Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Hackberries are an incredibly tasty wild fruit, that actually tastes a bit like a sweet fruit covered nut. The outside is pulpy and sweet, like a prune (but with more flavor) and the inside is a crispy nut-like edible seed. Want to harvest a bit of unique wild fruit with a crunch? Learn to identify hackberry trees!

Hackberries are fun little wild edible fruits that don’t fit neatly into any one category. The “fruit” on the outside tastes a bit like a date, and inside, you’ll find a crunchy edible nut. The whole thing is edible and delicious.

Foragers generally pound their hackberry harvests into bars, make them into naturally sweet nutmilk, or just eat them out of hand in the wild.

There is evidence that they were once a substantial food source for our ancestors, but these days they’re often simply planted as ornamental trees or street trees. It’s a shame they’re so seldom used!

They’re delicious, prolific, and nutrient-rich…and once you find a hackberry tree, it’ll produce food for generations.

What is Hackberry?

Hackberry, or Celtis occidentalis, is a large deciduous tree native to North America. Hackberry is in the Cannabaceae or Cannabis family. It’s also called Common Hackberry, Northern Hackberry, American Hackberry, Nettletree, Sugarberry, or Beaverwood.

Is Hackberry Edible?

Hackberry has edible berries that are safe to eat and easy to digest, raw or cooked. The berries are known for being high in calories, fat, carbohydrates, sugars, and protein.

Many homesteaders have also found that Hackberry is a valuable fodder tree for livestock, including cattle and goats.

Herbalists have used the fruit, leaves, wood, and bark of Hackberry in internal medicinal preparations, though they aren’t in common use today.

Hackberry Medicinal Benefits

Historically, several Native American groups used Hackberry in their traditional medicine practices. Some groups made a decoction from the bark for treating venereal disease and sore throats, regulating menstrual cycles, and inducing abortions.

Hackberry has also been the focus of a couple of modern medical studies. One study from 2011 indicated that Hackberry extract has potent antioxidant and cytotoxic activities. These features help protect against damage from aging and diseases like cancer.

The related Oriental Hackberry (Celtis Tournefortii) has also been the focus of several studies. One study found that the antioxidants in a leaf extract of Oriental Hackberry may prevent damage from liver fibrosis, lesions, and other disease. While Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) wasn’t specifically looked at, it may share its relatives’ properties.

In general, Hackberry has been widely ignored in modern times both for its nutritional and medicinal value. This is especially saddening given the Hackberrys’ widespread and important use of the past. Throughout history, people worldwide have relied on their local Hackberries’ dense load of vitamins, calories, minerals, proteins, fats, and sugars to survive. The noted foraging expert Sam Thayer says, “In sheer survival value, it [the hackberry] is unsurpassed.”

Where to Find Hackberry

Native to North America, Hackberry has an extensive range that extends from southern Ontario and Quebec south to North Carolina and west to Oklahoma and North Dakota.

Hackberry tolerates many habitats but grows best in bottomlands, often in the rich soils along streams and rivers. It will tolerate periodic flooding but won’t grow in areas where the water table is consistently high and marshy.

Hackberry prefers areas with full sun but will grow in shade, though individuals in full shade typically aren’t as vigorous. Hackberry is most frequently found on limestone outcrops and soils with alkaline soil, but it tolerates both alkaline and acidic soil conditions.

Since Hackberry tolerates urban conditions, it’s often planted as a shade tree along city streets. As such, you may find it growing in parks, yards, and along streets outside its native range.

When to Find Hackberry

Hackberries typically reach maturity sometime in September across their range. While you can harvest them as early as September, many foragers find it much easier to wait until the leaves have dropped, usually in October or November, to harvest the berries.

Amazingly, Hackberries stay good on the tree all through winter, making them an excellent winter food source for humans and wildlife. In good years, you may find berries as late as April. However, Hackberry production fluctuates quite a bit, and in years with poor yields, wildlife may eat all the Hackberries in early fall and winter.

If you want to harvest leaves for medicinal purposes, it’s best to pick them in spring or early summer while they’re still young and fresh.

Identifying Hackberry

Hackberry is a tree many of us have probably passed without thinking about, but once you know what to look for, Hackberry is easy to identify!

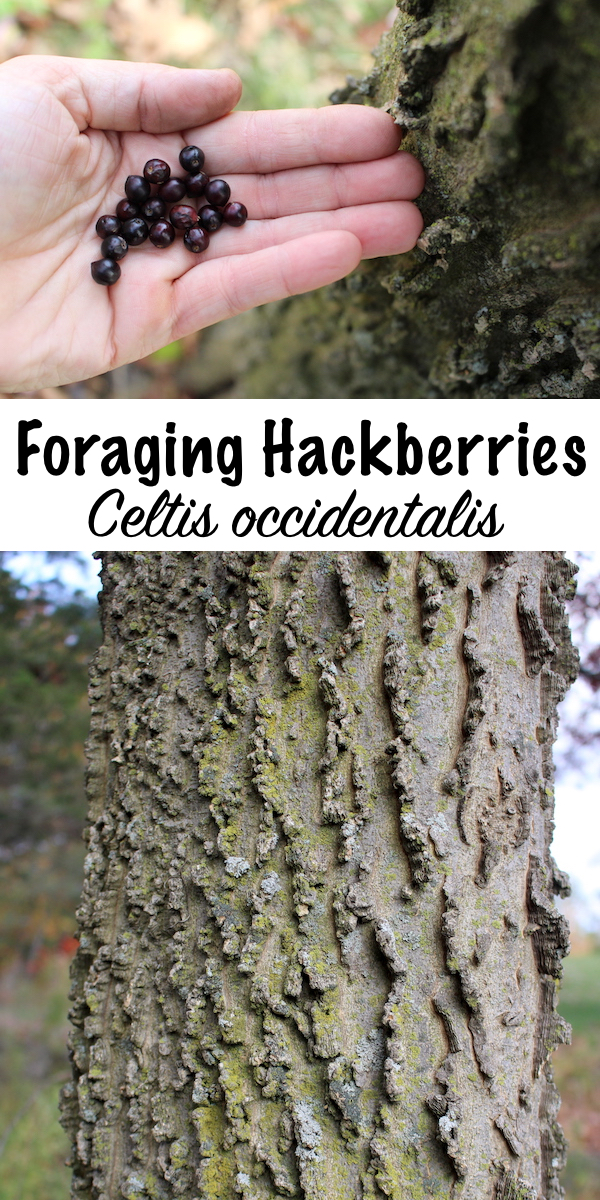

Hackberry is a medium to large tree with a fairly large crown. Its tell-tale bark is one of the best ways to identify it with its distinctive corky, wart-like ridges. Combine the bark with the tree’s slender reddish or greenish-brown twigs, light green alternate, ovate leaves, and dark pea-sized berries, and you have the Hackberry!

Hackberry Leaves

Hackberry has light green leaves. They’re generally lighter colored than many other deciduous species, helping you pick the tree out from the distance.

The leaves are typically 3 to 6 inches long and ovate to ovate-lanceolate. They are often asymmetrical. Hackberry leaves are shallowly toothed along margins except near the base and are rough to the touch.

Hackberry leaves are often infected by an insect called Pachypsylla celtidismamma. This insect causes wart-like growths on the leaves’ lower surface, known as “Hackberry nipple galls.”

Hackberry foliage turns yellow in the autumn.

Hackberry Bark

They grow as medium to large trees that often reaches 50 to 70 feet, though some individuals occasionally grow 100 feet or more. Their branches often form a medium or wide crown.

The bark on the Hackberry’s main trunk is one of the tree’s most distinctive features. It has silvery gray or light brown bark with prominent corky, wart-like ridges. If you look closely, the ridges have layers that make it look like sedimentary rock. Sometimes, the valleys between these ridges are as deep as an adult’s finger and about as wide as a quarter.

Hackberry usually has slender reddish-brown or greenish-brown twigs. These twigs often form quite close together and are sometimes affected by a mite and fungus that cause a feature called “witch’s broom.” This infection causes several twigs to grow from the same point on one branch, forming a broom-like structure.

Hackberry Flowers

Hackberry has tiny, inconspicuous flowers that appear on long stems as soon as the leaves do in spring. The flowers are cream-colored or greenish and have four sepals.

Hackberry Fruit

The flowers give way to pea-sized berries held on the same long stems. The berries have a single round seed and a thin layer of dry sugar pulp covered in smooth skin. The berries ripen to orange, reddish-brown, or dark purple-brown.

Hackberry Look-Alikes

Where their ranges overlap, Hackberry is sometimes confused with Sugarberry or Southern Hackberry (Celtis laevigata). The two can be distinguished in the following ways:

- Sugarberry leaves tend to be smaller, and more lanceolate with narrower tips.

- Sugarberry leaves usually have untoothed margins.

- Sugarberry bark has some warts and ridges but is far less warty than Hackberry bark.

- Witches Broom and Nipple Gall are not common on Sugarberry.

- Sugarberries tend to be juicier and sweeter than Hackberries.

Netleaf Hackberry (Celtis reticulata) is similar to hackberry. However, it can also be easily distinguished in the following ways:

- Netleaf Hackberry grows in the western United States south to Mexico and east to Texas. Its range rarely overlaps with Hackberry.

- Netleaf Hackberry leaves have conspicuous net-like veins on their lower surface.

- Netleaf Hackberry trees usually only reach about 30 feet in height.

Common Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) also has some similarities, but it’s not a close look-alike thanks to these few easy-to-spot differences:

- Common Buckthorn is a small tree or large shrub usually only reaching up to 33 feet in height.

- Common Buckthorn bark is gray-brown, and lacks corky ridges.

- Common Buckthorn branches typically have large thorns or spikes.

- Common Buckthorn has elliptic to oval leaves that may be 1 to 3 ½ inches long.

- Buckthorn berries mature to dark purple or black and each contain two to four seeds.

Ways to Use Hackberry

Commonly ignored today, in the past Hackberries played a huge role in human cuisine and medicine wherever they grew. These berries have been found in archeological remains all over the world from the Meadowcroft Tock Shelter in Pennsylvania, dating to 19,000 years ago to the “Peking Man” site in Zhoukoudian, China dating to 500,000 years ago.

Though they’re unlike any of our cultivated fruits, Hackberries are a great find for any forager today. They’re highly nutritious and full of fat, protein, and calories not found in other fruits.

To reap all these rewards it’s necessary to consume the entire Hackberry including the seed and flesh. They’re quite crunchy but are easily digestible. You can also process them with a grinder, mortar and pestle, or high speed blender to eliminate the crunch.

Their texture may take some getting accustomed to, but Hackberries make excellent additions to granola bars, pemmican, custards, and desserts once processed. Their thin flesh has a sugary, almost date-like flavor.

If you don’t mind the crunch you can eat them whole right on the trail! Some foragers liken them to eating peanut m&ms with a thin layer of sweet and crunchy protein-rich center.

As hackberries are rich in antioxidants, including them in your diet can also help boost your immune system and keep you healthy. Experienced herbalists may also want to experiment with teas or tinctures from the berries, bark, and leaves. However, very little information is available on Hackberry’s medicinal use, so it’s best to proceed cautiously.

Hackberry Recipes

- The Forager Chef has an excellent recipe for Hackberry Candy Bars that make a great on-the-go sake for foragers!

- The Black Forager also has a fun short on quickly processing your hackberries into bars.

- You can also process your Hackberries into milk with this great recipe from Emily Han. She recommends sweetening the milk and enjoying it as is or using it to make tasty smoothies, custards, puddings, or other desserts.

- If you’re not a fan of the seeds, try this recipe for Hackberry Jam from Wild Edible Plants of Texas.

- If you find a lot of Hackberries, Plant Assasin has a helpful video on how to prepare them for storage.

Edible Wild Fruits and Nuts

Looking for more edible wild fruits or wild foraged nuts? These foraging guides will keep you busy!

- Foraging Autumn Olive

- Foraging Chokecherries

- Foraging Wild Black Cherry

- Foraging Beechnuts

- Foraging Black Walnuts