Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

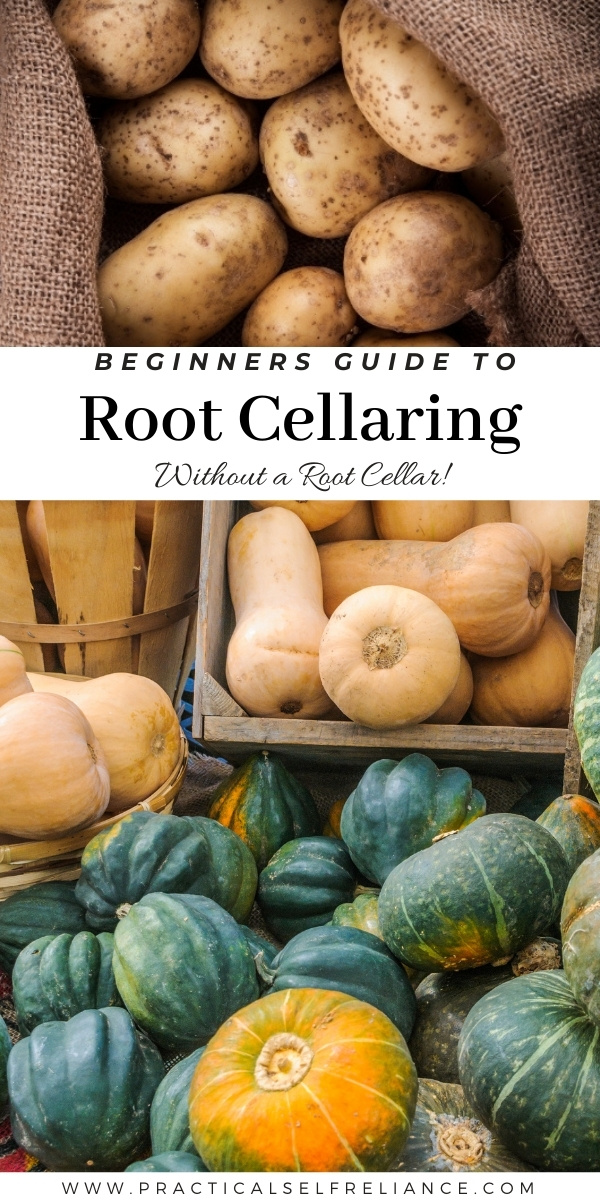

What is a Root Cellar?

Root cellars are storage locations that are typically built underground or partially underground. Root cellars make use of the earth’s natural cooling and insulating properties, in addition to steady humidity levels, to create a stable storage environment.

They’re used to store and extend the shelf life of fruits and vegetables, canned and pickled foods, perennial bulbs or rhizomes, cured meats, cheese, and homemade wine, beer, or mead.

Before the invention of modern refrigeration, root cellars were commonly used in many parts of the United States to store food. When English settlers arrived they had to contend with a new, more humid, climate that wasn’t conducive to long-term food storage.

According to Dusty Old Thing’s essay on the history of root cellars:

“Root cellars were not a hugely common feature of many houses in England, so when the settlers came to the Americas they discovered they needed to be much more proactive about their food storage in the more-humid climes they now called home. Colonial New England homes were often outfitted with storage space below ground, and the tradition became common across the country by the time of Westward expansion in the 1800s.”

Nowadays, with almost every household in possession of a fridge, the main reasons for root cellaring are often centered around sustainability and reducing food waste.

Beyond that, maintaining a root cellar is very low cost, in terms of both financial and energy expenditure.

We don’t have anything fancy, just a part of our basement that we keep segregated from the rest. It’s not ideal and ranges between 45 and 55 degrees during the winter months, but it still works wonderfully to store just about all our produce for the winter.

It’s a work in progress, but we’ve been able to overwinter roughly 200 pounds of each potatoes, onions and apples (600 pounds total).

Plus, roughly 100 pounds of pumpkins and squash, Brussel sprouts and cabbage, as well as 40 to 50 pounds of homemade cheese and cured meats.

Basic root cellar requirements

When designing your own do-it-yourself root cellar, there are a few important elements to be considered.

Temperature

Ideally, a root cellar should be between 32° and 40° F — close to freezing but not quite. The colder the root cellar, the longer its contents will keep.

My root cellar runs warm, at around 50° F, but still does a good job at keeping things fresh throughout the winter.

Ventilation

Proper ventilation is key, as it decreases the likelihood of mold and prevents ethylene gas, a gas emitted from certain fruits and vegetables, from stagnating and causing other types of nearby produce to ripen and spoil.

Sheltered Location

Traditional root cellars are built underground for a reason! The surrounding soil passively works to insulate the cellar, while also helping to regulate temperature and humidity levels.

You can simulate this by with straw bales if an actual underground earth sheltered location isn’t an option, or by using repurposed insulated storage…anything from an old ice chest to a busted refrigerator or just plain old scraps of blue board insulation.

Humidity

Your desired humidity level will depend on what you plan on storing in your root cellar, but it should fall within the range of 85 to 95 percent.

(Onions like less humidity, apples like as much as possible. Scroll to the end of the article for specific requirements.)

Using dirt and gravel for the flooring will help regulate humidity levels and allow for proper drainage.

Darkness

Light will drastically shorten the shelf life of any items stored in your root cellar. If you have windows where light is seeping in, seal them off from sunlight completely!

Accessibility and Storage Containers

Build your root cellar in a location that’s easy to get to (think about how cold and snowy it can get in the winter, for example, if the cellar is not attached to your house).

Untreated wooden shelving and wooden boxes are ideal for food storage as they have natural antimicrobial and antibacterial properties.

DIY Root Cellar Ideas

For most modern homes, a traditional root cellar isn’t exactly practical (especially in an apartment or the suburbs). That doesn’t mean you can’t “root cellar” food using whatever space you have available.

I’m going to walk you through some of my favorite ideas for creating a cellar-like space in unique settings.

Backyard root cellars

If lack of space is all that stands between you and a root cellar, you might want to consider building a root cellar in your backyard using a large bucket, barrel, or garbage pail (and in some cases, an old freezer!).

These backyard cellars all share the same premise: they’re dug into the soil, filled with fruits and vegetables, covered with a lid, and then — especially in warmer climates — they’re covered with straw to further insulate and protect the contents of the makeshift cellar.

Indoor root cellars

Closets that are on the exterior of a house (or any consistently chilly closet space) can be used as DIY root cellars for certain types of hardy fruits and vegetables.

In fact, any part of your home, such as the basement, a crawl space, or under the stairs, has the potential to be used for food storage as long as the temperature and humidity are constant and the light is kept to an absolute minimum.

I’m still in the planning stages of our outdoor root cellar, so we currently use our basement to store food over the winter.

For more information on building a basement root cellar, this in-depth article goes into the nitty-gritty details of planning and putting together a basement cold-storage area.

Earth pit root cellar

An earth pit root cellar is about as simple as it gets when it comes to root cellar-adjacent methods of food storage. A large hole is dug in a well-drained, shady spot and the base of the hole is filled with sand or sawdust.

The hole is then filled with root vegetables (potatoes are particularly well-suited to this type of cold storage) and then topped with more sand or sawdust plus a generous layer of leaves and straw. The hole should be covered with a weighted-down tarp to protect from the elements, hungry animals, and to help further insulate the cellar.

Heeling In Vegetables

If you’re really short on space, you can “root cellar” right in the garden using a process known as “heeling in.” Vegetables are stored in shallow trenches in the soil, surrounded by and buried under straw. This guide walks you through the basics.

(You can also just store root vegetables by leaving them in the garden. This works especially well for carrots and parsnips, which get sweeter when exposed to frost. We’re able to dig them every month or so as we get periodic thaws, even here in zone 4 Vermont where we see -25 F in the winter.)

Types of root vegetable environments

There are two main types of root vegetable environments, cool and damp (32° to 40° F with 90 to 95 percent humidity) or cool and dry (50° to 60° F with 60 to 70 percent humidity).

In an ideal world, you’d have two different root cellar spaces, one for cool dry, and another for cold/wet storage. Practically, that’s rarely an option, and just about everything we store is in a cool dry basement (45-55 degrees, and 70% humidity) by simply creating a “humid microclimate” section for moisture-loving crops using passive methods.

Crops to store in a cool and damp root cellar

For moisture-loving crops, you can create “micro-climates” within a root cellar to help them store better. We wrap each apple in newspaper, which helps maintain moisture.

Carrots and other root crops are burried in moist sand within the root cellar.

Apples

For optimal storage and longevity, store newer apple varieties in a cool and damp root cellar. Tart, crisp apples generally keep longer than sweet, softer apples, but I’d suggest looking through this list of the best storage apple varieties to help ensure success.

For best results, wrap apples individually in newspaper and store in cardboard boxes or wooden crates. Storage apples have a shelf life of 2 to 7 months, depending on the variety.

(Not all apples are “storage” varieties!)

Pears

Select unblemished fruit for overwinter storage as pears are very delicate and keep them stored at a cool 29° to 31° F. Pears should be individually wrapped in paper and carefully stored in cardboard or wooden boxes lined in perforated plastic. Prepped for long-term storage with care, pears will last from 2 to 3 months.

They should be harvested slightly underripe, and even then, this will only work with storage varieties. Bartlett is a good example.

Root Crops ~ Beets, Carrots, Parsnips, etc

Remove the green tops from beets before placing them in damp sand, peat moss, or sawdust — store beets apart from one another in a lidded plastic container or a wooden box.

Alternately, most types of root vegetable can be stored in the garden over the winter, as long as you don’t have issues with rodents and can cover them with 1 to 2 feet of hay or straw.

Most root crops will keep 2-6 months, depending on the variety and conditions.

Broccoli, Brussels Sprouts & Cabbage

Members of the Brassica family keep well in a cool and damp environment. Broccoli, the most delicate of the group, should be stored in a perforated bag away from ethylene gas-producing fruits or vegetables and will keep 1 to 2 weeks.

For the sweetest Brussels sprouts, harvest them after repeated exposure to frost (or, if possible, pot the plants and bring them inside to keep in the cellar over the winter); harvested sprouts will keep for 3 to 5 weeks.

Alternately, dig up whole plants and move them to the root cellar in buckets. Keep the roots just barely moist, and the sprouts will store on the plant for a few months.

Keep cabbage in an outdoor cold-storage container unless you want their sulfurous smell having an effect on the rest of your stored food — you can also wrap them individually and store them spaced apart.

Whichever method you choose, cabbage has a shelf life of 3 to 4 months.

Potatoes

Potatoes should first be allowed to cure at 45° to 60° F for 10 to 14 days, after which they should be stored at 40° to 45° for the next 4 to 6 months.

Avoid storing potatoes with apples or any other ethylene producing crop to avoid sprouting.

(This past year, we planted four raised beds (4 x 8 ft) with potatoes and harvested well over 200 pounds of potatoes without fertilizer, weeding, or irrigation. That’ll take us through the whole winter, and I can’t think of an easier way to put away plenty of homegrown calories than growing potatoes.)

Crops to store in a cool and dry root cellar

A cool, dry root cellar is much easier to replicate at home than a moist location. A back closet works wonderfully, and even finished basements tend to stay cool enough (and dry enough) for these crops.

Garlic

Garlic truly prefers dry storage conditions, humidity causes undesirable mold growth and rot. Make sure your garlic has been completely cured before it’s transferred to the root cellar.

Once cured, remove the tops from hardneck garlic and store in a mech bag or, if you softneck garlic, it can be braided and hanged from the ceiling or a hook.

Depending on the variety, garlic can be stored from 5 to 8 months.

Onions

Remove the tops from cured onions and store in some kind of well-ventilated container, this could be a mesh bag, paper grocery bag, or you can try the pantyhose method.

Onions can be kept from 5 to 8 months, though some varieties will keep as long as a year in ideal conditions.

Pumpkins and Other Winter Squash

With the exception of acorn squash, all varieties of winter squash should be cured before long-term storage. Remove the stem — keeping about an inch or more still attached to prevent spoilage — and store for 4 to 6 months.

Beyond Root Cellaring Vegetables

Root cellars aren’t just for vegetables, they work well for homemade cheese and cured meats too. I have pancetta curing in my basement at the moment, and in the past, I’ve aged homemade cheddar right alongside my storage apples.

I’ve aged farmstead cheddar and Colby cheese in my basement successfully, as well as duck breast prosciutto and guanciale (jowl bacon), without any modifications to my otherwise less than ideal “root cellar.”

(These days, I make at least 10 pounds of cheese a month, and I’ve invested in a small wine cooler that I’ve modified and repurposed to be a cheese cave. That creates allows me to better control humidity, which is a problem in my basement as it tends to be a bit dry for aging cheese. Still, most homemade cheese is aged at 50 to 55 degrees F and around 85% humidity, so not all that different than apples.)

Food Preservation Methods

Looking for more ways to store the harvest?

- 30+ Ways to Preserve Apples

- 30+ Ways to Preserve Lemons

- 30+Ways to Preserve Eggs

- 20+ Ways to Preserve Pumpkin

Wow! The information you provide on a regular basis, is invaluable. I spend a lot of time reading and saving your posts. Thank you so much!

I’m so glad it’s helpful to you!

We in Flanders hung, cured and dried our meats above our crates of beer. The organisms around the beer affect the process of the drying, curing meats. Just as the exclusive organisms, only to be found in the Zenne river valley in Brussels create the unique Lambic beer. The same goes for all cheeses. All milk is different according to the environment and the process of its typical cheeses is always local. No use to try to make a roquefort in Danmark.

Molds and fungae are also good, and the process of the sugars and yeasts and others does its jobs. Sometimes it is also good that something rots once in a while 🙂

We have used many of these alternative methods and do fairly well with keeping a lot of food fresh through the winter. i much prefer to use fresh product than frozen, so whereever we can i store it fresh. thanks for more good ideas.

Wow! Good information. I just subscribed and I’m really excited to read more. Thank you so much.

Wonderful, so glad to have you along!

Although your article mentions rodents when storing roots in the garden, I find it safe to also keep root items in rodent proof enclosures in a root cellar. Controlling moisture and temperature can be difficult but feeding the local mouse population can ruin a crop. I’ve had good luck with wood boxes which will keep them out for a while but 1/4 inch hardware cloth is also a good way to keep mice out and provide some ventilation. If they can get in they will and making a traditional root cellar totally rodent proof can be difficult. I’ve also lost crops to inadequate ventilation and reading up on how to ventilate a space while keeping it cool but not freezing is a good idea.

Thank you for this article. Gave me hope for finding a way in my warmer rocky mini-farm.