Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Solomon’s Plume (Maianthemum racemosum) is a tasty native edible berry that’s common, easy to spot, and abundant all across the US, Canada, and Mexico. It goes by many names, including False Solomon’s Seal, False Spikenard, and feathery False Lily of the Valley.

With all those “false” common names, you might get the impression that Solomon’s plume isn’t all that desirable, but while it may look vaguely similar to other common plants, Solomon’s plume is the best of the bunch in my book.

A “false” anything sounds like trouble, right? If you hear false morels you assume they’re probably toxic, and the same for false chanterelles. (You’d be right.)

In this case, the “false” variant of Solomon’s seal is actually the tastier option. (And “true” Solomon’s seal berries are actually toxic. Tricky, I know…)

Most people probably know (Maianthemum racemosum) by the common name False Solomon’s Seal, as in many ways, the growth habit and leaves look similar to true Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum biflorum). In flower and fruit, however, the plants are incredibly easy to tell apart.

False Solomon’s seal, or Solomon’s plume, has a plume of flowers at the end of its shoot. They’re really beautiful in the summer months, and the tiny white flowers almost glow when they catch the sunlight.

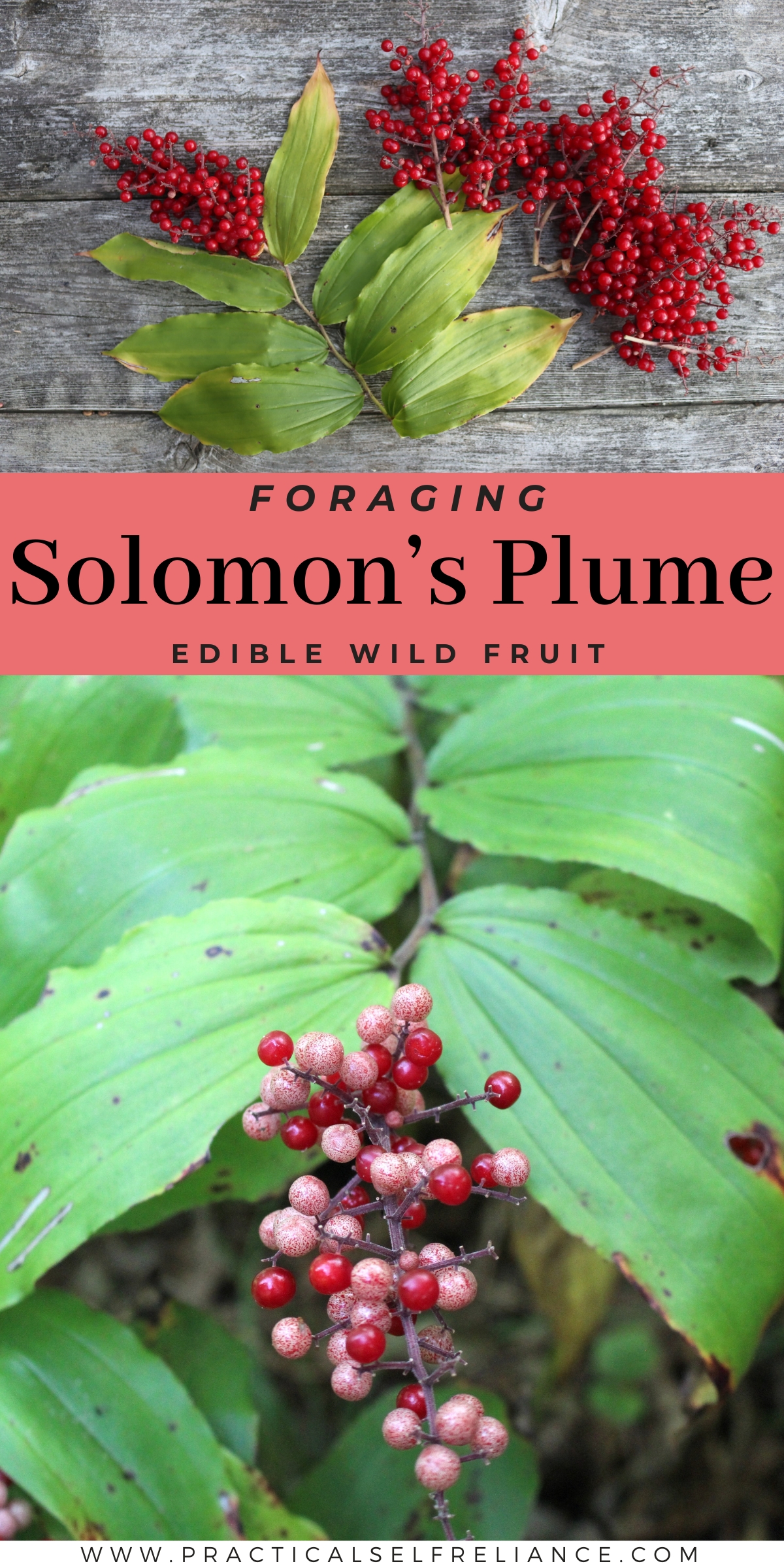

After the stunning white flowers early in the season, the berries begin maturing. They go through a phase where they’re speckled in a way that’s characteristic of plants in the Maianthemum genus. A good example is Canada Mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), which has similar berries in the fall but a different growth habit.

The speckled berries are almost more eye-catching than the fully ripe red berries, just because they’re so unique.

Eventually, they’ll develop into a deep ruby red when truly ripe.

Here in Vermont, they ripen in very late summer or early fall, starting in early September and continuing to ripen through October.

In warmer and more southern climates, I imagine they ripen earlier.

Inside the fruits, you’ll find a single large very hard seed that looks a bit like an eyeball (and is hard as a rock). The skins are very firm, then just beneath is a layer of jelly-like sweet fruit, and finally this hard seed.

The sweet pulp is sucked off the seed, and then the seed is discarded.

The fruit are often harvested by birds and other small woodland animals, but the later ripening fruits may just get blanketed under a cover of snow.

Sometimes, they’ll persist all winter, and I’ve found them still reasonably fresh at first melt in the spring. (They’re a fun treat to find out winter foraging, but without the other clues for identification, be extremely careful with out-of-season harvesting.)

I personally really enjoy the berries and find them sweet and pleasant. Some foragers don’t enjoy them, and I imagine there must be something that people can taste and others can’t. (Like how some people think cilantro tastes like soap.)

Sam Thayer describes them in one of his foraging guides, and clearly he can taste a bitterness I don’t detect:

“The flavor of false Solomon’s seal is quite unexpected: molasses-sweet at first, fading to an overbearing dose of bitter/acrid flavor that permeates every part of the plant in varying concentrations. This acrid taste is too strong for me to enjoy more than a few berries, but the sweetness coaxes me to reach for another nibble later.”

He notes that they tend to taste better out west, but I’m here in the far Northeast, and I love them. I get a very slight acrid aftertaste, but it’s subtle and barely noticeable.

My kids agree with me, and don’t taste any bitterness. They stain their hands harvesting the small, soft fruit.

The fruit can be harvested in large quantities when ripe, as they grow in colonies. I’ve considered putting these through my Chinoise sieve and making a fruit butter out of them. There’s actually a number of recipes for such in the book Wild Jams and Jellies.

What stops me? Some sources note that the fruits are laxative in large quantities. With that in mind, I stick to eating them out of hand fresh on the trail (and I’ve never had any issues). Maybe they’re eating the slightly underripe speckled berries?

Solomon’s Plume Look-Alikes

While I consider Solomon’s plume pretty easy to identify (at least in the fruiting stage), it does have a number of look-alikes, all of them toxic.

Outside the fruiting stage, it has many more look-alikes, and I don’t recommend trying to eat other parts of the plant unless you’ve done your research.

Be careful when foraging this plant, and as with foraging any wild plant, it’s important to be 100% certain of your identification.

(Always consult at least two ID guides, don’t just take my word for it!)

Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum odoratum)

I don’t really consider Solomon’s seal to be a look-alike, since the berries are completely different and it’s easy to tell them apart when you’re harvesting the fruit. (If you happen to be harvesting the shoots or roots of the plant when it’s not in flower or fruit, then they are quite similar and you’ll need to do a bit of work here on identification.)

Solomon’s seal bears just a few flowers under its main stem at each leaf node, unlike Solomon’s plume which has…a plume.

They develop into dangling blue fruits that are actually toxic, though the roots are edible for ambitious foragers. (For details on harvesting true Solomon’s seal, I’d suggest reading Nature’s Garden by Sam Thayer.

(It also has detailed information on harvesting Solomon’s plume, including how to identify and harvest it in early stages if you’d like to try the shoots and rhizomes. His books are by far my favorite foraging guides.)

Jack in the Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

This one’s a stretch, but I have actually seen people misidentify jack in the pulpit fruit as all manner of edibles, basically anything that has a red berry. It’s common in the woods, and I often find it near Solomon’s Plume.

The first is Jack in the Pulpit fruit, which is born on a short spike that seems to appear from nowhere out of the ground. The plant’s already died back, just leaving these bright red berries that you might actually confuse for the eggs of some insect.

Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra)

The second is Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra), which is incredibly toxic and does actually bear a vague resemblance to Solomon’s plume (at least in the fruit). In fact, if you do an image search for red baneberry you’ll actually find a number of pictures of Solomon’s plume mistakenly mixed in there. Clearly, people confuse them often enough…

The plant’s growth habit and leaves look nothing alike to my eye, and the fruit themselves have a black dot on them. (Similar to white baneberry, also known as dolls eyes.) Still, be absolutely sure about your identification before trying Solomon’s plume, as a mistake here could be fatal.

Be careful out there, and be sure to check with other sources before you forage this (or any other edible wild berry, fruit, or plant).

Foraging Guides

Looking for more edible wild fruit out there in the wild?

Here we call it by the common name treacleberry, because of the flavor.

I live in Northwestern Canada and they are super sweet. No bitterness at all. I eat the young leaves and of course, the shoots. There is a toughness and bitterness to the more mature leaves. One thing I really enjoy are the flowers plumes of the False Solomon Seal. Most people don’t know they are edible. Harvest them when they are fluffy and white. A bit of green/yellow tip is fine, But as the flower matures, it gets more tough and chewy. I use them in salads and they make great fritters and they are a hardy flower. And yes, the berries are awesome as a trail snack!

Wow, that’s the name I’ve been using since I got tired of calling them “false,” but I’d never heard anyone else use it! I didn’t know they were edible—looking forward to trying them.