Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

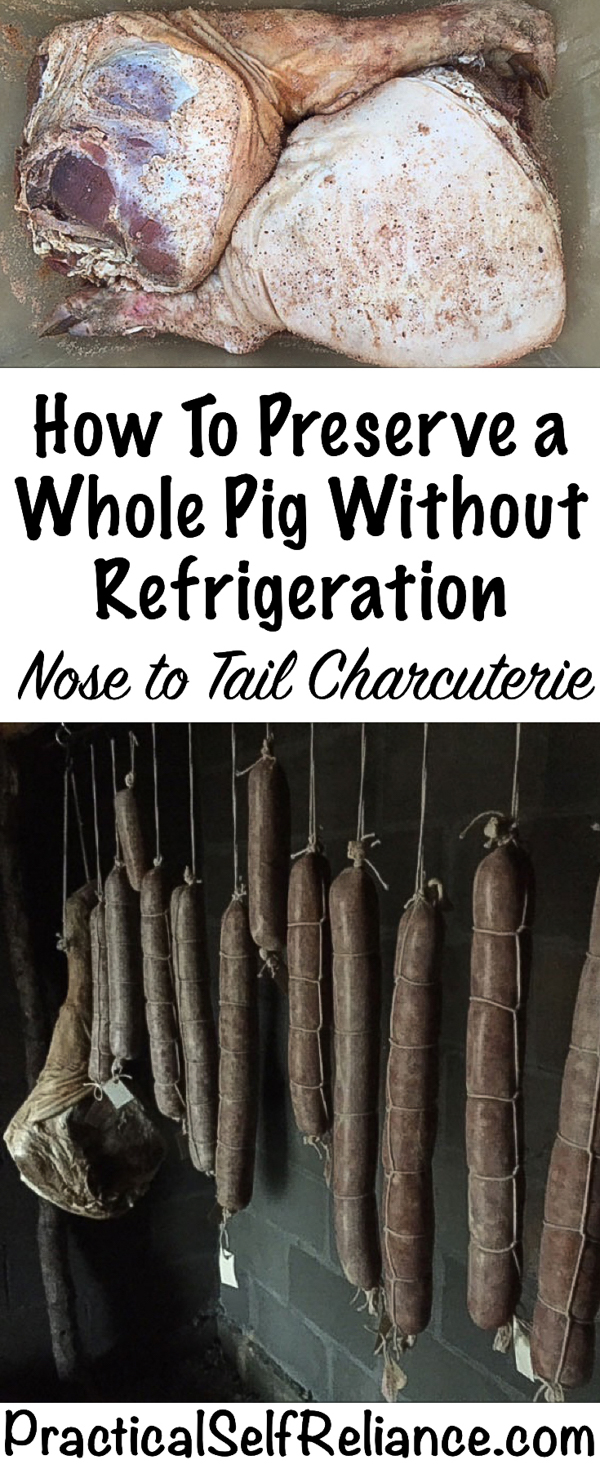

A pig is a large animal, capable of providing meat for a family for the better part of a year properly preserved. These days, we freeze most of our meat to keep it from spoiling, but refrigeration has only been around for the past century or so.

How did our great-grandparents, and countless generations before them, preserve pork meat?

Table of Contents

- Resources for Preserving Pork Meat

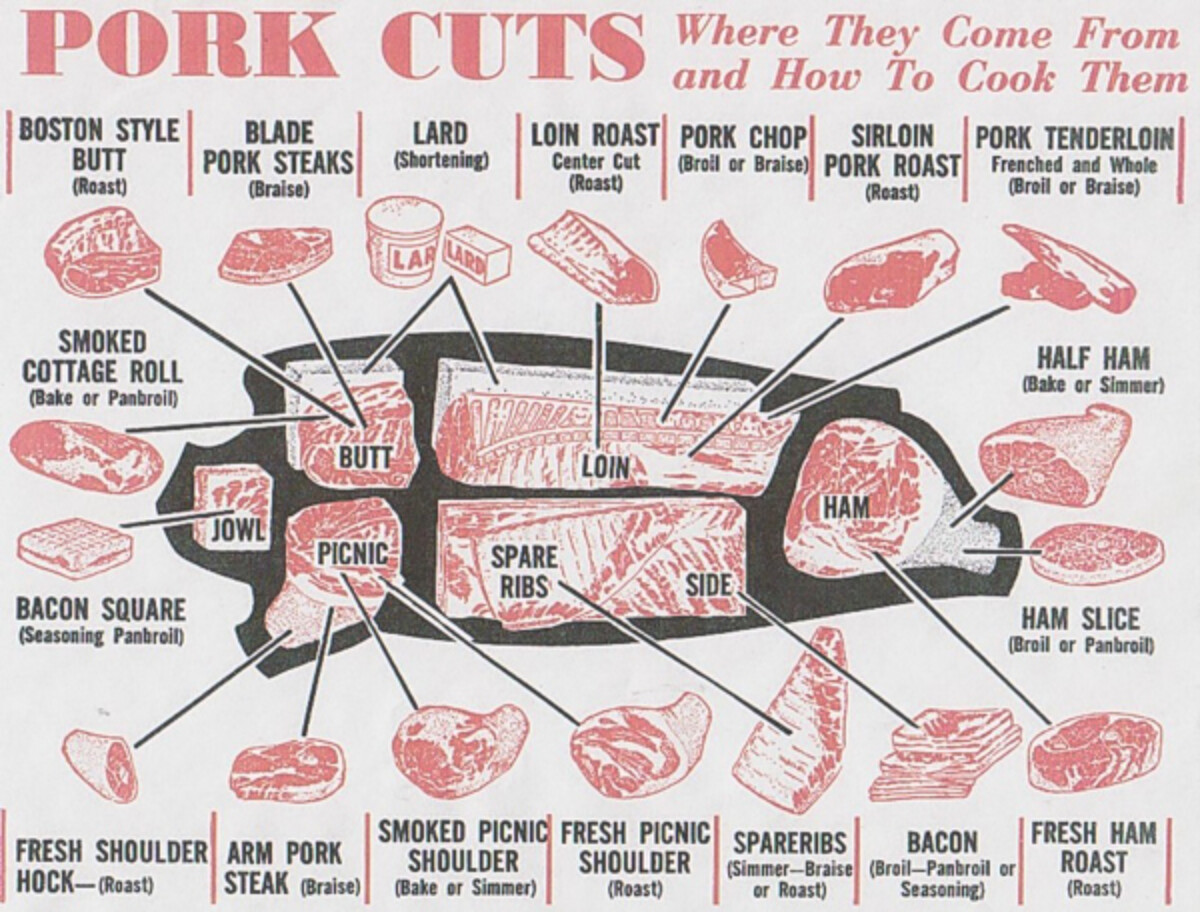

- Best Preservation Methods for Each Pork Meat Cut

- Cured Pork Leg

- Cured Pork Loin

- Cured Pork Tenderloin

- Cured Pork Shoulder (Salumi)

- Cured Pork Neck

- Cured Pork Belly

- Cured Pork Jowls

- Cured Pork Ribs and Trimmings

- Using Pig Head, Shanks, and Trotters

- Preserving Different Types of Pork Fat

- Preserving Pork Bones as Stock

- Final Thoughts

- More Traditional Food Preservation Guides

I began researching preservation methods a few years ago, hoping to home process a hog and preserve it using traditional methods. Right after we got that year’s pigs, I became pregnant with my first child and I learned just how hard it is to put food on the table while growing a family.

Our pigs were still processed at home, but later than expected. They were almost a year old and about 350 pounds each. Sadly, feed conversion really drops off once they start getting that large, dramatically increasing how much it costs to raise a pig.

It’s also a lot harder to butcher them. It took us all day to just get them into the freezer, with an 8-week old baby slung on my back while we worked.

It was all we could do to get them put up, and we weren’t up for adding any extra challenges to our day. Our two 350 pound pigs had a dressed weight of about 175 pounds each. It’s a good thing we have 3 chest freezers…

Though it didn’t work out this time, my pork preserving research will not go to waste. We still plan to preserve a whole pig without refrigeration in the next few years. In the meantime, I’ve been working through each pork cut, a few at a time each year.

We’ve made pancetta with the belly, guanciale with jowls, made literally hundreds of pounds of cased sausage, rendered lard for the pantry, and much more.

I’ve found methods for almost every part of the pig, but there are a few that still a few parts that remain elusive.

I have yet to find traditional methods for the long-term preservation of pork ribs, for example. There are a few traditional southeast Asian methods for fermenting the meat, but only for a short period before consumption. For now, I plan to preserve the rib meat as rillettes and cook the bones down for pressure-canned pork stock.

In order to preserve a whole pig without refrigeration, I’m still going to fall back on a few modern methods, including canning. Nonetheless, those methods still don’t require electricity, and modern or not, they can still be accomplished with little more than a bit of equipment and a fire pit.

Resources for Preserving Pork Meat

Before you get started, you’ll need the right tools. Very sharp and purpose-built knives are essential to parting up a pig at home, especially if you plan to end the day with all your fingers still attached.

Cutting with a dull knife, or the wrong type of knife for the job is a good way to get hurt. Here’s a list of the knives we use on processing day:

- 6-inch Boning Knife with Flexible Blade – For cutting around joints and along bones like the shoulder blade.

- 12-Inch Butcher Knife with a Rounded Tip – Perfect for long cuts like separating out ribs.

- 5-inch Skinning Blade – Essential if you’re skinning a pig, but also helpful in separating layers between cuts.

- 22-inch Stainless Steel Meat Saw – Not exactly a knife, but a must for cutting through bone.

Beyond good tools, you’ll need a few key supplies. If you’re adventurous, you can clean your own pork casings for sausage. If this is your first time making sausage, however, I’d suggest practicing with store-bought casings to get the process down before you add that extra complexity.

Curing salt, as well as regular kosher salt, are also must-haves for long-term preservation. (Here’s a curing salt calculator to help you determine how much to use.)

You’ll also need a meat grinder, either electric (we use this one) or hand-powered, and a sausage stuffer.

If you’re seriously considering raising and preserving a whole pig at home, I’d also suggest investing in a few charcuterie books. If you’re only going to buy one, I’d suggest starting with Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking, and Curing. It’s comprehensive and written in easy to understand language with lots of recipes included.

Here’s what’s on my charcuterie shelf in my home library:

- Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking, and Curing

- The Art of Making Fermented Sausages

- The River Cottage Curing and Smoking Handbook

- Olympia Provisions: Cured Meats and Tales from an American Charcuterie

- Meat Smoking and Smokehouse Design

Best Preservation Methods for Each Pork Meat Cut

We’re used to using each cut of pork differently in our cooking. Some cuts are tougher, and are better roasted low and slow, while others are better for quick grilling. In pork preservation, each cut has different characteristics that affect the final flavor of the product.

Tougher and fattier cuts can be ground into sausage that’s preserved in casings, while leaner or more tender cuts may be salted and preserved whole.

Cured Pork Leg

The back legs of the pig get less work than the shoulder and the meat is more tender. The whole leg is often cured as one piece, into either a type of ham or prosciutto. The process involves thoroughly salting the entire leg, and then curing for a year or more.

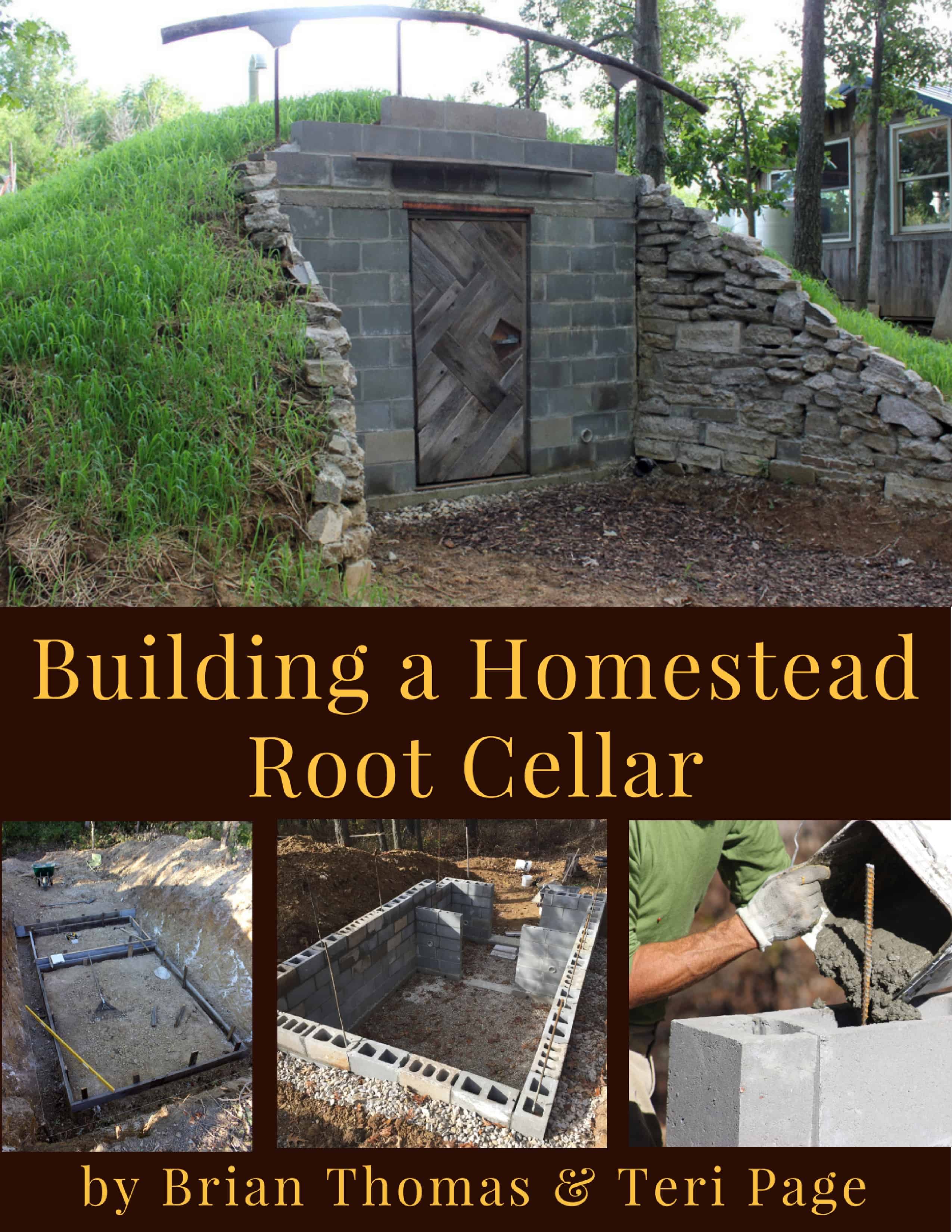

Since it’s such a big cut of meat, it can be risky if you don’t have the temperatures just right. Only curing a ham or prosciutto at home if you have an appropriate root cellar or consistently cool basement.

My friend Teri at Homestead Honey built a root cellar (and wrote a book about the process) and home-cured prosciutto was one of the first things that went in.

She wrote about her adventures in homestead meat curing, where they cured prosciutto, lardo, salami, and bacon on their homestead in Missouri.

Beyond that, here are a few recipes to use the back legs of a hog:

Cured Pork Loin

Coming back from the dark neck meat is the lightly colored pork loin. When the back fat is left on, this becomes pork chops.

Totally stripped of back fat and rib bones, this cut becomes a single long loin cut. There are a number of different regional ways to cure a pork loin.

The Italians make it into lonzino with a bit of salt, sugar and instacure #2 along with black pepper, garlic, cloves, and thyme.

Canadian bacon and German kassler are also made from the pork loin, but it’s a fresh cure that won’t keep the same way that lonzino will.

- Hunter Angler Gardener Cook – Lonzino, Air Cured Pork Loin

- Foodie with Family – Maple Cured Canadian Bacon

- The Spruce – German Kassler Cured Pork Loin

Cured Pork Tenderloin

The tougher parts of the pig are the parts that a pig uses every single day for basic motions. Good examples are the jaw and jowl muscles for chewing and the neck muscles for rooting. The tenderloin is just the opposite.

It’s a small muscle that pulls the pig’s back legs forward as it moves. For the most part, that’s a passive action, and that muscle hardly ever contracts. Lack of use makes a tenderloin exceptionally tender and smooth meat.

If you can, roast the tenderloin up the day you process the pig for a real treat. It’s quick-cooking and prepares without much fuss. There’s nothing better than a succulent tenderloin after a long day spent processing a pig to remind you why it’s all worthwhile.

If you do choose to preserve the tenderloin with the other cuts, there are a few things to keep in mind. Tenderloins are much smaller and even leaner than pork loins. They can be cured quickly and easily at home as a whole cut.

- Two Guys and A Cooler – Calabrian Pork Tenderloin

- NYT Cooking – Cured Pork Tenderloin Ham

- Mother Earth News – Cured Pork Tenderloin

Cured Pork Shoulder (Salumi)

The pork shoulder is almost always ground into sausage for salumi. Why? The shoulder is one of the most used groups of muscles on a pig, and it tends to be tough and fibrous.

It also happens to have the perfect proportion of fat to meat for most sausage (20% fat and 80% meat). Since the shoulder is heavily used, it also has more flavor than most cuts, which yields exceptional sausage.

There are literally hundreds of different types of cured sausages. They vary in size, curing time, seasoning, and most importantly, flavor.

They all use lactic acid bacteria, the same bacteria that makes sauerkraut and kimchi, to consume the sugars within the meat and lower the pH so that harmful pathogens cannot thrive. To do this wonderful preservation work, they need salt.

Salt added at the beginning of the process slows down the growth of harmful bacteria and gives the lactic acid bacteria a competitive advantage. For an in-depth tutorial on home-cured sausages, The Art of Making Fermented Sausages is the best resource around. It covers every aspect of sausage making and explains in detail how and why each step work to preserve the meat (along with troubleshooting guides).

If you’re considering building your own smokehouse, as many types of cured meat and sausages are smoked, I’d highly recommend Meat Smoking and Smokehouse Design by the same author.

To make salami, you first have to make sausage. That involves grinding the meat and then getting it into casings with seasoning and salt.

We use a LEM 3/4 hp meat grinder, and it makes beautiful mince for sausage at the rate of 7 pounds per minute. You can also use a hand grinder, which will give you a good workout and let you accomplish the same thing without electricity.

Regardless of how you grind the sausage if you plan to cure the meat DO NOT use the meat grinder to pack your sausage into casings. Putting the meat back through the meat grinder emulsifies the meat and sausage bits, leaving you with something akin to hot dogs or bologna. Good quality salumi is made with a sausage stuffer, that does not mash and emulsify the meat as it goes into the casing.

Homestead Honey has beautiful pictures (and a tutorial) for making sausage at home using an 8-quart sausage stuffer after manually grinding the meat in a hand grinder.

- Hunter Angler Gardener Cook – Italian Cacciatore Salami

- Hunter Angler Gardener Cook – Fennel Salami

- Hunter Angler Gardener Cook – Kabanosky, polish smoked meat sticks

Cured Pork Neck

Capocollo is an Italian word that directly translates to “top of the neck.” That’s just where this cut comes from.

When cutting up a pig, you can easily see that the loin that runs above the ribs and outside of the spine changes color near the neck. Starting at the 4th or 5th rib, the loin meat abruptly changes from white meat pork to the much darker color of the collo or “collar” meat.

Because the Italian language varies by region, it’s also called capicollo, capicollu, finocchiata. In Argentina, they call it bondiola or bondiola curada. In the US we typically call it capicola or capicolla.

The main difference between preparing capocollo and many other cured whole pork cuts is that capocollo is cased in a large casing as a whole cut. Since this adds considerable complexity to the process, the neck meat is sometimes just ground into sausage with the shoulder meat. It can also be cured in a similar manner to the pork loin, though the texture, flavor and fat content will be very different.

After the meat goes into a large casing, it’s then tied using a number of complicated butchers knots to secure it along the whole length of the cut. These days, butchers and home curers alike use meat nets to simplify the process.

- Cured Meats: The Art and Craft – Capocollo di Calabria

- Living Italian Style – Guide to Homemade Capicollo

Cured Pork Belly

Everyone knows that pork belly is for making bacon. The trick is, not every culture makes bacon the same way. American bacon was cured and hot smoked to be shelf-stable as pioneers moved across the open plains.

Italians make a completely raw version called pancetta that’s rolled and hung to cure with aromatic spices.

The French also have a version, called ventreche.

Other cultures have their own version too, so really just a small amount of digging and you’ll find plenty of ways to cure pork belly.

- Ann’s Entitled Life – How to Cure and Smoke Your Own Bacon

- Christina’s Cucina – How to Make Pancetta

- Bacon is Magic – How to Make Pancetta in 60 Seconds

- Hunter Angler Gardener Cook – Ventreche, French Bacon

- Hunter Angler Gardener Cook – German Bacon

Cured Pork Jowls

Cured pig jowl, or Guanciale, is cured meat somewhat like pancetta, but more flavorful. A pig really uses its jowl muscles, which means that they’re tough but flavorful.

The curing process renders them tender but maintains all the rich flavor. The pig jowl is cured in a mix of instacure #2, salt, sugar and spices for about a week until it’s stiff. It’s then washed off and hung to dry at 50 to 60 degrees and 55% humidity for at least 3 weeks.

Cured Pork Ribs and Trimmings

I’ll admit it, I haven’t found a good way to cure pork ribs. My best solution is to either cook them immediately or to bone the meat off and cure it in pork fat as confit.

Confit is salt-cured meat, slow-cooked in fat directly in a preservation vesicle, like an earthenware pot. When it cools, the fat seals the top and keeps oxygen out, effectively protecting the sterilized cooked meat inside.

Kept in a cool dark place, confit, or potted pork should keep for months. Rillets are a similar dish but made with shredded meat off the bone preserved under a layer of pork fat.

We’ve made duck confit many man times, as well as duck rillets. The process is no different for pork.

Using Pig Head, Shanks, and Trotters

Though head cheese is not a preserve or cure, it is an excellent way to make use of the little bits of meat and rich gelatin found in the head, shanks and trotters. The yield is relatively small, and it’s one of those things to eat within a few days of processing a pig. Hank Shaw at Hunter Angler Gardener Cook describes the process in a nutshell:

“hog’s head and a few trotters simmered with herbs, veggies, and spices until the meat — and everything else — falls off. You then pick through the bits for the goodies, strain and reduce the stock and rely on the gelatin in it to set the sausage.”

Hank also describes in detail why it really shouldn’t be called head cheese, but hey, that’s what it’s called in this country. It may not be an appetizing name, but it does make a tasty meal.

- Hunter Angler Gardener Cook – Copa di Testa (head cheese)

- Hunter Angler Gardner Cook – Fromage de Tete (French Head Cheese)

- Kopiaste (to Greek Hospitality) – Zalatina (Greek Head Cheese)

Preserving Different Types of Pork Fat

Pork fat is one of the easiest parts to preserve. If properly rendered, lard will keep in a cool pantry without refrigeration. Meats preserved in pork fat, such as rillets and confit, will also keep in a cool cellar without canning.

How to Render Leaf Lard

Unlike bacon drippings, good-quality lard doesn’t taste anything like pork. Lard can be used for deep frying, but it can also be used in pies, biscuits, cookies, and scones.

Traditionally, leaf lard was reserved for making the very best pies. Leaf lard is taken from the leaf fat, which is a lobe of fat found near the kidneys.

It’s roughly shaped like a leaf, thus the name. Since the leaf fat is softer, the lard is spreadable at room temperature, making it very easy to work with.

Regardless of the fat you choose, it will render cleaner if you grind it first.

The more surface area, the easier it is for the fat to melt without taking on any extra porky flavor.

Lard can be made from any pork fat, but backfat lard will be harder in texture and is better for deep frying.

Save the back fat for use diced up in cured sausages or cured as lardo, and make your lard from leaf lard if you can.

How to Cure Cure Pork Back Fat

Back fat is a solid sheet of fat above the pork loin and just under the skin. In heritage breeds, it’s often several inches thick. To make quality lardo, the backfat needs to be at least an inch thick.

In today’s lean pigs, it’s rarely enough to cure on its own. If you want to make quality lardo or any sausage containing back fat cubes, raise a traditional heritage breed. Our home-raised heritage pigs had nearly 2 inches of backfat at 5 months old, so no problem there.

Lardo is cured back fat, which is sliced paper-thin. It has a silky texture and complex flavor that’s developed in 3 to 6 months of curing. The author of The River Cottage Curing and Smoking Handbook gives this suggestion for the best way to eat lardo:

“[Lardo should be] sliced gossamer-thin and can be eaten raw with a small amount of olive oil, or as I particularly recommend, wrapped around freshly steamed asparagus so that it becomes translucent and melting.”

Lardo is also made into a dish called Pesto Modenese, which is lardo whipped with parmesan, garlic, and herbs. It’s used as a rich spread on bread or toast.

- Bacon is Magic – How to Make Lardo

- Bacon is Magic – Pesto Modenese (whipped lardo spread)

- Hunter Angler Gardener Cook – Lardo, or Cured Italian Pork Fat

How to Use Caul Fat

Caul fat is another type of fat that surrounds the intestines like a lacy membrane. This very particular type of fat is used to wrap meatballs, sausages and specialty items.

Historically, the butcher would keep this type of fat as an extra and use it on his own table. These days, it’s finding its way into high-end restaurants.

If you want to see true beauty, check out these pork liver and caul fat caillettes. Trust me. It’s hard to make liver and caul fat sexy, but these are about as sexy as nose-to-tail eating gets.

Traditional “Butchers Faggots” are a dish made by British butchers to use up the truly odd portions of the pig that are hard to sell. Things like lungs and caul fat go into this delicacy, that was reserved especially for the butcher’s family. Scott Rea has a video recipe for butchers faggots that takes you through the whole process:

Preserving Pork Bones as Stock

The bones are full of nutrient-rich marrow and cook down into a delicious and protein-rich bone broth. A single pig yields a lot of bones, which means a lot of pork stock.

A single pig will yield between 40 and 60 quarts of pork stock, and though it can be frozen, that’s a lot of freezer space and electricity.

A better method is pressure canning.

We also incorporate the organ meats into stock, which adds more flavor and richness.

Final Thoughts

Keep in mind that all of these cured meats will need space to cure, sometimes for a year or more. While a back closet is great for the occasional dry-cured cut, a whole pig is going to need ample space and good airflow. Do you have enough space on hand to accommodate a whole pig dry curing?

Perhaps before you commit to a whole pig, consider portioning off a portion of your basement as a root cellar. Better yet, build one outdoors.

My friend Teri at Homestead Honey has an e-book on building a homestead root cellar, and it’s an amazing resource that talks you through the whole process step by step.

What are your favorite ways to preserve pork? What methods have I missed?

I’d love to hear your ideas in the comments below.

More Traditional Food Preservation Guides

Looking for more ways to put up the harvest? Read on…

- Preserving Cheese in Wood Ash

- Lacto-Fermented Pickles

- Farmhouse Cheddar ~ 18th Century Recipe

- Salt Preserved Lemons

- Salt Cured Duck Breast

There’s another method that I never see mentioned, but was widely used. Pork would be cooked (either cuts of meat or as sausage patties), then placed in a crock and covered with fat from the pan. The crock would eventually be full and topped off with fat, which would harden as it cooled. Throughout the winter, meat would be removed and reheated, and additional fat could be poured over to reseal.

I’ve seen this mentioned three places:

– a long list forum thread about life growing up in Manitoba in the mid-century. Most of the people were kids in the 1940-50s

– I believe this is mentioned in one of the Laura Ingalls Wilder books, maybe Big Woods

– my great-grandfather wrote a memoir about growing up on a farm in central Missouri and he mentions this technique and describes the sausage as being the best he ate

This is essentially the same technique as duck confit. It seems like it could have advantages in some circumstances, since there’s no lengthy salting or drying time involved.

Hi amazing article, thank you for sharing. You might want to. look into the Romanian kitchen recipes for how to preserve a entire pig, we used to cut a pig for Christmas and every bit of meat was used.

If you need any help with the translation send me an email.

Thank you.

Excellent post! Although it’s not something that can be preserved (that I know of),I would like to mention 2 more uses of pork. One is the brains and the other is the “scrap”. In rural eastern NC brains and eggs are a common and well liked breakfast. Never had them but know people who grew up eating them and loved them. I believe they were scrambled together with the eggs. In Delaware, the “scrap” (lips, nose, etc) is ground up with added spices and made into a brick called scrapple. It is sliced and fried like sausage. Never had it but people up there love it.

I’d also like the second comment made earlier about smoking. Post oak is exactly what was used. My rural east TX swore by it.

Hope that helps!

PS Can you share his recipes??

Thanks so much for sharing. We’re glad you enjoyed the post.

I open-kettle can lard and then store it in my cellar. Like that it lasts for years in pristine condition. Properly rendering the lard before canning is critical of course.

I love this information. Is there anyway I can obtain a hard copy?

I’ve been looking at putting it all out in printable pdf format, hopefully sometime this year.

How long does pork lard last. I made lard for the first time a few years ago but gave most of it away as I could not really find conclusive data on how long it lasts. I did put some in the freezer and that seemed OK. What are your thoughts?

Properly rendered lard should be shelf-stable for years…in theory. Sometimes, as with any oil, the flavor goes off and it goes rancid. It’s not “spoiled” technically, it just tastes horrible. Some people keep it in jars in the freezer to extend shelf life and prevent it from going rancid for longer. Historically, it would have been kept in the root cellar just to keep it cool. (Improperly rendered lard that still has water in it, or other impurities, can spoil, so be careful about that.)

What an innovative & smart idea this is!!! Never think about this really before reading your article. So much helpful & valuable for me. Thank u so much for sharing this wonderful article.

This is a great article and if you are doing this for great food then this would be great, but for survival I do not think you would have enough time to do all of these so below is what my folks did back in Tenn.

My Dad, uncles, Grandfather prepared a hog was either to sugar cure , smoke or salt cure all of it. From my understanding any of these methods will cure all of the hog. But it has to be done right. The meat if sugar or salt cured has to be turned often or else not all the blood will drain out away from the bone. The bone or middle area of the meat like a ham is the problem area. you Have to get this area cured and that takes time, turning and rubbing the cure every time it is turned. A lot of work to be sure. Smoking is just as bad lol the meat has to be kept at a certain temperature for a long period thus a smoke house was used with a smoldering fire that allowed the heat and smoke to go through the smoke house. This fire had to be kept going the full smoking time. I do not remember how long but have it written down somewhere lol.

Sounds so good. Wish I could partake, but I developed a pork allergy when I got into my 20’s. Enjoy some for me. 😛

Oh man, that’s horrible! I’m sorry about your allergy, but keep in mind many of these could be made with beef too =)

I have a bunch of bacon recipes from the old days when I used to eat pork.

If your interested anyway?

I do commercial curing bacon sausages etc or should I say custom curing and bbq.

I cook about 500 pigs or process that many yearly easily for custom feed for families around my home. This is my full time job having a German wife the stuff comes pretty naturally.

We make a bacon called Kennedy bacon the recipe is from Kennedy texas it’s probably the best bacon I ever ate the smoke on it like central Texas bbq is all oak wood called post oak. It’s probably my favorite bacon I ever ate when I used to partake of the swine regularly.

The curing spices and wood make all the difference in the world. Best bbq smoke is here so why shouldn’t best curing wood be the same right. It is actually after trying every wood I could order online Apple to anything else this simple post oak gives the best flavor of any wood out there second is probably mesquite smoked bacon followed by apple I like or any fruit wood.

Y’all enjoy if you want me to email you recipes be happy to lady writer sorry just happened across this don’t know your name yet.

That’s wonderful! I’d love to hear your recipes. I’d post them too, if you’d like (with a credit to you of course). You can email them to Ashley.Adamant@gmail.com

Very thorough post about preserving a whole pig. One little note – “Canadian bacon” is only called that outside of Canada. Here, we call it Back Bacon. It cures in about a week, so it’s a short-term way to store the delicious loin while you’re getting the rest of the pig processed.

Thanks, Marie! It makes a lot of sense that Canadian’s wouldn’t call it canadian bacon…Thanks for sharing!

What a comprehensive list of ways to preserve pork! It is the only reason I could never be vegetarian! Thanks for linking to my pancetta recipe! 🙂