Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

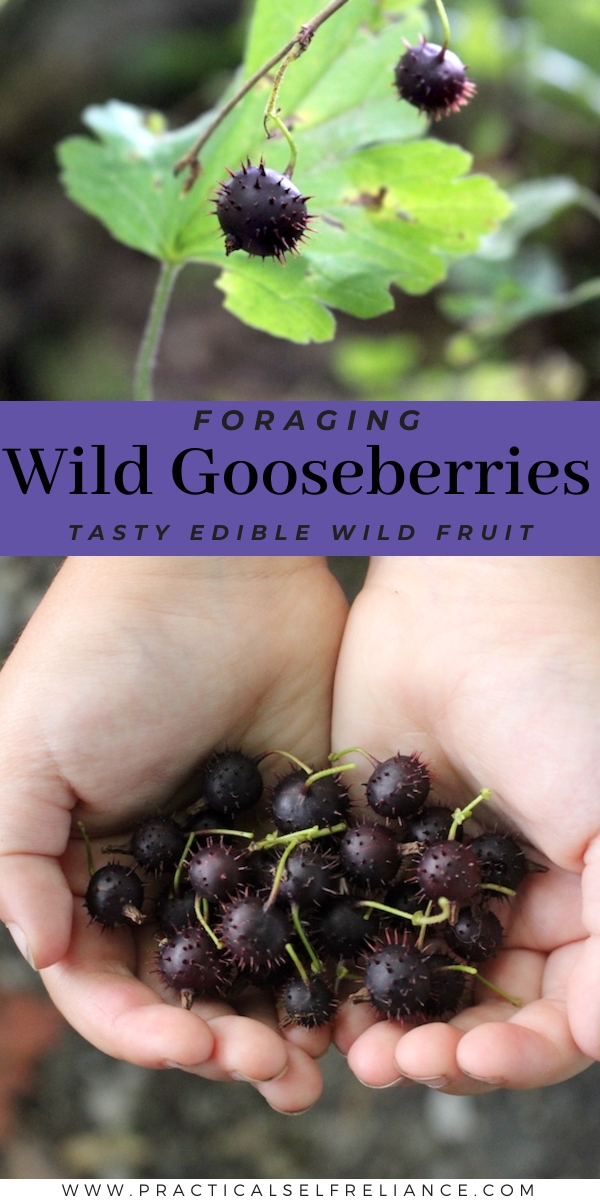

Wild gooseberries (Ribes sp.) can be prolific in shady, wet woodland locations. The distinctive spikey fruits are certainly eye-catching, and they’re well worth the foraging effort.

Spikey fruit isn’t exactly inviting, but gooseberries are tasty, I promise!

We grow gooseberries on our land, and cultivated varieties are a bit more inviting. They don’t tend to have spines on the fruit themselves, just the bushes. They’re prolific producers of sweet-tart fruit and an ideal way to put shady wet spots to good use in a permaculture food system.

Wild gooseberries are just as prolific, and they’re common in moist woodland locations across the country. They’re a common sight along woodland trails and forest edges, as well as in more shady locations. (Though they’ll fruit best in good sun.)

They may look intimidating, but the spines are reasonably soft on the fruit themselves, and you can, in fact, eat them out of hand. (Hand one to a toddler, though, and they’re going to be a bit confused…how am I supposed to eat this spikey thing!?!?)

Watch the bushes, though; they have some serious spikes. Wild gooseberries can be harvested with bare hands if you’re careful, avoiding the spiny plants.

In mid-summer, the spikey fruit hanging from the undersides of branches is a dead giveaway. Gooseberries are reasonably easy to identify out of season, too, as they have distinctive leaves and stems as well.

What are Gooseberries?

Gooseberries (Ribes uva-crispa) are perennial deciduous shrubs in the currant or Grossulariaceae family. You may also hear these shrubs called European Gooseberries, English Gooseberries, Goosegogs, or Feaberries.

Gooseberries are native to Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. They have widely naturalized, and the exact extent of their native range is unknown. Gooseberries often escape cultivation; today, you can find them in scattered locations in North America.

They come in a variety of colors and ripen to green, pink, yellow, red, and purple.

Are Gooseberries Edible?

Despite their fuzzy appearance, Gooseberries are edible and quite tasty raw or cooked. You can enjoy them green, though they’re quite tart, or wait until they’re fully ripened and pink.

However, you should never eat Gooseberry leaves or other parts of the plant as they contain toxic hydrogen cyanide in unknown quantities. Hydrogen cyanide is found in some other foods like almonds, and in small quantities is fine. However, it can cause respiratory failure or even death in large amounts, so avoiding the leaves is best.

Herbalists may also choose to use Gooseberries, which are safe to use internally or externally in herbal remedies.

The berries are also a fine snack for various wild birds and mammals, as well as some livestock like chickens. However, Gooseberries are toxic to dogs. The berries contain a compound called glyoxylic acid, which is digested in humans but can cause kidney problems in dogs.

Gooseberry Medicinal Benefits

We know herbalists have used Gooseberries in their remedies since the Middle Ages and probably earlier. The Roman Naturalist Pliny the Elder may have alluded to Gooseberries in his Natural History, and William Turner included it in his 16th-century Herball.

Historically, herbalists would stew the berries as a laxative or the unripe berries as a spring tonic. Though it isn’t advised today, herbalists of the past also created infusions of the leaves for treating dysentery, urinary gravel, and menstrual issues. The same infusion was also applied externally to help heal wounds as it was high in tannins.

The juice of Gooseberries was believed to help treat inflammation, and a jelly from the berries was thought to help with exhaustion, nausea, and excessive bodily fluid.

Some accounts from the Plague also mention treating patients with Gooseberries. Additionally, Gerad’s 16th-century Herball also mentions Gooseberries (referred to as Feaberries) as being good for treating ague, which describes illnesses that cause fevers and shivering.

Today, Gooseberries are primarily used as a healthy food. They’re high in antioxidants, nutrients, and fiber that may help prevent illness, keep bowel movements regular, and manage weight.

Some of those antioxidants may be critical in helping treat disease. A 2020 study on berry and leaf extracts indicated that Gooseberry’s antiviral properties may make it a good candidate for treating RSV (respiratory syncytial virus).

Nutrients in Goosberries may also be helpful for skin health when eaten or used externally. Modern herbalists sometimes use the fruit pulp cosmetically as a natural face mask. The pulp may help clean and clear greasy skin.

Some studies have also found that Goosberries may be an effective, natural treatment for children’s nocturnal enuresis or bedwetting beyond normal age.

Where to Find Gooseberry

While Gooseberry is probably native to parts of Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa, it easily escapes cultivation and has widely naturalized. It’s not uncommon to find scattered patches in North America today, and it thrives in cool regions with humid summers.

Gooseberry often grows in meadows, deciduous woodlands, mountainous areas, and rocky forests. It also thrives in disturbed and altered habitats like forest edges, parks, gardens, hedges, and fencerows.

Gooseberry produces best in full sun but will also grow in partial shade. It thrives in average soil with medium moisture in locations that are protected from strong winds. Gooseberry will grow in acidic to alkaline clay, loam, or sandy soil as long as it’s moist and well-drained.

I most commonly find wild gooseberry in wet places, alongside other plants that tolerate consistent moisture, like marsh marigold and cedar.

When to Find Gooseberry

Gooseberry shrubs can be spotted year-round. However, as Gooseberry is deciduous, it’s harder to identify in the winter. In the fall, when the weather gets cold, and other deciduous trees drop their leaves, so do Gooseberries.

In the early spring, Gooseberry begins to leaf out as other trees do. Shortly after leafing out, Gooseberry flowers, usually between May and June, depending on your climate. However, the flowers are rather inconspicuous.

Gooseberry is probably the easiest to spot and identify when it’s fruiting. Gooseberry typically fruits between July and August. You can harvest the berries at the beginning of the season when they’re green or wait until they’re fully ripe.

Since they ripen to many different colors, including green, it can be tricky to tell when they’re fully ripe, but they do get a bit softer when they’re ready.

Identifying Gooseberry

Gooseberry can be hard to spot as it is a medium-sized scrambling, unassuming shrub. It features drooping, prickly, brown, raspberry-like canes and often blends in among hedgerows and forest edges.

Each Gooseberry shrub grows multiple stems from the base and may have a spread of 3 to 5 feet wide. They usually stay under 6.5 feet tall. In the summer, Gooseberry grows simple, alternate, lobed leaves that may be dark or pale green.

The flowers can be easy to miss. They are small, light green, and bell-shaped, with five petals. The flowers give way to round berries that start green but ripen to a translucent pink-red.

Gooseberry Leaves

Gooseberry has simple, alternately arranged palmate leaves, which may be dark green or pale green and glossy or covered in fine hair. Each leaf is attached to the main stem by a petiole (leaf stem) and usually has toothed edges and 3 to 5 lobes. They may be up to 2 inches across.

Gooseberry Stems

Gooseberry typically has about 5 to 16 woody stems growing the base. The stems may be up to 6.5 feet long and often droop over, forming a wide, low shrub. The stems are brownish and covered in sharp prickles.

Gooseberry Flowers

Gooseberry flowers form singly or in small clusters of two to four. They are an inconspicuous yellow-green or greenish color with some pink or red hues. Each flower is bell-shaped and drooping and usually has five petals and five sepals that are fused at the base. They also generally have four to five stamens.

Gooseberry Fruit

Gooseberry berries are ovate to spherical. They are translucent, juicy, and usually covered in fine hair though they may be smooth. The berries start as green or yellowish-green and ripen to pink or purplish-red. On wild plants, the berries tend to be less than 0.4 inches in diameter, but they may be larger on cultivated plants.

Gooseberry Look-Alikes

The Gooseberry (Ribes uva-crispa) is sometimes mistaken for other Ribes species, including Wild Black Currant (Ribes americanum). However, Wild Black Currant differs in several noticeable ways:

- Wild Black Currant lacks prickly stems.

- Wild Black Currant typically has six or more flowers per cluster.

- Wild Black Currant berries ripen to very dark purple or black.

When not in fruit, both the western Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) and the eastern Thimbleberry (Rubus odoratus) may be mistaken for Gooseberry. However, there are a few key features that identify them:

- Thimbleberry canes may be up to 10 feet long and have reddish-brown, yellowish, or gray bark, which peels as the canes age.

- Thimbleberry leaves are soft, roughly maple-shaped, have three to seven lobes and may be up to 10 inches across and long.

- Thimbleberry flowers may be white or purplish-pink depending on the species, but both are noticeable, about ¾ to 2 ¼ inches in diameter and feature yellow centers.

- Thimbleberries are hollow-centered raspberry-like berries that ripen to red.

Ways to Use Gooseberries

The easiest way to use Gooseberries is to eat them fresh off the bush. They are a tasty, sweet, but tart snack. Raw berries make a nice addition to salads and other dishes, but if you find they’re too tart, there are some great ways to cook Gooseberries.

Gooseberries’ combination of sweetness and lemony tang makes them a go-to choice for crumbles, pies, cakes, cobblers, and fools. They also make an excellent sauce for more savory dishes like meat or fish.

Gooseberries also contain pectin, citric acid, and sugars, making them an excellent choice for jellies, jams, and chutneys. Canning one of these is a great way to put up extra Goosberries for winter! You can also preserve Gooseberries by dehydrating them for use in oatmeal, bread, and other baked goods.

These tasty berries also make for some interesting beverages. Gooseberries can be fermented into a wonderful wine, and they’re excellent in gin. In Portugal, where they’re an incredibly popular beverage, they’re mixed with soda, water, and even milk.

Gooseberries are high in fiber, antioxidants, and vitamins, so they’re a wonderful food to incorporate into your diet. They can be particularly helpful for boosting the immune system, preventing illness, lessening the symptoms of colds and flu, managing your weight, and improving your regularity.

If you don’t love eating Gooseberries, you can access those high levels of vitamins and antioxidants in other ways. Use Gooseberries to make healthy teas, infusions, tinctures, and syrups.

If you’re interested in natural skincare and can get your hands on some Gooseberries, try making a face mask. The sugars, antioxidants, and minerals in Gooseberries may help to refresh and cleanse your skin.

Gooseberry Recipes

I have a long list of gooseberry recipes that will work with both cultivated and wild gooseberries, but here are a few to get you started:

- Looking to add a foraged spin to cocktails? Try this Gooseberry Gin recipe from the BBC Good Food.

- If you’re not a gin person, they also have a recipe for Elderflower and Gooseberry Vodka.

- Craving something filling and savory, try these Pulled Pork Burgers with Gooseberry Ketchup from Delicious Magazine.

- If you want to try one of the classic Gooseberry recipes, consider this Gooseberry Fool from the Great British Chefs for dessert.

- Do you have enough Gooseberries to put some up for winter? Grab our recipe for Gooseberry Jam and start preserving!

- Or go seedless with this smooth gooseberry jelly recipe.

- Sometimes simple recipes are the best, especially after you’ve worked hard foraging. Try this Easy Gooseberry Crumble from Effortless Foodie if you want something simple and delicious.

Fruit Foraging Guides

Looking for more tasty edible wild fruit?

- Foraging Bunchberries

- Foraging Saskatoons (Serviceberries)

- Foraging Wild Black Cherries

- Foraging Chokecherries

- Foraging Aronia (Black Chokeberry)

- Foraging Barberry

- Foraging Rose Hips

- Foraging Rowanberry

- Foraging Autumn Olive

- Foraging Partridgeberry