Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Common Barberry (Berberis vulgaris) is an edible wild berry that’s common all over the world, and it’s even cultivated in many locations for it’s tart fruit. The fruit ripen in autumn, but they hang on the plants all winter long and can be harvested as late as spring or early summer.

Other species of barberry, including Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii) and American Barberry (Berberis canadensis) are also common as both native and invasive plants depending on the location, and they’re all edible. The fruit is what’s commonly used, but the foliage of barberry is also edible.

All parts of the plant are used in herbal medicine, especially the roots.

My family eats a lot of homemade international cuisine, and I’m a sucker for colorful cookbooks from around the globe. I was paging through one of my middle eastern cookbooks a few years back, and came across a full page spread of these particular, bright red clusters of oval berries.

I instantly recognized them as seemingly identical to a bush growing in our woods. I’d also seen it along roadsides and even used as a hedge in town. A little research and I learned that they are one and the same, common barberry (Berberis vulgaris).

How did this commonly cultivated edible berry from the middle east find it’s way to the woods of Vermont?

It turns out, it’s found its way to a lot of places, first as intentional ornamental plantings and then it’s spread by birds everywhere else. Though it’s a sought after part of the traditional cuisine in the middle east, it’s so common it’s actually considered an invasive species in many parts of the US.

Invasive doesn’t mean it’s not useful or tasty, it just means it grows prolifically and spreads so fast it out competes many other crops. That’s good news for foragers, because you can feel free to harvest as much as you want without impacting sensitive populations.

It’s rarely eaten in the US, simply because few people know it’s edible. Originally it came as an ornamental plant, like so many other invasive plants, and it does make an incredibly attractive hedge year round.

Though the clusters of bright red berries are stunning, and hold their color all winter long against the white snow, I’d guess they were actually originally planted for their showy clusters of fragrant blossoms.

In the springtime, the orchid like tropical smell of the blossoms travels quite a distance, and I can smell the blossoms on the bushes in our woods from at least 30 feet away.

Even if I couldn’t smell them, I could hear them….

They’re so popular with pollinators of all kinds that the bush actually “buzzes” as thousands of bees, butterflies and wasps work the tiny blossoms.

Identifying Barberry

Unlike many other edible wild berries, identifying barberry is actually quite simple because nothing else really looks at all like it. Except perhaps, other species of barberry, both native and invasive.

When in fruit, common barberry bushes are visible from a good ways off because they tend to bear so prolifically, and the fruits are bright red.

Since the bushes are quite tall, usually 5 to 12 feet in height, they can make a dramatic impression.

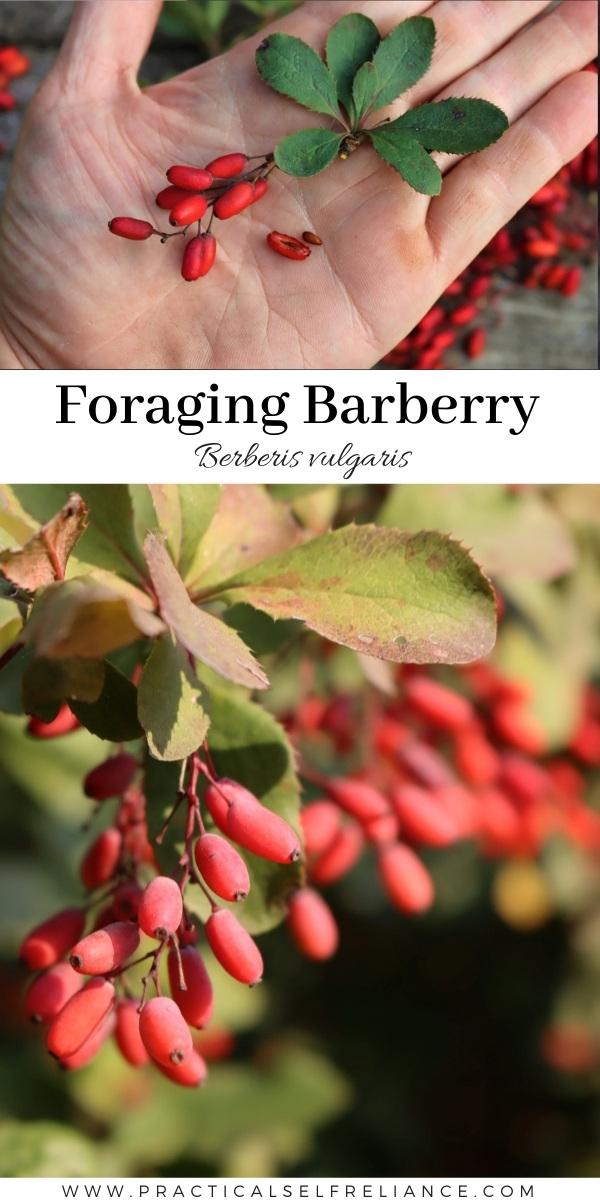

Up close, you’ll notice clusters of oblong red fruits, each hanging under a leaf node.

The fruits start to form after the yellow flowers are pollinated, and they’ll be green for most the summer.

In early autumn, they turn bright red and will hang on the plants for much of the winter.

Often they fully ripen after the birds have migrated for the year, like highbush cranberry and nannyberry, and they’re spread by the first returning birds in the spring (such as cedar waxwings here in the north).

The leaves of common barberry are roughly oval shaped, and with serrated edges.

They’re noticeable because they’re born in clusters along the branch, usually somewhere between 2 and 5 leaves together.

The leaves don’t actually come out of the branch itself, but instead they’re attached to a three pronged thorn/spike.

Incredibly sharp, these things are a real hazard when you’re harvesting barberry. The spines grow to about 1/2 an inch long, and since they’re 3 pointed they stick out in all directions from the leaf nodes.

Barberry fruits tend to dangle from the arching branches, and they’re often well below these spines.

If you’re careful (and don’t climb inside the bush), you can simply pluck the clusters off the undersides of the branches without going anywhere near these needle sharp spines.

Watch your clothes though, they’ll tear your shirt if you’re not careful, but that’s no different than foraging blackberries or hawthorn.

Barberry Look Alikes

The main look alikes for common barberry are other species of barberry, which also happen to be edible.

That said, I’ve seen people optimistically mis-identify things that really look absolutely nothing alike, hoping they’d found the plant they sought. There are other wild plants with red berries that are toxic, so be sure to look at plant carefully and make sure you do indeed have a barberry species.

Berberis canadensis

Berberis canadensis is an edible species of barberry that’s native to the East Coast of the US, but it only grows as far north as Pennsylvania. (Despite it’s common name that indicates it grows in Canada. Back in the day, when plants were first being named, growing anywhere on the east coast was liable get a plant called “canadensis,” as Canada wasn’t even a country at that point.)

It’s nearly identical to common barberry in appearance, and the only real distinguishing characteristic a layman would easily see is that the second year fruit baring branches are red/brown in canadensis, instead of grey in vulgaris. There are other really finicky differences, but you’ll have to get out a microscope and it’s hardly worth it unless you’re a botanist, since they’re both edible.

Japanese Barberry

Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii) is an invasive barberry species that’s just about everywhere, and if you’ve been hiking in semi-open woodlands it’s likely that you’ve caught your pant leg on it’s spines at some point.

The good news is Japanese Barberry is also edible, though not quite as tasty.

This species is quite similar to common barberry in many ways, but it’s easy enough to tell them apart, especially when in fruit or flower.

Japanese barberry doesn’t have clusters of red berries, instead the fruits grow singally from the underside of it’s arching stems.

The plants are low growing, usually only about 1-2 feet high, though I’ve seen them as tall as about 3 feet. Common barberry is much larger, reaching 12+ feet in height and it’s usually at least 4-5 feet tall when it starts fruiting.

My free range chickens are particularly fond of the Japanese barberry that grows at the edge of our woods, since they’re so low to the ground.

Popularity with birds helps to explain it’s prevalence, since it’s bird spread all over the world.

All species of barberry are incredibly popular with pollinators, and our native bumblebees have a particular passion for Japanese Barberry. They’ll hang on the undersides of the branches, walking along from flower to flower before moving onto the next stem.

These single flowers, like the single fruits, are a good indication you have Japanese barberry instead of common barberry which flowers and fruits in clusters.

The main thing I have noticed pollinator wise is that territorial wasps and hornets are incredibly fond of Japanese Barberry, and we tend to stay away from it when it’s in bloom.

Bald faced hornets, in particular, will defend Japanese barberry bushes and chase humans/animals/etc away during their 2 week bloom period. Every year I get chased by one when I happen to venture too close to Japanese barberry, and since they’re everywhere in our woods it can be a tricky time of year to take a walk.

Common barberry, however, doesn’t seem to hold the same attraction to wasps/hornets, and I’m able to enjoy its scent right alongside docile bumblebees in the spring time.

After the flowers pass, the fruits begin to form, and then ripe in the fall. They hang on the branches all winter, just like common barberry.

They hang so long, in fact, that you’re likely to see some of last years fruit still clinging to the branches alongside this years flowers.

While they are popular with the birds, they’re so prolific it seems that the birds never seem to clean the branches completely.

All species of barberry have this trait, and you’re likely to find the fruit available on any of them from Autumn into winter and all the way into spring.

Barberry Medicinal Uses

Barberry plants are both edible and medicinal. This applies to all parts of the plant, not just the berries, and the leaves are also commonly eaten. The roots are generally the parts harvested for medicinal use, but the stems and fruits also contain some of the same active constituents.

Traditionally, barberry is used as a general immune tonic and a treatment for gastro-intestinal issues including stomach ache and diarrhea.

According to Mount Sinai Medical Health Center,

“The stem, root bark, and fruit of barberry contain alkaloids, the most prominent of which is berberine. Laboratory studies in test tubes and animals suggest that berberine has antimicrobial (killing bacteria and parasites), anti-inflammatory, hypotensive (causing a lowering of blood pressure), sedative, and anticonvulsant effects. Berberine may also stimulate the immune system. It also acts on the smooth muscles that line the intestines. This last effect may help improve digestion and reduce gastrointestinal pain.”

Not too bad for a plant that grows wild along woodland edges, ditches and roadsides all over the world.

How to Use Barberry

In the Middle East where they’re known as Zereshk, Barberries are usually dried for preservation, so they can be used year round in all manner of dishes.

They’re most commonly used in rice dishes, and if you search “recipes using Zereshk” you’ll get quite a few. Most of them are some variation of this Persian Barberry Rice (Zereshk Polow).

Since they’re high in pectin, the berries are also used to make barberry jam.

When you purchase dried barberries, however, they come without the seeds inside. I’m honestly not sure how you’d practically remove the seeds in mass to make a rice dish, other than passing them through a food mill (which would pulp them and basically make jam already).

Given the seed issue, we mostly just eat them raw in the field. They taste a lot like cranberries, and are quite tart, but I actually love the taste of raw cranberries too. (Be aware, jam might be a better option if you don’t like tart fruit.)

Japanese barberry has a similar flavor, but it’s quite bitter too.

I think they’re fine, but my husband can’t stomach the Japanese species, saying it’s too bitter. He actually spit it out and wiped his tongue after one, but he loved the common barberry species. I think there’s something in them he can taste that I can’t, as I find the Japanese ones a bit bitter, but not too bad.

Either way, common barberry tastes much better, though they’re both edible.

Beyond the fruit, the leaves and new spring shoots are also edible, and they’re used as a green vegetable, seasoning and to make tea.

Since the roots contain the highest proportion of medicinal constituents, they’re usually used medicinally as a tea as well. The roots can be tricky to forage, as the plant has arching thorny branches that reach far from the root base at the center.

The roots are available inexpensively online as its barberry is widely cultivated for both food and medicine, and it’s a lot easier to harvest the roots with farm machinery (that isn’t bothered by the thorns).

Where to Buy Barberry Plants

Since I originally wrote this I’ve had a number of readers ask me where they can buy barberry plants for their garden. We happen to have multiple species of barberry growing wild on our land, so I’ve never considered planting them here.

I did a bit of research and there are not that many places that sell them, likely because they’re considered invasive in most regions. I did find one place online that sells barberry plants, and most of their cultivars are sub-species with colorful foliage.

They’re mostly planted as a border or privacy hedge, which makes sense given their dense foliage and sharp spines. I do not know if any of the cultivars they sell have the same medicinal benefits or edible properties.

My best guess is that they do, but that’s a guess. They’re sub-species of the wild versions that have been selected for their growth habit and color, and the breeders didn’t go out of their way to either keep or eliminate their medicinal or edible properties. (They could be present, or maybe not, so use your best judgment and consume at your own risk.)

Fruit Foraging Guides

Looking for more foraging guides? I have dozens of identification guides for wild berries and fruits…

- Foraging Nannyberry

- Foraging Highbush Cranberry

- Foraging Chokecherry

- Foraging Autumn Olive

- Foraging Serviceberry

I live in Maryland and have been harvesting a lot of barberry (Japanese) this year. I learned a neat harvesting trick – from trial and error / being jabbed by the spikes! When I see a branch with many berries, rather than pick them off one at a time, either with my bare hands or with a thin glove, I reach in and very lightly grab the stem and draw my hand downward (away from the root) and, while the berries fall into my hand, the spines do not stick me! With just a little bit of practice, you can gather quite a few more berries this way.

That’s a great tip. Thanks for sharing.

I’m came here looking for recipes for Japanese barberry jam. I think the ones in the middle east come from seedless cultivars. Perhaps like watermelon, seedless means that the seed is so small as to not be a nuisance, Should I bother running these through my food mill to make jam?

Yes! They make an amazing jam. Cook until soft, run it through a food mill or fine strainer to pull the seeds and then measure the pulp. Mine was quite tart, so I added sugar in a 1:1 ratio to the pulp. It was excellent, and set nicely. Quite sweet for my tastes though, since I like my jam a bit more tart. I think I might do 3/4 sugar to 1 part pulp by volume next time, but if you like regular full sugar jams then a 1:1 ratio is great. Cook the pulp and sugar together until it gels, which is pretty quick.

Great piece! All the practical time and experienced based info so valuable thank you 🙂

You’re very welcome. So glad you enjoyed it.

In county Georgia we add them in to sausages, it adds most amazing flavor!!!

That’s a great tip. Thanks for sharing.

Hello. I’m Persian and very interested to find barberry in Vermont. Could you please tell me where you find these? I would really appreciate it if you could please tell me where In The woods you find them.

Thank you

Oh my goodness, they’re everywhere along roadsides. Just driving in VT this time of year and you’ll see them hung with fruit. If you want one specific bush, I’ll point you to one very prolific bush in a public place. In Montpelier, the parking lot of the VT department of liquor control (13 Green Mountain Dr, Montpelier, VT 05602) has one that’s along the river near the hiking path at the edge of the parking lot. On public land and right in the center of the state, so a good place to look.

We are by White River Junction and they are all in our woods we have hundreds of the plants loaded with berries

I have barberry in my yard, along with many, many other edible plants, but I haven’t tried it yet. I would love to use it for more than jam because I don’t each much jam and I have loads of it as it is (why are so many things preserved as jam?) If it were used as a sweetened pulp, do you think it would be good in yogurt or oatmeal?

Thanks for the detail about knowing whether or not I the Japanese variety. I found two specimens (both having been deposited here by birds) and at first glance, they looked like they might be different varieties. There is also a trail near me with woods FULL of barberries, and I wasn’t sure if they were the native or invasive varieties. Now I will know!

Jam and jelly are really accessible for people, but yeah, you have a great point that SO MANY things are preserved only as jam. For the most part, they’re dried when used traditionally…but I honestly have no idea how they remove the seeds for that method. Some kind of roller method maybe? Or maybe they leave the seeds in? I really wish I knew, but the seeds are so large (and not pleasant in my opinion) that it makes drying them impractical for home use.

It may work to process them in a food mill to remove the seeds, then dry them as fruit leather…then chop into small pieces to use like dried whole berries. Just a thought.

But yes, a dried and de-seeded fruit pulp might be good with oatmeal and other recipes, no need to add all the sugar that’s in jam.

A note should be made that common barberry, Berberis vulgaris is an alternative host for wheat stem rust. For many years the ornamental sale of Berberis sp. was banned in Canada, although it has naturalized in many areas.

Wheat Stem Rust is particularly problematic in the Pacific Northwest.

Thank you so much for sharing that.