Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Hop hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana) is a lesser-known understory tree that quietly populates hardwood forests across eastern North America. Often mistaken for a weed by foresters, it produces distinctive hop-like seed clusters in late summer and fall that reveal tiny edible seeds inside. Though the tree won’t help you brew beer, it offers food, medicine, and exceptional firewood for those who take the time to get to know it.

Table of Contents

- What is Hop Hornbeam?

- Is Hop Hornbeam Edible?

- Hop Hornbeam Medicinal Benefits

- Where to Find Hop Hornbeam

- When to Find Hop Hornbeam

- Identifying Hop Hornbeam

- Hop Hornbeam Look-Alikes

- Eastern Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana)

- American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana)

- European Hop Hornbeam – Ostrya carpinifolia

- Japanese Hop Hornbeam – Ostrya japonica

- Chinese Hop Hornbeam – Ostrya rehderiana

- Ways to Use Hop Hornbeam

- Hop Hornbeam Recipes

- Foraging Guides

If you’ve ever noticed what looked like papery hops growing on a tree while hiking in the woods, you may have stumbled across hop hornbeam. These hop-like clusters aren’t from a vine, but from an understory tree that thrives in shaded forests throughout the eastern U.S.

While the “hops” aren’t useful for brewing, they enclose small edible seeds—an often-overlooked wild food source and a reliable tree to identify if you’re a forager, woodcrafter, or herbalist.

What is Hop Hornbeam?

Hop hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), also known as ironwood, leverwood, and deerwood, is a small deciduous tree native to eastern North America. It’s most often found as a slow-growing understory tree in hardwood forests. While it can grow up to 50 feet tall and 2.5 feet in diameter, most specimens stay under 30 feet and less than a foot thick. Its growth habit is often crooked or leaning, and it typically inhabits mixed forests alongside linden, ash, and hemlock.

This hardy species is often overlooked by foresters in favor of faster-growing, more commercially valuable trees. But for those of us who appreciate resilience and utility, hop hornbeam is anything but useless.

Is Hop Hornbeam Edible?

Yes, the small seeds inside hop hornbeam’s hop-like catkins are edible. They’re about the size of a sunflower seed and can be eaten raw or dry-roasted. Birds and small woodland mammals rely on them as a food source, and foragers can enjoy them too—though they’re tiny, they’re easy to collect in quantity when the tree is producing heavily.

The seeds form in early summer but aren’t ready until the husks dry out in the fall. Collect them from the ground or directly from the tree starting in mid-October, and look for a firm, dark tan seed rather than greenish immature ones.

Hop Hornbeam Medicinal Benefits

Hop hornbeam is a medicinal tree with a number of traditional uses, particularly among Indigenous North American groups. According to Native American Ethnobotany by Daniel Moerman, infusions or teas made from the bark were used as topical treatments for sore muscles, arthritis, and toothaches. Full-body baths with bark decoctions were used to relieve pain and inflammation.

Though not widely studied in modern pharmacology, the use of hop hornbeam as a mild analgesic and anti-inflammatory aligns with its traditional applications. Its bark contains tannins and other astringent compounds commonly found in medicinal tree species.

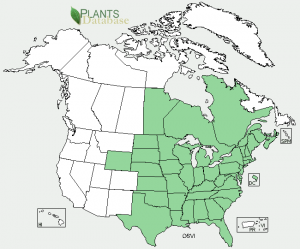

Where to Find Hop Hornbeam

Hop hornbeam is widespread across the eastern United States and southeastern Canada. It grows in a wide range of conditions but prefers moist, well-drained soils and is most often found in deciduous forests, especially on slopes and rocky hillsides. It commonly grows alongside hemlock, ash, maple, and linden in forest understories.

When to Find Hop Hornbeam

The hop-like seed clusters first appear in late spring to early summer, when they are green and unripe. By July and August, you’ll begin seeing the first dry husks on the ground, but the seeds are often still immature. The best time to harvest ripe seeds is mid to late October, depending on your region. Look for trees where the papery catkins have fully dried and the seeds inside are firm and tan-colored.

Identifying Hop Hornbeam

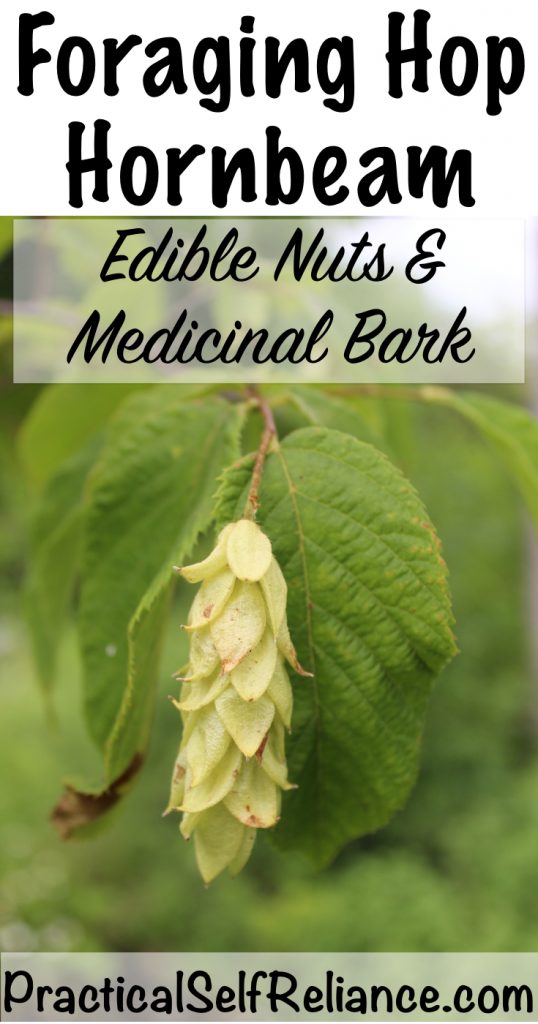

Hop hornbeam is easy to recognize once you’re familiar with a few key features. The tree has a slender, often crooked trunk, with narrow strips of bark that peel slightly at the ends. The standout feature is its fruit: clusters of papery seed pods that strongly resemble hops.

Hop Hornbeam Leaves

Leaves are simple, alternate, and oblong, ranging from 2 to 4 inches long. They have fine serrated edges and are slightly fuzzy beneath. The leaf shape is similar to birch but narrower and more lance-shaped.

Hop Hornbeam Bark

Young stems are slender and reddish, while older branches and trunks are coated in thin, vertical strips of bark that appear to lift slightly at both ends. This flaky bark helps distinguish it from related species.

Hop Hornbeam Flowers

Hop hornbeam is wind-pollinated and produces inconspicuous male and female catkins in spring. Male catkins are long and dangle, while the female flowers are less noticeable but give rise to the seed clusters.

Hop Hornbeam Fruit

The fruit is a cluster of papery, hop-like bracts, each enclosing a small edible seed. When green, they’re immature and soft, but by fall they dry to a light tan or brown, with the seed inside hardening to almond or sunflower seed texture.

While the bark is distinctive, the hop-like catkins make this tree easy to identify in the summer and fall. The Sibley Tree Book describes them as “a cluster of pointed papery bladders, each enclosing a seed.”

Hop Hornbeam Seeds

As a woodland forager, I was excited to learn that the catkins contain wild edible nuts that are an important source of food to birds and small woodland mammals, and a tasty snack for humans. They’re quite small, about the size of a sunflower seed.

The good news is crops of hornbeam catkins can be heavy, and they’re easy to find and collect from the forest floor. They can be eaten raw, or dry roasted in a pan.

The seeds in the image below are a bit under-ripe.

When the pods are collected from the ground, check for a dark tan seed rather than those with a hint of green like below in the picture. If collecting directly off the tree, wait until Mid-October to begin checking for ripeness in your area.

Hop Hornbeam Look-Alikes

Ostrya virginiana (Eastern Hop Hornbeam) and Carpinus caroliniana (American Hornbeam) are often confused because they’re both small understory trees in the birch family (Betulaceae), and both are sometimes called “ironwood.” But they’re quite different once you know what to look for:

Eastern Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana)

- Bark: Shaggy, with narrow, vertical strips that peel off like cat scratch marks.

- Leaves: Doubly serrated, birch-like, alternate on the stem.

- Fruit: Hanging clusters of papery sacs that resemble hops (hence the name).

- Wood: Extremely hard and dense—hence the nickname “ironwood.”

- Form: More upright and narrow; often found on dry, rocky slopes.

- Fall Color: Yellow to brown, not especially showy.

- Range: Widespread in eastern North America, including the entire Northeast.

American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana)

- Bark: Smooth, gray, and fluted—looks like muscle tissue, earning it the nickname “musclewood.”

- Leaves: Also doubly serrated and birch-like, but often glossier and a bit darker green.

- Fruit: Small nutlets in leafy, three-lobed bracts; not hop-like.

- Wood: Also very hard, but not as dense as Ostrya.

- Form: Broad, spreading shape; prefers moist, shady forests near streams.

- Fall Color: Can be quite striking—orange, red, or yellow.

- Range: Eastern North America, thrives throughout the Northeast, especially in rich, moist woods.

Beyond American Hornbeam, Eastern Hop Hornbeam can be easily confused with other Ostrya species, but none of the others are native to the Northeast US.

European Hop Hornbeam – Ostrya carpinifolia

- Native to southern and central Europe.

- Often planted as an ornamental tree in temperate regions.

Japanese Hop Hornbeam – Ostrya japonica

- Native to Japan and parts of Korea and China.

- Sometimes used ornamentally.

Chinese Hop Hornbeam – Ostrya rehderiana

- Very rare and critically endangered.

- Native to China (only a few wild specimens known).

Ways to Use Hop Hornbeam

The seeds can be eaten raw or roasted, though they’re small. In heavy production years, it’s possible to gather large handfuls from beneath a tree in minutes. They have a mild, nutty flavor and are best eaten as a trail snack or dry pan-roasted.

The bark and wood have traditional medicinal applications for aches, inflammation, and oral health. Infusions were used for full-body soaks or applied topically.

Beyond foraging, hop hornbeam is valued for its hardwood, which burns hot and long. In fact, old Vermonters caution not to fill the wood stove with too much ironwood at once—it can overheat even a large stove. The wood was traditionally used for sleigh runners and tool handles.

Hop Hornbeam Recipes

There are no formal culinary recipes using hop hornbeam seeds, but foragers use them in simple, direct ways. Roasted Hop Hornbeam Seeds can be prepared by dry-toasting the seeds in a cast iron skillet over low heat until lightly browned and fragrant. They can be enjoyed whole, ground into a coarse meal, or added to foraged trail mixes.

Foraging Guides

If you’re gathering hop hornbeam seeds, keep an eye out for other edible wild fruits maturing in late summer and early fall. Rowanberries grow in similar forested areas and are perfect for preserves. Hawthorns often share habitats with hornbeam and offer tart red fruits with heart-supporting properties.

In sunny openings, you might find wild black raspberries and northern dewberries, both excellent for fresh eating or jam-making. Wild gooseberries grow in cooler understories and produce tart, seedy berries often used in pies. And don’t overlook wild strawberries, which ripen earlier but may still be fruiting in shaded, cool forest edges.

Thirty years after moving to this house, one day I noticed a tree with these catkins in a copse growing between cracks the ledge that underlies our neighborhood. I had never noticed it before, and was quite excited with this find. But this year I don’t find any catkins at all. Is there something I can do next year to get it to produce? Is there something wrong with my tree?

Many wild trees have boom and bust years, and they go in natural cycles. In biology, a heavy year is called a “mast year” where a tree will overproduce so that there’s way more than the predators (ie. Squirrels) can eat. Then they’ll produce nothing, just to keep the predators on their toes. To the best of my knowledge, there’s not a whole lot you can do to make them produce more regularly, except possibly thinning the crop in heavy years like you’d do with apples.