Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

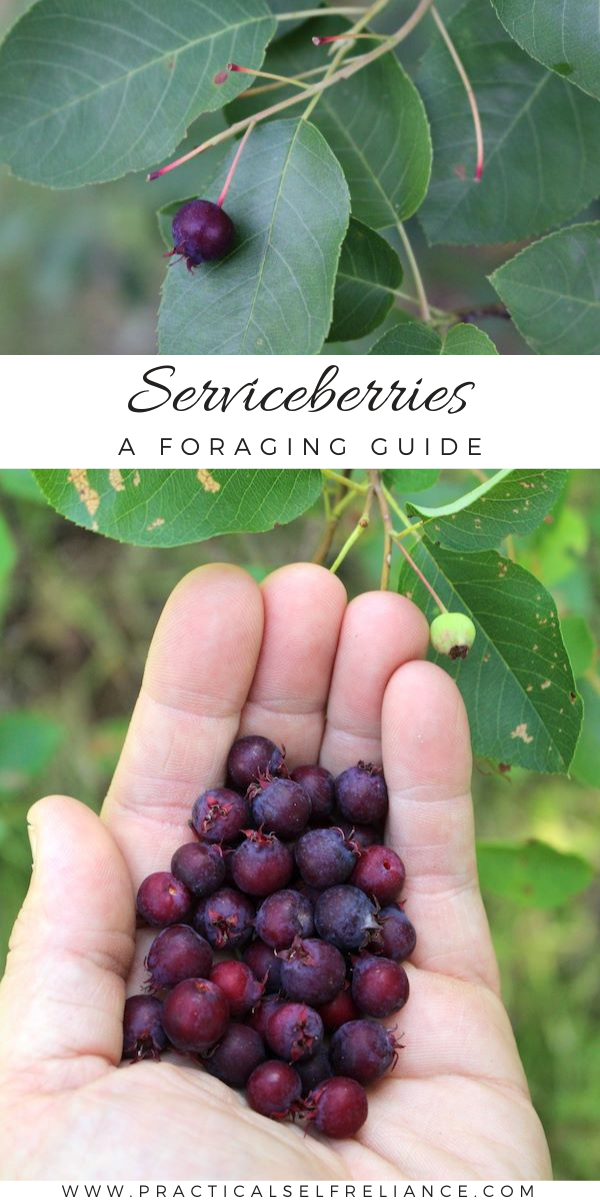

Serviceberries are a delicious blueberry like fruit that grow on the branches of Amelanchier trees and shrubs. Proving the old adage that a much-loved child has many names, serviceberries go by a number of other names including Saskatoon, Shadbush, Shadwood, Pidgeon Berry, Bilberry, Sarvisberry, Sarvis, Sugarplum and many others.

Truly ripe serviceberries are a real treat, and though I forage literally dozens of edible wild berries each summer, a perfectly ripe serviceberry puts them all to shame.

The trick is beating the Cedar Waxwings to the fruit, as they’re liable to pick them off at the first hint of pink, long before they ripen to a deep purple. In mast years, the fruit will overwhelm the birds, meaning you can pick them by the bucket load in the right spot.

The very best time to identify serviceberries is in the early spring, when their white blooms stick out against a still dull countryside. Serviceberry trees fill with small white blossoms just as the earliest trees are breaking bud. The leaves of serviceberry shrubs have a brown/red/orange tinge as they’re emerging, making it especially easy to see the bright white blossoms against the dark background.

Later in the season, the flavorful berries may hide in the dense foliage. One of my favorite summer walking spots is covered in serviceberry trees, but I’d never noticed them.

That is, until I took a walk there in the spring months. They can be hard to notice during the fruiting season, even for an experienced forager.

Types of Serviceberry (Amelanchier Species)

There are many different species of serviceberry or suskatoon, and with species mostly differentiated by region. The plants are slightly different, as are the fruit, but as a whole, they’re all pretty similar wild edible berries.

The classification of serviceberries is actually a bit confusing, and even botanists will disagree on exact species names. There’s a lot of overlap and interbreeding, along with variation within species. It’s really not important to identify the exact species, just rather look for the general characteristics of all Amelanchier species for tasty serviceberries.

There are dozens of botanically named species of edible Amelanchier, but here are some of the more common varieties:

- Amelanchier alnifolia ~ Known as Western Serviceberry, dwarf shadbush or pigeon berry. This species is present in the western and North Central US, as well as all of Canada. (Range Map Here)

- Amelanchier arborea ~ Common serviceberry or Downy Serviceberry, this species is present throughout the eastern half of the US and Canada, and it’s one we harvest here in Vermont. (Range Map Here)

- Amelanchier bartramiana ~ Common names include Mountain Shadbush/Serviceberry or Olblongfruit Serviceberry, which describes this species well. The fruits are a bit unique in that they’re oblong in shape, a bit like a very tiny pear. This species is found in the Northeastern US and Canada. (Range Map Here)

- Amelanchier canadensis ~ Known as Bilberry, chuckleberry, sugarplum, and Canadian serviceberry, this species is present all along the East Coast of North America from the deep south to northern Canada. (Range Map Here)

- Amelanchier humilis ~ Known as low shadbush, this species only gets about 4 feet tall and maintains a bushy habit. I’ve yet to find it in the wild, but we grow this one on our permaculture homestead. Native to North Central and Northeastern North America. (Range Map Here)

- Amelanchier laevis ~ Called smooth shadbush/serviceberry or Allegheny serviceberry, this species is native to the eastern US. (Range Map Here)

- Amelanchier sanguinea ~ Known as round leaf serviceberry, this species has a different leaf shape than most which makes it distinctive. Native to the Eastern US and Canada. (Range Map Here)

Beyond those found in the wild, serviceberries are often planted in ornamental plantings, especially in the Northeastern US. Their beautiful flowers in the spring mean they’re well appreciated by landscapers, and the birds largely harvest the delicious fruit. They’re a common sight in parking lot plantings around public buildings and grocery stores here in Vermont.

Serviceberries ripen to a deep purple/blue, but it’s hard to find them completely ripe in the wild. I often harvest them a bit pink, and they’re still exceptional.

Identifying Serviceberries

Serviceberry plants vary in size depending on location and species. Some are small bushes just a foot or two tall, while others are modest trees reaching 30 feet or more. Either way, they tend to have a bushy habit, and even the taller tree serviceberries often have multiple small trunks.

The bark can be a nondescript grey color, but it often has subtle vertical striping. To my eye, it looks like stretch marks (but I’m a mother of two, so I’m pretty familiar with what those look like). On some trunks, they’re much more distinctive than others, with the “stripes” being a greenish color.

This is the easiest way to identify them out of season, and I’ll keep an eye out for their “stretch mark” bark alongside winter snowshoe trails.

Once spring arrives here in the north country, serviceberries are a lot easier to spot. They’re covered in distinctive white flowers, with 5 long narrow petals each.

On hillsides with multiple trees you can spot them at a distance, and it’s easy to mark dense patches of them (even driving at highway speeds). Flowering time varies by location, but it generally corresponds with the first warm spring weather.

The timing of the bloom gave rise to a legend about their name “serviceberries,” because they flower just as the soil has fully thawed. Historically, this meant that funeral services could be held and those that passed in the winter could be buried. In truth though, the ground actually thaws a month or more before they bloom, and if you had a corpse in the cellar you’d want it to be buried long before the weather became warm enough for serviceberries.

(The name actually comes from a mispronunciation of an older name given to the shrubs: sarvissberry.)

Either way, in Vermont they bloom in early May, just before the first dandelion blossoms, but the bloom is clearly much earlier in southern states.

The leaves of serviceberry trees change color throughout the season, and they start off with a rusty tinge. That dark brown/red color is a good backdrop for the bright white petals and makes it easier to spot serviceberry shrubs.

They lose that coloration as they mature into full leaves.

Full-sized serviceberry leaves are dark green with serrated margins, and vary a bit in shape from round to elliptic and ovate depending on the species.

I often find young plants growing at the edge of our woods, under trees where birds have dropped their fruit. Though the young plants are only a few inches high, I think the leaves are rather distinctive compared to most of the forest edge plants that grow in these parts. When I spot one, I’ll mark it with a quick tie of flagging tape and make sure to step around it and allow it to mature.

After the bright white flowers come green immature fruit. In some areas, the fruit ripen completely in June, before the summer solstice. That’s mostly the mid-Atlantic and southern varieties.

Up here in Vermont here’s what the young berries look like on summer solstice…

Sometimes, in warm years and with earlier varieties, they’ll be a bit further along. They may have turned pink in June, and be soft and sweet enough to eat.

Really though, while they’re tasty in this pink under-ripe stage, northern “Juneberries” don’t ripen until the last few days of June and into early July. The season peaks in July and August, as individual trees ripen at different rates.

Harvesting Serviceberries

When ripe, serviceberries look a lot like blueberries on trees. The blossom end is slightly different, and they have a deeper purple color than blueberries.

The fully ripe fruit is very soft and has multiple small seeds. I’ve read that some people dislike the seeds, and say that they have a mild almond extract flavor, but I barely notice them.

To me, they’re only slightly larger than blueberry seeds and they get lost in the small rich fruit. That may just be the varieties we have locally, and they may be more distinct elsewhere.

I often pick serviceberries a bit pink, since that’s the best way to beat the birds to them.

Serviceberry Recipes

For the most part, any recipe that calls for blueberries can be made with serviceberries. The fruit has a more intense flavor, that’s a bit like a blueberry on steroids. It’s honestly hard to describe until you’ve tasted one, but I think they’re one of the very best tasting (if not the best tasting) wild berries.

Here are a few recipes specifically developed for using serviceberries:

- Serviceberry Pie ~ The Kitchen Magpie

- Serviceberry Skillet Cobbler ~ Garden & Gun

- Serviceberry Jam ~ The Kitchen Magpie

- Gin Fizz with Serviceberry Syrup ~ Inspired by the Seasons

- Fermented Serviceberry Syrup ~ Edible Ohio Valley

- Serviceberry Muffins ~ Persephone’s Kitchen

- Serviceberry Ice Cream ~ Explore Big Sky

Honestly, I eat them as fast as I harvest them, so I’ve yet to cook with them. I’m out there, snacking up a storm in with plenty of cedar waxwings for good company.

Sam Thayer, one of my favorite foraging authors, harvests them in great quantity. In his book The Forager’s Harvest, he suggests the following:

“I store a lot of serviceberries and eat them year-round. If the weather is sunny, I sun-dry them; if it’s cloudy, I can them…Dried serviceberries are absolutely wonderful, and I most commonly eat them alone as a snack. I often bring a small bag of them with me on day trips into the woods. Mixed with hickory nuts they make a fulfilling, all-wild trail mix that seems too good to be true. the canned berries I spread on toast or acorn bread, mix with hot cereal, pour over pancakes or cornbread, or just dump into a bowl and eat as dessert.”

More Wild Edible Fruit & Berry Foraging Guides

Looking for more tasty wild edible fruit this season?

- Foraging Chokecherries

- Foraging Aronia Berries

- Foraging Pin Cherries

- Foraging Wild Plums

- Foraging Highbush Cranberry

- Foraging Nannyberry

Super helpful, Ashley, thank you! I just discovered we have the 30 ft understory variety of Serviceberry trees on our new land. I can order some more trees from our conservation department to plant and keep under cultivation closer to the house. I didn’t know that they were so tasty!

I know, right?!?! They are so darn good. Glad you found one =)

Hello. Love your posts and have learned so much, Thank you! Quite certain I have identified the fruiting shrub on our new property in the mountains of the northwest thanks to you. We’ve quite a few blue ones too. Yum!

Do you have a printed book you would recommend to help with edible plant identification? Love your blog but the cell reception and internet connection here are spotty and I need something printed that I can take in the woods with me.

Yes, you definitely want to invest in some good books. Here is a post with a huge list of helpful books. https://practicalselfreliance.com/books-for-self-reliant-living/ Sam Thayer is a great resource. He also has a new book that is not on this list which is his “Field Guide to Wild Edible Plants. It has a great key to help with identification and also tells you which parts of the plant to eat in which seasons. Botany in a day is also a really great resource that helps you learn how to identify plants through botany.

I have red glossy berries on stems with pointy green leaves along my drivewy/ I can’t tell what they are. Can you help identify them. Are they safe to eat ?

I would recommend getting a plant identification app or there is a plant identification group on Facebook that would be a good starting point. The apps can often be inaccurate though so be sure to just use this as a starting point and then do your own research to verify.

Hello, this is a great article. Can I ask you which one you prefer for eating purposes: A. humilis or A. sanguinea?

Thank you very much!

Both seem to have the same edibility rating from pfaf.org A. sanguinea is described as having a sweet flavor and A. humilis is described as “Sweet. Very pleasant flavour, the fruit is juicy with a hint of apple in the taste and contains a few small seeds in the centre.”

When I lived in Maine, the locals would note that the shad were flowering. As one of the names for them is ‘shadbush’. The reason I was told is that they typically flower when shad are running in the streams. So, their flowering is a marker of when to go fishing for shad!