Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Bunchberries (Cornus canadensis) are an easy to identify wild edible berry with a number of uses (beyond fresh eating). Their sweet flavor, combined with a high pectin content makes them the perfect addition to homemade jams.

Bunch berries were one of the first edible wild fruits I learned to identify, after the common everyday ones like raspberries and blackberries. I was out walking with a friend, and he spotted a colony of low-growing creeping dogwood (as the parent plants are sometimes known), and actually started dancing with excitement.

He was that kinda guy, and though he didn’t know that many wild edibles, the ones he did know brought him immeasurable joy, and he couldn’t help but share this one with me. I didn’t consider myself a forager (yet), and eating a random berry from the forest floor on his say-so seemed a little suspect.

I watched him run from bunch to bunch, harvesting them by the handful and munching them with glee. He was just so darned enthusiastic about these little fruits, I couldn’t help but join him.

On first taste, they’re mild and unassuming, a bit gelatinous, and quite sweet. They don’t honestly taste like a whole lot, except mild sweetness with a thick, creamy texture…like a pudding you forgot to flavor.

These days, I do forage regularly, but I tend to go after intensely flavored fruits.

I love astringent chokecherries and chokeberries, tart wild gooseberries and rose hips, and even tannic wild black currants. They’re a bit like a kick in the mouth, but they remind your you’re alive (and that nature has a lot more character than mild grocery store fruits).

The thing is, now that I’m foraging with my kids, I know that those “kick in the mouth” type berries don’t tend to please everyone. Just the opposite, in fact.

Sometimes you just want mild sweetness, harvested en masse at an accessible-height just a few inches off the ground.

They quickly became a favorite of my two-year-old son, and his pudgy little toddler hands couldn’t harvest them fast enough. I’ll put him to work on a patch of those carpeting a pine forest, and then I’ll go to work harvesting the more intensely flavored rowanberries growing above.

What are Bunchberries?

Bunchberries or “Bunch Berries” (Cornus canadensis) are a fruiting plant in the Dogwood family. They’re also known as Canadian Bunchberry, Bunchberry Dogwood, Dwarf Dogwood, Dogwood Bunchberry, Creeping Dogwood, Pudding Berry, Quatre-Temps, Crackerberry, Canadia Dwarf Cornel, or just plain Dwarf Cornel.

They grow in what’s known as “clonal colonies” where underground runners spread, and then they sprout up as what look like individual plants. This colony growth habit means they tend to grow in dense mats on the forest floor.

Where to Find Bunchberry

Bunch berries tend to grow in dense colonies on the forest floor, beneath pines and in areas with acidic soil. They’re often found in the shade deep in the woods, or beside trails, near wild blueberries and rowanberries.

They’re native all over the world, anywhere that has cool, moist acidic soils.

Their range includes Asia (Japan, Korea, China), Russia, and Northern Europe, as well as boreal forests in Canada and Greenland. In the US, they can be found in the northern states down to the middle latitudes, as well as down into the high-altitude portions of Colorado and New Mexico.

Identifying Bunchberry

Bunchberries are perennial plants that tend to grow in clusters or colonies, but they can also be found singally.

Early in the season, bunchberries emerge from the soil as a small, erect herbaceous green plant.

Bunchberry Leaves

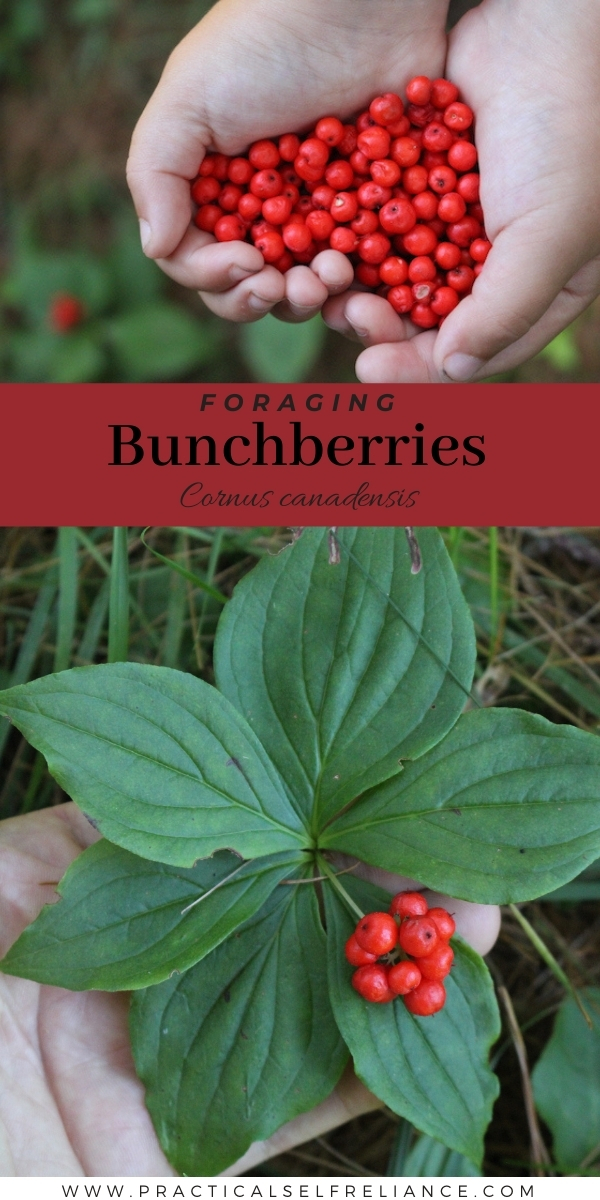

Early in the season, the plants start off as a whorl of 4 to 6 leaves on a single stem. Each leaf is has an elongated oval shape with a tipped point (almost diamond-shaped, but without the side points).

The leaves are usually 1 1/2 to 3 inches long, with smooth edges (un-toothed) and they taper to a point at both ends.

The stems come up singly from each rhizome in the colony and are unbranched until they reach the whorl of leaves.

A bit later on in the season, a single distinctive white flower will appear above the leaf cluster.

Bunchberry Flowers

The flowers themselves have 4 petals, and each petal tapers to a point, much like the leaves.

If you look closely, you’ll see that the flower isn’t truly a “single” flower, though it does have the appearance of one. The petals are actually around a cluster of ovaries which if pollinated, will each form a single berry in the bunch (thus, bunchberries).

This is more apparent after pollination after the petals have fallen off.

The flowers appear in early summer or late spring, and the berries ripen from mid to late summer, occasionally in early autumn in far northern regions.

Bunchberry Fruit

The fruit production can vary based on pollination, and sometimes clustes or “bunches” of bunch berries are bigger than others. I tend to see them in clusters of 10-12 individual berries on a plant, but occasionally there are a few more…or just one or two per “bunch.”

They’re ripe when the fruit are bright red in color, and they’re a pale green as they develop.

Earlier in the season, the flowers stood on a stem about 1 to 2” above the whorl of leaves, and as the berries develop they’ll stay above the whorl of leaves.

When they swell, they can make the plant droop over with their weight, but sometimes they’ll stay erect and support the berries just fine.

Either way, you’re looking for a cluster of red berries, all tightly packed together above a whorl of distinctive pointed oval leaves with parallel veins.

Bunchberry Look Alikes

There are plenty of other small red berries in the woods, and some of them are toxic. I’d argue that the leaves and growth habits are incredibly distinctive, and while you will see plenty of red berries…you won’t see any that look all that much like bunchberry plants.

That said, I’m always amazed at how optimistically foragers see the plants they want to find…even in look likes that look nothing alike.

Be sure to watch out for red baneberry, a poisonous fruit that also has clusters of red berries on a low-growing plant. The plant tends to be much larger, and the leaves look nothing alike. The berries themselves are on elongated spikes, rather than small rounded clusters. Still, they’re ripe at the same time and occupy many of the same niches ecologically.

Rowanberries look very similar to bunchberries, but they grow in clusters on trees. They do happen to grow in the same environment, and you’ll often find bunchberries growing under rowanberries (aka. mountain ash trees).

When the rowanberries fall, they can land among the bunchberries on the forest floor and be collected accidentally. They are edible, but they have a very different taste that many people don’t like.

Also, be sure to watch out for red fruited nightshade species, which also grow low to the ground on occasion.

They’re not in clusters, and the fruits aren’t all that similar…but it’s possible you could collect them by accident if you’re not paying attention.

They’re also toxic, and should be avoided.

Harvesting Bunchberries

Once you’ve identified bunchberries, harvesting is pretty straightforward. Reach down and grab a cluster of fruits and give a gentle tug.

They’ll easily pull away from the plant and you’ll have 10-12 in your hand in a single motion. If you have tiny toddler hands, you might not get them all as they pop out and fly everywhere…be sure to grab the whole bundle if you want to keep them.

In a colony of bunchberries, it’s easy to collect them en masse in just a few minutes. You can collect a pint in roughly 5 minutes with little effort, if the stand is productive.

While we’re often able to collect plenty, my kids tend to eat them all as fast as they can pick them. It actually took a lot of work (and some bribery) to get them to pick a handful to let me photograph, rather than going from plant to mouth instantly.

How to Use Bunchberries

If you are able to collect bunchberries to bring home, without your kids eating them all in the field, then you can use them to make traditional jams and puddings.

They’re incredibly high in pectin, and they have a soft, sweet, pulpy fruit around small hard seeds. It’s not easy to separate the fruit from the seeds without cooking, and if you want to remove the seeds you’ll need to cook them and then press them through a fine mesh sieve.

I think it’s just easier to cook them in a sachet of cheesecloth and let the pectin and sweetness infuse into the cooking liquid, and then remove the whole sachet. I do something similar when I’m using citrus seeds for pectin to make jams and jellies.

The actual amount you need to set a jam will depend on the pectin content of your particular bunchberries, as well as the pectin content and sugar level of your fruit. It’s tricky…and you’ll have to experiment here.

There is a little big of guidance in this article from a writer in Alaska that used bunchberries to help set a jam made from thimbleberries, but even there, she notes that it’s impossible to give a specific amount.

Beyond setting jams and making puddings, they can also be dehydrated into “bunchberry raisins.” The flavor is sweet and mild, as you might expect from the taste of the fruit fresh.

As raisins, they are good in trail mix, granola, and oatmeal.

Wild Fruit Foraging Guides

There’s an unbelievable variety of edible wild fruits and berries to be found! As always, watch out for poisonous berries and look likes!

- Foraging Chokecherries

- Foraging Autumn Olive

- Foraging Solomon’s Plume

- Foraging Aronia

- Foraging Serviceberries

Foraging Guides

Looking for a few more foraging guides to keep you in the woods this year?

- Foraging Green Walnuts

- Foraging Ramps (Wild Leeks)

- 40+ Wild Plants You Can Make Into Flour

- Spring Foraging – 20+ Wild Spring Edible Plants

- Winter Foraging – 50+ Plants to Harvest in the Snow

Can’t express my gratitude enough! ✨

How do you typically go about making bunchberry raisins? I love that idea! They would keep much better than the awkward cup shoved on the fridge that my family usually does.

You would just need to dehydrate them.

It’s worth pointing out that not all dogwood berries are edible! CORNUS CANADENSIS is edible, but CORNUS FLORIDA’s berries are poisonous. Down south, we don’t have creeping dogwood, but we have flowering dogwood (a small tree) galore. Don’t assume the red berries on those little trees are edible; they’re deadly poisonous to humans. Leave those ones for the birds!