Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Pin cherry (Prunus pensylvanica) is a wild shrub or small tree that grows wild across Canada, North Central and the Northeastern US. Related to chokecherry and black cherry, the small red cherry fruits on this species can be easily identified by their unique growth pattern.

Pin cherries (Prunus pensylvanica) are a true summer treasure, especially for those willing to venture a bit off the beaten path. These bright red fruits aren’t something you’ll find at the farmers market—they’re a forager’s reward. Though tiny, they’re incredibly popular with foragers, who love to make them into jelly and syrup.

The trees are prolific, and though they are small (thus the name), it’s easy to collect them by the bucketful.

Since the trees are fast growing, harvests increase every single year. They produce at just 2-3 years old, and are full grown trees by 8 to 10 years old, much faster than most cultivated trees.

And the birds appreciate their fruit, spreading them further each year.

What are Pin Cherries?

Pin cherries (Prunus pensylvanica), also known as bird cherries or fire cherries, are small native trees or large shrubs found across much of North America. They are typically early colonizers after disturbances like fires or logging, hence the nickname “fire cherry.”

Pin cherries are deciduous perennials, quickly establishing themselves in sunny, open spaces before giving way to slower-growing species.

Are Pin Cherries Edible?

Yes, pin cherries are edible, although they are very tart and have a relatively large pit compared to their flesh. They are best cooked into jellies, syrups, or wine rather than eaten fresh. The fruits are quite sour raw, but cooking balances their flavor beautifully.

As with all stone fruits, the pits contain compounds that can release cyanide if crushed, so they should not be consumed.

Pin Cherry Medicinal Benefits

Native American tribes traditionally used pin cherries for both food and medicine. Decoctions of the bark were used to treat coughs, fevers, and digestive issues.

Modern studies of Prunus species suggest that they contain antioxidant flavonoids and phenolic compounds that may have anti-inflammatory effects.

In general, their medicinal benefits are similar to other closely related species, including wild black cherry (Prunus serotina) and chokecherry (Prunus virginiana).

Where to Find Pin Cherries

Pin cherries are found across much of Canada and the northern United States, stretching from New England and the Great Lakes region across to the Rockies and into parts of the Pacific Northwest. They prefer disturbed soils, sunny slopes, forest edges, and old fields. You’re most likely to find them growing in open, sunny areas where competition from larger trees is limited.

The trees are a pioneer species, often growing in recently cleared land, or just about anywhere they can gain a foothold. They’re commonly found in abandoned gravel pits and abandoned fields. They prefer dry, sandy or gravelly soil, which happens to perfectly describe where we found them.

Pin cherries grow very quickly, and they can go from seedling to bearing age in just a few years. When we cleared a patch of land three years ago the soil was bare, no cherries insight.

Three years later the biggest pin cherry is nearly 10 feet tall, and many others are 5-6 feet tall. Generally, they don’t fruit until they’re 12 to 30 feet tall and the trunk is 2 to 6 inches in diameter so ours are a bit ahead of schedule.

Though pin cherries colonize and grow quickly, they’re a short-lived tree. Once other trees begin to take root, pin cherries will die out as the canopy fills in. Pin cherry trees tend to grow in colonies, and ours are in a colony of nearly a dozen individual trees growing right up against a pair of mature sugar maples.

When to Find Pin Cherries

Pin cherries bloom in late spring, typically around May to June depending on latitude. Fruits ripen in mid to late summer, usually between July and early August.

In warmer areas, the season starts a bit earlier; in colder climates, the fruits may not fully ripen until later in August.

Identifying Pin Cherries

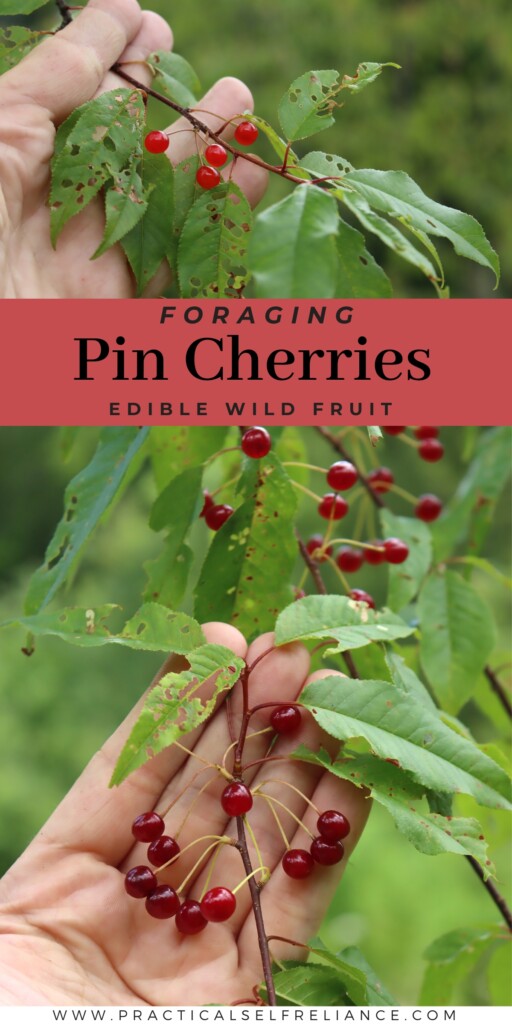

Pin cherry trees are slender and small, usually no more than 30 feet tall, and often much shorter. They grow with a graceful, somewhat sparse crown and have thin, smooth reddish-brown bark that sometimes peels slightly with age. The clusters of small red cherries and narrow leaves make them easy to recognize once you’re familiar with them.

Pin Cherry Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and lance-shaped—long and narrow compared to most other cherries. They have finely serrated edges and are 1 1/2 to 3 inches long, occasionally stretching as long as 5 inches on some trees. The leaves are bright green above and paler underneath.

Overall they look much like many other stone fruit species.

Pin Cherry Stems

Young branches are slender and reddish, becoming grayish as they age.

The bark on cherry trees is very distinctive, and that’s how I knew they were a cherry species from a very young age. It has a reddish-brown hue, and small horizontal white or tan lines. Other than the lenticels, the bark is very smooth and thin.

As they grow older, the bark may begin to peel in papery sheets a bit like birch bark.

Pin Cherry Flowers

Flowers appear in loose clusters of five to seven blossoms. Each flower has five white petals and a prominent center of yellow stamens.

Blooming usually occurs before the leaves are fully matured in spring.

Pin Cherry Fruit

The fruits are small, about 1/4 to 1/3 inch across, and brilliant red when ripe. Each cherry has a thin layer of tart flesh surrounding a relatively large pit. They grow in loose clusters and are a favorite of birds, hence the nickname “bird cherry.”

Though the fruit are small, the trees can bear heavily. The fact that the trees often grow in colonies also helps bring in a bigger foraged harvest. Even with heavy yields, it’s often hard to pick a substantial amount.

As the fruit begins to ripen, they’ll turn a deep purple on one side before they fully ripen to a bright red, glossy color.

I’ve read that the fruit are occasionally orange or yellow-colored on individual trees, but that’s a relatively rare mutation.

Pin Cherry Look-Alikes

Wild pin cherries look quite a bit like chokecherry and black cherry, at least before they flower and fruit. Once they begin to flower, the flower clusters are quite different, and the fruits are born individually instead of in racemes.

- Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana): Chokecherry trees produce denser fruit clusters, have broader leaves, and the fruits are slightly larger and darker when ripe.

- Black Cherry (Prunus serotina): Black cherry fruits turn black when ripe and the leaves have a waxier feel with fine teeth along the edges.

- Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis): Hackberries can sometimes confuse foragers due to their small fruits, but they grow on different tree types with rough bark and edible crunchy seeds inside.

- Wild Plums (Prunus spp.): Wild plums produce larger fruits that vary in color and flavor but tend to grow on sturdier trees with broader leaves.

Pin cherries are quite similar to cultivated pie cherries (sour cherries) except that they’re much smaller. Much like any other type of cherry, the fruits often come in groups of two.

How to Process Pin Cherry Fruit

As the name suggests, the fruit of a pin cherry tree is very small. The very small fruit has very little actual cherry meat since the seed inside is so large. There’s barely a millimeter of flesh around a large white seed.

It’s impossible to pit a pin cherry, as anything that could puncture through the outside and drive the large pit out would also pulverize the thin coating of flesh.

The flesh can be removed by simmering in a tiny amount of water, or by a food mill. The author of The Forager’s Harvest says that they make “one of the best jams ever tasted.”

He suggests using a food strainer with the tension spring removed to separate the pulp from the seeds for jam making. Our young trees didn’t produce a jams worth this year, and all the cherries were eaten out of hand.

Ways to Use Pin Cherries

Pin cherries are best suited for making jelly, syrup, wine, and vinegar infusions. Their tart flavor shines when sweetened and concentrated. While you can eat them fresh, most people find them too sour without processing. My family tends to enjoy sour fruit, so we like them just as they are.

Historically, pin cherries were dried into cakes by Indigenous groups for winter use, similar to traditional dried chokecherry patties, and the bark was valued for its medicinal properties.

My personal favorite is pin cherry jelly, which comes together quickly and is easy to can so I can enjoy it anytime.

How do Pin Cherries Taste?

I’ve read that they can vary greatly in taste and that some wild trees have cherries that are bitter and sulfurous. Others taste much like cultivated sour cherries, only a bit tarter.

The pin cherries on our tree were sweet, mildly astringent and pleasant with just enough tart to make things interesting.

It’s hard to get much flavor off of them fresh since there’s so little cherry flesh. Just the tiniest hint of sweet, with a mild cherry taste and a bit of mild bitterness.

My 18-month-old foraging buddy saw mama harvesting and he had to get in on the action. He dropped his bottle and spent about half an hour carefully hunting berries and popping them into his mouth with delight.

There you have it, they’re bottle-dropping good to a toddler.

The seeds are so small that they’re no bigger than the seed inside an old-fashioned seeded grape, which means they’re no big deal if a child eats a few here or there. They come out the other end in much the same shape they went in.

I’m always impressed at how much my little ones remember when we’re out foraging. This little guy still runs over to the pineapple weed patch with glee, and if I say black raspberries he’ll be across the yard to the edge of the woods in a second.

I always watch him as he’s harvesting, and his tiny hands know just how to avoid the thorns in our wild raspberry patch. Some of the black raspberries grow right up among mildly toxic invasive bush honeysuckle plants, yet he’s never picked them.

The berries look a lot like pin cherries, but I’ve never shown them to him so he doesn’t eat them. I wonder if that’s because my kids have grown up following mama around foraging?

As soon as my daughter had words she’d ask time and time again, “Is this an eating flower mama?” Pointing to jewelweed, red clover or some other common wild blossom.

She asked about the bush honeysuckle berries once, and I explained that they weren’t good to eat and the plants grew them just for the birds. Even now, years later she still will try to get the bird’s attention in the yard and call them over to eat their bird berries when the bushes are overflowing with fruit.

We’re a hunter-gatherer species, and foraging is in our blood. All it takes is a little time to rekindle that fire, and kids can memorize wild edible plants after one or two mentions once foraging becomes part of their daily lives.

Pin cherries are now part of my 1.5-year-old and 3-year old’s vocabulary, and they’ll be waiting for them with excitement next year.

Edible Wild Fruit

If you’re out gathering pin cherries, you’re likely to find other wild fruits ripening around the same time. Wild strawberries grow low to the ground in sunny clearings earlier in the summer, offering sweet, tiny fruits packed with flavor. A little later, wild black raspberries start coming in, dotting field edges and woodland trails with rich, dark berries perfect for fresh eating or jam.

In moist soils and along riverbanks, northern dewberries sprawl across the ground, producing juicy, blackberry-like fruits that ripen mid to late summer. Meanwhile, hawthorns begin to bear their distinctive small, apple-like fruits, which can be foraged into jellies or dried for winter teas.

If you’re lucky, you might also come across wild gooseberries growing in partial shade. Their tart berries are excellent for cooking into pies, sauces, and preserves. And later in the season, keep an eye out for rowanberries, whose bright orange-red clusters are a beautiful and useful late-summer wild harvest.

Thanks for the great content! I think I have a pin cherry tree in my backyard… however the blossoms are really deep pink in the spring, not white. There are so many blossoms that the bees go crazy — the tree is literally BUZZING. You can hear it from quite a distance. 😉 Anyway, I am wondering if it is the same kind of tree you are describing here. Would love to make jam if it is. There is so much fruit!

If the blossoms are pink and not white, it sounds like you have a different tree. Depending on the variety, it may still be edible though.

Wonderful post–very informative and encouraging. Thanks Ashley!

You’re very welcome. So glad you enjoyed the post.

Great read! Thanks. And wonderful job raising the offspring to know the natural world 🙂

Thank you!

Love your posts Ashley. Very informative. Ty Frank Hykes