using it in poultices.

Key identification features

Because they belong to the same genus, it’s easy to confuse Cypress Spurge (Euphorbia cyparissias) and Asthma-plant (Euphorbia hirta). The plants themselves look very different, but Asthma-plant has a wealth of medicinal uses where Cypress Spurge does not—if buying online, be careful not to confuse these two.

Flowers:

- Open cup shape

- Two bracts instead of petals

- Begins yellow and ages to red

Leaves:

- Oblong

- Soft

- Bottlebrush arrangement

General:

- Milky sap in leaves and stems

Here’s how to identify Cypress Spurge (Euphorbia cyparissias)

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

I’ve always believed Dandelions were considered weeds due to how quickly they spread. Much to my surprise, it’s also because they aren’t native to the US at all! Brought over to the Americas (and the rest of the globe) by Europeans for medicinal purposes, Dandelions have become so naturalized they aren’t considered a threat in their new ecosystems.

While Dandelions may have been used historically as medicine, in recent days they have seen a renaissance in its kitchen applications. The flowers, leaves, and roots are all edible, getting more bitter as they mature. Young flower heads taste like honey and can be made into fritters, eaten raw, or even added to batters! You can use the roots to make a coffee substitute by roasting and brewing them, or go the classic route and add the leaves to a fresh salad.

Key identification features

There are several plants that look similar to Dandelions in the flower or seed stage, enough that it would take several paragraphs to list them here. In general, you can tell it’s a Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) by looking for exactly one stem per basal rosette, and checking that the lobes/teeth on the leaves point back toward the stem.

Flowers:

- Radial

- Over 20 petals

- Toothed tips

- Single flowers per stem

- Close in the evening

Seeds:

- Downy seed heads

- Easily broken up by wind

Leaves:

- Deeply toothed

- Lobes are aimed back toward the stem

- Form a basal rosette

Here’s how to identify Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Dyer’s Woad (Isatis tinctoria)

Before sea routes between Europe and India were discovered, Dyer’s Woad was the plant to have on hand for creating blue pigments. Containing the same dying elements as true Indigo (though in lower concentrations), you can extract blue dye from the seeds or leaves of Dyer’s Woad. After the blue pigment has been extracted, you can even boil the used leaves to make a pink dye—two colors for one!

Unfortunately, Dyer’s Woad has become a highly invasive plant in the western US. Some states have even launched eradication attempts directed specifically at it and nothing else. So if you see it when out for a walk, feel free to collect as much as you want—just be sure to pull the whole plant out by the roots while you’re at it.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Flowers form a flat top on stalk ends

- 4 yellow petals and sepals

- Each 4 create an “X” shape

Seeds:

- Pods with a single seed

- Pods are light green when fresh

- Pods are dark brown when mature

Leaves:

- Lance-shaped

- Straight, white, midvein

General:

- Stems may be purple when in flower

Here’s how to identify Dyer’s woad (Isatis tinctoria)

Elecampane (Inula helenium)

A popular plant across history for medicinal and flavorful purposes, Elecampane is a useful addition to gardens to have on hand. In medieval times, the roots were candied and eaten as confections. It was even added to oils and wines—sometimes for flavoring, sometimes to treat snake and insect bites.

Today, many of these uses still hold their value: you can use it to give soap a violet scent, flavor food, infuse wine. It even contains chemicals that might reduce inflammation and kill bacteria, though there’s little research done into how effective it is in treating any condition. However, keep in mind that Elecampane is a non-native invasive plant in the US. Use caution if adding it to your garden as it is difficult to get rid of.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Over 20 string-like petals

- 3-6in wide

- Upright petals

Leaves:

- Lanceolate

- Over 6in long

- Wooly underside

- Netted veins

General:

- Densley wooly stems

Here’s how to identify Elecampane (Inula helenium)

Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis)

One of the few plants that only opens its flowers in the dark, Evening Primrose is an excellent choice to add to your moon garden. Late-night pollinators will find it a treat, and (if you want a natural way to attract birds to your yard) you’ll find they love this plant when it’s in seed. It can spread rapidly (and is considered weedy for this reason), but is easily controlled by careful handling.

The leaves, flowers, stalks, seeds, and the taproot are all edible, though you’ll want to know what stage your Evening Primrose is at in its biennial cycle before eating anything—some parts of the plant become too tough as they age or only appear in the second year. Additionally, the seed oil is a popular folk remedy for a wide variety of ailments and some studies are beginning to solidify its place in the herbal remedy lineup.

Key identification features

At a distance, Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) can look similar to Common Mullein (Verbascum sp.) due to both having tall spikes with tiny yellow flowers. But once you get closer you’ll be able to tell the difference.

Flowers:

- Cross-shaped

- 4-5 petals

- Bowl-shaped petals

- Close during the heat of the day

- Mild lemon scent

Leaves:

- Basal rosette

- Lanceolate shaped

- Wavy toothed, but shallowly

General:

- Reddish-green stems

Here’s how to identify Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis)

Golden Clover (Trifolium aureum)

Much less common than its white flowering neighboring species (Trifolium repens), Golden Clover has still managed to naturalize itself in the US. Rumored to have been ordered by George Washington from Europe, it wasn’t confirmed to be growing in North America until the early 1800s. As Golden Clover has a tendency to form colonies, it has become a known invasive in recent years, pushing out neighboring plants.

Not many uses for Golden Clover can be found—at least one species of bee enjoys the nectar from its bright yellow flowers. In foraging circles it’s seen as a “last resort” plant, being non-toxic but not particularly good to eat.

Key identification features

Golden Clover can look similar to Black Medic (Medicago lupulina), see above for a description of differences.

Flowers:

- Round

- About 20 petals

- Become brown and paper-like when aged

Seeds:

- Forms a pod with 2 seeds

Leaves:

- 3 sessile leaflets (clovers)

- Ovate, narrow

- Connected to main branch by a short stem

Here’s how to identify Golden Clover (Trifolium aureum)

Grass-leaved Goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

You might be delighted to come across a cheery spread of blooming Grass-leaved Goldenrod when out on a fall hike, but don’t be fooled—you might not want this native plant in your garden. While it is weedy in the way it grows, it also puts out a chemical to prevent neighboring plants from growing around it. If removing it from near your cultivated plants, focus on the leaves and roots to fully remove its toxic elements.

The same chemical that prevents nearby seeds from germinating, also produces a delightful scent when you crush the leaves of this Goldenrod. Additionally, it is a phenomenal pollinator supporter and is guaranteed to attract butterflies to it as the growing season comes to a close.

Key identification features

You may confuse Grass-leaved Goldenrod for Riddell’s Goldenrod (Solidago riddellii). Both have yellow flowers with grass-shaped leaves. However, the leaves on Riddell’s Goldenrod are folded over, wrapping around its stems where the Grass-leaved variety lies flat.

Flowers:

- Flat-topped flower heads

- Arrays of flower heads can span 1st across

- 7-35 ray florets surrounding 3-13 disc florets

Leaves:

- Grass-like

- Narrow, long, simple

Here’s how to identify Grass-leaved Goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

Great Mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

A non-traditional weedy plant, Mullein isn’t considered invasive in any areas with established plants. As it’s a biennial and dies off every 2 years after flowering, native plants in the area are often able to push it out before new seedlings can take root. However, in regions where plants are sparse (like areas affected by wildfires) it can push out native plants instead.

Records show this plant was used medicinally as far back as 2000 years ago—originally the leaves were smoked as a way to treat a variety of lung ailments. Additionally, poultices from the roots have been used by the Zuni tribe for centuries to treat skin infections, sores, and even athlete’s foot. Many other treatments have been made over the years by extracting oils from the stems and leaves.

Most treatments using Mullein don’t involve it being consumed as the hairs on the stems and leaves are irritating to the throat. Fragrant (and sometimes bitter) teas made from the leaves and flowers can be made, but ought to be thoroughly strained to remove the hairs.

Key identification features

When young, Great Mullein can look similar to Lamb’s Ear (Stachys byzantina)—check for whether the leaves are growing in a clump or the Mullein’s rosette. You may also confuse it with Common Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) by sight, but by touch the Common Evening Primrose won’t have the same fuzzy feel to it that Great Mullein has.

Flowers:

- Grow in cylindrical spikes

- 5 lobes

- Fragrant

Leaves:

- Soft, velvety

- Elliptical

- Large, over 6in long and 3-6in wide

General:

- 6-10ft tall

Here’s how to identify Great Mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

Groundsel (Senecio vulgaris)

A favorite plant for the young of some moths and butterflies, during larvae season you might not see many whole leaves on your local Groundsel. Native to Europe and Asia, Groundsel grows wild in the US but isn’t aggressive enough to be considered invasive. Keep an eye out if pulling it from your yard, though—the flowers can still sprout seeds after being weeded.

Groundsel does have edible leaves and has a varied history of medicinal uses as a diuretic, purgative, and a treatment for menstrual pains. Be cautious of consuming Groundsel regularly—chronic consumption can cause liver failure. It also isn’t recommended for consumption if you’re pregnant.

Key identification features

While the seed heads of both Groundsel and Dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) are very similar, it’s easy to tell the two plants apart. See above for how to identify if the plant is a true Dandelion.

Flowers:

- Look like dandelion buds

- No petals

- Disc-shaped flower heads

Seeds:

- Dandelion-like seed heads

Leaves:

- Lanceolate

- Rough to touch

- Deeply lobed

- Irregular teeth

General:

- Green and purple stems

- Hollow stems

Here’s how to identify Groundsel (Senecio vulgaris)

Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

A versatile and lovely plant, Lesser Celandine doesn’t appear for long during the spring season. One of the earliest plants to sprout under the increasing light, the large mats it makes can inhibit the growth of other native plants in the area. Non-native and considered invasive, feel free to pull up any Lesser Celandine you see to take home—just make sure to take up the tuberous roots while you’re at it.

The young leaves are edible raw or as a potherb. You can even use the young flower buds as an occasional substitute for capers! Be careful though—all parts of the plant are mildly toxic and only the youngest leaves can be eaten raw. The toxins are easily destroyed by heat or drying, so if you plan on consuming Lesser Celandine, consider cooking it well and eating small quantities.

Historically Lesser Celandine has been used to treat hemorrhoids, ulcers, and to clean teeth! Today it is generally advised against as an internal medicine due to the known toxins. Ointments made from it can be safely used externally for a variety of skin complaints.

Key identification features

Lesser Celandine can be confused for the native Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris L.). Check for the width of the petals on flowers: March Marigold has 5 wide sepals (that act as petals) as opposed to the numerous narrow petals of Lesser Celandine. If you pull up the plant and discover no tubers, you’re looking at Marsh Marigold.

Flowers:

- Grow on leafless stalks

- Daisy-shaped

- 6-12 narrow petals

Leaves:

- Dark green

- Wide kidney-shape

- Smooth with wavy edges

- U-shaped leaf stalks

- Dense basal rosette

General:

- Low growing

- Will form large mats

- Tuberous roots

Here’s how to identify Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

Loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris)

Considered a highly invasive non-native plant, many states have launched aggressive campaigns to restrict the growth of Loosestrife in wetland areas. You’ll easily be able to spot it in sunny or shady areas—Loosestrife commonly grows to be 6ft tall or more! With lovely clusters of bright yellow flowers, it doesn’t do a good job of hiding.

A variety of medical capabilities are attached to this plant, though very few studies have been done to show how effective Loosestrife might be in treating anything. Many people eat it to increase their vitamin-c intake, combat diarrhea, and inhibit nosebleeds. You can make a poultice out of Loosestrife to cleanse wounds and slow bleeding.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Primrose-like

- 5 petals and sepals

- Reddish-brown edges to petals

- Grow at the top of the plant in upper leaf axils

Leaves:

- Soft and hairy

- Lance-shaped

- 3-6in long

- Black and orange glands

General:

- Soft, hairy stems

- Grows up to 6ft in full sun, higher in shade

Here’s how to identify Loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris)

Meadow Hawkweed (Hieracium caespitosum or Pilosella caespitosa)

Meadow Hawkweed is theorized to have been brought over from Europe as an ornamental plant. It’s a non-toxic, nutritious plant, though how palatable it is may be up for debate. Feel free to collect it as a forage plant: it’s considered an invasive in many parts of the US and eating it is one way to control it! Be wary of letting it set in your garden as some studies show it may inhibit the growth of nearby plants.

Historically used in England to treat ailments ranging from cramps to lung disorders. Additionally, it was used in beauty treatments, though those seem to have been out of style long enough to make written records hard to track down.

Key identification features

The flowers of Common Catsear (Hypochoeris radicata) look similar to Meadow Hawkweed. You can tell the difference by looking for lobes on the leaves—Meadow Hawkweed has no lobing.

Flowers:

- Dandelion shaped

- 10-30 flower stems per plant

- 5-30 flowers per flower stem

- Flat-topped flower clusters

Seeds:

- Small achenes

- Bristly tufts at one end of every seed

Leaves:

- Basal rosette of leaves

- Smooth edges

General:

- Milky sap

- Very hairy stems and leaves

Here’s how to identify Meadow Hawkweed (Hieracium caespitosum)

Mock Strawberries (Potentilla indica)

Mock Strawberries and their less common sister Creeping Cinquefoil (Potentilla reptans) are both considered invasive non-native plants in the US. But perhaps the Mock Strawberries’ biggest offense is in the shape of its fruit—anyone who has taken a bite of a Mock Strawberry will instantly know they’ve been cheated out of the real thing. While not an offensive taste, the juicy and sweet taste you’re expecting is completely absent.

In addition to the fruits, the leaves of Mock Strawberries are also edible and can be added to salads or teas. Crushing the leaves turns them into an on-the-go poultice that can be applied to boils, burns, insect bites and more injuries.

Key identification features

Mock Strawberries (Potentilla Indica) look highly similar to the Wild Strawberry (Fragaria vesca) as they both grow low to the ground and spread through runners. Their fruits and flowers are also similarly shaped. When in the wild, you can look for two key differences: Wild Strawberries have white flowers, not yellow, and their fruits will droop down toward the ground. If it’s an easy to spot fruit, you may be looking at the upright Mock Strawberry.

Flowers:

- Star-shaped

- 4-5 petals

- Framed by 5 green sepals

Seeds:

- Red/burgundy fruit

- Strawberry-like to spherically shaped

- Covered in small red seeds

Leaves:

- Ovate

- Crenated

- 3-lobed

Here’s how to identify Mock Strawberries (Potentilla indica)

Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

Pineapple Weed gets its name not from the way pineapples look, but by the way it smells. When crushed or damaged, the leaves and flowers of this plant smell very similar to pineapple. Native to the Northwestern US, it isn’t considered invasive in the rest of the continent, but because it happily spreads outside of its native zone through disturbed areas and meadows, it’s generally considered a weed.

Going by the name Wild Chamomile in some areas, you can use this plant similarly to regular Chamomile—pluck the flower heads and steep them for teas or sauces. The greens are also edible and are an excellent addition to salads and other recipes. The tea is reported to be good for anxiety, stomach aches, and colds among other things. A wash made out of the plant can be used to treat irritated skin.

Key identification features

Pineapple Weed can look similar to Black Medic (see above) and Mayweed (Anthemis cotula). Check for a combination of fern-like leaves and greener flowers with no white in them to make sure you’re looking at Pineapple Weed.

Flowers:

- Globe or cone-shaped head

- Yellow-green colored

- Look like fuzz on the edges of the flower head

- Smell like pineapple with damaged

Leaves:

- Feathery or fern-like

- Finely dissected

- Smell like pineapple when crushed

Here’s how to identify Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

Puncturevine (Tribulus terrestris)

Puncturevine comes with a varied and odd collection of uses. Considered a “famine food” it hasn’t historically been any forager’s first choice. But as it grows aggressively (read, “invasively” in much of the US) it is often in plentiful supply. The leaves and shoots are edible when cooked. And the closed seed pods can be ground up into a flour for breads.

Medical analysis shows that Puncturevine contains properties that stimulate blood flow—which explains why it’s most common use over the years has been as an aphrodisiac. Other studies show that it relieves symptoms of gout and kidney stones. The stems have historically been used to treat skin diseases and the flowers have been used to treat leprosy. An all around versatile plant!

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Cup-shaped

- 5 petals

- Solitary on stems

Seeds:

- Small fruits are spiny

- Fruits break into 5 burrs with spines

- Goes from green to brown

Leaves:

- Oblong

- Small, less than 1in wide or long

- Hairy

General:

- Hairy stems

Here’s how to identify Puncturevine (Tribulus terrestris)

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

Due to it being a non-native plant and an aggressive grower, Purslane is generally considered an invasive plant in most of the US. However, Purslane is edible, if a bit on the sour side, and is a favorite international ingredient! So, if you come across it in the wild, feel free to pull it up and take it home.

Around the globe Purslane enjoys a well-recorded history of medicinal uses. And modern medicine has been able to corroborate many attributes our ancestors said it had! It can be used to help regulate cholesterol and blood sugar levels, it’s a potent anti-inflammatory, and it has antibacterial properties as well. If you’re looking for something to add to your home garden, you might consider keeping this on hand.

Key identification features

Purslane can be confused for Prostrate Spurge (Euphorbia maculata) at first glance. But the stems of Prostrate Spurge are woodier and exude a milky sap when broken. Additionally, the flowers are white instead of yellow.

Flowers:

- 5 petals

- Heart-shaped petals

- Grow in leaf clusters

- Open briefly in the morning

Seeds:

- Black or brown capsules

- Egg-shaped capsules

- Many tiny black seeds in each capsule

Leaves:

- Fleshy and smooth

- Varied in shape

- Can be a bit purple or red

- Cluster at joints and stem ends

General:

- Stems are succulent-like

Here’s how to identify Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

Ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris or Senecio jacobaea)

Ragwort is perhaps one of the most difficult plants to pin down to its scientific name. It has alternates, synonyms, and it shares its common name with plants across several genera. This makes it especially difficult to pin it down as a foraging plant—the species listed here are considered mildly toxic and shouldn’t be eaten in large quantities. But other species of “Ragwort” can be more toxic, so exercise caution when encountering it in the wild.

A nectar-rich plant, Ragwort is highly prized as a food for native pollinators, even in areas where it’s considered a nuisance. Yellow and green dyes can be made from the flowers and leaves respectively, though generally these colors fade quickly after application.

Key identification features

Ragwort can be confused for Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) or Sow Thistle (Sonchus arvensis), both of which are listed below. Tansy leaves tend to look a bit more like ferns and their flowers are in a uniform disc instead of a daisy shape. Sow Thistle, on the other hand, have serrated leaves and flowers with very finely narrow petals.

Flowers:

- Daisy-like

- Form flat clusters at the tops of branches

Seeds:

- 15,000 or more produced per plant

Leaves:

- Pinnated

- Deeply lobed

General:

- Coarse stem

- Purplish-red stem

- Erect stem

Here’s how to identify Ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris)

Rush Skeletonweed (Chondrilla juncea)

Another tricky plant to pin down, Rush Skeletonweed gets its name from the way its leaves look after the plant has flowered: each one dies off and leaves just a “skeleton” of its shape behind. Non-native to the US and highly invasive, Rush Skeletonweed is mostly only looked on favorably by the sheep and goats that enjoy munching on it.

Outside of livestock, people can also enjoy Rush Skeletonweed as a snack during the early rosette stage of its life. In Turkey, where it’s native, the locals extract a chewing gum from the main body of this plant.

Key identification features

Rush Skeletonweed looks similar to another Skeletonweed (Lygodesmia juncea), with the main difference being the plain Skeletonweed lacks a basal rosette and has pink or blue flowers. Tumble mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum) might also look similar, but only once its flowers have matured—every other part of the plant looks different.

Flowers:

- 12 florets

- Toothed petals

- 6-9 petals per flower

Seeds:

- Small, ribbed, achenes

- Soft bristles at one tip of each achene

Leaves:

- Dense rosette of leaves

- Deeply toothed

- Die at flowering

General:

- Leafless stems

- Milky sap

Here’s how to identify Rush Skeletonweed (Chondrilla juncea)

Sow Thistle (Sonchus sp.)

Many varieties of Sow Thistle exist and they look so similar it’s difficult to tell them apart. Fortunately, all varieties are equally invasive in addition to being equally edible! So whether pulling them for food or pulling them for control, you shouldn’t have to worry too much that your pulling the wrong kind, with one exception: Smooth Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus) is considered poisonous to lambs and horses and its roots should be avoided by anyone who is pregnant.

Sow Thistle is best used young as a salad or potherb after the milky sap has been pressed out of it—the sap can turn the plant brown quickly. The sap has been used as a cure for warts, so you can consider keeping some of it on hand instead of throwing it away. Chewing Sow Thistle can help freshen breath. And it’s been used historically to hasten childbirth, and treat skin or eye irritation.

Key identification features

Sow Thistle can look like Ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris or Senecio jacobaea) listed above. The leaves on Sow Thistle can look identical to Wild Lettuce (Lactuca virosa)—check for a row of spines on the underside midrib of Wild Lettuce leaves.

Flowers:

- Small clusters at the tips of stems

- Bloom in the morning

- Numerous ray florets

- Dandelion-like

Seeds:

- Dark achene

- White tufts on the achenes

Leaves:

- Up to 8in long

- Lobed

- Milky sap

- Pinnatifid

- Prickly

General:

- Stem branches at the top

- Hollow stems

Here’s how to identify Sow Thistle (Sonchus sp.)

St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

A cheery plant with vibrant yellow flowers, St. John’s Wort is fairly easy to identify—simply take one of its leaves and hold it up to the light. If it looks like you’re seeing dozens of tiny holes in the leaf, it’s probably St. John’s Wort. Generally considered invasive in the US, the flowers of this plant are so useful it seems a shame that they’ve come to be seen as a nuisance.

The flowers are only considered beneficial when fresh or when used in extracts for longer-term storage. They make for a lovely tea and can be covered with either oil or alcohol to extract and preserve the beneficial effects. As an antibacterial, St. John’s Wort can both clean and help speed wound healing while also reducing scarring. When consumed, some people have reported side effects around fertility, worsening ADHD or bipolar disorders, and reactions with anesthesia drugs.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- 5 petals

- Multiple small flowers per stalk

- Reddish-purple liquid when crushed

Leaves:

- Appear to have tiny holes

- Narrowly ovate

- Tiny

Here’s how to identify St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

Tansy is a fun plant to look out for—the button-like flowers are so unique they almost pop out at you from the undergrowth. Native to Europe and Asia, it was brought over to the US as a medicinal plant. The leaves and flowers are fragrant and are most commonly enjoyed when brewed into a lemony tea, as a garnish, or as a replacement for nutmeg or cinnamon.

However, recent studies have shown that Tansy can be poisonous to humans when eaten in large quantities. There have even been reports of deaths from particularly strong teas made from Tansy. It is no longer recommended for internal use and even external uses are cautioned against.

Key identification features

Tansy can look similar to Ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris or Senecio jacobaea), which is listed above along with the differences between the two plants.

Flowers:

- Disc-shaped

- Button-like

- Clusters of 20-200 flowers

Seeds:

- 5 brown achenes grow together

Leaves:

- Soft

- Feathery and fern-like

- Smell like Camphor when crushed

Here’s how to identify Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

There was a time when Wild Mustard was considered a non-native, extreme nuisance by farmers. It would invade crop fields and home gardens in what seemed like the blink of an eye. Today it isn’t considered nearly as much of a threat and is under control enough that it only becomes bothersome to gardeners wanting to keep it out.

But there’s not much need to keep it out of gardens—it’s a host plant for butterflies and a highly edible plant. Young leaves from Wild Mustard have a spicy flavor and make an excellent addition to salads. The flowers taste a bit like cabbage or a radish and can be used as a vegetable or garnish. The seed pods are edible, but the oils from them are perhaps more useful in making soaps, oils for cooking, or lubricants for machines.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Star-shaped

- 4-5 petals

- Blooms from late spring to early fall

Seeds:

- Round pods below the flower head

- As the flower dies, the pod elongates

Leaves:

- Varied in shape

- Edges are serrated and dented

Here’s how to identify Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

Wild Radish (Raphanus raphanistrum)

Wild Radish enjoys being both highly invasive and highly edible—creating a bit of tension in how it’s seen in its non-native habitats. All tender parts of the plant can be eaten and the leaves and flowers add a bit of a spicy flavor to whatever they’re paired with. At one point it was even cultivated as a potential substitute for horseradish! While the roots are a bit too tough to be edible, when washed and peeled, the peels can be eaten raw or cooked.

Key identification features

The flowers of Wild Radishes look similar to the flowers of the American Searocket (Cakile edentula). You can check for thinner, woodier stems to see if you’re actually looking at an American Searocket.

Flowers:

- 4-5 petals

- Dark veins under the petals

Seeds:

- Green to purple pods when young

- Yellow, brown, or gray pods when mature

- Pods are erect on stalks

- Red-brown egg-shaped seeds

Leaves:

- Blue to green

- Rough to the touch

- Pinnately divided

- Basal rosette

Here’s how to identify Wild Radish (Raphanus raphanistrum)

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

Perhaps one of the most culinarily diverse plants on this list, Wild Parsnip isn’t as showy as you might expect. You’ll spot it growing in sunny areas (it doesn’t like shade), and on many states’ invasive species lists. Be sure to wear gloves and long sleeves when handling any part of this plant. When the sap comes in contact with skin and sunlight it can cause severe burns and blisters to develop.

Once safely brought inside, the fun side of Wild Parsnip can show itself. The leaves, stems, and flowers can be treated like any other vegetable and are best when young. Later in the year, the seeds can be harvested as a seasoning similar to dill in flavor. But the root is really where this plant shines: it can be eaten raw, in soups, is delicious when baked, and can even be added to deserts! Harvest the root after the first frosts have set in for a sweeter flavor.

And that’s not even where the uses for the roots end: they’re also the part of the plant used medicinally. A poultice can be used to treat inflammation or sores. And teas made out of the roots have been used to treat a variety of symptoms in women’s health.

Key identification features

Wild Parsnip can be confused with Golden Alexander (Zizia aurea) and Prairie Parsley (Polytaenia nuttallii)

Flowers:

- 5 curled petals

- Greenish yellow centers

- Grow in clustered umbels

Leaves:

- Basal rosette

- 9 leaflets per leaf

- Large, up to 18in long and 6in wide

General:

- Angular, hollow stems

Here’s how to identify Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

Wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris)

A neat plant with delicate, clustering flowers, Wintercress will happily grow throughout the year if in an area with mild winters. Unlike many plants on this list, while a bit weedy in how rapidly it grows, Wintercress isn’t considered invasive despite being a non-native. In areas where Diamondback Moths are a problem, it’s actively being planted as a trap plant to control caterpillars that would otherwise wreak havoc on cabbages.

Young leaves of Wintercress can be eaten raw or cooked, as can the flowers and their buds. As a medicinal plant, it has historically been used to treat coughs, and the leaves can be applied to wounds. When eaten, the leaves can act as a vitamin-c booster, aid in digestion, and provide a mild diuretic effect. Be careful to consume small quantities of Wintercress as large amounts have been shown to affect kidney function.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- 4 petals

- 4 green sepals

- Grow in clusters towards the tops of stems

Seeds:

- Pods develop below the flower heads

- Ovoid, slightly flattened seeds

Leaves:

- Glossy

- Undulating margins

- Lightly lobed

- Obovate in shape

General:

- Stems are ribbed

Here’s how to identify Wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris)

Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.)

A cheerful summer weed in many parts of the US, Wood Sorrel makes for an excellent backyard snack. With leaves tasting similar to cucumbers or lemons (it’s just a bit on the sour side), they can be gathered and eaten as a quick refreshment.

When brought inside the leaves and roots can be used to make everything from sorbets to potato salads to cold drinks or teas! You’ll need to work hard to exercise moderation with this plant—in excess it can cause kidney stones or inhibit your body’s ability to absorb nutrients.

Medicinally, Wood Sorrel can be turned into a poultice to treat inflammation and cool skin or made into a tea to soothe stomachs. Additionally, a yellow or orange dye can be made if you boil the entire plant.

Key identification features

Wood Sorrel can be confused with Clovers in the (Trifolium genus) but can be distinguished by leaf shape. Clovers have round leaves instead of the heart shapes made by Wood Sorrel.

Flowers:

- Bloom year-round in warm climates

- 5 petals fused at the base

Seeds:

- Okra-like pods

- Explode when ripe

Leaves:

- Heart shaped leaflets

- Creased down the middle

- 3-4 leaflets per stalk

- Fold in dim to dark light

General:

- Thin, smooth stems

- Grows in clumps

Here’s how to identify Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta)

Yellowcress (Rorippa spp.)

While not all subspecies of Yellowcress are considered weeds, two in particular are considered invasive in North America: Great Yellowcress (Rorippa amphibia) and Creeping Yellowcress (Rorippa sylvestris). Both look highly similar to other plants in the species that are native and non-invasive. If you’re worried you may have an invasive variety nearby, check with a local plant expert.

Most Yellowcress plants are edible and can be an excellent substitute for Watercress in any recipe. Creeping Yellowcress is not listed as a toxic plant, but neither is it commonly listed as edible—so it may not be the most palatable choice for your salads.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Tall, branching flower stalks

- Tiny flowers

- Grow at the ends of branches

Seeds:

- Cylindrical fruit

- Fruit contains several tan seeds

Leaves:

- Deeply lobed

- Basal rosette

- Pinnate

Here’s how to identify Yellowcress (Rorippa palustris)

Yellow Bedstraw (Galium verum)

While some invasive plants might be desirable in gardens due to how useful they are, Yellow Bedstraw is so invasive it actually outweighs the benefits of having it around. Keep an eye out for it when you’re walking and hiking in sunny areas—not only to potentially gather it, but also to make sure you don’t pick up any of its bristly fruits.

As a type of straw, Yellow Bedstraw can be used to stuff pillows or beds, and when camping can be bundled together to make a strainer. Today you could consider making a sachet out of them to use to repel fleas from areas your pets frequent. You can even use the plant to make red paints or yellow dyes.

Yellow Bedstraw also has medicinal and culinary uses. Flowers harvested from Yellow Bedstraw can be used to both coagulate and color cheese. In Denmark the plant is used to infuse spirits for traditional drinks. Tinctures made from the plant can be used as a diuretic and to treat UTIS.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Tiny

- 3-5 curly petals

- Grow in pointed clusters

Seeds:

- Black, bristly pods

- Seed pods split open when ripe

- Single seed per pod

Leaves:

- Narrow and pointed

- Hairy

- Grow in groups of 8-12 leaves

General:

- Some erect stems, generally sprawling

Here’s how to identify Yellow Bedstraw (Galium verum)

Yellow Goatsbeard (Tragopogon spp.)

You might not be able to spot Yellow Goatsbeard right away when it’s young. During the first year of its life, it looks like just another clump of grass in meadows and along highways. Not until the flower stalk appears in the second year does it become apparent what it is.

Originally brought over as a garden plant to the US, Yellow Goatsbeard now grows wild, is considered invasive, but isn’t aggressive enough to be a major ecological threat. This may be due, in part, to how palatable it is to native wildlife—everything from cows to birds to bears enjoys feasting on this plant.

For people, the young leaves, roots, and stems are edible raw or cooked. Poultices made from Yellow Goatsbeard have been used to treat animal bites and boils. And you can make a chewing gum out of the coagulated milky sap extracted from the stems and leaves. It’s a versatile plant and may even be worth adding to your pastures or your own home garden!

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Daisy-like

- Solitary flowers at the end of stalks

- Numerous ray florets

- 5 small teeth on each petal

- Open in the morning

- Closed in the afternoon

Seeds:

- Similar to an extra-large dandelion head

Leaves:

- 1st year basal rosette

- Rosette dies in 2nd year

- Lanceolate with smooth edges

General:

- All parts exude a milky latex

Here’s how to identify Yellow Goatsbeard (Tragopogon spp.)

Yellow Nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus)

Incredibly difficult to remove once it’s established, Yellow Nutsedge is a native nuisance in much of the US. When growing alongside other plants, it robs them of their nutrients and is capable of developing new root systems from fragments of broken roots. However, despite its current status as a weed, Yellow Nutsedge is among one of the longest cultivated plants on earth with records showing it was a key food crop in Ancient Egypt.

Yellow Nutsedge forms striped nodes on its roots that are commonly called tiger nuts. These are tender, sweet, and do actually have a nutty taste to them. There are a multitude of ways it can be used: baked, roasted, dried, pressed for oil, or made into drinks. In fact, in Spain, tiger nuts were used to make the original form of the popular Latin American Horchata drink.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Clusters arising from a common point

- 10-30 florets per spikelet

- Spikelets at the end of stems

- 4 ranks of spikelets along the stalk

- Spikelets are perpendicular to the stalk

Seeds:

- Small oblong achene

- Single seed in each achene

Leaves:

- V-shaped

- Glossy

- Narrow

- Channel running through the middle

- Located towards the base of the plant

Here’s how to identify Yellow Nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus)

Yellow Toadflax (Linaria vulgaris)

Yellow Toadflax is a delicate looking plant with the most robust root system on this list. Growing up to 10ft in diameter, roots can produce daughter plants all along their lengths, leading to the formation of dense strands of Yellow Toadflax. For this reason, and because it isn’t native to North America, it is considered highly invasive.

Originally cultivated in Germany, Yellow Toadflax was primarily harvested as a source of yellow dye. It has a long history of being used as a diuretic to treat oedema, but should be taken in small doses and avoided entirely by pregnant women. Best used just as it’s beginning to flower, you can collect the whole plant and use it fresh or dried. Ointments made from Yellow Toadflax have been applied to sores, hemorrhoids, and piles.

Key identification features

Flowers:

- Snapdragon shaped

- Yellow edges with an orange throat

- Thin spurs are the base

- Grow in spiked clusters

Leaves:

- Gray or silver tinge

- Pointed at the tip

- Thread-like

Here’s how to identify Yellow Toadflax (Linaria vulgaris)

Wild Weed Identification Guides

Looking for more guides to help you identify (and use) the wild weeds all around us?

- Weeds with Purple Flowers

- Weeds with Orange Flowers

- Weeds with White Flowers

- Weeds with Blue Flowers