Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Black walnuts (Juglans nigra) are an incredibly prolific wild nut species native to the United States. They’re easy to identify, and a satisfying way to add wild foraged calories to your winter larder.

Personally, I never get all that excited about foraging salad greens. There’s an incredible number of edible wild weeds out there, and while they’re often both tasty and refreshing, they’re never going to form the foundation of a wild foraged meal.

I get excited about wild fruits and berries that you can harvest and preserve in mass. Wild foraged grains that will fill your stomach and stock your pantry. Wild roots and tubers that will keep you satisfied.

You know, the things our ancestors ate from the land long before agriculture. And after that, the things the early modern settlers collected to supplement their crops and ensure survival in bad years.

Wild foraged nuts definitely fall into that category. Things like wild chestnuts that sustained peasants for generations in the form of chestnut flour. Acorns were a staple food in both the new world and Europe even in Roman times, as acorn flour, porridge, and more.

Beechnuts, butternuts, hazelnuts, hickory nuts…the list goes on.

Black walnuts are one of the most common wild nuts, especially in the northeast US. Only acorns are more common, but they take a lot more work in the form of leaching and processing.

Black walnuts are nutritious, prolific, easy to identify, and simple to harvest. Most years they produce so much that the squirrels and other animals can’t even put a dent in the crop, leaving most to rot on the ground.

While it’s true that they do take some effort to crack, there are simple tools for that. We are tool-using mammals after all. We’ve got this, right?

That, my friends, is basically free food just waiting for harvest.

What are Black Walnuts?

Black walnuts (Juglans nigra) are a deciduous tree in the walnut family, closely related to cultivated English walnuts (Juglans regia).

They grow on large trees that mature at over 100 feet tall, though unlike many other nut species they begin producing at a relatively early age (around 10 years old).

They’re native to Eastern North America, and their range extends well up into Canada. Since they’re hardy zone 3, they’re one of the most cold-tolerant nut species.

Black walnut trees also grow well into the Central US, and as far south as Northern Texas and the Florida panhandle.

Beyond that, they’re cultivated elsewhere, and animals (especially squirrels) are known to establish wild black walnut groves well outside of their native wild range.

What Do Black Walnuts Taste Like?

Now the million-dollar question…are black walnuts good eating?

That really depends on how they’re processed, and your taste buds.

Properly processed, black walnuts taste very similar to cultivated walnut varieties, but with a bit more “earthy” flavor and just slight hints of bitterness.

Regular walnuts already have some bitter notes, and you’ll taste that more distinctly if you eat the papery husks inside the shell and around the nut. Properly processed black walnuts have a bit more of that flavor, but only a bit.

Once the nuts ripen it’s essential to remove the outer green husk as soon as possible, otherwise, it’ll begin to break down and leach bitter/acrid flavors into the nuts inside. That’s where black walnuts get a bad reputation.

Some sources will tell you to skip the husking and just let the nuts sit until the husks break down on their own, but that’s a recipe for bitter walnuts that aren’t particularly pleasant. The same thing happens with butternut or English walnuts if you leave them sit in the outer green husk, even though both are otherwise sweet.

That said, some people just don’t like the flavor, and I’d bet many of those people also don’t much care for regular walnuts either.

Where to Find Black Walnuts

You can, of course, find black walnuts in the woods just about anywhere in their range.

They tolerate wet soils better than many tree species, so they’re often common in riparian zones.

Historically, they were valued for both their wood and their nuts, so they’re common on and around old homesteads.

In Vermont, there’s was a tradition of planting black walnut trees (or sugar maple trees) as a “marriage tree” when a new couple married and moved into their own homestead. This tradition persisted well into the 1970s.

A few years back, when I asked a neighbor if I could collect their fallen black walnuts. He’d planted it when he married his wife 50 years earlier, and she treasured the nut harvest every year. She’s no longer with us, and he was so happy that they’d be put to use.

Another excellent place to find black walnuts, and nut trees in general, is old cemeteries.

Why? Well, in the 1700s through the early 1900’s it was still common to bring a picnic and a party to the graveyard, to spend special holidays playing with the kids (so the grandparents could be there too). They weren’t always the silent, somber locations that they are today.

Intentionally planting long-lived nut trees ensured that they’d be a source of food for generations and that the family could stock the larder each year all while they visited their lost loved ones.

By today’s standards, it seems a little weird to harvest from old cemeteries, but I promise you that the people in actually buried in those old cemeteries would have expected nothing less. They were expecting the company each fall, and they had visitors doing just that for centuries before customs changed.

I’m sure they’d appreciate the company, plus a little dusting of their gravestones while you’re there, so they know they’re not forgotten.

Identifying Black Walnuts

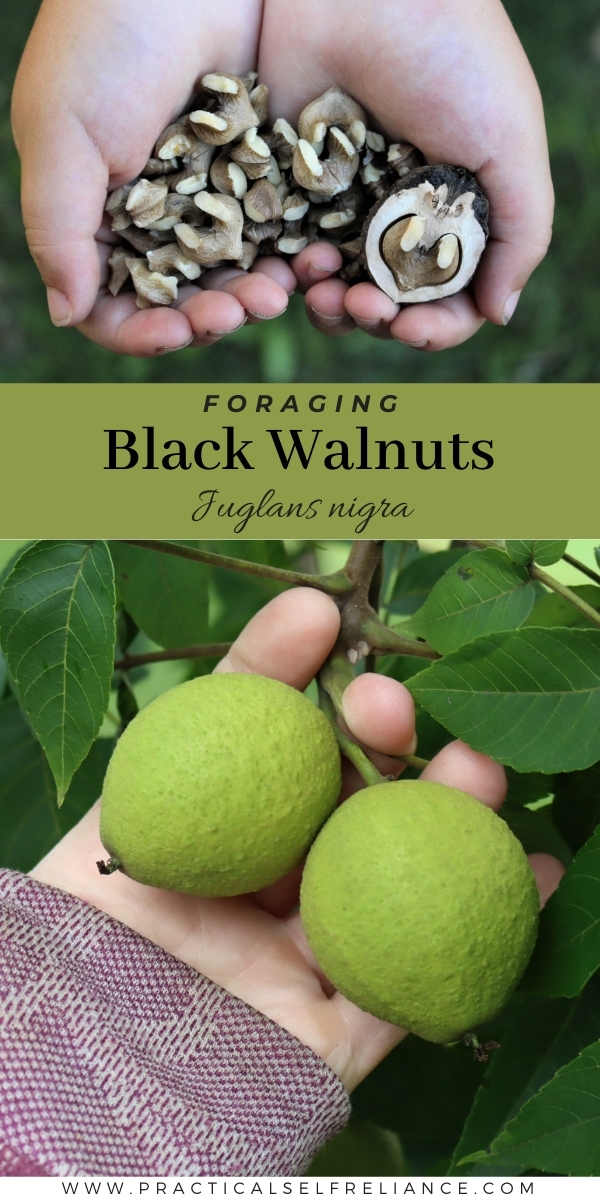

For the most part, black walnuts are easy to identify, especially when they’re in fruit. The bright green, round, tennis ball-sized nut husks hanging from the branches are a dead giveaway.

Butternut trees look quite similar but have different bark, and the nuts have a different shape.

All parts of the tree, except the edible nut meats, have a distinctive smell. It’s often described as “pungent” or “spicy,” and the leaves were used historically in seasoning.

There’s a Worcestershire-like sauce that was seasoned with black walnut leaves in colonial times.

Personally, I think the leaves smell a bit like a cross between bay leaves and citrus, and that scent will be there even if the trees are not in fruit.

Black walnut leaves are pinnately compound and alternately arranged on the stem.

That means that each “leaf” is actually a long strand of many leaves that are attached at a single point on the branch. When black walnuts drop their leaves in the autumn, they drop the whole leaf stalk as one piece. Each one has 15 to 23 “leaflets” attached.

Each leaflet has a rounded base and a pointed tip and tends to be the widest in the middle. The edges are serrated and the underside is ever so slightly hairy on the underside.

One thing I’ve noticed with black walnut leaflets is that they tend to be twisted a bit at the attachment site. If you hold a compound leaf with the tip pointed down at the ground, the leaflets will be twisted so that their leaf surface points up at the sky.

This is just my observation in the black walnut trees I’ve seen, and it may not be universal. It does look pretty neat visually when you’re holding a leaf stalk.

As the nuts ripen, the leaves will already be turning colors in the autumn. They go from a deep green to a bright, almost fluorescent yellow color seemingly overnight.

I can often pick out the bright yellow black walnut tree tops driving down the highway during foliage season, especially given their distinctive compound leaves.

Some sources will tell you that black walnuts don’t have terminal leaflets, where as butternuts do, and they use that for identification. That’s not technically correct…

Black walnut terminal leaflets are often present and completely normal. Sometimes, however, they’re small, deformed, or fall off during the season. In a quick survey of leaflets on a dozen trees, I found terminal leaflets on about half of the compound leaves on any given tree.

The pictures below both come from the same black walnut tree, on the same branch even.

Black walnut tree bark is grey-black in color, and deeply furrowed.

It’s much less distinctive than butternut bark, which has deeper furrows and a unique diamond shape pattern. The raised portions on a butternut are almost silver and leaving near black diamond-shaped indentions.

Black walnut bark, on the other hand, is a good bit less dramatic.

Black Walnut Look-Alikes

There are a number of trees across the black walnut’s natural range that have rough bark and pinnately compound leaves. Ash trees, for example, are quite common.

A close look though, and they’re quite different. And obviously, they don’t produce nuts.

There is another nut tree that does look quite similar though, and that’s butternuts.

What’s the Difference Between Black Walnuts and Butternuts?

Butternut trees are very similar to black walnut trees, but there are a few notable differences.

- Black walnut nuts are roughly round, whereas butternut are oval or barrel-shaped.

- Black walnut trees have grey ridge bark with small-ish diamond shapes, while butternut have deep furrows and large diamonds in their bark. The raised portion is smooth and silver, while the shallow diamond shape is dark and nearly black. This is only true of mature trees, and young trees of both species have variable bark.

- Black walnuts have a leaf scar that looks like a money face, while butternut have a monkey face with a mustache (a furry portion above).

- Black walnuts are sometimes missing the terminal leaflet, but not always. Butternuts usually have terminal leaflets.

I know this doesn’t sound like a whole lot of differences, and it’s not. The nuts themself are quite different, but beyond that, the differences are pretty tricky to pick out unless you’ve been looking at them all day.

I have a really detailed guide to foraging butternuts (Juglans cinerea), including identification that has a lot of great pictures.

Beyond that, the University of Perdue has a botanical guide with very detailed photos of every part of each tree, including super closeups of the leaf scars to help you ID them in the off-season.

Husking Black Walnuts

The first time I showed these to a friend they said, “Those aren’t black walnuts, they’re green walnuts!”

I suppose that’s true, so of.

Black walnuts have a green fleshy outer husk around the actual nut shell, and that part is incredibly perishable. It’s important to remove it as soon as possible after harvesting so that it doesn’t begin to spoil and leech bitter flavors through the shell into the nut.

The husk itself is spongy, and a lot like a grapefruit peel. When they’re fully ripe it’s easy to just peel it off, more or less exactly like peeling a citrus fruit. (When they’re a bit underripe it tends to cling tenaciously to the nut shell, making it tricky to remove.)

To tell when the nuts are fully ripe, give them a bit of a squeeze. If the husk gives to gentle pressure, like a grapefruit, then it’s ready. If the husk feels really firm then it’s not ready yet.

Either way, remove the husks as soon as you can after harvest. The husks are staining and were used as a dye and ink traditionally, so it’s best if you wear gloves. Save the husks to make a black walnut tincture, which is an alcohol extract of the husks that are used as a natural de-wormer and iodine supplement.

(Occasionally the husks can also cause allergic reactions, so that’s another reason to wear gloves even if you’re not worried about staining. I don’t have a reaction to them, and never have, so I often just quickly peel them, rinsing my hands in a bucket of water in between each nut to prevent staining.)

How Long Do Black Walnuts Last in the Shell?

Once you’ve removed the husks from the black walnuts they should be dried for a few weeks before storage. Leave them in a well-ventilated area, ideally in a single layer so they can fully dry.

When husked and dried, black walnuts will store for an extended period at room temperature without spoiling. They’ll usually be good if left untracked for about a year before they start to degrade.

Once cracked, the oils in the nuts are susceptible to oxidation and they can go rancid, so keep them in the shell until you’re ready to use them.

How to Crack Black Walnuts

Black walnuts are notoriously difficult to crack, and they’re known to be one of the very hardest nuts. Small handheld crackers like the ones usually found in nut bowls at holiday parties just won’t do the trick.

You’ll need something with a bit of lever action or a slow tension vise that applies steady mechanical pressure.

I have a really nice lever-action nutcracker that’s mounted to a piece of wood and it works wonderfully.

Lacking a nutcracker, some people say they crack them by driving their car over them. I’ve tried that, and it didn’t work for me at all…wheels just rolled right over.

What does work is putting the nuts in a pillowcase and hitting them with a hammer. The pillowcase keeps the nutshell fragments from flying everywhere on impact.

The downside of that method is that the nutmeats themselves are often pulverized into teeny tiny pieces and all mixed in with shell fragments. You’ll rarely have a full-sized nut with that method.

Looking for a better method?

I’ve found that if you leave the nuts to dry a good long time they’ll often develop a crack along the seam that separates the two halves. I slip my pocket knife in that crack and the nuts pop right in half.

That’s definitely the easy way!

I think patience is a better option, as they get easier to crack as they dry.

The shell becomes more brittle, nut inside shrinks back as it cures, and they often develop a “crack” on their own.

It’s also a lot easier to pull the nut out at that point since the nutmeats have shrunk away from the shell a bit more.

This is the only method I’ve found that allows me to get big pieces of black walnut once they’re cracked. Even the nutcracker tends to crush the nut inside a bit, and makes a lot of small shell fragments.

Once the nuts are halved, just pry the nut meat out and you’ll have some good-sized pieces.

This won’t work with all black walnuts, but if you’re patient and get them good and dry a good portion will split on their own.

Black Walnut Recipes

After all that work, now what? How do you use black walnuts?

Well, for the most part, they can be used anywhere you’d use walnuts. I think they’re great in chocolate chip cookies, and they make a fine pie.

Taste them first, of course, as if you don’t like black walnuts, you’re not likely to like anything made with them.

- Black Walnut Butter ~ Woodland Foods

- Black Walnut Sandwich Cookies ~ Land O’Lakes

- Black Walnut Ice Cream ~ Hunter Angler Gardener Cook

- Black Walnut Pesto ~ Forager Chef

- Black Walnut Pie ~ Learning and Yearning

Unripe Black Walnuts (Green Walnuts)

Beyond ripe walnuts, which are husked then shelled, there are also ways to use immature green walnuts early on in the summer. At this stage, they’re left in the shell and husk and used whole.

The husk adds amazing spicy/citrus flavor, and the nut itself inside hasn’t solidified yet. It’ll basically dissolve into recipes, adding richness to complement the spicy flavor of the husk.

Harvesting green walnuts happen in the summer, usually around the solstice, and is steeped in legend and folklore.

If you’re curious and you happen to find a black walnut tree early in the season, I have a detailed guide with plenty of green walnut recipes (as well as harvesting tips and folklore).

Where to Buy Black Walnuts

Very occasionally I’ve seen black walnuts along with other nuts in the baking aisle of the grocery store. For the most part, they’re hard to come by unless you harvest them yourself. (Or know someone who does.)

Sam Thayer, my favorite foraging author, also runs a foraged food company that sells black walnuts among other things. You can order them through his site, Forager’s Harvest.

Foraging Guides

Looking for more seasonal foraging guides?

- Edible Wild Mushrooms for Beginners

- Foraging Chokecherries

- Foraging Serviceberries

- Foraging Autumn Olive

- Foraging Nannyberries

- Foraging Ramps (Wild Leeks)

Thank you for such a detailed explanation about black walnuts! We had a hickory tree in our front yard as a child but no one knew exactly what to do with them. Now they are everywhere around me since I live in a semi rural area in Missouri. I’m going to make the effort to forage, dry and crack them for the winter. Thanks again! 😊

You’re quite welcome!

Thanks for your helpful post, and other posts that I have read as well! Have you had black walnuts with a thin orangish center inside the meat? If so, is this normal and safe to eat?

Thank you!

I haven’t experienced that to be honest. If you’re unsure about it, I would discard them.

Thanks for your article! keep them coming! We have recently harvested some here in PA and we put them in the driveway to get the hulls off but then later after they dry we crack them. Or we intend to! Lol, usually they lie around for awile but we have good intentions. . We have also made Nocino!

You’re very welcome. I can certainly understand those good intentions.

Thanks for the post, Ashley. I harvest Southern California black walnuts. Once the husks are dry and falling off, I clean them up as much as possible, stand them on the bottom point so that I can see the crack across the top and down the sides and hit them with a hammer. I can get most of them to split in half that way. For people who don’t trust their aim, I recommend holding the nut with pliers.

You’re welcome. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for this article. I have a passion for foraging wild edibles and every fall I am deluged with an abundance of black walnuts and hickory nuts. I trip on them, they bonk me on the head, they cover my driveway, yard, the edges of my woods, and my street.

It annoys me to no end every year, because I developed a tree nut allergy 10 years ago. The squirrels are quite happy, though!

I am so glad you enjoyed the article. Sorry you aren’t able to enjoy the nuts.

Where I live they aren’t that common anymore and the butter nuts even less so. Most people find them to be too much “clean up” in the fall and would be too lazy to put any effort into harvesting them, so in my town they get cut down every year or if you have them on your property tree pirates steal them for the very valuable lumber from them.. Another method of cracking is put them in your driveway and run them over with your car. I watched crows roll them out into a roadway and sit and wait for cars to run them over so they could eat the nut meat. They relished them.

I love them in cakes, Walmart sells them every year in their nut section and baking section.

Really enjoyed that post Ashley- Your style and flair made for a pleasurable informed read. I catch you occasionally from my now home Australia, so that report brought back childhood memories in California. I was fond of the beautiful grain and colour, hard and dense-ness, and distinct smell of the wood. Considered the nut too difficult and small, especially when compared to the English nut. Great tips and all around info. Cheers, Mark

Thank you. So glad you enjoyed the post.

Thank you for this timely and fact full post.

Have you smelled the walnuts in their fresh husk. I love their perfumed scent.

You’re very welcome. So glad you enjoyed the post. They definitely do have a distinct scent.

To remove the green husk I use the flat side of a hammer. lay the nut on a cider block & strike firmly. When cracking dry nuts I strike them with the proper side of the hammer. Each nut has a top & bottom. The top is the end that was attached to the tree. Strike that end firmly. If the shells are very dry the nut will come out in halves or quarters. Drying them out well is the key.

Ashley – Thanks for the thorough, informative article! Just husked my 1st black walnuts today (5 gal bucket = maybe a 1/2 gallon of shelled nuts). We have more than 30 mature trees, so I guess it’s about time to do something with them. Much appreciated.

Wonderful, so glad you’re putting them to use!

I have used an old hand crank corn sheller, big floor model, to remove the dried husks from the black walnuts which I save to feed our neighboring squirrels in the winter. Have you ever tried using a sheller to dehusk the walnuts when they are still yellow but ready? I wonder how that would work.