Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

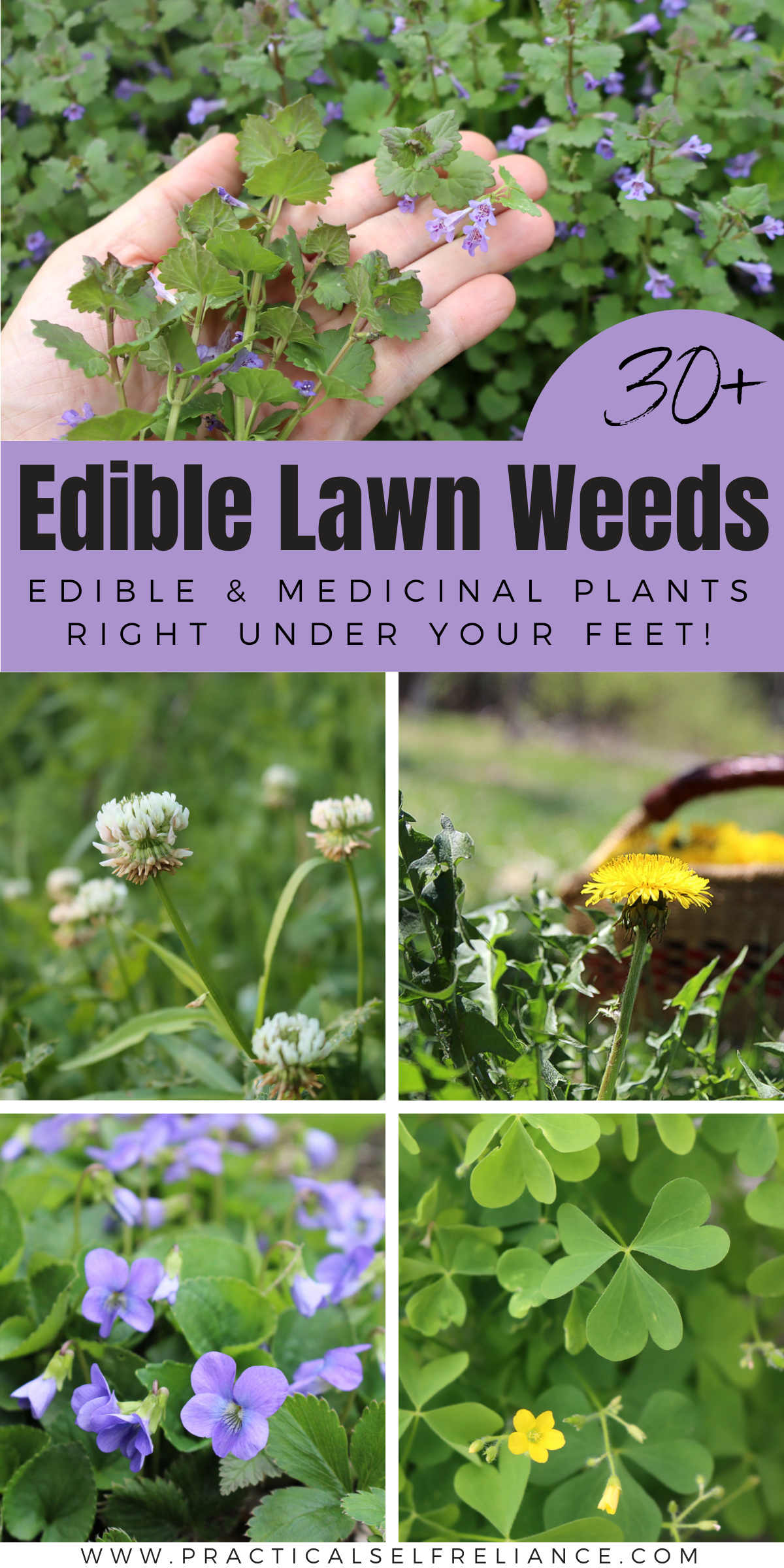

Edible lawn weeds are easy to find in suburban backyards, parks, and anywhere a lawn mower travels. These fun little plants know how to thrive, competing against the grass and staying low, ducked beneath the lawnmower’s blade.

All of the wild lawn weeds listed here are edible, and many are medicinal as well.

There are literally hundreds (if not thousands) of edible wild weeds out there, and honestly, it can be a bit overwhelming and intimidating when you start trying to learn them all.

But the trick is, you don’t have to learn them all. You don’t have to trek through the woods or hike mountains seeking out any particular plant. Wild plants are everywhere, and wild weeds are especially prolific, thriving where other plants can’t get a foothold.

When you’re just getting started, one of the best things you can do is look right beneath your feet.

While my little ones play out on the lawn, or at a park, or even in downtown in front of the ice cream shop, I’ve got plenty of time to look at the world right beneath my feet.

If you look closely, you’ll notice that there’s grass, of course, but there’s also a lot that’s not grass. What is all that other stuff?

Believe it or not, most wild weeds that grow in lawns are either edible, or medicinal, or both.

They’ve evolved right alongside humans, tolerating mowing, grazing, and soil compaction, and we’ve found wonderful ways to use them over millennia. They’re right there, just waiting to be rediscovered.

My daughter’s picked up on the game and now stops mid-stride during water balloon battles to pluck new strange lawn flowers for me to ID. She knows, better than anything, how to make her mama smile.

Weeds with tiny purple flowers almost always mean edible and medicinal on a lawn.

Many of them are simple things that everyone knows and sees almost every day…things like clover, dandelions, and plantain. They’re easy to see in just about any grassy space, and the trick is knowing that they’re edible, tasty, useful, and potentially even medicinal.

Others take a bit more work, and while they might be just as common, they’re not readily in our modern day-to-day vocabulary. Things like speedwell and heal all, which as their names suggest, were popular medicinals back in the day. Others like Ale Hoof (or ground ivy), which were used to make beer just 100 years ago.

Some are even escaped garden plants, that establish themselves in lawns and grow like weeds without a care in the world. Wild Asparagus isn’t really wild, it’s “feral” and escaped from somebody’s garden, with the seeds carried by birds for a few hundred feet (or a few hundred miles).

It’ll pop up anywhere that’s not mowed too often, and is fond of growing right around mailboxes and street signs, where it won’t get mowed down except for occasionally when the weed whacker comes out.

Other garden plants will establish themselves right alongside the wild weeds, and anyone that’s grown mint knows how weedy this plant can be. You can’t really control mint, and wild mint is one of the most vigorous plants alive.

Truly wild mint isn’t nearly as tasty as the garden varieties that have been selected for flavor, but no worries, those garden varieties are just as weedy. This stem of chocolate mint (or at least a very similar wild variety) is growing in the grass at the base of one of our cherry trees, battling it out with speedwell (tiny blue flowers) and dandelion.

I didn’t plant it, but it’s delicious, just the same.

I spent much of this spring and early summer combing the grass, watching new plant life emerge. Many of them are plants I’ve seen dozens of times in foraging books, but I just had no idea they were so close at hand.

All of them are there, right under your feet, once you learn to see them.

While just there are literally hundreds of weeds that could grow on your lawn, I’m going to try to limit it to just the things that can handle mowing/grazing at least semi-regularly (every 2-3 weeks or so) up to regular mowing (every week, or multiple times per week).

If you mow less regularly, like every month or two, or you get into more old field-type weed species like goldenrod, chickory, and melilot, but I’ll save those for another time.

Not all of these will necessarily reach full form in a lawn, but things like mullein can hunker down and stay below the lawnmower for many years…waiting for a year of neglect to send up a tall flower stalk.

List of Edible Lawn Weeds

Here’s my list thus far, and I invite you to scour your lawn with me, and we’ll see what we can find together this summer:

- Bugleweed (Ajuga sp.)

- Chickweed (Stellaria media)

- Chives (Allium schoenoprasum)

- Chufa (Cyperus esculentus)

- Cleavers/Bedstraw (Galium sp.)

- Clover (Trifolium sp.)

- Crabgrass (Digitaria sp.)

- Creeping Thyme (Thymus serpyllum)

- Dandelion (Taraxacum sp.)

- Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea)

- Evening Primrose (Oenothera sp.)

- Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule)

- Horsetail (Equisetum sp.)

- Mullein (Verbascum sp.)

- Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

- Plantain (Plantago sp.)

- Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium purpureum)

- Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

- Prosso Millet (Panicum miliaceum)

- Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

- Ryegrass (Elymus canadensis)

- Sedge (Cyperaceae sp.)

- Self Heal (Prunella vulgaris)

- Speedwell (Veronica sp.)

- St. Johns Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

- Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

- Violets (Viola sp.)

- Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

- Wild Mint (Mentha sp.)

- Wild Oat (Avena sp.)

- Wild Strawberry (Fragaria sp.)

- Wood Sorrel (Oxalis sp.)

- Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

I’ll take you through each of these edible lawn weeds, one by one.

Bugleweed (Ajuga sp.)

Most gardeners either know bugleweed as a charming cultivated groundcover or an invasive weed. All bugleweeds are perennial herbaceous herbs in the mint or Lamiaceae family. Like many of their minty cousins, they’re versatile herbs that offer culinary and medicinal value. They’re generally quite easy to find and have a habit of carpeting moist lawns, meadows, forest edges, and other spaces with moist, humusy soil.

I love harvesting bugleweed’s vibrant purple flowers in the spring to decorate cakes and add color to salads. The young leaves are also enjoyable fresh. As they grow, the leaves become tougher and bitter, so I usually reserve the older leaves for medicinal use or as a cooked potherb.

Bugleweed has a long history as a medicinal herb. Traditionally, it was often called carpenter’s weed and is great for staunching bleeding from minor cuts and wounds. Modern studies have also indicated that bugleweed may be a helpful plant for regulating hormones, particularly in women. Use caution with bugleweed, especially in large amounts. Though it’s a handy herb, it may interact with certain diabetes and heart medications.

Depending on your climate, bugleweed may be evergreen or semi-evergreen. You may spot it forming colonies of shiny dark green leaves in basal rosettes year round. In the spring, watch for it to send up eye-catching spikes covered with whorls of bugle-shaped violet blooms.

Chickweed (Stellaria media)

In the United States, nettles have earned the crown as the king of spring greens among foragers and herbalists. Chickweed doesn’t seem to get as much praise, but in my opinion, it’s the queen. Few other wild greens are as succulent and refreshing as the tasty leaves and stems of chickweed.

Chickweed is easy to find and recognize, too. It’s a low-growing, sprawling herb that tends to form tangled mats covering large ground sections. It has oval leaves with pointed tips that form in pairs along the stem and tell-tale little, white, star-like blooms. Each flower has five petals, but each has a dip in the center, making them look like ten petals until you look closely.

When the weather is still cool, and patches of snow are still clinging to the ground, I often begin finding chickweed in lawns, gardens, woodland openings, trailsides, and waste places. Its tender stems and leaves help make up some of our first spring salads. I also like using them in pesto and on sandwiches.

Chickweed is among the classic spring tonic herbs. It’s loaded with essential vitamins and minerals like A, D, B complex, C, calcium, potassium, phosphorus, zinc, manganese, sodium, copper, iron and silica. It’s also a go-to herb for treating digestive issues and skin conditions like eczema, acne, and psoriasis.

We use it in spring salads, but I also make chickweed tincture and chickweed salve.

Chives (Allium schoenoprasum)

Wild chives are another of my favorite spring finds. What they lack in bulk, they make up for in incredible flavor. If you’ve ever grown or used domestic chives, you’ll probably recognize these; they’re nearly identical. Wild chives have the same hollow, tube-like leaves, pink blossom, and onion-like fragrance.

You can use wild chives the same way you would use domesticated chives. They make tasty additions to breads, bagels, dips, herbal butter, and other savory dishes. I also enjoy infusing the leaves and blossoms in vinegar or oil to make sauces and dressings later.

Today, we tend to mostly use chives in a culinary sense, but historically, people used them as medicinal herbs, often for treating digestive complaints and parasites. New research has shown that, like many members of the Allium or Onion family, wild chives have a multitude of benefits. They’re a good source of vitamin K, essential for bone health and blood clotting, are rich in antioxidants, and may have some anticancer effects.

Wild chives are native to North America and some patches along river banks and in woodland meadows where they likely are naturally occurring. I also find them in areas where they have naturalized or escaped cultivation, such as agricultural fields, old homesites, and vacant lots.

Chufa or Yellow Nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus)

Also called tiger nuts or yellow nutsedge, chufa is one of the oldest cultivated plants. Archeologists have found chufa roots at Wadi Kubbaniya, a late paleolithic site in upper Egypt dating back to around 16,000 BC. This sedge spreads readily and today occurs across much of the world. Here in the United States, it’s considered invasive and tends to quickly colonize wet areas.

You may spot chufa growing in wet areas of your lawn, garden, or fields. Thankfully, chufa is a fairly handy plant to have around. It produces edible tubers that taste remarkably like hazelnuts. They’re delicious raw from the ground, roasted, dried, or boiled. They’re a bit sweeter after drying. You can grind them into flour for baking or make a beverage. In Spain, they’re used for horchata.

I don’t generally use them as medicinal herbs, but some studies have also found that chufa tubers may help with digestion. Additionally, researchers have found that they have potential antibacterial, antioxidant, and insecticidal activities.

From a distance, chufa looks a bit like grass, but unlike true grasses, its smooth, glossy green leaves have a v-shaped cross-section. When in flower, its clusters of golden yellow-brown spikelets can help you pick it out. When you dig the plants, you’ll find their small brown tubers growing along the roots.

Cleavers/Bedstraw (Galium sp.)

Depending on who you talk to, cleavers or bedstraw may be a nuisance weed or essential herb. This genus includes over 600 species of perennial and annual herbaceous weeds that tend to be rough and hairy and have sticky little seeds that grab onto clothing and fur. In some cases, cleavers can be annoying for farmers, climbing onto crops and generally being ignored by pasturing livestock like cattle. However, cleavers species have some nicer attributes, too.

The cleavers species I most commonly find is often just called cleavers or catchweed bedstraw (Gallium aparine). Despite its rough texture, it makes a surprisingly decent potherb if you gather it before the fruits appear. Some folks also gather the fruit, roasting them as a coffee substitute or using them for tea. Medicinally, herbalists generally use the whole plant in teas and tinctures to help treat UTIs and bladder infections. It may also help with external issues like psoriasis.

Possibly the most notable cleavers species is sweet woodruff (Galium odoratum). Its pleasant fragrance and flavor has led to its use in flavoring sweets as well as May wine, a drink common in Germany to celebrate the coming spring. Historically, people also used it to stuff mattresses and to keep clothing smelling fresh.

Cleavers are fairly distinct and easy to identify. Look for sticky, sprawling vines with whorls of 6 to 8 leaves along their length. They aren’t picky about their habitat, but they do prefer that their leaves get a little sun. Keep an eye out for cleavers in woodland openings, croplands, pastures, lawns, ditches, beaches, and clearings.

Clover (Trifolium sp.)

Many people recognize clover or at least a species or two, but fewer realize how many benefits it offers. Along with being edible and medicinal, clovers are great for pollinators and gardens. Regenerative farmers often use this important plant as a cover crop as it has the ability to pull nitrogen from the air and add it to the soil.

As a forager, I love using the sweet blossoms for salads, baked goods, and teas. The leaves are good, too, especially when they’re young. Clovers are often used medicinally to boost the immune system, while red clover (Trifolium pratense), in particular, is among the most potent “women’s herbs.” It’s helpful for treating menopause symptoms, hormone issues, heavy menstruation, and more.

Clovers are all herbaceous weeds that often grow to around 12 inches tall. Depending on the species, they may be annual, biennial, or perennial, but all feature the trifoliate leaves that give the genus its name, Trifolium. They feature dense red, pink, white, or yellow flower heads. Generally, clovers grow best in openings. Look for them in fields, pastures, gardens, roadsides, forest clearings, waste areas, and pathways.

Worldwide, there are over 300 species of clover. Generally, I find imported white clover (Trifolium repens) and red clover (Trifolium pratense) growing as lawn weeds where I live. I focus on harvesting these and other naturalized and cultivated species like crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum). We also have about ten native clovers that grow in the United States. Unfortunately, several of these, like running buffalo clover (Trifolium stoloniferum), are now endangered.

Crabgrass (Digitaria sp.)

Many lawn-owning Americans spend a lot of time fighting this weed. Oddly enough, our ancestors probably intentionally introduced crabgrass to the United States as a drought-hardy grain and forage crop for livestock. It was a common crop long before that, too. Archeologists believe that in the Stone Age, humans were cultivating crabgrass in Switzerland, and crabgrass has been an important food in parts of India and Africa since prehistoric times.

Crabgrass seeds are what I forage for and what most early humans were after. Like other grains, you can grind them into flour, cook them as porridge, or ferment them to make beer. Today, crabgrass is rarely used medicinally, though there are some historical records of medicinal use and some modern research that suggests the different species may have anti-ulcer, anti-helminthic, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and antidepressant activity.

One reason crabgrass is such a prevalent lawn weed is that it thrives in open, sunny areas with poor soil. Look for it growing in lawns, waste places, fields, old gardens, and roadsides.

To identify crabgrass, watch for low-growing mats of grass-like leaves with rolled stems that root at the nodes. It produces finger-like spikes of seedheads that form from different points at the top of the stem.

Creeping Thyme (Thymus serpyllum)

This fragrant herb is one of the most beautiful weeds on this list! It’s a wonderful, low-growing, creeping, evergreen perennial with an abundance of stunning clusters of tube-shaped pinkish-purple flowers. Though native to Northern Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa, you can sometimes find it growing lawns and gardens in the United States. Gardeners and landscapers often plant creeping thyme as a low-maintenance groundcover.

Creeping thyme isn’t the same as the common thyme (Thymus vulgaris) we usually use in our kitchens. However, both its leaves and flowers are edible and fragrant. One of the main reasons it isn’t used in cooking is that the flavor is somewhat inconsistent. It’s a fun herb to use and experiment with, but don’t expect it to taste exactly like the thyme on your shelf.

Traditionally, creeping thyme was a common medicinal herb. It has antibacterial properties, and people have used it as an antiseptic. Some herbalists also use it for IBS symptoms and coughs. For coughs, I like to use it as tea with honey or as a simple thyme tincture.

Dandelion (Taraxacum sp.)

Dandelion may be the most familiar weed in the United States. Most children can pick out its bright yellow blooms. Despite this, I’ve found that it’s often misidentified when not in flower and confused with other closely related species. Even among foragers who can confidentiality pick out dandelions, I find it isn’t used to its full advantage. So many foragers recommend it for salads, but I don’t love raw dandelion greens. There are far better greens, like chickweed, if you’re looking to make a salad.

Instead, the greens make good additions to pasta dough, stir fry, and pesto. I also harvest and eat the crowns, a tasty suggestion from expert forager Sam Thayer. Just before they bloom, I harvest some of the buds for dandelion capers. Then, I gather blossoms for baked goods and wine. Lastly, I find that the roots make a decent vegetable or an excellent warm beverage when roasted and dried.

Medicinally, dandelion is a powerhouse herb for digestive health! It’s great for treating constipation, heartburn, and upset stomach. It may also have antiviral and anticancer properties. I also like including it in soaps and salves as it may have some benefits for skin problems, arthritis, and muscle soreness.

One dandelion’s other virtues is that it’s generally easy to find. Dandelion loves to grow in sunny openings and tolerates all types of soil. You can find it in urban areas, gardens, lawns, waste places, roadsides, meadows, orchards, and woodland openings.

There are actually quite a few things that look like dandelions that aren’t so be sure you that when you forage dandelions, you take care to avoid dandelion look-alikes.

Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea)

Humans’ relationship with weeds is one that has waned over time. As we’ve increased our grocery store visits and decreased our foraging, ground ivy was one of the common weeds we left behind. I still find it’s an herb worth knowing. This low-growing perennial is a member of the mint family and is a true multi-purpose plant.

Ground ivy has a pretty strong flavor. I use the leaves and blossoms sparingly in salads and as a potherb. With its intense flavor and herbal or sage-like aroma, it’s probably an easy guess that ground ivy has a rich tradition in herbalism. It’s a rich source of vitamin C and may be used for immune support.

Farmers have also used ground ivy as a substitute for rennet, a substance that comes from a young animal’s stomach lining and allows for the separation of curds and whey in cheesemaking. Brewers have used the herb, too. Ground ivy was a popular bitter herb choice for beer before hops were widely cultivated.

Ground ivy can be an aggressive invasive weed in some parts of North America. It’s common to find it growing in areas with moist soil and full sun to partial shade. I often see it forming dense patches in damp sections of lawns, gardens, woodland openings, roadsides, and pastures.

Evening Primrose (Oenothera sp.)

Despite their name, these American wildflowers are not closely related to true primroses. Their name comes from their superficial resemblance to true primroses and their unique flowering strategy. Unlike many species, their blooms remain closed all day and open in the evening when they’re pollinated by sphinx moths, bats, and certain bees.

In addition to being pleasant to look at, evening primroses are edible in their entirety, including their roots, leaves, seeds, and flowers. Though the common evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) is probably the most widely recognized, all the evening primrose or oenothera species are edible. The root has a slightly peppery flavor and is probably the biggest bang for your buck if you’re looking for food. It’s good roasted or boiled and mashed.

Herbalists also use evening primrose medicinally. Most modern herbalists work with the seeds or evening primrose oil extracted from the seeds. There is some evidence that evening primrose oil may help treat certain menstrual conditions when used internally and some skin conditions like dermatitis when used externally.

Evening primrose tolerates a range of soil types but thrives in loose, sandy or gravelly soil. Generally, you can find evening primrose growing in the edges of cultivated areas and yards, construction sites, dry, rocky plains, gravel pits, woodland openings, fallow fields, and lakeshores. Some evening primrose species also grow in desert areas.

Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule)

It’s easy to love henbit. It’s non-native and does tend to be a bit weedy and invasive, but it grows on you, just as it grows across the land each spring. It’s among the easiest edible weeds to pop up in spring and has rounded leaves with toothed edges that look a bit like they’ve been nibbled by a bird. Delightfully, the pinkish, horn-like flowers that form on spikes can be plucked and blown through like tiny kazoos, inspiring the plant’s other common name, fairy horns. In some areas, it also plays a helpful role in reducing erosion from spring rains.

Henbit’s leaves, stems, and flowers are all edible and have a slightly peppery, almost celery-like flavor. You can eat them raw in salads, though their flavor can be a bit overpowering or cooked as a potherb. Many herbalists also use henbit as tea or tincture to treat fevers, pain, soreness, and body aches. It’s also high in vitamin C, iron, and other essential vitamins and minerals.

Henbit is a common weed in many areas, growing in sunny, disturbed sites. You may find henbit in gardens, lawns, pastures, roadsides, and waste areas.

Horsetail (Equisetum sp.)

Few plants are as unusual as horsetail. Horsetail, or Equisetum, is a “living fossil,” the only living genus of the entire subclass Equisetidae, which dominated Paleozoic forests for over 100 million years. Today, it grows in various habitats with moist, alkaline, or neutral soil. You may find it growing in lawn edges, woodlands, stream edges, marshes, gardens, roadsides, and disturbed areas.

Given its age, it’s no surprise that humans started using horsetail long ago. Horsetail is high in silica, making it a great choice for medicinal applications such as improving bone density and speeding wound healing.

Horsetail has two types of shoots. Brown fertile shoots that come up first. These shoots may not look like much, but they are tender, juicy, mild and great for stir fries. Herbalists generally harvest a bit later when the plants send up sterile green stems that look like mini Christmas trees.

In the past, horsetail was also commonly known as scourweed or scouring rush. This is because its high silica content makes it an ideal substance for scrubbing and polishing or scouring pots, kitchen utensils, and other surfaces. Carpenters occasionally used it to buff out wood.

Mallow, Dwarf (Malva neglecta)

Dwarf mallow or Malva neglecta pops up in neglected, untended pieces of land and lawn, just as its name suggests. It’s also an often neglected source of food and medicine. The leaves, fruits, and seeds are all edible and have a mild flavor that’s great for picking up other flavors in a recipe. I love using the leaves with soy sauce and pungent spices like white pepper and ginger in stir-fries.

Medicinally, modern studies have shown that dwarf mallow has promising antibiotic, antimicrobial, and antifungal properties. Internally, I love using it in teas and tinctures for soothing coughs and respiratory issues. Externally, it’s well-suited to poultices and salves for acne, skin infections, and minor wounds.

In an odd twist, mallow has also been used as a “love potion.” Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and naturalist, reported that sprinkling the seeds on your genitals would produce sexual desire. The Iroquois went about it differently, eating and ritualistically vomiting the plant as a love medicine. I think I’ll stick to its non-love-related uses!

Dwarf mallow is fairly easy to spot and identify. It has rounded, palmately lobed leaves and five-petaled, cup-shaped flowers in shades of white, pink, lavender, or blue. The fruits are small, lobed, and green and look a lot like wheels of cheese, which has given rise to a few of the plant’s common names, such as Buttonweed, Cheese Plant, and Cheeseweed.

Mullein (Verbascum sp.)

If you spend a lot of time in the woods, you may know this plant as nature’s toilet paper! Its friendly, fuzzy, large leaves have helped many hikers, foragers, hunters, and wanderers in need. Don’t pass this plant up as just emergency TP, though! Mullein is edible and has some amazing medicinal benefits.

The leaves, flowers, and roots are edible. Don’t eat the seeds; they’re toxic. I find that the leaves are a bit too fuzzy to really be enjoyable, but the flowers are pleasant, mildly sweet, and great for adding color to dishes. I’ve also found that the roots are enjoyable as a vegetable.

Mullein also has a rich history in traditional medicine. Often, it was used as a lung herb. People would smoke the leaves or drink tea from them to help treat coughs, asthma, and other respiratory conditions. Herbalists in the Middle East also used this herb internally to treat worms. Externally, you can use mullein roots, leaves, or flowers in salves or oils to treat skin conditions like eczema, boils, or sunburn.

Mullein’s distinct fuzzy leaves and towering stalk of yellow flowers make it easy to pick out. Its seeds last in the soil for years and wait for disturbances to begin growing. Look for mullein in yards, pastures, forest clearings, roadsides, meadows, and ditches with well-drained, average to poor soil.

Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

This weed is always alluring for young foragers! Its name hints at its wonderful fragrance. Pineapple weed also has the virtue of being highly accessible to urban foragers. It thrives in the compacted soil in lawns and alongside driveways, sidewalks, and playgrounds.

The entire plant is edible, but I’ve found that the greens are quite bitter and unpalatable after the plant has flowered. If you’re looking for greens, harvest them young! Later, the blossoms have a sweet, floral, pineapple-like flavor that’s great for tea and baked goods.

Pineapple weed is sometimes called wild chamomile because it shares many of chamomile’s medicinal properties. It’s a wonderful sedative herb that can help promote sleep and soothe anxiety. It also soothes nausea and digestive issues.

To find pineapple weed, watch for its dense rosette of finely divided leaves with a feather-like appearance. Later, it sends up a flowering stem with alternate leaves. The blossoms look a bit like someone has plucked the petals from small chamomile flowers. If you live in a rural area with good soil, this one will be more challenging to find. Watch for it around driveways, gates, garages, and barn entrances where the soil is compacted and poor.

Plantain (Plantago sp.)

Known affectionately as nature’s bandaid, plantain is another widely recognized species. Its leaves can speed wound healing and reduce inflammation, making them a great choice for quick poultices to treat small cuts, insect stings, and skin irritations. Most people recognize and use common broadleaf plantain (Plantago major), but other Plantago species, like narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata), share its properties.

These helpful plants are also edible and have medicinal benefits when used internally. Though I mostly use it in salves, other herbalists use plantain in teas and tinctures to treat internal inflammation from conditions like IBS and ulcers. The leaves make a decent potherb, especially when young. In parts of Europe, foragers sometimes use the leaves as wraps for dolma. In a culinary sense, my favorite part of the plant is the seeds. Toasted and ground, they make a slightly nutty-tasting flour substitute or can be cooked as porridge.

Though plantain species may vary significantly, they all grow from a basal rosette of simple leaves covered with soft hairs and featuring fibrous, parallel veins. From the center of the rosette, they send up leafless flower stalks, which form a dense spike of seeds.

Plantain is one of my favorite herbal allies because it’s highly accessible. Plantain pretty much grows wherever humans do. Look for it in lawns, playgrounds, gardens, parks, and roadsides where it often thrives in poor, compacted soils.

Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium purpureum)

Purple dead nettle is a sure sign of spring! This beautiful plant quickly colonizes areas of moist soil in the spring. It may be a weed, but I think it’s beautiful enough to be in a flower garden. Its square stems feature alternate leaves that ascend from green to purple with little bugle-shaped pinkish-purple flowers tucked amongst them.

On top of its beauty, purple dead nettle is edible and medicinal. The leaves, stems, and flowers are all edible, though the stems get tough. I love tossing the leaves and flowers into spring dishes; they add incredible color!

Medicinally, purple dead nettle is a potent plant for the immune system. Its leaves and flowers are rich in antioxidants that will help your body fight off illness. Traditionally, it was also used to help reduce excessive menstrual bleeding and some modern research has supported this use.

If you want to find purple dead nettle, you’ll need to watch for it in spring. It comes up early, thriving in cool, moist conditions. Purple dead nettle prefers areas with full sun to light shade and often grows in meadows, gardens, lawns, pastures, and roadsides that offer adequate moisture.

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

Purslane is another one of those funny weeds that many people find a nuisance in the garden while others plant it or purchase it at the farmer’s market, especially in other countries. Personally, I’m glad that this small annual succulent is a widespread weed.

I harvest purslane each year for its incredible flavor, which is sometimes likened to sour or lemony spinach. The stems, leaves, flowers, and seeds are all edible and tasty raw or cooked. Purslane is also nutrient-dense, with high levels of Omega-3s, calcium, iron, and vitamins A and C. It’s good for people and livestock like chickens.

Purslane is also used as a medicinal herb, and part of its benefits may stem from its high levels of vitamins and minerals. Modern research has also found that it’s antibacterial and anti-inflammatory and may help with various conditions, including inflammatory mouth conditions, high cholesterol, atherosclerosis, and nervous system disorders.

Purslane is generally easy to find and identify. It likes open disturbed areas like gardens, yards, roadsides, and waste places and will tolerate a wide range of soil conditions. Purslane is fast-growing and forms creeping mats of vegetation. Its smooth succulent leaves and stems set it apart from most other common North American weeds.

Proso Millet (Panicum miliaceum)

Archeologists think that humans in what’s now northern China domesticated proso millet more than 10,000 years ago! In many places, this is still an important grain crop for humans and livestock, but in places like North America, some of it has also escaped cultivation to become weedy and wild.

Proso millet looks like tall grass until it puts on its long drooping seed head that forms at the top of the stem. While domesticated varieties tend to have yellow or light brown seeds, wild varieties usually have brown or black seeds. Look for proso millet in areas with full sun and disturbed soil. It frequently grows gardens, croplands, waste sites, lawns, and roadsides.

You can use your proso millet harvest much like you would other grains. Grind it into a flour substitute, cook it as porridge, or ferment it into beer. In the United States, some companies still offer gluten-free beer alternatives brewed with proso millet.

Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

Many wildflower enthusiasts will recognize the name Queen Anne’s lace, but many foragers know this plant by its other common name, wild carrot. It is the same species as the domesticated carrot and shares its edible roots, leaves, flowers, and seeds. However, I find it’s much more intensely flavored than the domesticated version.

Modern herbalists no longer focus on Queen Anne’s lace, but it was an important part of traditional medicine in the past. It has been used to treat various conditions, including cardiovascular issues, urinary problems, and digestive problems. The seeds, particularly, also played a role as an abortifacient. For this reason, I recommend that pregnant or breastfeeding women avoid the seeds.

Queen Anne’s lace decorates roadsides, meadows, woodland edges, and waste areas with poor, dry soils. Its delicate white flowers are easy to spot in bloom, but it can be trickier to find this biennial in its first season when it remains a short basal rosette of leaves. The leaves look like carrot leaves you’d see in your garden.

Always be 100% certain of your Queen Anne’s lace identification. Inexperienced foragers have confused this useful plant with its deadly toxic look-alikes, poison hemlock, and water hemlock.

Ryegrass (Elymus canadensis)

This native prairie grass was once an important food source for the Paiute living in parts of the American West. They would harvest the spiked seed heads of oat-like grains and process, parch, and grind them. They used this ryegrass meal to make porridge, drinks, and cakes.

Ryegrass is a short-lived perennial grass species that grows wild in a large portion of the United States. Today, it’s sometimes planted to help restore native prairie and reduce erosion. Like other grasses, it can be difficult to distinguish from other species until it forms its seed heads. The seeds each feature a bristly awn. Keep in mind that if you want to use ryegrass, you’ll need to process it to remove the awn and hull.

Look for ryegrass growing in yards, meadows, open woodlands, fencerows, grasslands, depressions, ditches, and verges. It thrives in sunny areas with moist soil and tolerates various soil types.

Sedge (Cyperaceae sp.)

Foragers often overlook sedges as just another grass species, but many are edible, and some are incredibly tasty. Worldwide, there are over 5,000 sedge species, making this a great group of plants with which to become familiar.

Many sedge species like chufa (Cyperus esculentus), which we discussed above, have starchy edible roots. Some, like chufa are decent-sized and tasty, while others are more suited to survival situations. A few sedge species like the well-known papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) offer an edible pith within their tall stems.

One of the challenges of sedges is that they can be difficult for the untrained eye to distinguish from grass species. Thankfully, sedges have a couple of characteristics that will help you pick them out. First, almost all sedge species have a triangular cross-section, though there are a couple of exceptions to this rule. Second, sedges have spirally arranged leaves, while grasses have alternate leaves.

Sedges also have slightly different habitats than most grass species. Sedge species prefer areas with moist or damp soil. You’re likely to find them growing on riverbanks and in low-lying damp areas in lawns, meadows, croplands, and pastures.

Self Heal (Prunella vulgaris)

Self Heal is one of my oldest herbal allies. Its common names including self heal, carpenter’s herb, woundwort, and heal-all, all hinted at its medicinal value and excited me as a beginning herbalist and forager. Today, I continue to value this plant for its medicinal value, culinary use, and its beauty.

Self heal graces open areas like grasslands, lawns, gardens, waste areas, and forest edges across the United States with its charming purple flowers. Medicinally, it’s a wonderful herb for tinctures and teas to provide immune support and for salves and poultices to treat minor wounds. The bees enjoy its flowers too, and honey made from self heal also has medicinal properties.

In the kitchen, you can also use self heal leaves, stems, and flowers raw or cooked. It can have a bitter flavor, especially raw so I generally use it sparingly in dishes like salads and smoothies. As a potherb, it goes great in omelets, soups, stews, and casseroles.

Self heal is a low-growing, perennial member of the mint family that reaches up to 12 inches tall. Its opposite ovate to lance-shaped leaves help distinguish it from lookalikes like ground ivy. The flowers are tubular with two distinct lips and may be purplish, bluish, or pinkish.

Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella)

If you have grown sorrel in your garden or eaten it in a salad, you are probably familiar with this weed’s tangy flavor. It’s often a hit with young foragers, and its tart, lemony taste has led to common names like sour weed.

Sheep sorrel features distinct narrow, arrowhead-shaped leaves and red-tinted, deeply ridged stems, which make it easy to identify, even for beginners. The flowers form on tall, leafless stems. The female flowers are maroon and generally easier to spot.

It’s a pretty easy weed to find, too. Sheep sorrel grows in open, sunny, disturbed areas with well-drained gravelly or sandy soil. Watch for this tasty plant in lawns, meadows, roadsides, and railroad right of ways.

You can also use sheep sorrel medicinally. Traditionally, herbalists have used this vitamin C-rich herb to support the body and treat conditions like scurvy, digestive issues, UTIs, diarrhea, and inflammation.

Speedwell (Veronica sp.)

Gardeners may be familiar with plants in this family. Some cultivated varieties are often referred to as Veronica, while others are tiny-blue-flowered weeds that creep into moist, rich open areas like gardens, pastures, and lawns.

Thankfully, speedwell is easy to put to good use as it is edible in its entirety. You can experiment with using speedwell in soup and salads, but I’ve found it to have a sharp, astringent flavor. For me, it’s more valuable as a medicinal herb for teas and tinctures.

Herbalists have used speedwell since antiquity. While its exact uses have varied over the years with culture and time, modern scientists have recognized its potent anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties. Herbalists also use it externally for skin irritations, burns, and wounds.

Speedwell includes about 500 species of plants, and their exact characteristics may vary widely across these species. If you’re interested in this herb, it’s worth learning more about the species that grow in your area. They may be low-growing to up to 4 feet tall with ovate, mostly oppositely arranged leaves. Most wild species have four-petaled light blue or blue-purple flowers.

St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Few plants have earned medicinal reputations like St. John’s Wort. Many herbalists and natural health practitioners tout St. John’s wort as among the best herbs for anxiety, depression, and pain relief.

To further add to St. John’s wort allure and mystique, it is among the few herbs that cannot be purchased. To harness the power of this weed, you need to pick it fresh. Dried St. John’s wort from online shops has no medicinal benefit.

Thankfully, you can grow your own St. John’s wort or forage for it. It’s fairly easy to identify. It often reaches 2.5 feet tall and features ovate or oblong 1 to 2 inches, oppositely arranged leaves. The leaves are a key identifier; hold one up to the sun, and it will look like someone has poked holes in it with a need, hence the Latin name perforatum. Its flowers form at the top of the plant, and each features five yellow petals with black dots near the edges. Give St. John’s wort flower buds, flowers, or seeds a squeeze, and they’ll exude a reddish-purple sap onto your fingers.

St. John’s wort’s cheerful yellow blooms grace open lawn edges, hillsides, grasslands, pastures, rangelands and disturbed areas in summer and fall. You can collect St. John’s Wort for salads, teas, tinctures, or medicinal oils.

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

Despite its stinging hairs, sting nettle has been a true ally to humans for centuries. Its leaves may be the best tasting wild green and it offers edible flowers and seeds. Medicinally, stinging nettle is helpful for creating teas and tinctures to help nurture folks dealing with anemia, allergies, muscle pain, UTIS, breastfeeding issues, and gout. Additionally, its stems make excellent cordage and luxurious fabric.

Don’t let the hairs worry you. Stinging nettles are easy to harvest with a pair of gardening gloves and scissors. The hairs are then easily removed by boiling or drying, making the plant safe to eat.

Stinging nettles are fairly widespread and common. They prefer sunny areas with moist, fertile soil. Look for them on the banks of lakes, streams, and rivers or in ditches, moist meadows, fencerows, woodland edges, low-lying pastures, and waste areas.

Typically, you’ll find stinging nettle growing in large, dense patches. They grow straight and tall, featuring coarsely toothed, ovate to lanceolate leaves with pointed tips and distinctive irritating hairs. The stems can reach up to 8 feet at maturity, and you may notice that the leaves have a crinkled appearance.

Violets (Viola sp.)

These little lawn weeds are one of the most charming spring wildflowers. Like me, you will probably find extra joy in their appearance, when you learn to forage and use them as an edible and medicinal herb.

Violets are mild flavored additions to spring salads and baked goods. The leaves contain mucilage that’s soothing for sore throats, coughs, eczema, and other skin irritations. They’re helpful herbs to add to teas and salves.

Violets need consistently moist soil to thrive. Often, I find them along woodland openings and edges of lawns and trails where they receive some shade that helps keep the soil cool and moist. However, in some areas with moist, rich soil, they will grow in open lawns and pastures.

Generally, violets are easy to recognize. The leaves are smooth and heart-shaped. The flowers have five petals in a “star shape,” with the point of the start pointing down. They’re often bluish or purple, but you can occasionally find yellow or white violets.

Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

Wild mustard isn’t dissimilar from the mustard you purchase or grow for salad mixes. When small, wild mustard leaves also go nicely in salads, but they can become hot and bitter as they grow. The flowers also make a good cooked vegetable and have a cabbage-like flavor. The seeds are a bit hot but you can use them for seasoning.

Wild mustard has also been an important medicinal herb. Historically, people often used the herb to create mustard plaster which would be put on the chest or joints to treat respiratory ailments, soreness, and arthritis and had an anti-inflammatory effect. Inhaling mustard vapor when the plant was added to hot water was also used for sinus issues.

While wild mustard is considered invasive in the United States, it doesn’t typically displace native species. It flourishes in manmade disturbed habitats like lawns, orchards, gardens, croplands, pastures, roadsides, and railway right-of-ways.

Watch for its basal rosette of green compound leaves with prominent veins. Later, the plant puts up a flowering stem with red sections and downward-pointing white hairs at the joints. The yellow, four-petaled flowers form in groups at the top of the stems.

Wild Mint (Mentha sp.)

Mint is both a classic medicinal and culinary herb. In the kitchen, it lends its cooling, fresh flavor to savory summer dishes like grilled eggplant and feta and cucumber salad. It also makes a wonderful herb for meat dishes and flavoring desserts.

It’s also among the few medicinal herbs that still see frequent use. A scan of grocery store tea packages will show mint in blends designed for stomach troubles, anxiety, and sleep. I like to use mint in teas, tinctures, and salves.

Mint includes a number of cultivated and wild species, several which can be found growing in the United States. The whole mint family shares characteristic square stems. They also have oblong to lanceolate leaves in opposite pairs and white, pink, or purple flowers. When you find mint, crush a leaf, their fragrance is one of their key identifiers.

In general, mints tend to thrive in open areas with moist soil. Look for them growing in low-lying grasslands, lake borders, moist prairies, and marshes. Sometimes, you will find truly wild mint species that are native or naturalized. It’s also common to come across escaped mint cultivars growing near old farms and homesteads.

Wild Oats (Avena sp.)

Foragers usually focus on wild greens and fruits, but there are a few wild grains to harvest, including wild oats. After harvesting, threshing, and winnowing, you can use these grains just as you would cultivated oats. They’re great for pancakes, oat milk, or porridge.

I also like to use wild oats medicinally as tea. To do this, we need to catch the oats in their milk stage. When you press your thumbnail into a seed, it should exude a white, milky sap. You may have seen these listed for sale as milky oats! I find that they’re great for soothing stress and anxiety.

Wild oats often grow in fields, croplands, lawns, and gardens. When they’re young, it can be hard to pick them out from other weeds; they look a lot like hairy grass. Looking closely, you may notice that the leaves tend to twist clockwise. As they grow older, their main stem reaches up to four feet tall and develops a drooping head of seeds with spikes that hang like pendants from the stem.

Wild Onions & Garlic (Allium spp.) (Crow Garlic, Meadow Garlic, Onion Grass)

Pungent and flavorful, it’s generally easy to identify most of these species as members of the Allium family, just like onions and garlic. Most of them look a bit like small bunches of lush grass or chives, popping up in lawns, gardens, and pastures.

Like cultivated onions and garlic, these lawn weeds are edible and flavorful. The tiny bulbs they produce can be troublesome to dig but you can always cut the tops and use them like chives for flavoring salads, dressings, and dips. When harvesting, only pick plants that have a distinct garlic or onion smell, there are a few other look-alikes but they lack the same fragrance.

Medicinally, wild onions and garlic have largely fallen out of use. Herbalists of the past used them to treat a wide range of conditions and as a general spring tonic. They often put on good growth in late winter or early spring, making them an important early source of greens.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria sp.)

Wild strawberries are common, cute, tasty, and easy to identify. They’re the perfect treat for kids to forage and, in my opinion, worth it for adults, too. Unlike the grocery store strawberries, these little guys are rich in flavor and vitamins. They even have some medicinal properties!

Wild strawberries aren’t picky about their habitat; they tolerate sandy soil and partial shade. You’ll often find them fruiting in lawns, fields, and even areas that won’t support grass. If you have seen cultivated strawberries, the wild ones are easy to pick out. They look like miniature versions with trifoliate leaves, white petal flowers, and red fruit.

I love harvesting the fruit for jam, baked goods, toppings for ice cream or yogurt, or drying them for snacks and granola. The leaves and flowers are great for immune support tea and are pleasant flavored and high in vitamin C.

Wood Sorrel (Oxalis sp.)

It’s hard not to love wood sorrel. Its tangy flavor and beautiful clover-like appearance have attracted many foragers and herbalists. To me, it tastes like a mix of cucumber and lemon and is one of the easiest greens to enjoy as a trailside snack or in fresh salads and smoothies.

Medicinally, wood sorrel is often used as a tonic and is rich in vitamins and antioxidants. Traditionally, herbalists have used it for scurvy, digestive issues, mouth irritations, and nausea.

There are many species of wood sorrel, but they all share a few basic characteristics. Wood sorrels are generally dainty, herbaceous weeds with palmately compound leaves made up of three to four heart-shaped leaflets. I usually find wood sorrel with yellow flowers, but other species may have white, violet, red, or pink blooms.

Wood sorrel species all tend to thrive in moist soil but will tolerate shade to full sun. I find them in lawns, gardens, woodland openings, and waste areas.

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

This celebrated herb has earned a special place in wound care lore and legend. It’s best known for its ability to halt bleeding. Its Latin name, Achillea, comes from the Achilles of Greek mythology, who used the herb to save the lives of wounded soldiers on the battlefield. Surprisingly, it’s also great for internal use, dealing with issues like high blood pressure, varicose veins, and blood clots.

While I often use it medicinally, yarrow shouldn’t be overlooked as an edible herb. The leaves and flowers can be added to salads or baked goods. Some folks also enjoy drying them and grinding them as a spice.

Yarrow is fairly distinct and easy to identify. It has unique, feathery leaves that grow spirally around the stem. From a distance, the flowers often look a bit like Queen Anne’s lace; however, the leaves and smell can help you tell them apart. While Queen Anne’s lace smells like carrots, yarrow smells like chrysanthemum or cabbage.

Yarrow loves open, disturbed areas and is common in lawns and fields. If you learn to recognize its leaves while the plant is still small, you can mow around it to enjoy its growth and blooms as the season progresses.

Edible Wild Plants

That’s my list of common wild edible lawn weeds. What have I missed? What do you forage in the lawn right beneath your feet? Leave me a note in the comments.

Beyond lawn weeds, there’s so much more to discover!

- 100+ Edible Wild Plants – A Forager’s Bucket List

- 50+ Edible Wild Fruits and Nuts

- 20+ Edible Wild Roots and Tubers

- 40+ Wild Plants You Can Make Into Flour

Or, if you’re looking for seasonal guides, here’s what to forage season by season: