Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Foraging wild grains and seeds was once a way of life for humans around the globe. There are literally hundreds of species of edible seeds, far more than the cultivated grains that make up our staple diet these days.

Every year, a bit after groundhog day marks the middle of winter, I start to see wild seeds and grains everywhere. It seems like a strange time, I’ll admit, but that’s usually when I’ve exhausted my interest in all the other things you can forage during winter.

I’ve already harvested usnea lichen downed by winter storms, pulled baskets full of highbush cranberry and nannyberry from their frozen branches, and done everything conceivable with the rose hips that have been sweetened by winter frosts. We’ll harvest crabapples all winter long, and I’ve been drinking pine needle tea for months by this point.

Winter mushroom foraging has mostly filled my larder with medicinal mushrooms like Chaga, birch polypore, and tinder polypore, as well as a few choice tasty edible mushrooms like cold-loving lion’s mane mushrooms.

We’re still around a month away from making homemade maple syrup, and two months away from tapping birch trees.

It’s a dead time for foraging, or so you would think. That is until you open your eyes to all of those seed stalks sticking out through snowdrifts, holding their tasty prize and waiting for spring winds (or birds) to disperse the seeds as the growing season begins.

This year, I also happen to be reading Jean Auel’s Earth’s Children Series, which is hands down the very best historical fiction for foragers ever written. I say “historical” but really it’s anthropological. As with any fiction, it has romance and human interest and all that, but this particular series is written by an author with a passion for neolithic technology and living. She describes the tools used for hunting and fire starting in detail, and she also describes every element of the landscape as they’re passing through different environments.

I’ve been a serious forager for more than a decade, and her descriptions are spot on. Everything is in the right season, the right soil type and she knows just how to prepare every single thing her characters encounter. In all her books, I’ve only seen one (relatively minor) error, when she states that beech nuts are delicious but hard to crack. Beech nuts are delicious, but they’re really easy to crack. I suspect she meant butternuts, which are also delicious, but nearly impossible to crack.

That’s it though, a single minor error in more than 5,000 pages of detailed anthropologically correct fiction. Amazing work.

Anyhow, I digress…but if you’re enough of a foraging nerd to be reading an article about wild grains and seeds, you should definitely read all of her books.

One thing she does often take time to mention is their use of wild grains and seeds, and how they harvest them opportunistically as they’re moving through the landscape. A handful of this, another of that…never enough to make a loaf of bread or a bowl of rice…but plenty to add variation, texture, and nutrition to meals.

When you’re living on a diet of dried stored meat all winter, or traveling and living on pemmican (dried meat/fat cakes), then a handful of grain goes a long way to making a soup nourishing, thick and rich with nutrients that meat alone cannot provide.

Just because you’re eating grain, doesn’t mean you’re eating bread. Good bread takes gluten, which is something that’s mostly restricted to wheat, and most modern wheat varieties at that. It’s not something that was common in grains before agriculture, and there are literally hundreds of types of grain eaten by humans long before the advent of agriculture.

Some, like teff in Northern Africa, are so small they look tiny next to grains of sand…but they’re still harvested in en-masse. (Teff flour is delicious by the way, you should try it. The whole grains of Teff are also amazing, and rich with a flavor that’s not common in the bland grains consumed by most of society today.)

Here in the US, there are hundreds of native grains and seeds that were used (and still are used) by native peoples to add texture and nutrition to their diets. Researchers at The University of California Berkley wrote a paper on more than 200 different seeds and grains used by native Americans on the west coast alone. (The full text is available free online here, and it’s more than 200 pages of detailed information.)

Across the country that are many, many more species of edible grains and seeds. Think about all the native plants across the rest of the country, as well as imported wild plants from Europe that were eaten by prehistoric humans there, and then came over with settlers in more recent history.

To me, this is an amazing opportunity for exploration. Or, more accurately, rediscovery.

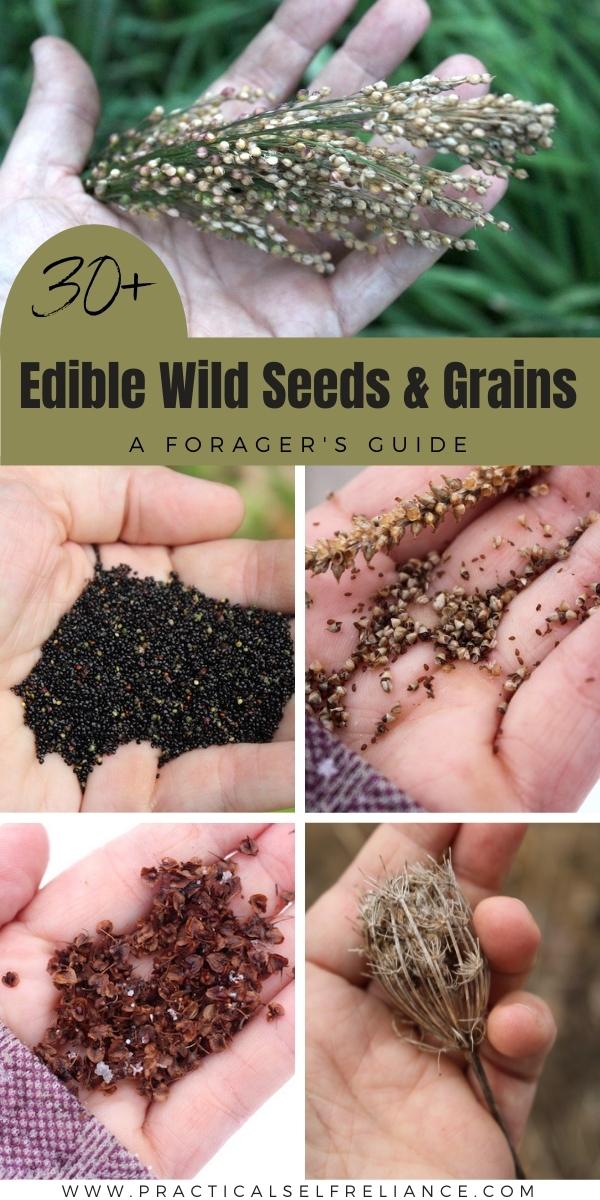

Edible Wild Grains and Seeds

There are hundreds of tasty seeds out there, and this year I’m hoping to find as many as possible. At this point, I routinely harvest around a dozen different types of wild seeds and grains, and by the end of this year, I hope to add a few dozen more.

Though I generally get focused on wild grains and seeds mid-winter, it’s not actually the best time to harvest most species. There are quite a few that hold their seed heads above the snow, but others, like wild millet, are only available for a short while after they ripen in late summer or early autumn. The really calorie-rich seeds are obviously snatched up by opportunistic wildlife quickly, and those left in winter are just late-ripening varieties (or those that aren’t the most calorie-dense).

This year, I’m going to work on identifying and foraging seeds during the growing season too, not just in winter.

I hope to use this article as a starting point for discussion, and I’d encourage you to leave your knowledge and experiences with wild grains in the comments.

These are the wild grains and seeds that I know, and I’d ask that you as my fellow foragers add to the list to help make it as complete as possible. With more than 200 species traditionally harvested in California alone, we’re going to need to crowdsource this effort!

List of Edible Wild Seeds and Grains

All of these are, to the best of my knowledge, edible seeds that can be collected in the wild. (Always verify with multiple sources before consuming any wild plant, AND make sure you’re 100% certain on your identification.)

- Amaranth (Amaranthus sp.)

- American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea)

- Angelica (Angelica sp.)

- Ash (Fraxinus sp.)

- Black Mustard (Brassica nigra)

- Black Sage (Salvia mellifera)

- Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

- Caraway (Carum carvi)

- Chia (Salvia columbariae)

- Chickweed (Stellaria media)

- Claytonia (Claytonia perfoliata)

- Cleavers (Galium sp.)

- Crabgrass (Digitaria sp.)

- Dock Seeds (Rumex sp.)

- Evening Primrose (Oenothera sp.)

- Field Mustard (Brassica rapa)

- Flax (Linum sp.)

- Goosefoot Seed or Wild Quinoa (Chenopodium album)

- Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

- Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya sp.)

- Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- Mallow (Malva sp.)

- Maple (Acer sp.)

- Millet (Panicum miliaceum)

- Nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus)

- Plantain (Plantago sp.)

- Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

- Rocky Mountain Pond Lily (Nuphar lutea)

- Ryegrass (Elymus canadensis)

- Sedge (Cyperaceae sp.)

- Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

- Sunflower (Helianthus sp.)

- Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

- White Sage (Salvia apiana)

- Wild Celery (Apium graveolens)

- Wild Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

- Wild Mustard (Descurainia and Lepidium spp.)

- Wild Oat (Avena sp.)

Using Wild Grains and Seeds

Wild grains and seeds aren’t always used as a straight source of carbohydrates, as rice or quinoa is today. If you’re incorporating these into your diet, there are only a few that really can stand up to treatment as a straight side dish, and those are the wild ancestors of our modern grains (wild rice, wild oats, and wild millet).

For the most part, wild seeds are best when used to add texture to meals. A handful in a stew, or as the topping on crackers. There are a few wild grains that can be ground into flour for use in baking, namely dock seeds, but those are the exception.

For the most part, you’ll be using wild steeds to add flavor (as in wild carrot seeds), or as a thickener (as with mallow seeds or plantain seeds).

Toxic Grains and Seeds

Just because the plant itself is edible, doesn’t mean that the seeds are edible as well. Different parts of different plants are toxic, and even when working with medicinals, different parts can have different actions.

Mullein, for example, is edible including its roots, leaves, and flowers. The seeds are toxic and have been used traditionally to stun and paralyze fish in traditional fishing practices.

If you watch the birds, especially woodpeckers, they’ll land on mullen seed stalks and carefully pick out the seeds in the spring months. What’s edible for the birds isn’t always edible for humans. Be careful when working with any wild food, and be sure to do your research, consulting at least two sources before trying anything.

Make sure you’re 100% certain on your identification, as many guidebooks don’t offer much guidance on foraging wild seeds and grains. Or, more importantly, identifying edible species when they’re past the leafy green stage and have matured their seeds.

Queen Anne’s Lace, for example, has tasty seeds that add amazing flavor to crackers and salads…but it looks very similar to deadly poisonous water hemlock. Sometimes it’s easiest to identify the plant during the growing season, and then mark it to come back for seed/grain later.

In the end, you’re responsible for your own safety when foraging. Even when something’s generally considered edible, it may not be edible to you, and there’s always the possibility of a reaction.

Personally, I have a severe reaction to the pods of Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya sp.), yet I find the seeds tasty enough if I’m careful when taking them out of the casings (and I keep them away from my body until they’re husked). Everyone’s going to have different sensitivities.

Foraging Cautions

Please use this as a jumping-off point for your own research, but don’t simply take my word (or anyone else’s) before eating a wild plant. Always do your own research, consulting a minimum of two qualified sources, preferably more.

It’s always possible to have a reaction to any wild plant, even ones generally considered safe and edible. Always test new plants with caution, and only if you’re 100% certain of your identification.

I’d suggest investing in regional foraging books for your area, or going out with a knowledgeable forager in your region. Lacking that, the online Botany and Wildcrafting Course from the herbal academy is an excellent guide. I’ve taken many courses from them and they’re always informative, inspiring, and artfully presented.

The Book New Wildcrafted Cuisine by Pascal Baudar has the best section on foraging and using wild seeds in any foraging book I’ve ever seen, and I’d recommend that one if you intend to further your research.

Wild Plant Lists

Looking for more lists of edible wild plants to forage this season?

- 50+ Wild Plants to Forage in Winter

- 20+ Wild Plants to Forage in Spring

- 50+ Wild Edible Berries and Fruits

- 20+ Edible Roots, Tubers, and Bulbs

Thank you for sharing this empowering information.

Has anyone tried four winged saltbush seed? I live in the Southwest and a park ranger said they are/were eaten by the people here.

I’ m using it in small doses in granola.

So far so good.

I have not, but it’s not something we can get around here. A book just came out with many of the edible seeds of the Southwest by Pascal Baudar. Maybe he discusses it?

I couldn’t see comments until I commented – so I see there’s a new link for the forest service book! thanks —

Hi, Ashley! Two things: 1) the link to the UC Berkeley document on seeds & grains used by coastal indigenous peoples didn’t work for me. 2) Question: are ALL sedge seeds edible? Thanks —

I have been trying to find a good answer to that question on sedge for some time, but with no luck. We have so many species of sedge here and I’ve tried their seeds (and nutlets underground) and haven’t found many that were tasty…but as to their specific edibility (safety wise) I don’t know. None are known as specifically toxic, as far as I can see, but I think this is just one of those places where there’s not a great record one way or the other.

Here in my back yard of Missouri, USA, there is wild Queen Anne’s lace, purslane, plantain, mullein, and those I have added to the yard including evening primrose, sunflower, goosefoot, jewelweed, marshmallow, nasturtium, stinging nettle and sunflower, many of which I did not realize had edible grain or seed. I am sure that there are many other of these plants around that I’m not yet familiar with (amateur forager of 2 years), so this will give me something to do this winter where I would be otherwise twiddling my thumbs, awaiting spring. Thank you for bringing up the fact that these will be used as additions to meals, less a main staple. Very thorough. Thanks for the book suggestion, the Earth’s Children series.

You’re very welcome. We’re so glad you enjoyed the post.

The forest service grain book has moved: https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/ethnobotany/documents/EdibleSeedsGrainsCaliforniaTribes.pdf

Thank you for sharing.

I am looking for wild edible plant seeds to purchase for educational and forging purposes….

I’m sorry but we don’t sell seeds. Do you have areas that you can forage that are local to you?

Another wild grain I learned about just recently is Lyme grass (leymus arenarius). It’s supposed to be extremely high in protein and grows even high up north (I found it here in Norway but the internet told me that the vikings even gathered it in Island). It developes grain even in years when “domestic” grains fail due to drought or cold weather. I’m found a big patch and can’t wait for it to ripen and bake a viking bread 😀☺️

That’s great. You should come back and let us know how your bread turns out.

The Jean Auel series is SO incredibly good! Widely under appreciated! It has fueled my passion for foraging and herbal medicine since I was a young teen! Thank you for this very informative article.

You’re very welcome. We’re so glad you enjoyed it.

Thanks for this! It is intriguing and useful.

You’re quite welcome!