Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

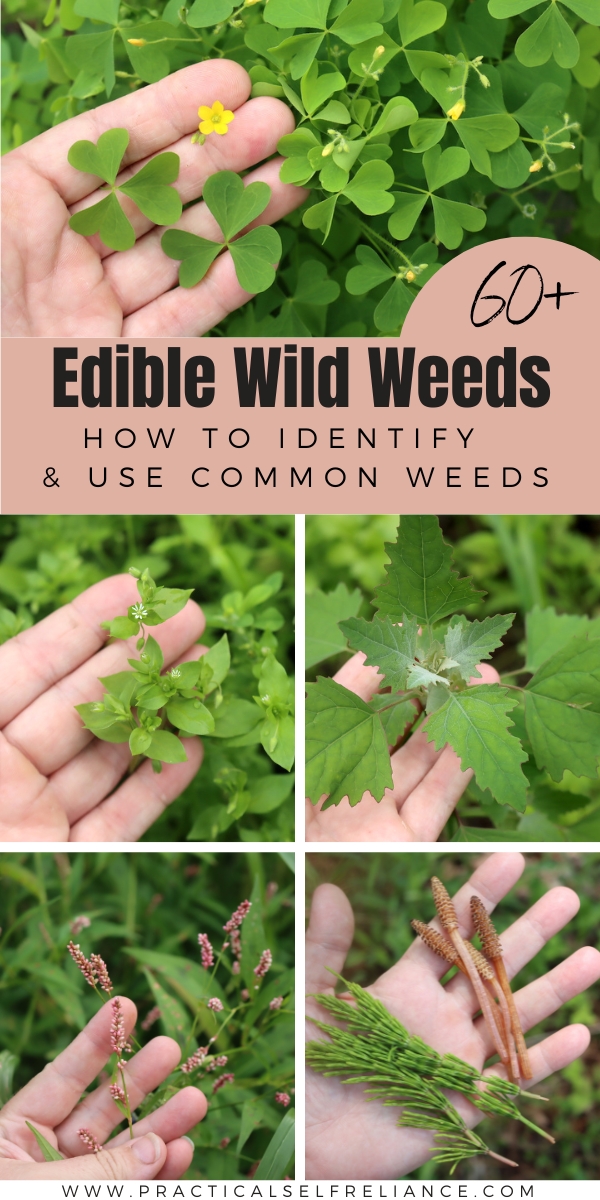

Edible weeds are everywhere, provided you know how to identify them. This list of more than 60 common edible weeds will take you through what you need to know to find, identify, and use some of North America’s most common edible, medicinal, and useful weeds.

Table of Contents

- List of Edible Weeds

- Agrimony (Agrimonia spp.)

- Bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta)

- Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- Bugleweed (Ajuga sp.)

- Burdock (Arctium sp.)

- Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare)

- Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense)

- Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

- Chickweed (Stellaria media)

- Claytonia (Claytonia perfoliata)

- Chufa (Cyperus esculentus)

- Cleavers/Bedstraw (Galium sp.)

- Clover (Trifolium sp.)

- Curly Dock (Rumex sp.)

- Crabgrass (Digitaria sp.)

- Dandelion (Taraxacum sp.)

- Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

- Goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

- Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea)

- Evening Primrose (Oenothera sp.)

- Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule)

- Herb Robert (Geranium robertianum)

- Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

- Horsetail (Equisetum sp.)

- Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

- Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- Kudzu (Pueraria montana)

- Lady’s Thumb (Persicaria maculosa)

- Lambs Quarter (Chenopodium album)

- Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

- Mallow Species (Althaea sp.)

- Melilot (Melilotus sp.)

- Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

- Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris)

- Mullein (Verbascum sp.)

- Pigweed (Amaranthus sp.)

- Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

- Plantain (Plantago sp.)

- Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium purpureum)

- Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

- Proso Millet (Panicum miliaceum)

- Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

- Quickweed (Galinsoga parviflora)

- Ryegrass (Elymus canadensis)

- Sedge (Cyperaceae sp.)

- Self Heal (Prunella vulgaris)

- Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris)

- Speedwell (Veronica sp.)

- St. Johns Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

- Stinging Nettles (Urticia dioica)

- Thistle (Cirsium sp.)

- Violets (Viola sp.)

- Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

- Wild Lettuce (Lactuca virosa)

- Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

- Wild Mint (Mentha sp.)

- Wild Oat (Avena sp.)

- Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

- Wild Strawberry (Fragaria sp.)

- Wintercress or Yellow Rocket (Barbarea vulgaris)

- Wood Sorrel (Oxalis sp.)

- Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- Other Useful Wild Weeds

- Wild Weed Foraging Guides

Wild weeds are incredibly popular with foragers, especially beginning, urban and suburban foragers. While you can spend all day in the woods hunting for wild edible mushrooms and not see a single one, weeds are everywhere! That is, in fact, what makes them weeds.

They grow and proliferate whether we want them to or not.

But just because something’s good at thriving in a sidewalk crack or neglected field doesn’t mean it’s not potentially both edible and delicious. Some of the more useful plants for humans, at least historically, were those dependable, hard-to-kill plants that grew no matter what.

Dandelions, believe it or not, were actually once cultivated for food, and the early European settlers brought seeds with them when they arrived in North America. The wheat crop might fail, but the dandelions would always be there.

It can be tricky to actually define a “weed,” and some people call invasive trees and shrubs weeds, too. For simplicity, I’ve stuck to things that are herbaceous and green, whether found in lawns, gardens, woodlands, ditches, or fields.

If you want a more comprehensive list that includes weedy trees, shrubs, tubers, and more, I’d suggest taking a look at this long list of wild edible plants.

List of Edible Weeds

I’ve tried to include every common, readily available edible weed I can find. Some of them also happen to be medicinal, and I’ve noted their properties if appropriate.

Be aware that there are literally hundreds of medical weeds that aren’t generally considered “edible,” many of which are either only used in small doses for specific conditions or they’re only used topically (like comfrey). I’ve skipped those, to focus on just the common edible weeds and ways to use them.

It’s still a very long list!

If you’re looking for a specific habitat, I have smaller guides to specific areas, including Edible Garden Weeds and Edible Lawn Weeds.

- Agrimony (Agrimonia spp.)

- Bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta)

- Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- Bugleweed (Ajuga sp.)

- Burdock (Arctium sp.)

- Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare)

- Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense)

- Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

- Chickweed (Stellaria media)

- Claytonia (Claytonia perfoliata)

- Chufa (Cyperus esculentus)

- Cleavers/Bedstraw (Galium sp.)

- Clover (Trifolium sp.)

- Curly Dock (Rumex sp.)

- Crabgrass (Digitaria sp.)

- Dandelion (Taraxacum sp.)

- Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

- Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea)

- Evening Primrose (Oenothera sp.)

- Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule)

- Herb Robert (Geranium robertianum)

- Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

- Horsetail (Equisetum sp.)

- Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

- Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- Kudzu (Pueraria montana)

- Lady’s Thumb (Persicaria maculosa)

- Lambs Quarter (Chenopodium album)

- Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

- Mallow Species (Althaea sp.)

- Melilot (Melilotus sp.)

- Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

- Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris)

- Mullein (Verbascum sp.)

- Pigweed (Amaranthus sp.)

- Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

- Plantain (Plantago sp.)

- Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium purpureum)

- Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

- Prosso Millet (Panicum miliaceum)

- Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

- Quickweed (Galinsoga parviflora)

- Ryegrass (Elymus canadensis)

- Sedge (Cyperaceae sp.)

- Self Heal (Prunella vulgaris)

- Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris)

- Speedwell (Veronica sp.)

- St. Johns Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

- Stinging Nettles (Urticia dioica)

- Thistle (Cirsium sp.)

- Violets (Viola sp.)

- Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

- Wild Lettuce (Lactuca virosa)

- Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

- Wild Mint (Mentha sp.)

- Wild Oat (Avena sp.)

- Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

- Wild Strawberry (Fragaria sp.)

- Wintercress or Yellow Rocket (Barbarea vulgaris)

- Wood Sorrel (Oxalis sp.)

- Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

I’ll take you through each of these edible weeds one by one. Many also happen to be medicinal or useful in other ways for dying, cordage, or animal fodder.

Agrimony (Agrimonia spp.)

There are several agrimony species native to North America. They’re perennial weeds with a long history of use in herbal medicine. Traditionally, people used agrimony leaves, roots, and flowers as a spring tonic, as a wash for tired feet, eyes, and inflamed skin, and as a tea for treating diarrhea, kidney issues, liver problems, and mouth and throat complaints.

Foragers primarily use agrimony in wine or other fermentations. Agrimony is high in tannins, making it a helpful addition to certain fruit wines. Tannins help prevent oxidation in wine and provide a balance of astringent or bitter flavor.

Agrimony is relatively easy to spot when it’s in flower. From a distance, it looks a bit like goldenrod as it puts on a flower spike up to 6.5 feet tall covered in yellow blooms. However, agrimony’s flowers all have five petals. It also has alternate, pinnately compound leaves.

Agrimony’s habitat varies with species, but many grow in disturbed areas. Some species, like common agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria), prefer drier habitats and grow in meadows, forest edges, pastures, and embankments. Other species like swamp agrimony (Agrimonia parviflora) tend to prefer moist habitats like bottomland forests, stream and river banks, swamps, ditches, and other moist disturbed areas.

Bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta)

Although its name doesn’t sound appealing, bittercress is a tasty little herb! It has relatively tender leaves and a mild peppery flavor. It makes excellent small greens for a salad, sandwich, or wrap. Bittercress is also healthy, loaded with vitamins C, calcium, magnesium, beta-carotene, and antioxidants. For this reason, herbalists sometimes use it as an immune-boosting herb.

Bittercress is an annual member of the Brassicaceae family. It has a fairly extensive range in moist regions of the northern hemisphere. It is a common lawn and garden weed that quickly crops up in disturbed areas. In northern regions, you’ll spot bittercress in early spring. It thrives in cool weather. It’s not uncommon to find bittercress in southern regions through the winter and spring. However, it tends not to put on significant growth during the winter.

Bittercress grows as a rosette of pinnately divided leaves with 8 to 15 leaflets. The leaflets are round to ovate with smooth to dentate edges. The leaflet at the tip is larger than those on the edges. Later, bittercress sends up stems of tiny white flowers up to three inches tall.

Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Black-eyed susans are among the most easily recognized North American wildflowers. They’re beautiful daisy-like flowers in the Asteraceae family. They have alternate, mostly basal leaves covered by coarse hairs. In late summer or early autumn, they send up branching stems of blooms with yellow petals around black, dome-shaped cones.

While they’re widely known for their beauty, fewer people realize that black-eyed susans are edible and medicinal. While the flowers, roots, and leaves are safe to use, the seeds are toxic!

You can harvest the young leaves in spring for cooked greens. Medicinally, Native Americans used black-eyed susan extensively to treat various ailments, including snake bites, colds, cases of flu, high blood pressure, ulcers, and earaches.

Black-Eyed Susans are incredibly widespread, and you can find them in all 48 contiguous US states. Look for these flowers in open and disturbed habitats like roadsides, grasslands, meadows, and prairies. They’ll tolerate clay, loam, and sandy soils. They’re tough flowers that can handle drought, but you won’t find them in soggy soil.

Bugleweed (Ajuga sp.)

This invasive perennial herb is a great medicinal and edible herb to recognize. You can eat the young shoots and leaves. Historically, herbalists used bugleweed as a tea or poultice to treat various conditions, including heavy menstrual bleeding, nosebleeds, thyroid disorders, bruises, diabetes, and more.

It can also be used as a salad green and edible flower.

There are many species of bugleweed, but most are perennial, herbaceous herbs that share a few basic characteristics. As members of the mint or Laminaceae family they all feature a square stem. They also tend to have opposite leaves and the blue or violet, trumpet-shaped flowers that give them their name.

Bugleweed grows in many eastern, midwestern, and northern states. It thrives in full sun to partial shade and frequently grows in disturbed areas. Look for it in abandoned pastures, waste places, yards, and forest edges.

Burdock (Arctium sp.)

Known for its velcro-like burs, this plant has earned a poor reputation as a nuisance weed. However, many foragers and herbalists have discovered that this unassuming plant has plenty to offer.

Foragers most commonly go after the burdock’s long taproots. While they may not look tasty, burdock roots are widely cultivated in Japan under the name “gobo.” They’re surprisingly good and have a crunchy, slightly starchy texture and mild earthy flavor. You can enjoy them raw or cooked. Burdock’s leaf and flower stems are also edible and taste a bit like celery.

Herbalists also often use the burdock roots and occasionally the leaves to create teas, tinctures, and washes. Externally, burdock’s astringency may help with eczema, rashes, arthritis, and other inflammation. Internally, herbalists generally use burdock to treat digestive issues, liver problems, and urinary conditions.

Burdock thrives in openings that receive at least partial shade. Look for it on forest edges, stream banks, trail sides, waste spaces, and lawn edges. It generally grows in moist, well-drained soil. Watch for its large heart—or egg-shaped leaves, which form a basal rosette in its first year.

Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare)

Bull thistle is a tall biennial plant covered in sharp spines. It has unique flowers with spiky bright pink florets protruding from a ball of spiky bracts or leaf like structures. Its appearance can be a major turn-off for any would-be forager. Those spines look threatening, and most field guides will warn you about the danger of a spike coming into contact with your eyes. Still, with some patience and care, plus a sturdy pair of gloves, you can forage for bull thistles.

The roots, leaves, leaf stems, flower stems, and flower buds are all edible.

I’ve found that the leaf and flower stems are the tastiest part. They are crisp, mildly flavored, and cooling. Bull thistle is related to the globe artichoke, and while its flower buds may also be tasty, I found that their small size and difficulty processing makes them not worth it to me. The roots also have decent flavor but can be a bit bitter, and the leaves are time-consuming to process due to their abundance of spines.

Generally, I think that bull thistle is most valuable as a medicinal herb. It has potent anti-inflammatory properties, and some research has found that it can be helpful in treating inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and IBS.

Bull thistle is invasive in North America and quickly colonizes disturbed areas like railroad tracks, vacant lots, and clearings. It can also become a problem for farmers and ranchers in pastures as it’s generally unpalatable to grazing animals.

Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense)

Despite the name, Canada thistle isn’t native to Canada or any part of North America. It’s native to Europe and is widely invasive. It grows about 2 to 5 feet tall and forms clusters of pink or purple flowers at the ends of branched stems. Thankfully, there are a few benefits to this spiny, perennial weed. It’s a helpful plant for pollinators and seed-eating birds like goldfinches. It’s also edible and medicinal for humans.

The leaves, stems, flower buds, and roots are all edible. However, the leaves and flower buds require tedious processing to remove the spines, so foragers generally choose the roots and stems. Herbalists also frequently harvest the roots, using them to create a tea or wash to treat diarrhea, urinary issues, fluid retention, skin rashes, and irritations.

Canada thistle invades opened disturbed areas, sometimes including moist riparian areas. Look for it in pastures, prairies, savannas, dunes, forest openings, sedge meadows, and streambanks. It can spread through areas quickly reproducing by seed and vegetatively through underground horizontal roots.

Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

You may have spotted this perennial driving down the highway this summer. Chicory has stunning bright blue flowers that emerge along the stiff, branching stems. It was brought to North America by European colonists and now commonly grows along roadsides and in waste places, blooming between spring and fall. It’s a tough plant that thrives in full sun and various soil conditions.

Chicory’s rough, hairy leaves emerge in a rosette in its first year. They’re often confused with dandelion leaves. Thankfully, they’re edible like dandelion leaves and can, though they may be bitter. The flower stems grow each summer, starting in the plant’s second year. The flower buds, flowers, and roots are also edible. One of my favorite ways to use chicory is to roast the roots as a tea or coffee substitute.

Chicory is also a highly valuable medicinal herb. The roots make both a tasty tea and a highly potent one. You may even find it in tea blends at your local grocery store, marketed to help treat sore throats and digestive issues. Herbalists believe chicory has antifungal, antiviral, antibacterial, and anticarcinogenic properties and may help treat lack of appetite, upset stomach, liver disorders, high blood pressure, cancer, and more.

Chickweed (Stellaria media)

Chickweed is one of the earliest spring greens and so easy to use. The leaves are succulent and mild and are excellent in spring salads. It earned the name chickweed because you’ll find that chickens love it, too!

Generally, I prefer using chickweed as an edible green, but it has some medicinal uses. You can crush chickweed leaves to create a soothing poultice for stings, bits, and rashes while you’re out foraging. You can also make tea from the leaves, which may help with digestive issues and have a mild laxative effect, and some people choose to preserve it in chickweed tincture.

Thankfully, chickweed is also pretty easy for beginning foragers to identify. It’s a creeping, low-growing weed that forms mats of vegetation. Chickweed features white star-shaped flowers with five petals. Each petal has a dip in the center, making it appear more like the flower has ten petals until you examine them closely.

You can usually find chickweed growing in open areas like lawns, gardens, and forest clearings. It thrives in cool, moist soil. Usually, chickweed fades as spring turns to summer, and the temperatures heat up, but you may get a second flush in fall, and in southern areas, you may find chickweed during the winter.

Claytonia (Claytonia perfoliata)

Claytonia is a succulent, annual, herbaceous weed native to the western United States and coastal areas. Look for it growing in disturbed areas. It often thrives in moist, loose soil often in partial shade.

This unassuming little weed is edible and often known as miner’s lettuce. It earned this interesting moniker when miners during the California gold rush added this plant to their diets to prevent scurvy. It’s tender and mild, making tasty additions to salads and other sandwiches.

Occasionally, herbalists also use claytonia as a medicinal herb as it may act as a mild diuretic and laxative. Herbalists also use it as a spring tonic and believe it has mild analgesic and anti-rheumatic properties. You can also use claytonia to make a soothing poultice for skin irritations.

Chufa (Cyperus esculentus)

This native sedge is a grass-like perennial that thrives in wet, sunny areas. It spreads predominantly through underground rhizomes and tubers and robs nearby plants of their nutrients. It can be a problematic weed for farmers and gardeners as it will invade moist garden beds and pastures, but it’s a favorite with some foragers!

The small tubers, sometimes called nutlets, are edible and form along the rhizomes. They have a nutty flavor, and you can use them in a range of recipes, from soups and stews to smoothies and baked goods. In Spain, a similar species is used to make a beverage called horchata, which is different from Mexican horchata.

Though primarily gathered as a culinary plant, chufa also has some medicinal uses. In Ayurvedic medicine, a traditional medicine system from India, Cyperus species are said to have aphrodisiac, carminative, diuretic, emmenagogue, stimulant, and tonic properties. They are frequently used to treat digestive conditions, including colic, indigestion, flatulence, and diarrhea.

Cleavers/Bedstraw (Galium sp.)

There are over 600 species of Gallium! They are annual or perennial herbaceous weeds, many of which are great to forage. One of the most well-known members of this big family is sweet woodruff (Galium Odoratum) or Waldmeister, “master of the woods,” which is used to flavor ice cream, cookies, tea, and May wine.

Traditionally, Germans created May wine by infusing white wine with sweet woodruff to give it a refreshing herbal flavor. This wine is used to celebrate May Day and the coming of spring. You can also use the greens of many species like cleavers (Galium aparine) for salad greens or potherb. They can be a little tough raw as they have fine, hook-like hairs but are pretty good cooked.

Most species form little fruits with similar hairs that attach to animals’ and hikers’ clothing. These fruits are also edible. Typically, foragers roast them as a coffee substitute. Herbalists also use the stems and leaves to make teas and tinctures to act as diuretics and help treat UTIs. Cleavers may also have some skin benefits for issues like psoriasis.

Cleavers have an extensive range and grow in various habitats, but they do best where they get sun. You can find them in woodland openings, farmyards, meadows, ditches, gardens, and thickets.

Clover (Trifolium sp.)

Clover may be one of the most beloved weeds. For one thing, it is an excellent nitrogen-fixing cover crop, meaning it can capture nitrogen from the air and add it to the soil, where it becomes accessible to other plants. It also produces lovely little flowers that draw the interest of pollinators and children, who can quickly learn that the little blossoms are sweet and edible. Additionally, clover is a wonderful medicinal herb.

Clover comes in many types, but the most common in North America are Red Clover (which is actually pink), White Clover, and Crimson Clover (which is a deep red).

There are many species of clover, many of which have similar medicinal benefits. Herbalists use many clovers in teas, and red clover tincture is especially popular for women’s health issues like menopause symptoms and heavy menstrual bleeding. Researchers are also exploring clover benefits for treating coughs, asthma, arthritis, and even cancer. Traditionally, herbalists have also incorporated clover into ointments for treating psoriasis, eczema, and skin rashes.

The humble clover is one of the herbs I recommend to all foragers. It’s easy to identify for beginners and comes with a host of benefits for knowledgeable foragers and herbalists. You can also find it wherever you live, whether rural or urban. Look for clover in parks, lawns, roadsides, fields, and pastures. If you have a garden, consider sowing clover as a cover crop.

Curly Dock (Rumex sp.)

Curly dock is a handy perennial plant with which to become familiar. Depending on the snow levels in your area, you can forage for it year-round. It has edible leaves, roots, and seeds.

The leaves have a tangy, lemony flavor and, when young, are good raw or cooked. Foragers mostly use the roots in herbal remedies, but you can cook them like other root vegetables or pickle them. I love using the seeds; you can grind them into a wonderful buckwheat-like dock seed flower that’s perfect for pancakes and baked goods. You don’t even need to hull them!

Curly dock is often called yellow dock because of its yellow root. The yellow coloration comes from a compound called anthraquinone, which researchers and herbalists believe has laxative effects that can be helpful for constipation and some other digestive issues. Herbalists also use curly dock as a diuretic to help treat UTIs, bloating, and urinary stones. You can make the roots into a tea or an easy-to-take tincture.

Curly dock was originally native to parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Today, it’s widespread in many regions worldwide, including North America. It’s a tough plant that you’ll find in various habitats, including ditches, roadsides, pastures, waste areas, wetlands, orchards, and wet areas. It prefers moist areas but can adapt to less moisture and will tolerate a wide range of soil types, including clay, loam, and sand.

Crabgrass (Digitaria sp.)

Many people are surprised to learn that the dreaded crabgrass produces a wild edible grain that can be ground into flour, cooked in stew, or fermented into beer. During the Middle Ages, Slavic peoples in Eastern Europe cultivated one of the crabgrass species, commonly called hairy crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis). They typically cooked the grain in soups and porridges. People in Germany and Poland still sometimes cultivate this species, which has earned the plant the nickname Polish millet.

Crabgrass includes annual and perennial grass species that can now be found nearly worldwide, in part because of its value as a grain and animal fodder. Colonists brought crabgrass to North America. They valued the plant because it’s exceptionally hardy, drought-resistant, smothers other weeds, is a relatively high protein fodder, and produces grain throughout the summer.

You can find crabgrass species growing temperate, subtropical, and tropical regions worldwide. It thrives in highly disturbed, open areas. Look for crabgrass growing in lawns, gardens, prairies, vacant lots, fields, waste areas, roadsides, edges of degraded wetlands, and railroad grades. Crabgrass is very adaptable to poor soils.

Dandelion (Taraxacum sp.)

Dandelion might be one of the most widely recognized wild foods. You can eat this perennial herbaceous plant’s leaves, crowns, flowers, stems, and taproot. Many beginner foragers go for the leaves, but I think they’re generally overrated compared to other wild greens. However, their crowns are delicious, and you can use the cheerful yellow blossom to decorate baked goods or make wine. Some people use the flower buds as a caper substitute.

The taproots are a great herbal remedy. You can use them roasted as a coffee substitute, in teas, or as a tincture. New research has found that dandelion may have some antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties.

There are many species in the dandelion (Taraxacum) family, many of which have naturalized worldwide. Dandelions are incredibly common and a good option even for urban foragers. Dandelions thrive in open areas with rich, moist soil, but they’ll also tolerate much more arid, poor habitats. Watch for dandelions in parks, lawns, pastures, fields, and empty lots. Avoid harvesting any that may have been sprayed or contaminated with chemicals.

Since dandelions are so common and useful, I have a number of guides for identifying and working with them:

- Identifying Dandelions

- 12+ Dandelion Lookalikes

- 50+ Dandelion Greens Recipes

- 50+ Dandelion Flower Recipes

- 12+ Dandelion Root Recipes

- 12+ Dandelion Seed Recipes

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

Garlic mustard is a biennial flowering plant in the mustard family. It’s native to parts of Europe and Asia but was brought to North America by settlers in the 1800s who used the plant for its medicinal properties and erosion control. Since then, garlic mustard has become a destructive invasive that blocks light and steals nutrients from early spring woodland natives. Unfortunately, it seems to be strengthened by climate change.

Luckily, garlic mustard is edible!

As foragers and herbalists, we can help keep this plant under control. You can harvest the leaves and roots. Some foragers find that the roots are similar to horseradish. Young leaves are best and have a bit of punchy, garlicky mustard-greens flavor. You can eat older leaves, but they tend to be bitter and contain cyanide, so you will need to boil them to eat them safely.

Through the ages, herbalists have used garlic mustard internally and externally. It may have antiseptic properties; you can use it as a tea, tincture, or poultice. It’s also rich in vitamins A, B, C, and E.

Garlic mustard may grow in open areas, but it’s also shade tolerant and can grow in the forest understory. Look for it in savannas, roadsides, upland forests, floodplain forests, trail edges, and disturbed areas. It thrives in moist, loamy soil.

Remember, garlic mustard isn’t a sensitive native herb we’re worried about harvesting; it’s a destructive invasive. Try to pull all the plants up by the roots and destroy and burn any material you don’t eat.

Goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

In late summer and autumn, goldenrod graces roadsides, fields, forest edges, prairies, and meadows across the United States with its spikes of golden flowers. Though it’s often blamed for allergies caused by ragweed, foragers, and herbalists recognize this beautiful plant as a true herbal ally.

Traditionally, herbalists used goldenrod for its anti-inflammatory properties. This cheerful plant may help treat UTIs, arthritis, gout, liver issues, sinus infections, allergies, colds, flu, and asthma. It makes a wonderful tea or tincture—definitely my go-to for UTIs! It’s also a tasty edible green, though a bit strongly flavored. I like to harvest the shoots and growing tips.

Goldenrod is easiest to identify when it’s in flower. Thankfully, this is also a good time to forage for this plant. The flowers are best for medicinal tinctures and teas when they have just begun to open. There are about 150 goldenrod species, most of which are native to North America. Many of these species are extremely difficult to differentiate, even for expert botanists. Thankfully, all of these faithful bright herbs are safe to use and seem to share the same properties.

Look for goldenrods’ slender, erect stems with golden flowers spiraling or alternating along the upper portion, sometimes branching into smaller sections. Goldenrods are part of the Asteraceae or Aster family, and each tiny flower head is composite, much like a dandelion or sunflower. The leaves are narrow and lance-shaped or almost grass-shaped with pointed tips, and they alternate along the stem.

Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea)

You’ve probably spotted this herbal ally before without realizing it. Ground ivy, sometimes called creeping charlie, is an herbaceous evergreen perennial in the mint family that has naturalized in North America. It grows along the ground and features tiny purple flowers and hoof or kidney-shaped crenate leaves. When you crush or mow it, it has a distinct herbal or minty aroma.

Ground ivy has a fairly strong and bitter flavor, so I like to use small amounts in soups, salads, and other dishes. Today, ground ivy is probably most widely used as a medicinal herb. It may have anti-inflammatory properties and is a rich source of vitamin C, potassium, and iron. You can incorporate ground ivy into herbal teas and tinctures.

Historically, ground ivy was commonly used in brewing, especially before hops became widely available. It was also occasionally used as a substitute for rennet, a substance that comes from the stomach lining of young animals and curdles milk in cheesemaking. Traditionally, rennet was obtained by killing one of the farm’s young calves. If this wasn’t available or ideal, farmers sometimes turned to vegetarian sources like ground ivy.

Ground ivy commonly grows in lawns, fields, gardens, and woodland edges. It thrives in areas with full sun or partial shade and rich, moist soil. In ideal habitats, ground ivy quickly spreads to cover huge swaths of ground, outcompeting other weeds.

Evening Primrose (Oenothera sp.)

Evening primrose is a native, herbaceous biennial with bright yellow flowers. It’s among my favorite edible weeds because it’s edible from root to tip and helps fill gaps in the foraging calendar when little else is available. You can harvest the roots and leaves in early spring, the flowers throughout the summer, and the seeds in fall and winter.

Modern medicine has focused primarily on primrose oil, but historically, herbalists have used all parts of the plant to treat various conditions. Recent research has indicated that evening primrose may help treat menstrual problems, menopause symptoms, and atopic dermatitis. You can make teas, tinctures, and poultices with evening primrose.

Many evening primrose species are early colonizers of disturbed areas. You can sometimes find them in waste areas, dunes, railway embankments, old fields, lawn edges, and roadsides. Evening primrose thrives in loose, gravelly, or sandy soil but isn’t particular and will tolerate a wide range of soil types.

Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule)

Henbit is among the common, advantageous annual weeds that quickly pop up in sunny, disturbed areas worldwide. Originally native to the Mediterranean, henbit was probably introduced to North America in the 1700s by ships that carried it amongst ballast and livestock feed.

You have likely seen henbit before, and once you know what to look for, it’s pretty easy to identify. Henbit has a low-growing, somewhat sprawling habit. It features scalloped leaves that look a bit like they have been pecked on the edges by a bird and purple or pink tubular flowers. Generally, you spot henbit in the spring or fall as it thrives in cool weather.

It’s a wonderful herb to find. Henbit is in the mint family and, like many other mints, is entirely edible. You can gather fresh henbit leaves, stems, flowers, and seeds for use in salads, soups, stir-fries, or even baked goods. Herbalists frequently use it in teas, tinctures, and poultices as it may have significant antimicrobial, antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant properties.

Look for henbit in disturbed areas that receive full sun, like lawns, gardens, parks, pastures, railroad and road edges, and vacant lots. It’s a pretty easy herb to find, even in urban areas! It thrives in mildly acidic to neutral soil.

Herb Robert (Geranium robertianum)

This annual or biennial weed is in the Geranium or Geraniaceae family. It’s a distinctive sprawling plant with fern-like leaves that often take on a red tinge in late summer and fall. Over the years, it has acquired many unusual common names, including Stinky Bob, Fox Geranium, Red Robin, Death-Come-Quickly, Squinter Pip, and Bloodwort.

Many of Herb Robert’s common names refer to its various historical medicinal uses and superstitions. Thankfully, we know today that it’s a largely beneficial weed. Though Herb Robert is edible, it’s primarily used medicinally as it often has a pungent, slightly spicy taste and intense fragrance when crushed.

Researchers have found that Herb Robert may help lower blood sugar, treat diarrhea, reduce inflammation, and fight infections and cancer. Its intense flavor makes it a good choice for tinctures, which are easy to take. However, you can also use it in tea and external preparations.

Herb Robert prefers habitats with moist soil and full to partial shade, but it is quite adaptable and sometimes grows in drier, rockier, sunnier areas. Look for Herb Robert in woodlands, parks, hedgerows, coastal areas, railway lines, gardens, and rocky slopes.

Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

Sometimes called Indian Jewelweed, Himalayan Balsam is the invasive cousin of our native Spotted Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) and Pale Jewelweed (Impatiens pallida). It’s native to the Himalayan region of India, Pakistan, and Nepal, but it has aggressively spread throughout much of North America, Europe, and New Zealand. It’s a large plant with lanceolate leaves and showy, pink helmet-like flowers that quickly forms dense colonies.

Thankfully, there are several ways we can put this edible invasive to good use. You can eat the leaves, young shoots, flowers, and seed pods. The seeds have great flavor and are a traditional ingredient in Indian curries. The pleasant blossoms are excellent additions to baked goods, or you can ferment them to create a champagne-like beverage.

Himalayan balsam is also medicinal. Like our native jewelweed, it’s great for soothing poultices to relieve pain and itching from nettle stings, insect bites, poison ivy, and other skin irritations. One of my favorite ways to use it is to freeze it as ice cubes to cool sunburns and other minor burns.

Himalayan balsam primarily grows in moist, nutrient-rich soil. It often quickly colonizes recently disturbed areas and tolerates full sun or partial shade. Look for it in riparian areas, ditches, marsh edges, streambanks, forest margins, thickets, and wet waste areas during the summer.

Horsetail (Equisetum sp.)

These plants are living fossils! They are the only remaining genus in an order of plants called Equisetales, which dominated Earth’s Paleozoic forests for about 100 million years. These unusual plants send up fertile, short-lived whitish or brown stems with spore-producing cones on the top in spring. After these wither, they form green shoots with whorls of leaves that look a bit like miniature pine trees.

Aside from being interesting and enjoyable to look at, horsetails are edible, medicinal, and downright useful. The fertile shoots may not look appetizing but they’re a surprisingly delicious vegetable. Herbalists prefer the sterile green stem that comes up later, using it to create teas, tinctures, and ointments. Horsetail plants are rich in silica and has antimicrobial properties, so it may help with bone density, wound healing, osteoporosis treatment, and cartilage repair.

Horsetail’s other common names, like scouringrush and scourweed, hint at its other uses. The plant’s high silica content makes it an ideal scrub brush for polishing wood and metal and cleaning pots, pans, and other surfaces.

Horsetails have an extensive range, so it’s likely you’ll be able to find some near you. These plants thrive in many of the same areas as ferns. Look for them in areas with moist, soft, alkaline, or neutral soil. Occasionally, you can also find them in more acidic soil and drier areas.

Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

Japanese knotweed is one of the few wild edibles that I wish everyone would harvest. In the United States, it’s a vigorous, invasive perennial that forms dense colonies and chokes out native vegetation. Unlike our sensitive native herbs, this wild weed is one you can harvest to your heart’s delight, and it’s tasty!

Japanese knotweed often forms dense thickets along roadsides and streambanks. It thrives in moist soil and is often spread by mowing and flooding because chunks of knotweed can root to form new patches. It has bamboo-like hollow stalks with pinkish divisions and large heart-shaped leaves.

I love harvesting the young shoots that come up in the spring, a bit like I’m picking asparagus. They have delicious rhubarb-like flavor and make great additions to crisps, pies, and other desserts. Herbalists, traditionally harvest the roots and rhizomes for teas and tinctures to treat viral infections, coughs, and other ailments.

Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

This one is easy to pick out with its almost translucent stems, bluish-green leaves, nodding orange flowers, and explosive seed pods. Jewelweed is edible as a green, but this beloved plant actually gets a lot of attention as a medicinal. You can crush the leaves to make a quick on-the-go poultice that helps relieve insect bites, stings, poison ivy, sunburn, and other skin irritations. While many hikers and foragers know how to use it this way, fewer realize that it is edible.

Jewelweed seeds have a tasty walnut-like flavor, and the beautiful orange blossoms add natural color to baked goods and salads. You can also eat the young stems and leaves, but they’re high in oxalic acid so it’s best to boil them in two changes of water. Older leaves and stems have even higher oxalic acid content and should be avoided.

Jewelweed is a native annual of North America. It grows in moist, shady areas, often forming dense patches. It’s common in wooded lowlands, especially in disturbed areas like roadcuts and ditches. It also grows along lakes, streams, wetlands, and bogs. Jewelweed does best in soil with a neutral or acidic pH.

Kudzu (Pueraria montana)

The vine that ate the South. During the Great Depression in the 1930s, the Soil Conservation Service promoted kudzu in the United States as a great option for erosion control. At the time, members of the Civilian Conservation Corps were tasked with planting the vine, and farmers were incentivized up to $8 per acre to plant kudzu.

Unfortunately, one thing that makes kudzu great at controlling erosion is its speed. Kudzu can grow up to one foot per day and as much as 60 feet in a single season. It quickly became invasive and still creates patches where it has choked out native vegetation and created vine barrens.

Kudzu was and still is appealing in other ways. This perennial vine has been used as livestock fodder, food, medicine, and to make paper, fiber, and basketry. In Japan, kudzu starch from the roots is still an important ingredient in confections and sweets. You can also use the starchy roots to make flour and pasta. Additionally, the leaves are good raw or cooked. Kudzu is also important in Chinese medicine for treating high blood pressure, anxiety, heart disease, and menopausal disorders. It may counteract the effects of alcohol.

If you’re looking for kudzu, you can recognize it by its brown rope-like vines, trifoliate leaves with two to three lobes, and tuberous roots. Kudzu loves disturbed habitats that offer plenty of sunlight. Look for it in abandoned fields, forest edges, vacant lots, roadsides, and waste places.

Lady’s Thumb (Persicaria maculosa)

These flowering, annual weeds are members of the buckwheat family with thin, lance-shaped leaves and spikes of pink flowers. They often form dense patches, crowding out other weeds, and have pink flower spikes that give way to edible seeds that mature to dark brown. You can also eat the young shoots, leaves, and flowers. They contain some oxalic acid, which gives them a lemony flavor.

Herbalists also use lady’s thumb in medicinal preparations. Typically, they use the leaves, stems, and flowers in teas, tinctures, and poultices. Some research indicates that a lady’s thumb may be valuable in helping treat liver problems, bacterial infections, and parasites.

Lady’s thumb has an extensive range and grows worldwide. It does best in disturbed habitats with relatively moist soil and full sun. Look for lady’s thumb in fallow fields, streambanks, ditches, roadsides, and damp yards.

Lambs Quarter (Chenopodium album)

Easy to identify and easy to use, lamb’s quarter has to be one of my favorite weeds for beginner foragers. Its greens are tasty and mild, earning it the nickname, wild spinach. In Nepal and India, people extensively cultivate this food crop called bathua. Lambs quarter also produces edible grain, which has a long history of being used as a staple crop. Archeologists have found evidence that people ate the lambsquarter seeds at Iron Age, Viking Age, and Roman sites in Europe. They have also found them mixed in the stomachs of Danish bog bodies.

Lambs quarter also has a history of medicinal use in herbal medicine, such as Ayurveda, a system of Indian traditional medicine. Many herbalists believe it may be useful in teas and tinctures for treating diarrhea, stomach upset, and loss of appetite. Lambs quarter is also an excellent animal fodder.

If you’re a gardener, there’s a good chance you’ve spotted lambs quarter before. It’s a fast-growing annual that loves disturbed areas and frequently pops up in gardens. Even if you don’t garden, you should be able to find some. Lambs quarter frequently grows on roadsides, trailsides, fields, vacant lots, streambanks, and other areas where it will receive full sun.

Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

This low-growing perennial is a member of the buttercup or Ranunculaceae family and features the classic, cheerful yellow flowers. It is native to Europe, western Asia, and North Africa but has become invasive in parts of the United States, making it a great plant for foragers to seek out.

Foragers in central Europe commonly harvest the young leaves as a potherb, though some people find them bitter. The plant also produces intriguing fleshy underground tubers, which have given it one of its common names: pilewort. The tubers are thought to resemble hemorrhoids or piles. Thankfully, these roots don’t live up to their name and actually have pretty good flavor.

Probably due to its appearance and the doctrine of signatures, an old philosophy that plants looked like the body part they healed, historically, herbalists made ointments from lesser celandine to treat hemorrhoids, corns, and warts. There are also some English records of people using the leaves to clean their teeth.

Lesser celandine isn’t picky about its habitat. You can find it growing in woodlands, roadsides, wetlands, streambanks, landscaped areas, lawns, and riverbanks. It thrives in moist sandy soil and can tolerate full shade to full sun.

Mallow Species (Althaea sp.)

You’re probably already familiar with a couple of the perennial or biennial herbaceous herbs in this genus. Hollyhocks (Althea rosea) are common ornamental flowers, and marshmallow (Althea officinalis) is an essential medicinal weed and was once a key ingredient in the fluffy white confections bearing its name. All Althea species are edible in their entirety. You can use the seeds, leaves, young stalks, flowers, and roots raw or cooked.

When they gather Althea species, most foragers and herbalists seek the mucigenous roots. Both historical documents and modern research support using these roots to treat sore throats, coughs, and other respiratory ailments. In fact, the marshmallow confections we know today probably started as a cough remedy. The roots also help heal burns, skin irritations, and minor wounds.

While Althea species aren’t native to the United States, some, like marshmallow (Althea officinalis) are fairly easy to find here. They’re probably easiest to spot when they’re in flower with their showy, hibiscus-like pink or white blooms. They also have fuzzy stems and hairy upper surfaces of their heart-shaped or ovate leaves, which can help you identify them.

These species generally thrive in full sun and consistently moist soil. As the name marshmallow suggests, you can often find them growing in marsh margins, streambanks, brackish wetlands, ditches, and other wet, open, or disturbed areas.

Melilot (Melilotus sp.)

The name melilot covers about 19 species of annual biennial weeds. They’re sometimes referred to as sweet clovers because they have a distinct, sweet aroma and share true clover’s trifoliate leaves. However, melilots tend to be larger, more upright plants with narrower, toothed leaflets. In summer, you may spot spikes of white or yellow flowers.

Traditionally, foragers have used melilot’s edible greens and flowers for both culinary and medicinal purposes. Modern research has supported some herbalists’ uses, indicating that melilots may have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anti-tumor properties. People have also used this pleasantly fragrant herb to deter moths and other pests from woolens and linens.

Some herbalists like to dry melilot for later use. However, melilot contains coumarins. When improperly dried or exposed to humidity, these coumarins are converted to dicoumarol, a potent anticoagulant that can cause hemorrhaging in people and animals. Avoid melilot if you’re taking warfarin or have issues with blood clotting.

Melilot is native to Europe and Asia, but many species have naturalized in the United States. It’s a grassland species that’s tolerant of poor soil. You’ll find it in disturbed areas with full sun and clay or loamy soil, like prairies, pastures, roadsides, fields, gardens, and savannas.

Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Most people think it’s crazy to forage for milkweed! People I have talked to are either afraid that it’s poisonous or that we’re stealing from the monarchs and other butterflies. I’ve found that neither of these is true. Milkweed is perfectly safe when harvested and prepared correctly. I’ve also noticed that folks are much more likely to recognize, tend, protect, or even plant milkweed once they realize how tasty it is. So, I think it’s time to spread the word about this awesome plant.

Milkweed is one of my favorites because it offers a tasty edible product at each stage. In the spring, we harvest the tender shoots like asparagus. Don’t worry, they resprout, and when they flower, you can harvest a few young flowerheads like broccoli. If you leave a few for the bees, the flowers produce edible, okra-like young seed pods. Later, the immature seeds make a wonderful vegan cheese substitute.

I mainly focus on common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), but there are about 73 species that are native to the United States. Common milkweed and the other species are incredibly important. Over 450 species of native insects feed on its nectar, sap, leaves, and flowers. Getting in touch with these plants can help us protect them!

While the habitats of the other species vary significantly, common milkweed thrives in open, sunny, disturbed habitats. Look for it in your garden, along fencerows, roadsides, fields, and pastures.

Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris)

With common names like felon herb, riverside wormwood, sailor’s tobacco, and naughty man, you know that mugwort has a long and colorful history. Over the centuries, people have used mugwort as an offering to the gods, stir fry ingredient, aromatic herb, and bittering agent in ales. Adventurous individuals have also used mugwort as a smoking herb and in tea to promote lucid dreaming. Mugwort contains thujone, the same compound found in wormwood and traditional absinthe recipes.

However, mugwort may not be the bad actor it’s often portrayed as. It’s also known as the “mother of herbs.” It has played an important role in traditional Hindu, European, and Chinese medicinal practices. New research has found that it may have antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, antispasmodic, and antihypertensive properties.

Mugwort is a herbaceous perennial that sometimes reaches 6 feet tall. It spreads aggressively through underground rhizomes and has distinctive chrysanthemum-like, pinnate foliage with white hairs on their undersides.

Mugwort is native to parts of Europe, Africa, and Asia but has naturalized widely in the United States. In some areas, it’s considered invasive and will quickly colonize disturbed areas with low-nitrogen soil. Look for it in fields, waste places, roadsides, and other open areas.

Mullein (Verbascum sp.)

This friendly weed is easy to recognize and use. It’s an incredibly useful edible and medicinal herb. The leaves, flowers, and roots of mullein are all edible. I prefer eating the tasty taproot and using the flowers in salads and garnishes. The fuzzy leaves are edible but best for medicinal use.

Medicinally, mullein is an essential herb as a tincture and tea for treating coughs and other respiratory ailments. Herbalists have also used the herb externally to treat skin issues like sunburn, sores, rashes, and back pain. Modern studies have shown it may have antiseptic properties against pneumonia, staph, and E. Coli bacteria.

Mullein is a biennial, and it’s easy to miss it in its first season. It grows as a basal rosette of velvety, light green, ovate leaves up to one foot long. This stage is a great time to harvest the taproots, and you can collect the leaves. You won’t find the flowers until the second season when mullein sends up a 2 to 7-foot tall stem that may be so wooly it appears white.

Mullein thrives in full sun and poor, well-drained soils. It tends to quickly colonize disturbed areas. Look for it on roadsides, ditches, forest clearings, pastures, and meadows.

Pigweed (Amaranthus sp.)

Pigweed doesn’t sound tasty, but it actually got its name because it makes tasty fodder for pigs. Thankfully, this weed is tasty for humans, too! Pigweed refers to several wild amaranth species native to the United States.

Many farmers and gardeners consider pigweed a major nuisance, but its leaves, roots, and seeds are all edible. Historically, it was an important crop for Native Americans, particularly in the Southwest and Central America. It was an essential grain crop for the Aztecs. Amaranth is also used medicinally, though there hasn’t been much modern research on it.

Pigweed is an annual, herbaceous weed that can quickly reach about 6 feet tall. It has many branches with simple, oval to diamond-shaped alternate leaves. The flowers grow in densely packed clusters near the top of the plant.

Pigweed is incredibly common; if you’re a homesteader or avid gardener, you have probably already seen it. Pigweed loves to colonize patches of bare soil in full sun. This summer, watch for it popping up in your garden, waste places, and pastures, particularly around feed and water troughs where there is bare soil.

Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea)

Pineapple weed is often among young foragers’ first ventures. Like dandelions and blackberries, it’s pretty easy to find and identify. Pineapple weed is an invasive perennial with a propensity for growing in poor compacted soil. This makes it a great option for urban and suburban forages, but if you’re on lush farmland, you’ll need to look around compacted areas like gate, barn, and garage entrances.

It’s worth looking for, too! The petalless flowers have a slightly sweet, chamomile, pineapple-like flavor, making them a delicious addition to herbal tea and baked goods. Some people also harvest the greens as a salad green before the plants bloom. I find them too bitter after the plant has flowered.

Pineapple weed is also medicinal and may offer some of the same benefits as chamomile such as soothing indigestion, relieving anxiety, and helping reduce fevers. Pineapple weed is in the same family as chamomile, Asteraceae.

You won’t have any trouble identifying pineapple weed. It has unique pinnate, fern-like leaves and yellowish-green, cone-shaped flower heads that lack petals. If you have any doubt, it’s pineapple or chamomile-like aroma is apparent if you crush some in your fingers.

Plantain (Plantago sp.)

Many kids recognize this edible weed as frog leaf or bandaid plant. Its use as a quick poultice for scrapes, insect stings, and rashes makes it an invaluable plant for children or adults enjoying their summer outdoors.

Plantain’s other properties are less well-known. I’ve found that it’s a useful plant to make into medicinal preparations, like plantain tincture and plantain salve. Modern studies have confirmed plantain’s helpfulness in healing wounds on the inside and shown that it can help treat internal inflammation from respiratory and digestive ailments.

Plantain is also edible. I find that the leaves are best when they’re young, small, and not too bitter. However, some Europeans use the larger leaves to make dolmas. The seeds are also edible and are excellent toasted and ground into flour or cooked as porridge.

Generally, I find broadleaf plantain (Plantago major) and narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata) to be the most common and widely recognized, but there are about 200 species of plantain. They’re cosmopolitan weeds that are generally easy to find in open, disturbed habitats. They tolerate poor soil, and you can find them in lawns, gardens, parks, roadsides, and pastures. Depending on the species, plantains have broad or narrow leaves with three or five parallel veins. They send up relatively tall flower spikes that lack leaves and feature tiny flowers.

Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium purpureum)

Purple dead nettle may be just a weed, but it’s a symbol of spring for foragers.

It thrives in the cool, moist weather of early spring, carpeting sections of your lawns, gardens, or pastures with moist, fertile soil. Its pinkish-purple top leaves that descend to green are a welcome sight! This plant is delicious and medicinal, and the bees love its purple, tubular flowers, too.

This plant’s name probably comes from its heart-shaped or triangular leaves that are thought to resemble stinging nettle. However, its lack of sting and square-shaped stems give it away as a member of the mint family. It’s an excellent green for spring pestos, soups, and omelets.

Medicinally, the leaves are antibacterial and can be used to stop bleeding, much like yarrow. It’s great for salves for minor wounds and irritations. It’s also an immune-boosting herb and could help with digestive issues, making it a suitable choice for teas and tinctures.

Gather purple dead nettle while it lasts! It fades quickly as spring gives way to summer and the temperature rises.

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

Purslane’s succulent leaves and stems look more like plants you’d find in hot, tropical climates than in New England, but this plant has an extensive range! In its native range, purslane is a perennial, but in cooler climates, it thrives as an annual. It grows in all U.S. states except Alaska and is considered invasive in the southwest.

Worldwide, many people grow purslane in their vegetable gardens. There are about 40 cultivars, and people grow them for soups, stews, salads, and tomato sauces. Thankfully for foragers, this weedy plant tends to crop up in gardens, disturbed areas, sidewalk cracks, gravel driveways, and waste places.

Purslane tastes a bit like spinach combined with a sour or lemon-like flavor. It’s excellent fresh, or when added to soups and stews, its mucilaginous leaves and stems will act as a thickener. You can also eat the little black seeds or use them for tea. Modern studies on purslane’s medicinal benefits are limited, but it has played an important role in traditional medicine. It may be helpful in treating diabetes, cancer, parasites, coughs, and musculoskeletal pain.

Purslane is easy to identify. It’s a low-growing sprawling plant. The reddish stems and small green leaves are conspicuously succulent, containing about 93% water. That said, be sure of your identification. In the past, Inexperienced foragers mistook this plant for deadly spurges (Euphorbia spp.).

Proso Millet (Panicum miliaceum)

Proso Millet is an important grain crop that was probably originally cultivated in eastern Asia about 10,000 years ago. Today, it remains a common crop in many places, like the midwestern United States, thanks to its drought tolerance and quick growth. In the United States, a weedier wild proso millet has escaped cultivation and spread throughout the states.

Proso millet thrives in full sun and will handle a range of soil types and moisture levels. It’s common in croplands, waste sites, roadsides, gardens, and other areas with disturbed soil. Its seedlings are easy to mistake for corn seedlings.

When proso millet matures, it can reach up to 3.5 feet tall. The stems are covered in stiff, short hair and feature alternate, grass-like, arching leaves up to 1 foot long. A drooping seed head up to 1.5 feet long forms at the top of the stem. Domesticated varieties tend to have yellow or light brown seeds, while wild varieties usually have brown or black seeds.

You can use proso millet seeds similarly to other grains. In Mongolia and parts of China, it’s often made into a fermented porridge called “suan zhou.” Here in the United States, it’s often used to make gluten-free beer and as a feed for chickens, pigs, and wild birds. However, it’s deficient in lysine, so it shouldn’t be a main food source for livestock without supplementation.

Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

Foragers know that Queen Anne’s Lace happens to be one of the world’s most widespread weeds, though it can be tricky to identify with all the other weeds with white flowers out there. You may have heard this biennial or perennial plant referred to as wild carrot because it is the same species as a domesticated carrot. Like the domestic cultivars, this species has edible roots, greens, flowers, and seeds.

The roots are one of my favorite parts to use. They taste a lot like carrots but are only good to harvest in their first year. Like the carrots in your garden, they become tough and woody as the plant grows into its flowering season. I use the leaves as a potherb or in pesto, and the flowers make excellent fritters. The seeds have a nutty flavor well-suited to baked goods but are generally used medicinally. Historically, these seeds were used as a contraceptive, so it’s important to avoid them if you’re pregnant or breastfeeding.

Look for Queen Anne’s lace in dry, sunny, open, and disturbed habitats like fields, meadows, roadsides, and waste areas. In its first year, it has a basal rosette of pinnate, carrot-like leaves. In its second year, it puts up a flower stalk with a flat-topped cluster of tiny white flowers often featuring one red or purple spot in the center. It’s said this is where Queen Anne pricked her finger while sowing the lace.

Queen Anne’s lace does have a few toxic lookalikes, namely poison hemlock and water hemlock. Identification should be taken seriously, as both of these plants can be deadly! One key identifier is that both hemlocks have reddish or purplish mottling on their smooth stems, while Queen Anne’s has a hairy green stem. A great way to remember this is that the ladies in Queen Anne’s time had hairy legs. Carefully study all the ways to tell these plants apart and make sure you are 100% certain of your identification.

Quickweed (Galinsoga parviflora)

Many gardeners, homesteaders, and farmers will recognize quickweed as a warm season annual that can quickly take over a garden. Its fast germination, growth, and re-seeding can make it an incredibly difficult weed to control, particularly in vegetable and cut-flower production spaces. Thankfully, quickweed has a few redeeming qualities. Quickweed is edible in its entirety and has a few medicinal uses.

Quickweed is delicious and tender before it has flowered. I love using it in pesto, salad, smoothies, soups, and stir-fries. It’s a key ingredient in a tasty Colombian soup called Ajaco. Medicinally, people frequently use quickweed as a poultice; some studies have shown that it may help heal minor wounds and irritations. Internally, it may help treat certain blood issues.

Once you learn to identify quickweed, you’ll probably start seeing it everywhere. It’s a slightly hairy, branched herb that can grow about 30 inches tall. It has opposite egg-shaped or triangular leaves and tiny flowers with central yellow discs and three to eight widely spaced petals.

This summer watch for quickweed popping up in areas with disturbed soils like gardens, croplands, lawns, and even container gardens.

Ryegrass (Elymus canadensis)

Ryegrass is a wonderful, native prairie grass that helps to stabilize soil. It’s a short-lived perennial species that produces spiked seed heads of oat-like seeds with bristly awns. The seeds are edible, but you must process them to remove the hulls and awns.

Traditionally, the Paiute harvested these seeds and processed, parched, and ground them to create a fine meal or flour called pinole. They used pinole to make porridge, drinks, and cakes.

Little is known about any potential medicinal uses of ryegrass. However, some records indicate that the Haudenosaunee used a decoction of the roots to treat kidney ailments. They also made a decoction of wild rye and several other plants, which they soaked their corn seed in before planting.

Ryegrass grows in open, sunny areas. Look for it in meadows, open woodlands, ditches, verges, depressions, grasslands, and fencerows. It thrives in moist, well-drained soil and will tolerate loam, sand, or clay.

Sedge (Cyperaceae sp.)

The sedges or Cyperaceae family includes more than 5,500 known species that grow all around the world! Many of these species thrive in wetlands and poor soils, often becoming agricultural weeds. For the traveling forager or anyone interested in survival skills, sedges can be a helpful plant to recognize.

Some sedge species, like the yellow nutsedge or chufa (Cyperus esculentus) we discussed above, are incredibly tasty! Other species aren’t high on my foraging priority list but are still edible if not choice. Most members of the sedge family are edible and have starchy roots that are a bit like cattail roots, though some are too woody to enjoy. A few species, like papyrus (Cyperus papyrus), also have a tall stem containing an edible pith.

Many sedge species also have strong, fibrous stems and leaves. Worldwide, several cultures have used these species to weave hats, baskets, mats, sandals, and even small boats!

To the untrained eye, sedges look just like grass or rushes. Thankfully, there’s a simple way to distinguish them. Almost all sedge species have a triangular cross-section. There are just a couple of exceptions to this rule. Sedge leaves are also spirally arranged, while grasses have alternate leaves.

Look for these species growing in open areas with moist soils, such as meadows, wetlands, croplands, pastures, riverbanks, and gardens. In favorable habitats, these species can become dominant, creating what’s known as sedge meadows or sedge lands.

Self Heal (Prunella vulgaris)

As you have probably already guessed from its name, self heal is a potent medicinal herb. Traditionally, people have used self heal as a tincture, poultice, and salve to treat various conditions.

Self heal is one of my favorite herbs to use in poultices and salves as it speeds wound healing. I also love making self heal tincture, which can be helpful for boosting the immune system to fight off colds and flu. Self heal is also an edible herb but it can be bitter so I use it sparingly.

Self heal is a creeping herbaceous perennial in the mint family. It features square, reddish stems with oppositely arranged ovate or lance-shaped leaves. During the summer, it produces small purple, tubular flowers in whorls on club-like spikes. As it can propagate underground through its rhizomatous roots it often forms dense patches that are striking in bloom.

Look for self heal growing in gardens, lawns, grasslands, pastures, fields, and waste places. It tends to prefer moist areas with full sun.

Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris)

This cute annual weed gets its name from its flat, triangular seed pods, which were thought to resemble the leather bags of food shepherds carried. It’s a member of the brassica family that’s native to Europe and parts of Asia but has naturalized in many areas, including North America. Today, shepherd’s purse is the world’s second most prolific wild plant.

Thankfully, like many other brassica family members, shepherd’s purse is a highly useful weed. It’s an excellent food crop and is cultivated in China, where it’s often stir-fried or added to wonton filling. Native Americans would grind the plant into a meal and make a drink with it. The leaves and flowers have a pleasant cabbage or broccoli-like flavor. When left to go to seed, the seeds develop a peppery flavor and were used as a pepper substitute in colonial New England.

Shepherd’s purse is also medicinal. Herbalists traditionally used its leaves to stop bleeding. You can use all of the plant’s aboveground parts to make teas and tinctures. Traditionally, herbalists used these preparations for circulation problems, mild heart failure, and other heart and blood complaints.

Look for shepherd’s purse growing in disturbed, open areas like gardens, pastures, roadsides, meadows, waste places, and farmland. It begins as a rosette of lobed leaves. Then it grows a stem 4 to 28 inches tall, topped by one or a few loose racemes of tiny, white, four-petaled flowers.

Speedwell (Veronica sp.)

There are over 500 species of speedwell, several of which are native to the United States. If you’re a flower gardener, you probably know the ornamental speedwell with its tall, spiky blooms. You may also recognize Persian or bird’s eye speedwell (Veronica persica) with tiny blue blooms that creeps into the cool, moist, loamy soil in gardens and lawns. While there is a large variation among the species, almost all of them share the same edible and medicinal characteristics.

Speedwell is edible in its entirety, but it tends to have a sharp, bitter flavor and is high in tannins. Historically, people have used it as a tea substitute during shortages and sparingly to add nutrition to meals.

Speedwell really shines as a medicinal herb. Internally, it may have some antibacterial, astringent, antiviral, and expectorant properties that can help treat coughs, colds, and flu. Herbalists also frequently use it externally in salves and washes, relying on some of these same properties to help treat skin infections, wounds, burns, and insect stings.

Generally, speedwell species thrive in open, sunny areas with cool, moist, loamy soil. You may spot it in pastures, gardens, parks, lawns, and waste places particularly in early spring when it puts on good growth during the cool, wet weather. A few species, like American speedwell (Veronica americana), are more selective about their habitat.

St. Johns Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

This plant is a must-learn herb for foragers and herbalists! Unlike other herbs, which you can order dried online, St. John’s wort must be used fresh. You can use the fresh leaves and flowers in salads and other dishes, but St. John’s wort is best known as a potent medicinal herb.

One of my favorite ways to use St. John’s wort is to make St. John’s wort oil, which is where the plant gets its name. During the Crusades, the Order of St. John used the oil to treat wounds on the battlefield. Modern studies have shown that it’s surprisingly helpful with pain, inflammation, and wound closure thanks to its antibiotic and anti-inflammatory properties. You can also tincture St. John’s Wort leaves and flowers. Herbalists sometimes use this tincture to treat anxiety and depression.

Thankfully, its five-petaled bright yellow flowers make it easy to pick out, and its Latin name hints at another key identifying feature of St. John’s Wort. The name perforatum refers to St. John’s wort’s leaves. If you hold one up to the light, you’ll notice that it looks like it’s perforated with tiny holes!

St. John’s wort tends to grow in coarse, well-drained, acidic, or neutral soils in open or disturbed areas. I frequently spot it on roadsides and in fields, but you can also find it growing in prairies, wetland margins, forest meadows, and areas affected by logging, forest fires, grazing, or road cuts.

Stinging Nettles (Urticia dioica)

Don’t be fooled; stinging nettles may be intimidating, but with a bit of know-how, they are a joy to find and eat. Stinging nettles are easily one of the best-tasting wild greens you can harvest! They’re highly nutritious and are loaded with vitamins C and A, calcium, potassium, magnesium, zinc, and iron. They’re also high in protein. You can eat the leaves, flowers, and seeds.

Sting nettles are also wonderful medicinal weeds. Herbalists often prescribe them for mothers. Nettle tea may increase breast milk production. People also use nettles to help treat allergies, arthritis, inflammation, and high blood pressure.

Another reason I love stinging nettle is that it tends to grow in dense patches, meaning it’s quick work to harvest a good mess. They have tall straight stems, occasionally reaching 8 feet tall. Their leaves are coarsely toothed, with pointed tips and heart-shaped bases. The leaves and stem feature tiny stinging hairs that give the plants their name.

Stinging nettles thrive in sunny, moist areas. Look for them along stream banks, lake edges, ditches, low pastures, damp waste areas, and woodland edges. I like to harvest nettles with gloves, but many foragers go without, using the calloused parts of their hands and fingers to pluck off the tips. Don’t worry about your mouth; the stinging hairs are easily removed by drying or blanching your nettles.

Thistle (Cirsium sp.)

There are about 200 species of thistle growing in the United States. Beautiful and dangerous, these thistles offer edible leaves, stalks, flower buds, and roots once you get past those big spikes. Thistles are medicinal, too. Herbalists often use the roots in internal and external preparations, and research has shown that they may help with bone health, liver issues, brain function, and more.

They’re easiest to spot in flower, and many people recognize their spiky pinkish or purple blooms. Unfortunately, many unsuspecting barefoot children find them in the grass long before they go to flower. Most thistles form a low-lying basal rosette of spiky leaves in their first year. While the spikes are certainly painful, they’re also a good identifying feature.

Thistles tend to grow best in open areas with moist soil. You’ll often find them in pastures, where livestock have picked around them. They also grow in grasslands, meadows, roadsides, tallgrass prairies, savannas, and forest edges.

Violets (Viola sp.)

These little beauties are one of the quintessential flowers of spring. Many people love looking at them, but few people realize that all of the viola species, including garden pansies and johnny jump-ups, are edible and medicinal. They’re one of my favorite spring weeds to collect because they have great flavor and are infinitely useful. You’ll find many old and new recipes for wild violets to put the flowers and leaves to good use, and my kids particularly love violet jelly.

Herbalists consider violas cooling and use them to create gentle herbal remedies like syrups, salves, infused oil, and vinegar. People often use violas internally to treat respiratory ailments like whooping cough and bronchitis. Externally, violas are excellent for soothing scraps, irritations, insect bites, eczema, and hemorrhoids. They may also help with varicose veins.

Violas thrive in consistently moist soil, so you’ll often find them in areas that offer at least partial shade, like woodland edges, small clearings, trailsides, streambanks, and seeps. Violas may also grow in lawns, gardens, and fields where the soil stays adequately moist.

Most viola species are low-growing heart-shaped leaves and flowers with five petals in a star formation, two petals pointing down and three pointing up. It’s a good idea to learn more about the viola species that grow around you or pick up a local wildflower field guide. Violas do have a few toxic lookalikes. Additionally, some native species of viola are rare and should be left to grow.

Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

Watercress is among the oldest known leafy vegetables consumed by humans! As its name suggests, it’s a water plant with hollow stems that allow it to float. Watercress is a perennial member of the brassica family with pinnately compound leaves and clusters of small white and green flowers. It resembles many other brassicas in appearance and flavor, which is slightly spicy, like mustard greens.

You can enjoy watercress sprouts, leaves, flowers, and seeds raw or cooked. They’re full of important vitamins and minerals like vitamins K, A, C, B6, riboflavin, calcium, and manganese. Just keep in mind that parasites like giardia and liver flukes can contaminate watercress. Many people choose to cultivate this awesome plant to avoid this issue.

Some studies have found that adding watercress to your diet may improve your immune system and help reduce your risk of diseases like cancer, osteoporosis, and heart disease. These benefits are due to the high levels of vitamins and antioxidants in the plant. Historically, herbalists have used watercress to treat a range of ailments, including constipation, inflammation, kidney problems, and arthritis.

Watercress thrive in cold, fast-moving water and often grow in streams and other freshwater habitats. However, you may also find it growing in ditches and along pond and marsh edges.

Wild Lettuce (Lactuca virosa)

Many herbalists refer to this helpful weed as the opium plant! When flowering, wild lettuce produces white sap with a compound lactucarium. This compound has analgesic, relaxant, and sedative properties that mimic those of opium. Before modern medicine and pain relief were widespread, wild lettuce was essential in the herbalist’s cabinet.

Wild lettuces are biennial plants related to the domesticated lettuce we grow in our garden. In their first season, they form a basal rosette of narrow-lobed or runcinate leaves. In the second season, wild lettuce sends up a flowering stem with clasping leaves. The flowers form a tightly packed cluster atop the stem.

Despite its infamous use in herbal medicine, wild lettuce is also a delicious, edible green. To harvest the greens, you want to find your wild lettuce in its first season and harvest the tender young leaves from the basal rosette. Certain species, like Canada wild lettuce (Latuca canadensis), have exceptionally tender, mild leaves. However, other species can be more bitter. If you find them to be too bitter, blanching the leaves will help.

Some wild lettuce species like woodland habitats, while others prefer open areas, and some tolerate drier soils, while others need a lot of moisture. In general, a few places you may find wild lettuce include small meadows, overgrown fields, trail sides, river bottoms, vacant lots, roadsides, and agricultural areas.

Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis)

This annual wildflower was brought to the United States sometime in the 18th century. Today, it’s widespread and commonly grows in disturbed areas like gardens, pastures, railroad tracks, and roadsides. It can be a nuisance in crop fields and is considered invasive in some states, thankfully it’s an easy one for foragers to make good use of.

Wild mustard forms a basal rosette of irregularly lobed, toothed leaves and a flower stem about 3 feet tall. Crush a leaf, and you’ll know why the plant gets its name—it gives off a strong mustard smell. The flowers are yellow with four petals and form a loose raceme at the top of the stalk.

You can eat the leaves, flowers, and seeds. The young leaves are okay in salads, but the older leaves tend to become hot and bitter. The flowers are good cooked and have a radish-like flavor. The seeds also have a spicy flavor, and in shortages, people have ground them as a substitute for true mustard. Some herbalists believe that wild mustard is good for treating a lack of appetite.

Wild Mint (Mentha sp.)