Affiliate disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our Privacy Policy.

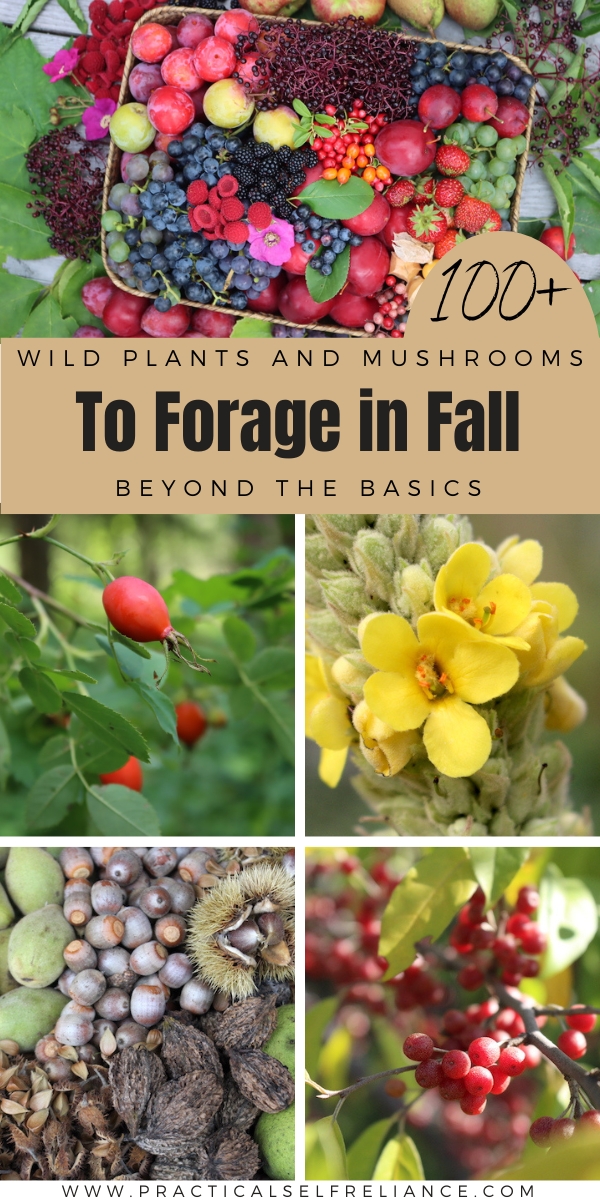

Fall foraging is some of the best you’ll see all year, and it seems like there’s abundance around every corner. No matter where you are, be it in the woods, open fields, or simply on your lawn, there’s something to find out there in the wild this season.

Welcome to the harvest season! Whether you’re brand new to foraging or are a seasoned wildcrafter, there’s something on this list for you.

Fall might be my favorite season for foraging. It’s a great time to be out in the woods and fields as the temperatures begin to cool off, bugs disappear, and the foliage starts to show off its brilliant colors. The long summer has also brought an abundance of food to the land that we can sneak out to gather before the cold of winter really sets in.

Nature is getting ready for winter, just like we are. Fall brings in some of the most calorie-dense wild foods you can find. It’s a great time to stock up on the nuts, roots, tubers, seeds, and grains that can bulk up your diet. The summer heat has also ripened the large, flavorful fruits you’ll find in autumn, like persimmons, apples, and pawpaws.

There’s more to fall than collecting nuts and picking apples, though. The cool season often brings renewed flushes of greens, mushrooms, and herbs. Gathering the season’s bounty can allow us to make flavorful, nourishing meals, craft potent herbal remedies, and stock the pantry.

I’ve designed this list to cover as many of fall’s wild foods as possible. You’ll find over 100 fruits, nuts, tubers, greens, herbs, mushrooms, and seeds that you can find in the forests, fields, lakeshores, ponds, and gardens near you this season.

I’ve included many of my favorite, common options for beginners, like lion’s mane mushrooms and blackberries, as well as a few lesser-known options for more advanced foragers, like saffron milk caps and nannyberries. There’s something for every forager to try.

Fall Foraging

There are so many wild foods available in the fall that I decided to break this list into sections for easier browsing. Some of these items are in multiple sections if they have different products. For example, curly dock is listed under ‘edible greens’, as well as ‘roots and tubers’ because you can harvest the plant for both during the fall.

Here’s how I have divided the list:

- Edible Greens

- Roots and Tubers

- Edible Trees

- Edible Seeds & Grains

- Wild Fruits and Nuts

- Pond, Bog, and Water Plants

- Fall Mushrooms

- Medicinal Plants

Exactly what you find near you will depend on your location and climate. Some species, like balsam fir, will only be found in a fairly limited range in the United States. Other species, like blackberries, have a more extensive range but ripen at different times. If you live in the southeast, your blackberry harvest may be finished at the end of July, while those foragers in the far north may still be picking them in early September.

Edible Greens

Spring is generally known as the season for edible wild greens, but fall can be a surprisingly abundant period. Many of the greens we forage in early spring thrive in cool, damp conditions. Not surprisingly, they sometimes put on a second flush of growth as we receive cool autumn temperatures and increased rainfall.

- Chickweed (Stellaria media)

- Curly Dock (Rumex crispus)

- Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

- Plantain (Plantago spp.)

- Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

- Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella)

- Foraging Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

- Violet Greens (Viola spp.)

- Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

- Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens)

- Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.)

Roots and Tubers

Autumn is the time for roots and tubers, and it’s not just because I love eating them roasted, baked, or boiled during the chilly months! It’s a great time to harvest because, during the fall, many perennial plants send energy into their roots and tubers as the aerial portion of the plant dies back for winter.

This time of year, they’re full of sugars, starches, and nutrients to help the plant survive the winter and send up foliage next spring. This process means they’re dense, nutritious, and flavorful for the humans and animals that seek them out.

Unfortunately, the plants dying back for fall can make them tricky to seek out and identify. It’s sometimes advisable to mark patches of choice plants earlier in the season. Use extra care when foraging for roots and tubers. Sadly, foragers and hikers have died after mistaking toxic species like Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum) for edible ones like Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota).

You should also keep in mind that harvesting the roots or tubers often kills the plant. While some, like Jerusalem Artichokes, thrive after a patch has been dug and divided, others, like cucumber root, are more sensitive and have faced overharvesting throughout much of their range.

- Burdock (Arctium lappa)

- Cucumber Root (Medeola virginiana)

- Curly Dock, Bitter Dock, etc. (Rumex spp.)

- Daylily Tubers (Hemerocallis spp.)

- Groundnuts/Hopniss (Apios americana)

- Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

- Jerusalem Artichokes (Helianthus tuberosus)

- Purple Yam (Dioscorea alata)

- Sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

- Sego Lily (Calochortus nuttallii)

- Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum spp.)

- Wild Carrots or Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

- Wild Onions (Allium spp.)

- Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

- Wild Potato (Orogenia linearifolia)

Edible Trees

Except for the major fruit and nut-producing trees like those listed below, trees are widely overlooked by modern foragers. In the past, these species provided many of our relatives with seasoning, vitamins, and survival food. Here are some edible trees, with tasty leaves, seeds, bark, or other products in the fall.

- American Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana)

- Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea)

- Birch (Betula spp.)

- Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

- Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

- Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- Kentucky Coffee Tree (Gymnocladus dioicus)

- Maple (Acer spp.)

- Pine (Pinus spp.)

- Slippery Elm (Ulmus rubra)

- Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

- Spruce (Picea spp.)

- Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata)

- Willow (Salix spp.)

Edible Seeds & Grains

In the not-so-distant past, our ancestors would have spent much of their late summer and fall harvesting, processing, and storing wild seeds and grains. Of the wild foods, these are easily some of the most calorie-dense items foragers could collect, so in ancient times, they were a major focus for many.

These wild grains are a far cry from the bleached all-purpose flour found on grocery store shelves. They’re nutrient-dense, mineral-rich, filling, and earthy. Thanks to modern industrial agriculture, all grains tend to get a terrible rap, but I find that these wild grains are worth exploring. In addition to their nutrition, they offer us a deep connection with the past.

- Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.)

- Barnyard Grass (Echinochloa spp.)

- Black Medic (Medicago lupulina)

- Crabgrass (Digitaria spp.)

- Crowfoot Grass (Dactyloctenium aegyptium)

- Dock Seeds (Rumex spp.)

- Indian Rice Grass (Achnatherum hymenoides)

- Lamb’s Quarters Seeds (Chenopodium album)

- Mallow (Malva sp.)

- Nettle Seeds (Urtica spp.)

- Plantain Seeds (Plantago spp.)

- Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

- Sunflower Seeds (Helianthus spp.)

- Wild Rice (Zizania spp.)

- Wild Rye (Elymus spp.)

Wild Fruit

Fruit is generally in abundance in autumn. In many areas, we’re still harvesting small fruit like raspberries, and larger fruit like crabapples have finally begun to ripen after the warm summer season. Wild fruit is one of my favorite categories to forage because it’s loaded with vitamins and flavor.

It’s also fun for the kids because most of it is relatively easy to identify and can be eaten immediately. Wild fruit is also generally easy to preserve through drying, canning, or freezing and can help provide wholesome, vitamin-rich meals through the winter months, just like it did for our ancestors.

- American Persimmons (Diospyros virginiana)

- Apples (Malus spp.)

- Autumn Olives (Elaeagnus umbellata)

- Barberries (Berberis spp.)

- Blackberries (Rubus spp.)

- Blueberries (Vaccinium spp.)

- Chokecherries (Prunus virginiana)

- Chokeberries (Aronia spp.)

- Cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon)

- Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

- Grapes (Vitis spp.)

- Hawthorn Berries (Crataegus spp.)

- Juniper Berries (Juniperus spp.)

- Nannyberries (Viburnum lentago)

- Pawpaws (Asimina triloba)

- Raspberries (Rubus spp.)

- Rosehips (Rosa spp.)

- Rowan Berries (Sorbus aucuparia)

- Sloes (Prunus spinosa)

- Staghorn Sumac Berries (Rhus typhina)

- Wild Plums (Prunus americana)

- Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides)

Wild Nuts

Most nuts take a long time to ripen, so generally, we’re only able to harvest them during the fall. If you’re trying to incorporate more wild food into your diet, nuts are a great option. They’re generally fairly easy to harvest, and you can pick up most of them off the ground.

Compared to other foraged foods, these items are packed with calories, protein, and healthy fat. Even if you still get most of your calories from the grocery store, harvesting some wild nuts may be worth it. Grocery store nuts have high price tags and lackluster flavor compared with the species you’ll find in your local woodlands.

- Acorns (Quercus spp.)

- Beachnuts (Fagus spp.)

- Butternuts (Juglans cinerea)

- Chestnuts (Castanea spp.)

- Hazelnuts (Corylus spp.)

- Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.)

- Pecans (Carya illinoinensis)

- Pine Nuts (Pinus spp.)

- Walnuts (Juglans spp.)

Pond, Bog, and Water Plants

Fall isn’t necessarily my favorite time of year to play in the water, but it is a good time to go after certain water plants. Many water plants produce tasty tubers, and as I discussed in the root and tuber section above, autumn is a great time to harvest them, as they’re most palatable and nutritious.

- Arrowhead or Duck Potato (Sagittaria latifolia)

- Cattail Roots (Typha spp.)

- Sweet Flag (Acorus calamus)

Fall Mushrooms

While you’re out in the woods picking berries and gathering nuts, watch mushrooms! Fall is an excellent time to find a few amazing mushroom species. Some of these species flush in only in autumn, while others are seen in spring and sometimes again in the fall as the temperature dips and rainfall levels increase.

I decided to divide the mushrooms further into sections based on the knowledge and experience needed to safely and correctly identify, harvest, and prepare them. The first section is suitable for beginners, with easy-to-pick-out mushrooms like black trumpets that offer no toxic lookalikes.

The second section is mushrooms that I feel are best suited for intermediate foragers. These mushrooms are still pretty easy to identify and generally straightforward to prepare. They may have a few lookalikes, but with a guidebook and some basic knowledge, you should be able to identify them positively.

The last section on this list includes mushrooms suitable only for advanced foragers. These may be exceptionally tricky to identify, difficult to prepare properly, and/ or have deadly toxic lookalikes. It’s fine to attempt to identify these mushrooms and appreciate their natural beauty, but you should only use them if you are 100% confident in your ability or are supervised by an expert.

Many of the mushrooms on this list are delicious culinary mushrooms prized by chefs and home cooks alike for their unique, wonderful flavors. Others, like the turkey tail mushrooms, are solely for medicinal use. Some mushrooms, like lion’s mane, are both tasty and medicinal. Learning the best way to use each of these species is key to having the best foraging experience.

Beginner Foragers

- Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus cornucopioides)

- Cauliflower Mushrooms (Sparassis spp.)

- Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus)

- Hedgehog Mushrooms (Hydnum repandum)

- Hen of the Woods or Maitake (Grifola frondosa)

- King Boletes (Boletus edulis)

- Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus)

- Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.)

- Shaggy Mane Mushrooms (Coprinus comatus)

- Witches Butter (Tremella mesenterica)

Intermediate Foragers

- Dryad’s Saddle or Pheasant Back (Cerioporus squamosus)

- Lobster Mushrooms (Hypomyces lactifluorum)

- Puffball Mushrooms (Calvatia spp.)

- Saffron Milk Caps (Lactarius deliciosus)

- Turkey Tail Mushrooms (Trametes veriscolor)

- Winecap or King Stropharia (Stropharia rugosoannulata)

- Yellowfoot Chanterelles (Craterellus tubaeformis)

Advanced Foragers

- Coral Mushrooms (Ramaria spp. and Artomyces spp.)

- Honey Mushrooms (Armillaria spp.)

- Indigo Milk Cap (Lactarius indigo)

- Matsutake (Tricholoma matsutake)

- Shrimp of the Woods (Entoloma abortivum)

- Velvet Foot Mushrooms or Enoki (Flammulina velutipes)

- Wood Blewits (Collybia nuda)

Medicinal Plants

Fall is a good time to collect many medicinal plants, especially those we harvest for their roots. While some of the plants listed in other sections may have some medicinal properties, we primarily see them in a culinary setting. These herbs, on the other hand, are almost always used in herbal remedies. They may not be the best-tasting items to forage on this list, but they’re great for making potent, natural medicine. You can use many of these herbs to create healing tinctures, teas, salves, and more.

- Angelica Root (Angelica sinensis)

- Chicory Root (Cichorium intybus)

- Dandelion Root (Taraxacum spp.)

- Echinacea Root (Echinacea spp.)

- Goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

- Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium fistulosum)

- Mallow Root (Malva neglecta)

- Marshmallow Root (Althea officinalis)

- Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca)

- Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris)

- Mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

- Stinging Nettles (Urtica dioica)

- Teasel Root (Dipsacus fullonum)

- Wild Lettuce (Lactuca spp.)

- Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

Foraging Lists

Looking for more lists of wild edible plants to fuel your foraging passion?

- 13+ Edible Wild Mushrooms for Beginners

- 20+ Edible Weeds in Your Garden

- 60+ Edible Wild Fruits and Berries