Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

Partridgeberry (Mitchella repens) is a evergreen creeping ground cover that’s common in woodlands throughout the United States and Canada. The distinctive berries ripen in late fall, but can be harvested year round as they hang on the plants without spoiling until the following summer.

Partridgeberry was one of the first plants I foraged in the Northeast, though at the time I didn’t know it’s proper name.

I had a college work study job as a field assistant to post doc researcher, and the field work was identifying wild plants, surveying their abundance.

I was a 17 year old freshman, and though I knew many wild weeds, I’d rarely spent time in dense woodlands. No worries, she said, I’d be trained to ID all the plants I needed to know.

The first one she showed me was partridgeberry, and she harvested one and had me taste it. “Tastes like absolutely nothing,” she said, “and that’s how you know they’re Teaberry (Gaultheria procumbens).”

I didn’t think they tasted like nothing, they had a subtle sweetness and mild berry flavor that I quite liked. Either way, I took her word for it, she was the expert after all, and I went around marking them as “teaberry” on my survey.

Years later combing through foraging guide I learned that confusing Partridgeberry (Mitchella repens) for Teaberry (Gaultheria procumbens) is an incredibly common mistake.

The plants are both low growing evergreen ground covers found on the forest floor, and they both produce small edible berries.

If you look closely though, they’re quite different, and the taste is dramatically different. While partridgeberries are sweet and mild, teaberries have an intense wintergreen taste that’s quite startling in a berry if you’re not expecting it.

Either way, tasting a wild berry should be the LAST thing you, only after you’ve positively identified it with other methods. That said, partridgeberries are pretty safe, and all their lookalikes happen to be edible too.

What are Partridgeberries?

Partridgeberries are the fruits of a low growing evergreen ground cover that’s common all across North America. They’re distributed throughout the US, up into Canada and as far south as Guatemala.

Settlers called them “squaw berry” or “squaw vine” since they often observed native women harvesting them.

I recently came across an old black and white video from the early 1900’s that attempts to document the process of making acorn flour, and it follows a native American woman as she processes them start to finish. It’s a silent film, but slides interject periodically with text explaining the process.

Near the end, as she’s finished cooking acorn pancakes by the fire, a slide comes up that says, “And so, at last, her work is finished. The completed project, with a touch of spicy squaw berry, is a delicacy only an Indian can appreciate.”

The incredibly condescending video also likely makes that same mistake misidentifying partridgeberry/squawberry for teaberry, since true squaw berries are not at all spicy (while teaberries are).

Given that “it’s a taste only an Indian can appreciate,” I imagine the film makers they didn’t even try them.

They’re no longer called squaw berry, since they were given that name because they were “something only a native could eat,” and it was meant as an insult.

None the less, they were (and still are) an important part of the traditional indigenous diet, since they’re abundant year round and store well.

These days, they go by the names “running fox” as a translation of an indigenous name, and they’re known as “Noon kie oo nah yeah” in the Mohawk language.

They also go by the name “two-eyed berry,” because of their distinctive appearance, and remembering that name will be incredibly helpful in identifying partridge berry.

Identifying Partridgeberry

Though they’re often confused for other low growing red berries, partridgeberries are actually pretty easy to identify.

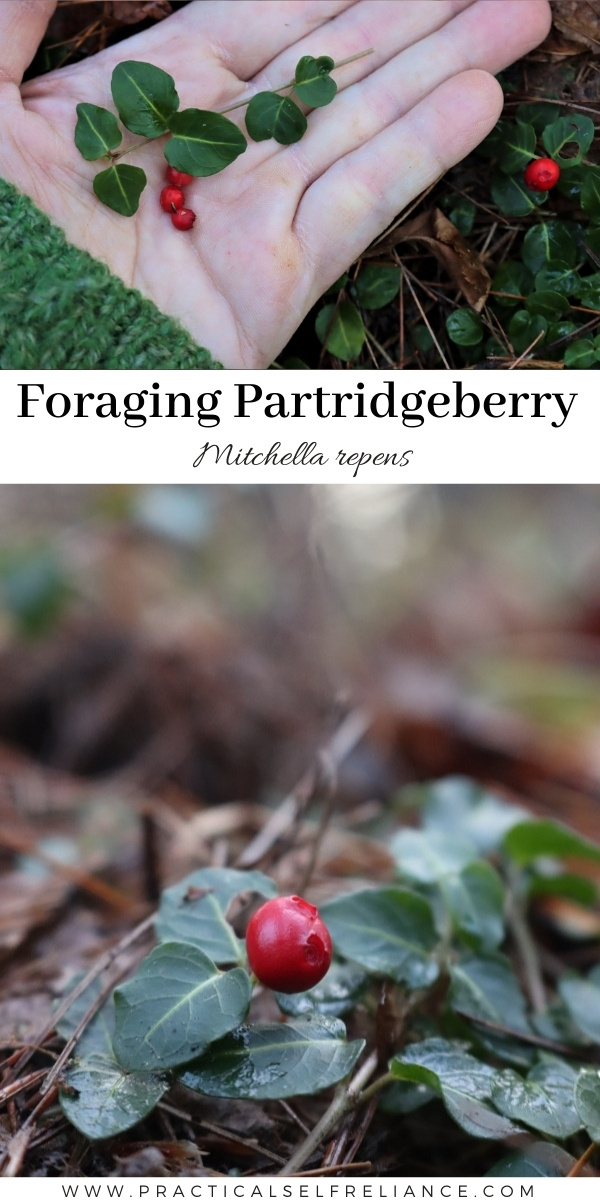

When their in fruit, the berries have a distinctive “two eyed” appearance. That’s because each “berry” is actually two berries that have fused during development.

In the early spring, each one is two tiny white flowers that are pollinated individually. They grow close together, and the berries form into one “two eyed berry” over the growing season.

No other low growing red berry has this characteristic, so that’s an easy way to identify partridgeberry (at least when fruit are present).

Berries are present year round, either as ripe red berries or unripe green berries. Often they’ll overlap, as last year’s red berries will hang on the plant all the way into the summer season.

Using the berries as an identification characteristic is usually dependable, in most places at least. (Unless someone else is harvesting partridgeberries in that spot!)

Besides the berries, the foliage is also distinctive.

It’s a creeping, non-climbing vine that’s usually no taller than 2-3 inches off the ground.

The leaves are evergreen, maintaining their color all winter long under the snow. They’re dark green and shiny, with an oval shape and they’re paired oppositely on the stems.

As the plant creeps along the forest floor, it puts down new roots at leaf nodes and creates a spreading mat of ground cover.

Individual stems can be over a foot long reaching out from the last root cluster, but they’ll eventually root again and continue the spreading pattern.

I usually find partridgeberry in dry, acidic forest soil under pine trees. They’re often near other edible wild berries such as wild blueberries, serviceberries, chokecherry and rowanberry.

Partridgeberry Look-Alikes

They’re commonly confused for other low growing red berries, but all of the common look-alikes happen to be edible as well. (At least, all the look alikes that I know…so always be diligent on your ID.)

Teaberry

The most commonly confused species is Teaberry or Wintergreen Berry (Gaultheria procumbens).

The berries are the same size, and the plants are both low growing. Teaberry is less spreading, usually present as small single plants but in a dense mat that looks like a spreading groundcover.

The leaves are larger, and much tougher than the tender partridgeberry leaves. They also emit a strong wintergreen scent when crushed between your fingers.

Both the leaves and the berries have that same scent.

Lastly, the berries have “single eyes” rather than the “two eyed berry” look of partridgeberries.

Lingonberry

Another low growing red berry, lingonberries (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) tend to prefer a bit more sunlight than teaberries. (Partial shade instead of full shade.)

They grow more upright, usually 8-18 inches tall, similar to wild low bush blueberries. The leaves are much smaller, and the berries are usually in clusters.

They’re delicious, and some of my favorite berries. We actually grow lingonberries, and they’re a much better find than partridgeberries in my book.

Other Look-alikes

The other look alikes I know include wild cranberry (Vaccinium sp.) and bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), both of which are low growing spreading plants with red berries.

The berries are much larger than partridgeberries, and the plants of both have thin woody stems (instead of the soft succulent stems of partridgeberry).

Both of those are also tasty, and found year round even under snow in winter and early spring.

The last two I’ll mention are:

- Bunchberries (Cornus canadensis) ~ They grow in dense clusters on distinctive plants. Hard to confuse with partridgeberry, but they are a red berry that’s close to the ground. (Also edible.)

- Rowanberry (Sorbus aucuparia) ~ This is actually a tree that grows clusters of red berries, but they grow in the same environment. The berries sometimes fall, littering the ground. My four year old once confused a sprinkling of rowanberries on the ground for partridgeberry, which is why I mention it.

How to Use Partridgeberries

Partridgeberries are generally pleasant, but they don’t have all that much flavor. A mild sweetness, some very subtle berry notes, and not much else.

They were mostly consumed by indigenous people as a year round source of nutrients, when other vitamin sources were scarce. They’re also popular with survivalists these days.

Traditionally, they were eaten with acorn cakes, and they’re also a common ingredient in traditional pemmican (dried first).

Wild Fruit Identification Guides

Looking for more foraging guides? I have literally dozens of identification guides for wild berries and fruits…

- Foraging Nannyberry

- Foraging Highbush Cranberry

- Foraging Chokecherry

- Foraging Autumn Olive

- Foraging Serviceberry

HI – I have a Partridge Berry Wreath purchased from a nursery in NH which lives in water throughout the Holiday Season. I am hoping to plant it in the spring. Aside from leaving it in the water until after the frost (I live in CT), do you have any recommendations on how to best keep it thriving? Thank you!

If you keep them in water, they may form roots. If they form roots, you could put them in a pot with some growing medium until it is time to plant them out in the spring.