Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

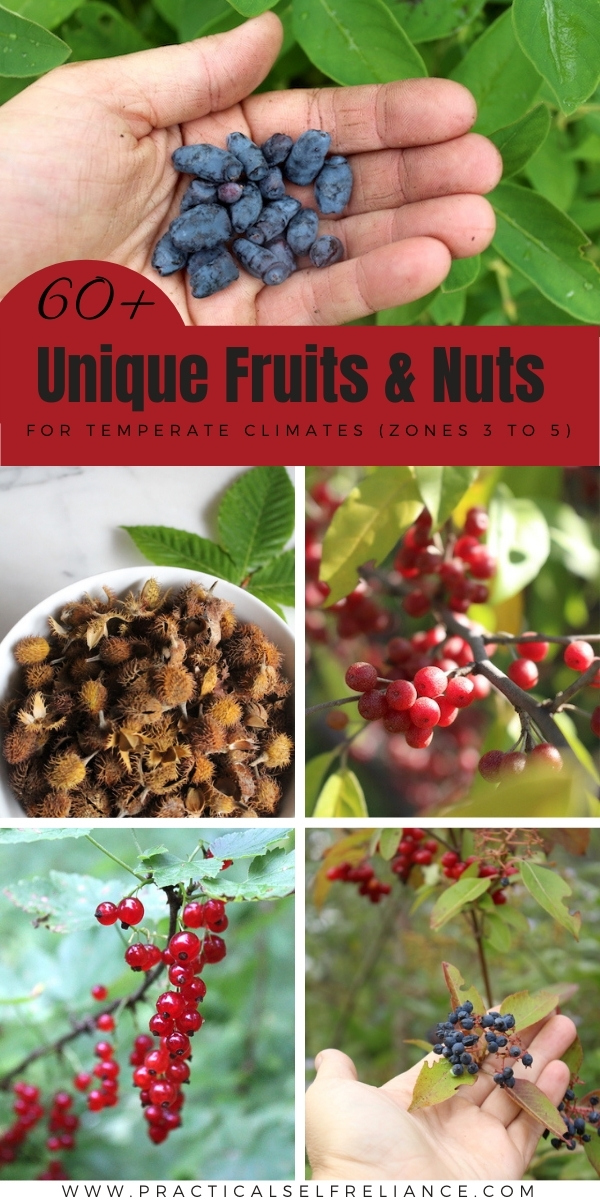

Cold climate gardening can seem limiting, and you just can’t grow many common supermarket fruits. That just means you have to get creative because there are literally dozens of delicious cold hard fruits you’ve probably never tried.

One of the things I really love about permaculture is how the design manuals really think outside the box when it comes to perennial plant varieties.

Alongside apples, pears, and raspberries, you’ll find mention of Cornelian cherries, lingonberries, beach plums, and spicebush —all manner of food forest crops to keep things interesting in the kitchen year-round.

Our permaculture homestead is in a cold zone 4, with temps that occasionally dip as low as -27 F in the winter. While we won’t be harvesting mangoes anytime soon, there are still plenty of options for temperature climate permaculture food forest plantings.

The plants listed below are well suited to grow in zone 3, 4, and 5, providing good yields with minimal effort for a well-planned diverse permaculture homestead.

Aronia Berries (Aronia melanocarpa)

Currently gaining popularity as a new age super food, Aronia berries are actually a wild edible native to much of the US. They come in two main varieties, black Aronia and red (though there’s also a “purple” Aronia, thought to be a hybrid of the two).

They’re easy to grow and resistant to disease, preferring wet soils and tolerating partial shade. Once established, bushes are highly productive and can grow 6 to 8 feet tall.

Hardy in zones 3 to 9.

Apples & Crabapples (Malus sp.)

The vast majority of apple varieties are hardy to zone 4, if not zone 3, and there are hundreds of varieties to choose from.

Don’t just go with the grocery store types you know, branch out and try some really unique varieties by reading through a few well-stocked nursery catalogs. Make sure you plant a mix of summer apples, along with late fruiting good keepers for a solid supply of year-round fruit.

Don’t forget to add in a few crabapples, both for pollination and amazing fruit. Dolgo crab, in particular, is a good choice, as it’s a profuse bloomer with delicious fruit.

Hardy zone 3 to 9, depending on the variety.

Apricot (Prunus armeniaca)

Many apricot trees are hardy to zone 3, but they’re still not common here in Central Vermont. I asked a nurseryman why, and he told me they don’t do well here because of our wet summers. Apricots are susceptible to fungal diseases, and they do better with less humidity and heavy rains. Nonetheless, we’re trying a few out.

The past few years have been hit or miss for rains, and we had one summer with an epic drought and no rain for more than 6 weeks straight. You never know what the weather will throw at you here in New England, and we might just get lucky.

Growing up in California’s high desert, we were often buried in apricots (literally), and we’d make ourselves sick gorging on them. If you have dry summers, they’re a good option, even in cold climates.

Some varieties hardy zone 3 to 9.

Apricot, Manchurian Bush (Prunus mandshurica)

Native to colder regions in Asia, the Manchurian bush apricot is very hardy. The trees naturally stay small, growing about 12 feet high and 12-18 feet across at the widest point.

Though the trees are hardy to zone 3, late frosts can damage the buds and prevent fruiting in the coldest regions. Plant in a micro-climate that melts out late or protects the trees during late frosts.

We planted three near our pond, which moderates temperatures and helps create a more stable micro-climate. Everything I’ve read says they’ll bear fruit in 2-3 years. I’ll let you know how it goes!

Hardy zone 3 to 9.

Autumn Olives (Elaeagnus umbellata)

Another wild edible, autumn olives, are actually considered invasive in some parts of the country. They’re profuse, easy to grow, and birds easily spread the small soft fruit. I’ve seen two varieties, red and gold.

I’m particularly excited about these, but it’s hard to find a source of plants. From what I’ve read, autumn olives grow readily from hardwood cuttings, so if you’d like to mail me a bundle of sticks in late winter or early spring, I’d really appreciate it.

I recently found some from a new wholesale nursery we’re trying out, and they have seedlings available for $4 each or $20+ for named varieties.

Hardy in zones 3-9.

Beach Plum (Prunus maritima)

Once common in coastal regions from the mid-Atlantic states to Canada, Beach Plums have been wiped out by coastal development and population explosions. It is rare in many states.

In spring, Beach Plum trees are covered in white-petaled flowers that turn pink once pollinated. By late summer and early fall, blue-purple plums cover the plant. Wildlife loves these plums, but at one time, so did humans living near these trees.

While tart, Beach Plums are rich in antioxidants and can be turned into delicious jams. Some use these fruits in cordials and wines.

Hardy in zones 3-8.

Beech Trees (Fagus grandifolia)

Though not often thought of as a food source these days, beechnuts were a historically significant source of calories. The nuts are very high in protein and part of Native Americans and early settlers’ diet.

They’re abundant in our woods already and quite productive, though it’s hard to beat the squirrels to them.

Beech trees grow in zones 3 to 8.

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

Often overlooked because the nuts have a slightly more bitter taste than English walnuts, black walnuts can be delicious if appropriately handled. It’s important to get them out of the green outer husk quickly because that husk contributes to the bitter flavor.

The green husk is made into a black walnut tincture (and powder) for use against intestinal parasites and an iodine supplement.

Black walnut trees are also one of the dozens of species that can be tapped for syrup, and they make a unique dark-colored sweet syrup.

Black Walnuts are hardy from zones 4 to 9; some say even to zone 3.

Blackberries (Rubus fruticosus)

Blackberries aren’t as popular as blueberries or raspberries, but they’re an easy berry bush to add to your backyard. I grew up with fresh blackberries from my grandmother’s backyard. She would give me a bowl of blackberries with milk and a sprinkle of sugar – such a good snack.

Once planted, blackberries are easy to grow and do exceedingly well in these USDA zones; they’re native to the area. You don’t need to plant more than one bush because they’re self-fertile, but a few bushes will give you a large yield.

Hardy to zones 4-9.

Blueberries (Cyanococcus)

Everyone has heard of blueberries, and they’re some of the easiest berry bushes to grow. Blueberries take time to grow; it can take up to 10 years for a blueberry bush to reach a mature size, but that means they have a long lifespan.

After planting, expect it to take 2-3 years before you receive any sizable harvest, but they’re worth the wait. While waiting, blueberry bushes are attractive, with leaves turning several shades in the fall.

After establishing, blueberry bushes need simple care, including watering, fertilization, and yearly pruning. Aside from that, you don’t need to worry too much; they handle themselves well.

Their hardiness depends on the variety selected. You can find varieties hardy from zone 3-9.

Buffalo Berries (Shepherdia argentea)

Sometimes called rabbit berries, Buffalo berries are a hardy shrub that reaches between six and 20 feet tall. They’re commonly found along streams throughout the Great Plains in North America.

Fruit appears on the shrubs between August and September in abundance. Buffalo berries are scarlet-red or golden-yellow and have a tart flavor that tastes great when used in relishes or jelly. Besides fruit production, adding buffalo berries to your property gives you a winter hardy and drought tolerant plant that can also fix your soil’s nitrogen issues.

Buffalo berries prefer to grow in zones 3-9, but with adequate protection, they might grow in zone 2 as well.

Butternut Trees (Juglans cinerea)

When I first heard of butternuts, I immediately thought of the butternut squashes I grow in my garden, but these are a type of tree that belongs to the walnut family. Butternut trees are native to the eastern United States and Canada, growing wild in some regions.

Sometimes referred to as white walnuts, butternut trees produce their harvest in late October, developing buttery-flavor nuts. These nuts are popular for baking, fresh eating, and confections due to their unique butter flavor.

Growing butternut trees require well-draining soil and full sunlight, but they adapt well to most conditions. They reach up to 60 feet wide, so space everything else around your trees appropriately.

Hardy in zones 3-7.

Canadian Buffalo Berry (Shepherdia canadensis)

Cousin to the above-listed buffalo berries, Canadian buffalo berries grow in colder climates. These shrubs are typically found in Newfoundland, Alaska, Oregon, and parts of the Rocky Mountains.

These fruits are edible, but some say that the flavor isn’t as desirable as the original buffalo berries. The yellow flowers that cover the shrub eventually produce red berries.

This variety produces dry sites and handles the occasional drought, but they don’t like excessive heat. Production dramatically declines when the temperatures rise too high.

Canadian buffalo berries grow in zones 2-6.

Carolina Allspice (Calycanthus floridus)

These are rarely a common plant you’ll find in your landscape, but Carolina Allspice is a fragrant plant with maroon to brown flowers. The foliage is also fragrant when crushed. These bushes grow well in most soils and climates.

After the flowers, Carolina Allspice shrubs grow fruit that looks like a brown seed pod.

You can let these dry out or use the oven at a low temperature if you don’t want to wait. Once dried, smash and dry them and use them just like cinnamon.

Hardy from zone 4-10.

Carpathian English Walnut (Juglans regia var. carpathian)

Carpathian walnuts belong to the English walnut family, but these trees handle cold temperatures and weather better. They grow further north than other cultivars and produce a steadier harvest in areas with variable winter.

When growing Carpathian walnut trees, give them plenty of space to grow. They grow up to 60 feet tall and 60 feet wide. Expect fast growth; the trees can grow more than two feet per year, especially in ideal conditions, growing best in full sunlight with at least six hours of sunlight.

The nuts are thin-shelled and easy to open, maturing 1-4 weeks before the hull opens. Expect yields of nuts starting in the middle of fall. The nuts are oval and measure up to two inches in diameter. It takes between 4-8 years for the tree to produce any nuts.

Carpathian English walnuts grow in zones 4-7.

Cherry Trees (Prunus avium)

Homegrown cherry trees give you delicious fruit without too much work. Cherries are broken down into two categories: sweet cherries and sour cherries.

Sweet cherries are what you see in the supermarket for fresh eating. It takes between 4-7 years to bear fruit.

Sour cherries are used for cooking, in particular, pies and preserves. Some people call these tart cherries because their flavor isn’t as sweet. These trees take 3-5 years to bear fruit, depending on the variety.

Sweet cherries are hardy in zones 5-7, and sour cherries are hardy in zones 4-6.

Cherry Plums (Prunus cerasifera)

Cherry plums are a particular group of Asian plum trees, and some are a hybrid between plums and cherries. Prunus cerasifera is a native tree typically grown as a small, ornamental tree that produces fruit if there is another pollinator nearby.

On the other hand, cherry plums also can be the new hybrid that is a cross between plums and cherries. These trees produce a cherry the size of a plum. More and more nurseries and tree breeders are coming out with different varieties, some that are hardy down to zone 3.

Hardy from 5-9, but some are hardy down to zone 3.

Chinese Chestnut (Castanea mollissima)

Chinese chestnut trees are a deciduous tree that grows nuts you can eat through September and October. While similar, these are different from the American chestnut trees that, unfortunately, have been destroyed.

In some states, Chinese chestnut trees are grown regularly, such as Iowa. You have to add at least two different trees to your property to produce an adequate harvest. The trees need healthy, fertile soil with good drainage. Space the trees around 30 feet apart; they grow wide.

Be prepared to be patient. Trees start to bear nuts after three to four years and will produce 10-15lbs of nuts per tree after ten years. After a decade or longer, trees produce up to 50lbs of nuts.

Chinese chestnuts grow in zones 4-8.

Chocolate Vine (Akebia quinata)

Many gardeners grow chocolate vines only for the beautiful purple flowers, but they also produce fruits that look like little eggplants in the late summer. These fruits are edible, yet not the most delicious thing.

Chocolate vines are a perennial vine that thrives in the proper conditions. Some of the vines grow as long as 20 feet per year. Due to their length, you’ll need to provide a strong support system as it climbs.

Chocolate vines are hardy in zones 4-8, but they’re only evergreen in zones 6 and above.

Cloudberries (Rubus chamaemorus)

Cloudberry, sometimes called bakeberry, is a creeping plant native to the Arctic and subarctic regions in the north temperate zone. Natives throughout Canada and North America collected these berries for their juiciness.

Markets in northern Scandinavia sell cloudberries regularly. They’re commonly used in tarts, preserves, and other desserts. Cloudberries are yellow or amber-colored fruits that are considered a wild plant in North America. It’s hard to find the bushes for sale in the United States, but seeds are for sale.

Hardy in zones 2-6.

Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas)

The Cornelian cherry (a species of dogwood trees) are a multi-stemmed deciduous shrub with green foliage measuring 2-4 inches long. The shrub produces yellow flowers clusters at the end of winter or early spring, and those flowers turn into edible red fruits.

That means this is one of the earliest blooming shrubs in the spring. In Europe, Cornelian Cherries are used for drinks, syrups, preserves, and jams, eaten fresh or dried. Make sure they’re fully ripe for reducing some of their bitterness.

Cornelian cherry shrubs are slow-growing; it takes up to 10 years to reach the maximum height of 15 feet. They need full sunlight to partial shade with well-draining soil in the acidic to slightly alkaline range (5.0 to 8.0).

Hardy in zones 4-8.

Currants (Ribes)

There are three types of currants – red, black, and champagne. Each is better for different uses.

Red currants have a balanced sweetness and acidity, making them ideal for jams, sauces, and baked recipes. Pink and white currants (sometimes called champagne) are the less acidic variety and suitable for fresh eating. Black currants have a high vitamin C content with a robust and unusual flavor that most don’t prefer.

Currants harvest in mid to late summer. They grow areas with full sunlight and a pH range of 5.5 to 7.0. Currant bushes reach 3-6 feet tall, producing large amounts of berries.

Hardy in zones 3-8.

Elderberries (Sambucus)

Elderberries experienced a revival in recent years as their health properties came to light. Now, people use elderberries to create elderberry syrup to be used when someone is sick or feeling under the weather.

Elderberries are a native plant in North America, growing wild in many parts of the country, and you can grow elderberries as well. They’re among the easiest berries to grow because they tolerate a wide range of conditions, from too wet areas to poor soil. Elderberries won’t tolerate drought.

Elderberries are hardy in zones 3-8.

Ginkgo Nuts (Ginkgo biloba)

In recent years, Ginkgo biloba started to make a name for itself, touted as a remedy for memory loss. The trees produce fruits with a distinct odor, so many people don’t realize they’re considered edible. When the fruits drop to the ground and squash, the unpleasant smell is released.

Yes, the fruit itself is edible if you can get over the scent. Most people prefer to eat the nuts inside of the fruit, which are considered a delicacy. Ginkgo nuts look similar to pistachio with a soft, dense texture, but they’re mildly toxic, so eat small amounts at a time. In Japan, Korea, and China, Ginkgo nuts are sold as a seed as the “silver apricot nut.”

Ginkgo biloba is hardy in zones 4-8.

Goji Berries (Lycium barbarum)

Often known as wolfberries, goji berries are a hardy berry plant that grows in most USDA zones and handle drought conditions well. The berry plants produce bright orange/red fruits that have a slightly sour flavor. Goji berries are highly sought after and considered a superfood because they boost your immune system.

Make sure you pick a spot with full sunlight, but they can tolerate partial shade. The plants can be trained to grow up a trellis like a grapevine. You also can grow goji berries in containers.

Goji berries grow well in zones 3-10; some say up to zone 2.

Gooseberries (Ribes uva-crispa)

One of the easiest fruit bushes for beginners is gooseberries; they’re underrated and too often forgotten. They grow well in most soils, self-pollinate, prune easily, and produce large harvests. What’s not to love?

Gooseberries thrive in most gardens, but for ideal harvests, pick a spot with bright sunlight and rich, well-draining soil. Once harvested, try cooking gooseberries in pies or add them to a sweetened cream to make a treat called gooseberry fool.

Hardy in zones 3-8.

Goumi (Elaeagnus multiflora)

Goumi berries come from the goumi plants, a springtime treat in other regions of the world. The berries are bright red with silver speckles, known for being high in vitamin A and essential fatty acids.

Growing goumi plants in your garden is a smart idea because they’re nitrogen fixers. Goumi bushes take nitrogen out of the air and put it back into the ground, improving the fertility in the soil around it. That makes it a fantastic addition to any garden.

Depending on the variety, goumi is hardy in zones 4-9.

Grapes (Vitis spp.)

Gardeners often skip over adding grapes because they seem like they’d be hard to grow, but once established, grapes can grow for decades, making them an excellent addition to your perennial garden.

My great-great-grandmother planted grapevines when she became a mother, and those same grape vines are growing and prolific today. The plant is over 100 years old and, because they’re well-tended, produce a sizable harvest each year.

Most importantly, grapes need a support system, typically an arbor, for the vines to grow upward. Spend time learning how to properly train the vines if you want to grow grapes successfully.

Hardy in zones 2-10; look for one for your region.

Hardy Kiwis (Actinidia arguta)

We can’t grow kiwis in zones 3-5 because they’re tropical fruits, but instead, we can grow hardy kiwis. These fruits have smooth skin, unlike the hairy skin of a tropical kiwi. They’re also smaller and sweeter.

Hardy kiwis taste similar to regular ones. It’s nice not having to peel the skins off to eat them. Most people grow hardy kiwi as a landscaping plant because of their heart-shaped foliage, but why not enjoy the fruit along with the beauty?

Hardy in zones 3-9, depending on the variety grown.

Hardy Pecan (Carya illinoinensis)

Hardy pecan trees are a deciduous tree that is the largest in the hickory family, often reaching upwards of 100 feet tall. This native tree adapts well to cold climates and looks beautiful while doing so. Its large size makes an excellent shade tree for a larger backyard while providing you with plenty of nuts.

Hardy pecans can live for 75-100 years, so it’s a tree you plant when you know you’re staying put. It produces thin-shelled pecans, but it can take between 7-15 years to begin production.

You might have used pine nuts in recipes before; they’re typically used to make pesto or tossed into salads. The trees produce their nuts in the spring, but it takes 5 years after planting to develop.

Hardy in zones 5-9.

Hawthorn (Crategeus sp.)

You can find dozens of different hawthorn varieties, but all hawthorns produce berries. If you have kids, you might want to grow the thornless varieties.

Hawthorn seeds, like apple seeds, contain cyanide, so you don’t want to eat them. Just spit them out instead. Instead, you can use hawthorn berries to make jelly (not jam, you want to filter out the seeds) or a tea out of the berries, leaves, and flowers.

If you want your Hawthorn tree to produce berries, make sure the tree has plenty of sunlight. You can find berry-less Hawthorn trees everywhere because they don’t receive enough sun.

Hardy in zones 5-9.

Hazelnut (Corylus avellana)

These trees are some of the smallest nut-producing trees, only reaching 10-20 feet tall and 15 feet wide. If you have a small backyard, hazelnuts are a good option if you have well-draining soil that’s amended well with nutrients.

American hazelnuts grow in the colder regions, but temperatures below 15℉ kill crops. European hazelnuts prefer warmer temperatures.

Hazelnuts ripen and drop from the tree in the fall. Rake the nuts into a pile to harvest, gathering every few days. Typically, the first nuts are empty, but over time, you’ll receive larger harvests.

Hardy to zones 4-8.

Highbush Cranberries (Viburnum opulus)

Highbush cranberries aren’t actually cranberries despite the name, but they have similarities. Both grow their fruits in “drupes,” and the berries look like cranberries in size, color, and taste. Also, both highbush cranberries and cranberries mature in the fall.

The difference is that highbush cranberries belong to the honeysuckle family and are considered endangered or threatened in many areas.

Like cranberries, you can eat highbush cranberries raw or cooked. They’re rich in vitamin C and have a tart, acidic taste. If you find a recipe that uses cranberries, use highbush cranberries instead; they work in jams, jellies, sauces, and preserves.

Hardy in zones 2-7.

Hobbleberry (Viburnum lantanoides)

Hobbleberries are mainly known for their medicinal uses; the leaves are analgesic. Herbalists use them as a poultice as a migraine remedy. They’re still a berry plant that produces edible berries!

Hobbleberries can be eaten raw or cooked. They’re sweet, tasting similar to dates or raisins. Inside, there is a large seed, and the flesh is thin. The taste improves after a frost.

You’re more likely to find hobbleberries in nature than propagated in someone’s garden. They can be found throughout New England, making them a wild fruit for foragers and hikers.

These are hardy in zones 3-7.

Honeyberry (Lonicera caerulea)

Also known as haskap berries, these are some of the hardiest northern berries. They’re good to zone 2, and they actually don’t grow well above zone 6. There are a few warmer climate varieties that will tolerate zone 8 and not die, but they really do need cold to thrive.

They taste like a cross between a blueberry and a grape, though most varieties are quite tart. We eat them out of hand and enjoy them in the garden as the first fruits of the season, ripening at least 2 weeks before the first strawberries.

(They also make an excellent honeyberry jam without the need for added pectin.)

The blooms are frost-hardy, and they’re a great early nectar source for the bees. Ours are always covered with native bumblebees when in flower.

Hardy in zones 2-6, with some varieties tolerating warmer temperatures up to zone 8.

Honey Locust (Gleditsia triacanthos)

Honey locust trees are deciduous trees growing native in central North America. It produces blooms in the late spring. The tree received its name due to the sticky pulp it makes that feels similar to honey. It’s been used for centuries in medicinal practices.

Nowadays, most honey locust tree fruits are used to feed livestock. Humans rarely use it as food, but historically, it was.

According to the USDA, “the geographic range of honey-locust probably was extended by Indians who dried the legumes, ground the dried pulp, and used it as a sweetener and thickener. Although the pulp is also reported to be irritating to the throat and somewhat toxic, fermenting the pulp can make a potable or energy alcohol. Native Americans sometimes ate cooked seeds. They have also been roasted and used as a coffee substitute.”

Hardy in zones 3-9.

Korean Stone Pine (Pinus koraiensis)

Korean Stone Nut Tree is an attractive tree with plenty of dark-green needles and large, delicious nuts most commonly gathered in Korea and eastern Russia. Korean Stone Pine Nuts have a rich, delicious taste while being full of nutrients.

Expect these stone pine trees to bear 20lbs of nuts or more, starting five years after planting. At full maturity, the trees measure 60-70ft. Since they’re self-fertile, only plant one tree until you want tons of pine nuts.

Hardy in zones 3-7, but some says it’s hardy in zone 2 as well.

Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea)

Sometimes called foxberries or rock cranberries, lingonberries belong to the same family as blueberries and cranberries. The bushes grow throughout the Northern Hemisphere, producing fruits used for jelly and fresh juices in northern European countries like Scandinavia.

Lingonberries grow densely and can be harvested by raking. Bushes produce large amounts of small, deep ruby-colored, tart berries. They’re similar to cranberries in taste and uses. If you grow large quantities, not only can you make jams and condiments, you can also freeze them for use later.

Hardy in zones 3-8, but some say up to zone 2.

Magnolia Vine (Schisandra chinensis)

Magnolia vines are a hardy perennial and ornamental plant that produces beautiful, fragrant flowers and tasty fruits. It’s native to Asia and North America, growing well in cool, temperate climates. They have to go dormant in the fall, so Schisandra vines tolerate low temperatures.

In the mid-summer, the berries start to turn deep red. They have a sweet and slightly acidic flavor that tastes great, whether eating raw or cooking. Sometimes, magnolia vines are called the five flavor fruit because they have everything! The shells as sweet, but the meat is sour. The seeds taste bitter, and the extract is salty – unique, right?

Hardy in zones 4-7.

Mulberry (Morus alba)

Nothing screams summer like little kids running under the mulberry tree, ending up with stained feet. The mulberry tree in our backyard is nearly 30 feet tall and 30 years old, producing berries steadily each year without any help from me.

Growing mulberries is quite simple. Plant the trees in full sunlight and rich soil, but the trees tolerate part shade and different soil types. Once established, mulberry trees require little to no care.

Watch out for volunteer mulberry trees. When birds drop the seeds, mulberry trees pop up everywhere. Mulberry trees aren’t small trees; some varieties can reach up to 50 feet tall. So, don’t plant the tree near a sidewalk, other trees, or your house.

Mulberry trees are hardy to USDA zones 4-8, depending on the variety.

Nanking Cherry (Prunus tomentosa)

If you want cherries without growing large trees, Nanking cherries are an excellent option. Originating in Asia, Nanking cherries came to the United States in the 1880s and gained popularity rapidly.

Nanking cherry shrubs are fast-growing and set fruits within two years. If you don’t prune, they reach 15 feet, but they also spread out, growing like a shrub or hedge.

This bush cherry tree produces small, dark red cherries that are tart and delicious, ripening in July and August. They tend to be softer than other cherry species, but they have a shorter lifespan. You can use them for fresh eating, preserves, wine, juice, and pies.

Hardy in zones 3-6.

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago)

Typically used as a landscape shrub, nannyberry is a bush or small tree that can reach 20 feet tall. It’s a Midwest native plant found in woodlands.

Nannyberry is related to elderberry, and the fruits are edible. The fruits are slightly-flattened berries that measure up to ½ inch long, starting green and turning purplish-red then dark blue-black. The berries are sweet and can be used in many of the same ways you’d use elderberries.

Hardy to zones 2-8.

Northern Wild Raisin (Viburnum nudum)

Northern Wild Raisin is a native plant to the Eastern United States, thriving in wet, shady areas. While edible for humans, the wildlife enjoys munching on these fruits, and they make an excellent choice for a permaculture garden to create shaded areas.

The plants produce berry-like fruits that are ⅓ inch long. Appearing on red stems, the berries change colors as they mature, going from yellow to green then evolving to a dark blue-back. In most areas, they develop by mid to late September.

Hardy from zone 3-8.

Oak Trees (Quercus)

Without a doubt, oak trees are one of the most common tree species in North America, but their numbers are steadily declining. Oaks belong to one of two groups: red oaks and white oaks. Red oaks have pointed lobes with bristles at the tip, and white oaks have rounded lobes.

Come fall, oak trees drop pounds of acorns on the ground. As the weather turns colder, gather the acorns you find on the ground. Don’t take them off of the tree; those aren’t ready.

Acorns are edible, but they need to be processed and leached of tannins before they’re eaten. After that, you can eat the acorns or turn them into acorn flour, a fantastic substitute to use in your kitchen.

Hardiness depends on the variety grown, but many are hardy in zones 3-9.

Partridgeberry (Mitchella repens)

Though they’re incredibly common, partridgeberry is easy to miss in the landscape. They’re low-lying, creeping plants, but it turns out these plants grow an edible berry that you can enjoy.

Partridgeberries are bright red, but sometimes white, and have two lobes because of the flower’s fused ovarian structure. While these berries are edible, they are fleshy and not tasty. The most common way to use partridgeberries is to dry the leaves as an herb. Native Americans made a leaf tea for women in labor.

Hardy in zones 4-9.

Paw Paw Trees (Asimina Triloba)

If you live in a region where you can grow the American Paw Paw, make sure you add one. The fruits have a delicious, creamy fruit, growing on a tree with tropical-looking leaves and gorgeous blooms. You’ll find that the fruits have a custard-like texture, making them perfect for desserts.

Aside from growing yummy fruits and looking beautiful while doing so, Paw Paw trees are hardy down to -10℉, so you can enjoy tropical-like fruits even if you live in colder areas. The trees need to grow in full sunlight in a somewhat sheltered location because high winds can damage them.

Come fall, you’ll have a large harvest to enjoy.

Paw Paw trees are hardy in zones 5-7 as perennials.

Peaches (Prunus persica)

While many varieties of peaches are only hardy to zone 5, there are several zone 4 hardy peaches that have recently come on the market.

You still need to take care to plant them in a warm microclimate that melts out late in the spring to encourage the flowers to break bud late in the spring, thus avoiding damage by late frosts.

A few people are growing them successfully here in central Vermont, so we’re going to give them a try this year.

Some varieties are hardy to zone 4, but most 5 to 9.

Pears (Pyrus)

Chances are you’re familiar with pears; any grocery store carries, at least, one variety or more. You might not know that dozens of different pear cultivars exist, so finding one that works best in your area is a good idea. That increases your yield and decreases pest problems.

Pears are an all-around excellent fruit tree to add to these USDA zones. Unlike peaches, which are less hardy, pears handle the cold temperatures well. Experts say that pears are easier to grow than apples, which I believe. My in-laws have a pear tree in their backyard that they give no care, and it steadily produces each year.

Hardy in zones 3-10; find one that grows best in your zone.

Persimmons (Diospyros virginiana)

Persimmons have grown in North America for centuries, valued by Native Americans and early settlers. These fruits hung on the tree in the winter, providing much-needed food. When left to ripen on the tree, persimmons taste similar to apricots.

Persimmons are easy to grow and not picky about their conditions. They grow best in sunny spots and need plenty of water. They don’t handle drought periods well, and you don’t need to worry about fertilizing often.

Hardy in zones 4-9.

Plums (Prunus spp.)

Like peaches and cherries, plums are a stone fruit that grows well in most backyards. Plums make delicious jams and cakes, as well as tasting delicious for a fresh snack.

You need to pick a plum cultivar that works best for your location. All plum trees can be broken down into three categories, with the hardy European plum trees growing well across most of the United States. American hybrids are the hardiest varieties, surviving as far north as zone 3.

Plums are hardy from zones 3-9, but American hybrids and European plums are better for zones 3-5.

Rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum)

After tasting rhubarb, you wouldn’t believe it’s technically a vegetable, but no one eats them like a veggie. Rhubarb is a perennial plant that produces tall, red-pink stalks with a unique sour taste. It looks like pink-red celery, but the plants can reach large sizes and produce for 15-20 years each spring.

Rhubarb tastes best when baked or added to jams or jellies. I make a delicious strawberry-rhubarb jam in the spring and a sour cream rhubarb pound cake that everyone loves. You can easily add a rhubarb plant or two in an empty garden bed spot.

Hardy in zones 3-8.

Rose Hips (Rosa canina)

I first heard of rose hips from a popular YouTube homesteading channel and became intrigued by their many uses. These homesteaders had dozens of native rose hip plants growing near their home, and they turned them into homemade ketchup, barbeque sauce, jams, and more. I knew I needed to learn more.

It turns out that rose hips are the rose plant’s seed pods rather than a particular plant themselves. The hips are the fruit, looking like a small cherry. The Rugosa variety of roses produces the best hips, and Rugosa Roses bloom from spring until the first frost.

Rose hips are hardy in zones 4-7.

Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides)

It’s often called sea berries, sea buckthorn gained popularity because it’s a new superfood, but it’s been on the list for permaculturists for years. Sea buckthorn is a hardy perennial plant that is a nitrogen fixer, so they grow in soil that might not be the best.

These bushes produce bright orange berries that are quite tart when compared to other fresh berries. Sea berries will make your lips pucker, but kids find them fun to eat. It’s best to press sea berries into a juice or make a sweetened jam.

Hardy in zones 3-8.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.)

Serviceberries are a large shrub or a multi-stemmed, small tree. They can be used in landscapes, backdrops, or borders. These provide year-round, white spring flowers and edible, purple fruits. The ripened fruits can be eaten fresh or used in jams, jellies, and pies.

Serviceberry trees prefer loam soil but tolerate sandy and clay soil. They grow best in well-draining soil with a pH range from 5.5 to 7.0.

Hardy in zones 4-8.

Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovata)

This Midwest native tree received its name because of its bark that has a shaggy appearance. The bark peels away in large, curving plates. It’s most commonly found in the Chicago area and other similar places in North America, reaching mature heights of 60-80 feet.

Shagbark hickory is a member of the walnut family, producing edible nuts that ripen in the fall. If you decide to grow a Shagbark Hickory tree,

Hardy to zones 4-9.

Shellbark Hickory (Carya laciniosa)

Once a common tree throughout the Midwest, few Shellbark Hickory trees remain throughout the United States, meaning that this is a threatened species. That gives you a particular reason to add these towering trees to your yard.

As a member of the walnut family, Shellbark nuts are the largest out of all the trees. With the husk on, the nuts measure up to 2.5 inches in length. The leaves on this tree also are large, stretching up to 22 inches. Shellbarks are slow-growing trees, growing less than 12 inches per year and reaching 60-80 feet at full maturity.

Shellbark Hickory trees are hardy in zones 4-8.

Siberian Pea Shrub (Caragana arborescens)

Native to East Asia and Mongolia, Siberian pea shrub is considered an invasive plant in some areas. Make sure you check your state because they’re prohibited in some due to their invasiveness.

Siberian pea trees gained popularity in the permaculture world recently. By September, the seeds are ready, contained in pods; each pod has 4-6 seeds, just like peas. The seeds have a mild pea flavor, but eating them raw isn’t recommended. You can cook them, and it creates a lentil-like seed for dishes.

Hardy in zones 2-8.

Silverberry (Elaeagnus sp.)

Related to Autumn Olives, silverberries are another vigorous nitrogen-fixing fruiting perennial.

The bushes prefer full sun but are shade tolerant, so they’re sometimes used as a nurse shrub in young nut orchards for nitrogen feeding. Some varieties are quite thorny, and they’re used as living fences.

Some varieties are only hardy in zones 7 to 10, but the “Hardy Silverberry” (Elaeagnus commutata) is grown in zones 2-7.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

Spicebush is a deciduous shrub with glossy leaves and pretty green branches with leaves alternating. As the plant grows, dense clusters of tiny, pale, yellow flowers bloom. The fruit and leaves are aromatic with a rich, earthy scent.

Both the leaves and berries on the Spicebush are edible and can be eaten raw or cooked. You can make tea from all parts of the plant. The berries ripen in the early fall and have a similar taste as allspice, the seasoning you’ll find at the store. You can add some of the berries to your baking or pie recipes.

Hardy in zones 4-9.

Strawberries (Fragaria spp.)

One of the most popular fruits grown at home is strawberries because they’re so easy to grow. Strawberries grow in containers, raised beds, over pergolas, and anywhere you want. The plants produce runners which continue the spread; strawberries can be invasive at times.

Growing strawberries is an excellent introduction to fruit growing for beginners. They can be used in thousands of recipes, so it’s worth adding a few to your garden.

Hardy in zones 2-10, but find one that works best in your area.

Teaberry (Gaultheria Procumbens)

Teaberry plants are native to New England, peaking in mid-October. For years, teaberries were used commercially to make chewing gum, and it’s also been used medicinally for centuries. You can use the berries to make tea and wine as well.

Teaberry is an evergreen species that prefers wet woodland areas for optimal growth. If moss and ferns grow nearby, teaberries will as well. The plants have white flowers that mature into pea-sized, red berries that might have a pink tint. When eaten raw, teaberries have a fragrant scent with a berry flavor hint under the warm minty spice.

Teaberries are hardy in zones 3-8.

Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)

Thimbleberries are native to many areas of the United States, growing near woodland areas. They’re large plants, reaching up to 8 feet tall. In the wild, thimbleberries are easy to identify because they have large leaves that look like a 3-pointed maple leaf.

Thimbleberries look like raspberries yet wider and flatter. The fruits are soft and delicate and spoil fast after damaging. Damaging and bruising often happens at harvest time, so fresh eating is how most are used.

Hardy in zones 2-6.

Yellow Horn Tree (Xanthoceras sorbifolia)

I only recently learned about yellow horn trees, and I have no experience with them. According to Burnt Ridge Nursery, this “unusual hardy tree native to Northern China. Numerous pea-sized nuts are produced in 2″ seed capsules. White flowers to about 1” in spring. Compound leaves are 1 ft. long. Very ornamental small tree. The leaves, flowers, and nuts of the Yellowhorn tree are edible. Zone 4 – 8.”

Try Growing These Unique Fruits & Nuts

If you live in USDA zones 3-5, you aren’t limited; there are many different fruits and nuts you can grow. Take advantage of the abundance of plants that grow in these regions, and create your permaculture garden dream.

Permaculture Topics

Looking for more information on Perennial Agriculture?

- 30+ Perennial Vegetables

- How to Plant an Orchard for a Year Round Supply of Fruit

- Growing Garlic as a Perennial

- 40+ Plants You Can Turn into Flour

- 50+ Wild Berries and Fruits to Forage

Great article. After researching PINUS KORAIENSI, it appears I need more information about which variety. Can you provide specific information I would like to make sure I purchase the nut producing variety you referenced. Thank you.

Hey Ashley! This was a fun post to read. I am just starting my own homestead. We are three years in and I’m focusing on ramping up my perrenials this year. We have Autumn Olives! I have some cuttings rooting as we speak. I foraged them from a nearby park where a friend of mine says she collects the berries every year, they’re so yummy. I’d love to arrange a swap if you’re interested. I am still looking for schinsandra, butternut and goumi this year but have tapped out on funds haha. Let me know if you’d like to do a mailing swap, or depending on where you are we could even do a playdate meetup in a safe and public place. My kids are 7, 6 and 3. We are in the upper valley of NH, so on the VT boarder. I always love meeting others living the dream. Hope you have a fun and productive spring/summer/fall.

-Kristi

Autumn olives are quite delicious but they are also seriously invasive so it’s best not to propagate them but instead to forage for them where they’re already growing. This actually helps to keep them from spreading further.

Hi Ashley,

I am trying to find seeds or a baby shrub or two for cloud berries, and wonder if you have a source. I am located in Berlin, VT, which is a Zone 4b, approximately, although I’ve successfully grown some plants that are Zone 5 here. I really enjoyed this article, lots of great info that is pertinent to Vermont. Thank you, Gale Harris

Hey Gale, I know Berlin well. I too would love to have cloud berry plants, but I haven’t found anywhere that has them. There is a Nursery in Berlin that might be able to help you. Try contacting A Perfect Circle Farm (right in Berlin). They don’t carry them as far as I can tell, but they may be able to help you find them somewhere as they specialize in obscure food plants like this. https://www.perfectcircle.farm/

Have you looked into the Siberian pea shrub?

No I haven’t. Do you have some information on it?

I love your site so much! What an amazing resource, thank you for compiling this list, I. can’t wait to. try growing some of these! One thing I’d love to see you cover someday is the American groundnut. I’ve eaten a few I found foraging and I would love to someday grow them in my garden- such a beautiful flower and the tubers have a really unique taste.

Ground nuts are actually mentioned briefly in this post. https://practicalselfreliance.com/perennial-vegetables/ Do you have a specific question about growing them?

Just checked it out, thank you! Unfortunately I think my soil is too clay heavy, so I’ll just have to stick to foraging them for now.

I can understand that problem. You could always think about adding in some raised beds or growing them in containers.

I’m looking for Nursery Sources for these plants. Please advise

Thank you for this resource! I’m new to rural Vermont and was worried about gardening – your website is so encouraging!

You’re very welcome. So glad you are enjoying the website.

Another great article! More on my wish list. You have a nice picture of hand full of honey berry but I seem to have missed the write up. I have grown them in both zone 5 and zone 3. One of my favorites. Blossoms seem to tolerate frost, first to bloom in the spring so early food source for bees. Taste like cross of blueberry and raspberry. I like the way morning dew collects to make them look jewel studded. Square bottom is unique because 2 flowers for each berry giving rise to another nickname twin berry. Need pollinator, variety of sizes

Oh my goodness, that’s so funny. I put so many in there I forgot the one that got me started writing that article in the first place! Just added them, thanks for catching that!

LOVE this post. Oh my goodness, so much great info here – I will have to absorb over the course of multiple sittings.

I do have a question though: Would any of these plants grow well in containers? I live in an apartment, so I am limited to a balcony garden (zone 4).

Thank you for helping me thing this one through.

Hmmm…many of these are big woodland trees, which wouldn’t do well in containers. Things like lingonberries, blueberries, honeyberries, rhubarb and maybe even raspberries would do well in containers though. Most of the smaller bushy type plants, rather than the trees.

I LOVE your site and daily use it to gain knowledge. I would LOVE to send you some Autumn Olives. We live in Massachusetts and picked 40lbs. last year and only dented what was near our property.

So, please email me if you have not yet found another source.