Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris) is one of the first wild edible plants of spring. It’s commonly cooked as a pot-herb, and people once welcomed it to their tables after a long winter of stored food.

Spring is always slow to arrive here in the North country, and we don’t see our first dandelions until mid-May. Contrary to popular belief, however, dandelions are nowhere near the first flowers of spring.

Months before the first dandelion, hardy spring greens like marsh marigold, stinging nettle, chickweed, yellow dock, and burdock send out tender edible green leaves.

Not too long after that, the bees go to work on sweet maple flowers high in the trees and then make their way to the swamps to sample the nectar from carpets of marsh marigold blossoms.

Where to Find Marsh Marigold

As the name suggests, marsh marigold thrives in wet soil. Much of the area around our woodland homestead has shallow clay soils, and low spots stay wet for a few days after heavy rains. Add in a bit of shade, and you’ve got the perfect environment for a field of marsh marigold.

Look for marsh marigold in wet ash and alder stand, or in swampy ditches, near springs or around ponds.

Caltha palustris is native to most of the US, especially in the north (range map here), as well as all of Canada, and much of Europe and Asia.

Most of the year, marsh marigold looks like indistinct low-growing green foliage, easy to miss in a casual glance. For a few weeks every spring, however, that same patch will light up with bright yellow flowers that are impossible to miss.

Identifying Marsh Marigold

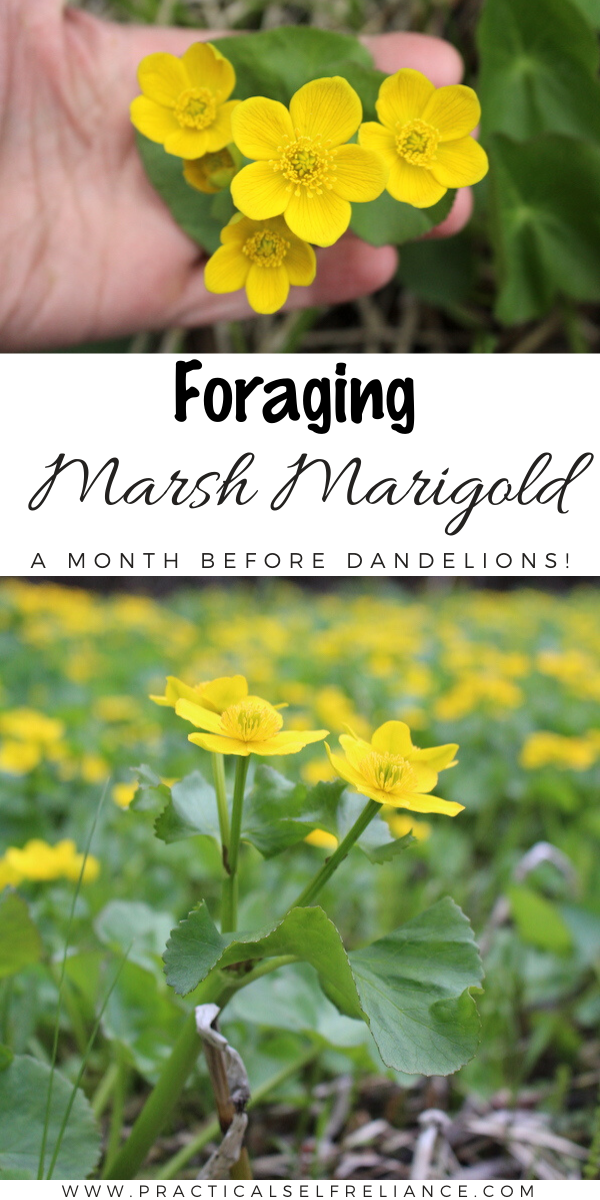

As a member of the buttercup family, marsh marigold has buttercup-like flowers with 5 to 9 “petals” (actual sepals that look like petals).

I’ve only seen them with 5 around these parts, but sources say they can have 5 to 9, generally in odd numbers.

The plants themselves are low growing, 12 to 18 inches high at most.

Marsh marigold leaves are slightly toothed and kidney-shaped. From a distance, they appear round, but on closer inspection, you can see that they have a deep cut where the stem attaches at the bottom of the leaf.

Marsh Marigold Look-Alikes

To the best of my knowledge, marsh marigold has no harmful look-alikes. It does, however, grow in locations often populated by other poisonous plants, namely water hemlock.

Obviously, when foraging anything, pay attention and don’t just grab for leaves carelessly. Water hemlock, and other potentially dangerous water-loving plants, look nothing like marsh marigold, but careless harvesting could obviously be dangerous.

There is a related species western marsh marigold (Caltha leptosepala) that’s also reportedly edible. It looks very similar but has white flowers.

Harvesting And Using Marsh Marigold

Like most greens, marsh marigold is best when young and tender. The small leaves are harvested for use as a cooked green. Leaf stalks and young, unopened flower buds are also edible.

It’s actually best to find a plant early, just as it’s breaking bud but before the flowers have opened. In Vermont, that’s Mid to late April, but they can often still be harvested through the end of May.

The leaves remain tasty all through the bloom cycle, so they can still be harvested when marsh marigold is easiest to identify. Once the bright yellow blossoms disappear, however, the plant is past its harvest window.

I’ve read some reports that people eat it raw, but that’s not advised. Marsh marigold contains a small amount of toxin (known as Protoanemonin), the same toxin present in other plants of the buttercup family. It’s very mild in marsh marigold and is easily removed by boiling.

Some have reported mild reactions when touching the leaves, so be aware that’s possible. I generally don’t react to much, and marsh marigold causes no issues for me.

Harvest young leaves and stems when they’re 1 to 3 inches across. Keep in mind that they’ll shrink dramatically when cooked, so you’ll need quite a bit to make a dish.

Cooking Marsh Marigold

Directions for cooking marsh marigold vary quite a bit, largely based on personal taste.

Some suggest boiling for 20 minutes and then straining and rinsing. Others suggest boiling for a total of 60 minutes, with water changes every 20 minutes.

The longer you cook them, the milder the flavor becomes, though I found them pretty mild even after just brief cooking.

I’ll be honest, I’m not a huge fan of cooked greens. I won’t touch cooked spinach…and yet I fell in love with marsh marigold.

It’s not much to look at in a bowl, but they maintained an agreeable texture even after extended cooking and they had a succulent quality, not unlike purslane.

While I love the taste of marsh marigold, I’m in the minority. I’ve read others that consider it a survival food, or barely palatable. Others still use it as a base for gravy or slather it in salt and butter.

Most foragers find the plant more of a historical curiosity, as a memory of a time back before year-round salads imported from warmer climates.

Sam Thayer captures this sentiment well in A Forager’s Harvest, noting that:

“The main attraction of marsh marigold is that it is abundant and easy to recognize, offering itself as a potherb over a month in advance of the earliest garden produce. There was a time when the springtime craving for wholesome fresh vegetables and dietary variety meant more to backcountry folk than the instant gratification of mere flavor.”

Honestly, I just love the fact that marsh marigold got me foraging in a new environment. I’m not often digging around in boggy ditches, and while I was down there I spotted tasty willow flowers, autumn olives, highbush cranberries and a big patch of wild gooseberries.

I started developing an interest in the fruits of these out-of-the-way wet places and fell in love with wild raisins, nannyberries and all manner of wild edible fruits that I wouldn’t have discovered had I not ventured off the beaten path.

If you spot a patch of marsh marigold, take a minute to check it out. Even if you’re not in the market for spring greens, you may well find something tasty to tempt you back to that spot later in the season.

More Early Wild Edibles

Looking for more plants to forage this spring?

- Edible Garden Weeds

- Recipes Using Dandelions

- Recipes Using Lilacs

- Foraging Miner’s Lettuce

- Foraging Wild Asparagus

- Foraging Japanese Knotweed

I’m in my 50’s now and have moved to Florida. This is one of the reasons I miss the north (along with dandelions) my Dad harvested these since probably before I was born! We did the bring to a boil, cook for 20 minutes and change the water and repeat 2x more (the 60 minute cook) next to nettles it was my favorite spring green!! We harvested only when the buds were closed (those were yummy themselves) . On the last boil, Dad added a little bacon then when cooked we added butter and vinegar…… YUMMMMMMMM

Sounds absolutely wonderfully. Thank you for sharing.

Not sure it grows in my area, Pacific Northwest, but am going to look into the western variety you mentioned. Here, in the desert of south eastern Washington “Biscuit Root,” also called “Desert Parsley, along with Cottonwood buds are the name of the game right now.

https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Ficaria+verna

À le Euell Gibbons. He suggests making capers from the early bud clusters.

Here is a good link explaining the differences between Marsh Marigold and Lesser Celandine: https://www.lhprism.org/blog/invasive-lesser-celandine-vs-native-marsh-marigold

I was just wondering what these pretty flowers were! They are starting to bloom now in Central PA. The ones I’ve seen have 9 petals.

Would you say Marsh Marigold has a bit of a waxy leaf? Just want to be sure on identification…

Yes the leaves are often described as waxy.

Hi…

I just found a patch of Marsh Marigolds and am curious to try them. Will you tell me how you prepare them please..? I don’t want to overcook the goodness out of them but, I don’t want to leave any toxins either. Also…do you cook the leaves and flower buds together..?

The recommendation is 20 to 60 minutes. I would start off with 20 minutes and then add additional time according to your taste preference. They will become milder in taste, the longer they are cooked.

Please be very careful when foraging marsh marigold in the Midwest. There is an insipid invasive look-alike called Lesser Celandine, which has been taking over lawns and gardens here. It dies back after the spring bloom and ten the bare spots sport clumps of new growth from seeds of many other opportunistic weeds.

That’s very interesting. Thank you for sharing.