Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Wild violets are a beautiful addition to the landscape every spring, and they also happen to be both edible and medicinal.

They’re easy to identify, and all species of violas (wild and cultivated) are edible, so there are plenty of opportunities to forage violets (even if you’re just “foraging” the garden pansies.)

My mom has a special love for wild violets, and she was amazed to see them growing wild all over our land here in Vermont.

In California, she actually grows them in her garden, carefully tending them with drip irrigation. They like moist soil and shade, which isn’t all that abundant in the Mojave.

Still, she plants them underneath trees as a shade-loving ground cover, propagating year after year from violet root divisions (and allowing them to self-seed.)

For those of us living in more reasonable climates, violets are carefree additions to the wild landscape. They’re likely to come up in moist spots on the lawn, especially in shady areas underneath trees or alongside the north side of the house.

They’re also abundant in the woods and at the edges of fields where they’ll get enough shade to thrive.

Where to Find Wild Violets

Violets are either incredibly abundant, or hard to find, depending on the soil conditions.

My first home in the northeast had beautiful gardens and fertile, well-drained soil that was perfect for growing anything…except violets. On the rare occasions, I’d spot them in the woods, I’d think of them as a rare treasure and visit those little patches all spring.

Then I moved to our Vermont homestead, where the woods have shallow soils, and dense shade abounds. It’s known as a “mesic forest”, where the soils stay wet (but not swampy) year-round.

It’s the ideal environment for lots of wild edible plants, like linden trees and beechnuts. And it’s perfect for wild violets.

Wild violets are abundant across the entire US, provided the soil conditions are right. It’s often that low shady spot in the lawn, or next to that mud puddle along a forest trail. Or in a shady wet meadow.

Anywhere with shade and consistently moist soil.

You’ll sometimes find them growing in full sun, provided the soil is relatively heavy and has consistent moisture. One of our gardens happens to have heavy, wet soil and naturally grew a carpet of violets even in full sun.

When Do Wild Violets Bloom?

Wild violets are spring flowers, and in mild climates, that can be February or March.

Here in Vermont, we don’t see them until Mid-May (alongside the dandelions and lilacs, both of which are also edible flowers).

Identifying Wild Violets

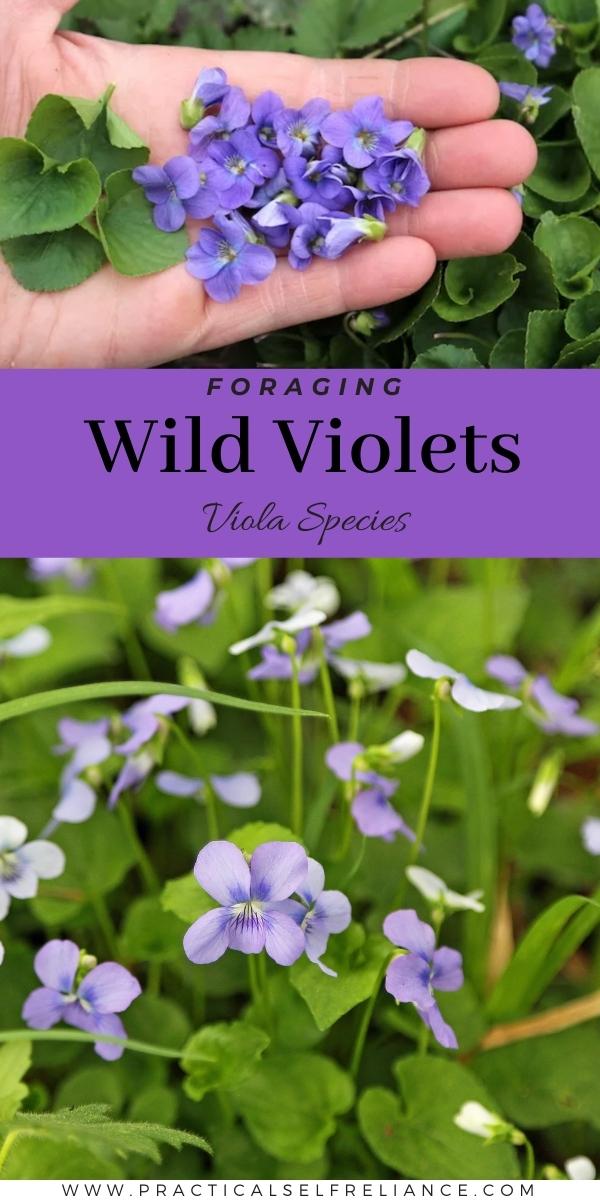

I’m going to stick with the characteristics of wild violets, namely viola sororia, which are the small-flowered violas with blue/purple blossoms, and occasionally white blooms.

There are many types of cultivated violas that escape into the wild since they readily self-seed.

Wild Violet Flowers

The flowers of wild violets are the most telling characteristic, and one of the best ways to identify them. They have 5 petals, always in a “star” shape with the point of the star pointing down.

Two petals point upwards, two out to the sides and one downward. The center of the flower is usually streaked with another contrasting color.

Each flower comes on its own leafless stalk, emerging from the center of the base of the plant.

By far the most common color is blue/purple (or violet, for obvious reasons), but they also come in white and occasionally yellow.

Wild Violet Leaves

The leaves of wild violets are smooth and hear shaped, and the heart “lobes” often curl toward the leaf stalk. Each leaf is on its own stem, which emerges from the base of the plant.

Leave are a dark green color when the violets are in full shade, and much larger.

When grown in sun, the leaves tend to be a light green and are much smaller.

Violet Look-Alikes

For the most part, violets don’t really have any lookalikes. At least not violet flowers.

The heart-shaped or rounded leaves can look like other plants, so it’s best to wait until they bloom before harvesting.

Some people say that violet leaves look a bit like Lesser Celandine (which is toxic) and Marsh Marigold (which is edible). I say a bit…but not a lot like violet leaves. It takes work to confuse them, but still, better safe than sorry if you’re identifying violets for the first time.

Both lesser celandine and marsh marigold have bright yellow flowers that look nothing like violets, so once violets bloom identification is pretty foolproof.

Are Violets Edible?

All violets are edible, including wild violets or cultivated viola species.

There are a number of traditional dishes made with violets, including Creme de Violette, a herbal violet-infused liqueur made with wild violets harvested in the alps.

In the victorian era, it was popular to press violets into the tops of cookies or make crystalized violets by coating the flowers in sugar.

These days, edible flower jellies have become incredibly popular, and violet jelly is one of the very best. The delicate floral notes are lovely, and it actually tastes a bit like fresh berries.

Harvesting Wild Violets

How you harvest wild violets depends on your intention.

The flowers may be beautiful, and delicious, but they’re not the medicinal part. They’re mildly diuretic, but only mildly, and mostly they’re just a tasty edible flower.

The leaves are potent medicine for lymphatic issues, and they’re used both topically (in violet salve) and internally to promote lymphatic health. They’re also used topically for inflamed skin, rashes, hives, and eczema.

Violet leaves contain substantial amounts of mucilage, which makes them good for digestion, as well as sore throats and coughs.

That same mucilage makes them a bit gummy to eat fresh, though many people do enjoy violet leaves added to salads.

Still, most people are drawn to the flowers instead of the leaves, and flavor instead of medicine. Harvesting violet flowers for use in the kitchen is the most common.

We happen to have really big patches of both the blue/purple varieties and the white varieties, and this past spring my daughter decided it’d be fun to make things with each of them (separately).

She absolutely loves edible flowers, and she’s the main reason I have half a dozen dandelion recipes posted (everything from dandelion ice cream to dandelion cookies, and even dandelion marshmallows).

This particular experiment was fun, but we learned that they both taste quite similar. The purple is slightly better in her opinion, with more flavor and a bit more “berry” notes from the same antioxidants in the pigments that give blueberries their taste.

White violets are more delicately flavored and more floral (less berry).

Ways to Use Wild Violets

Wild violets can be used just about anywhere you’d use a medicinal flower. They make beautiful additions to salads, and they’re deliciously eaten right out in the wild.

If you’re looking for a special project, try any of these violet flower recipes:

- Violet Jelly

- Wild Violet Muffins

- Wild Violet Sugar

- Violet Simple Syrup

- Violet Liqueur

- Candied Violets

- Violet Cookies

- Violet Infused Vinegar

- Violet Lemonade

We’re fond of just making tea with the violet blossoms, and it’s a really unique turquoise color. Add in a few drops of lemon juice and it quickly changes to a vibrant magenta.

It’s a great way to add magic to any tea party…

If you’re looking for ways to use violet greens, they’re often eaten in salads fresh, or as a cooked green.

I personally think the mucilage in the greens makes them unpalatable, except in small quantities. As you chew them, they become for lack of a better word, like mucus. It’s nasty.

Or at least it is to me, but to each his own.

These violet leaf recipes make good use of them and might suit your fancy if you like them fresh.

They’re also the medicinal portion of the plant, at least for most uses. While the flowers may draw your eye, you’ll want to make salves and tinctures mostly with the leaves.

The same mucilage that makes the leaves somewhat unpleasant to eat also makes them soothing to the throat and coughs, and great for topical issues.

Spring Foraging

Looking for more fun spring foraging guides?

- Foraging Morels

- Foraging Dryad’s Saddle

- Foraging Chickweed

- Foraging Ramps (Wild Leeks)

- Foraging Fiddleheads

- 60+ Dandelion Recipes

Hi, the roots can one also use the roots. Elize

From what I’ve read, the roots are the only part you can’t use.

I love your articles, they are so useful, interesting and informative. We have an abundance of violets and I never knew they were useful. Thanks.

You’re very welcome. We’re so glad you enjoy the articles. Be sure to keep us updated if you decide to use the violets.

I am surprised you did not mention that violets contain salicylic acid and are good pain-killers. I have violet tincture that I made from my backyard violets. In the mornings when I have leg pain, I take a dropper of the tincture and within a couple of minutes the pain is gone and I can walk without pain.

That’s a good point. Thank you for sharing.

Ashley thank you for blogging. I noticed this post last year and it made me really want to make violet jelly. I had to wait until this spring, but I DID it.!

Your instructions were easy to follow and clear. I collected 4 cups of flowers so I made 2 batches. My friends and neighbours are also enjoying it too😉

That’s wonderful! So glad you’re enjoying the jelly!

Thank you for this. Wild violets make me think of spring! I find them in the same riverflood zones where I harvest lady fern fiddleheads.

I have a question about the edibility of pansies versus violets. This post is the first source I have ever seen to recommend the eating of pansy leaves. Other sources suggest that with violets the leaves and flowers are edible, but with pansies and johnnies only the flowers are edible. Do you truly recommend eating the pansy leaves too? If so, is there a newer source or research that I have missed before that can vouch for pansy leaf edibility?

Many thanks, as always,

Jasmine

I found this article which talks about the toxicity. Apparently the leaves of pansies and johnnies are not typically eaten but the leaves are not known to be toxic. The seeds are toxic though so it’s possible that this may be the reason why it is not recommended to eat the leaves since they could be toxic as well.